The Sun will eventually kill all complex life on Earth. Not tomorrow—but in roughly one billion years. Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere will collapse, suffocating every organism needing oxygen.

Scientists have recently published a study that narrows this timeline far beyond old textbook estimates.

They used 400,000 computer simulations to predict when our planet will no longer support complex life. The research reveals Earth operates on a strict deadline—one that arrives sooner than we thought.

The Surprise Revision

For decades, textbooks have stated that the Earth could support complex life for roughly two billion years. That comfortable estimate shaped how scientists think about distant planets.

But researchers from Toho University and Georgia Tech recalculated. Their new answer: one billion years, plus or minus 140 million.

This half-billion-year cut matters. It rewrites what we know about atmospheric stability, life’s fragility, and what we should search for on distant worlds.

Why Models Change

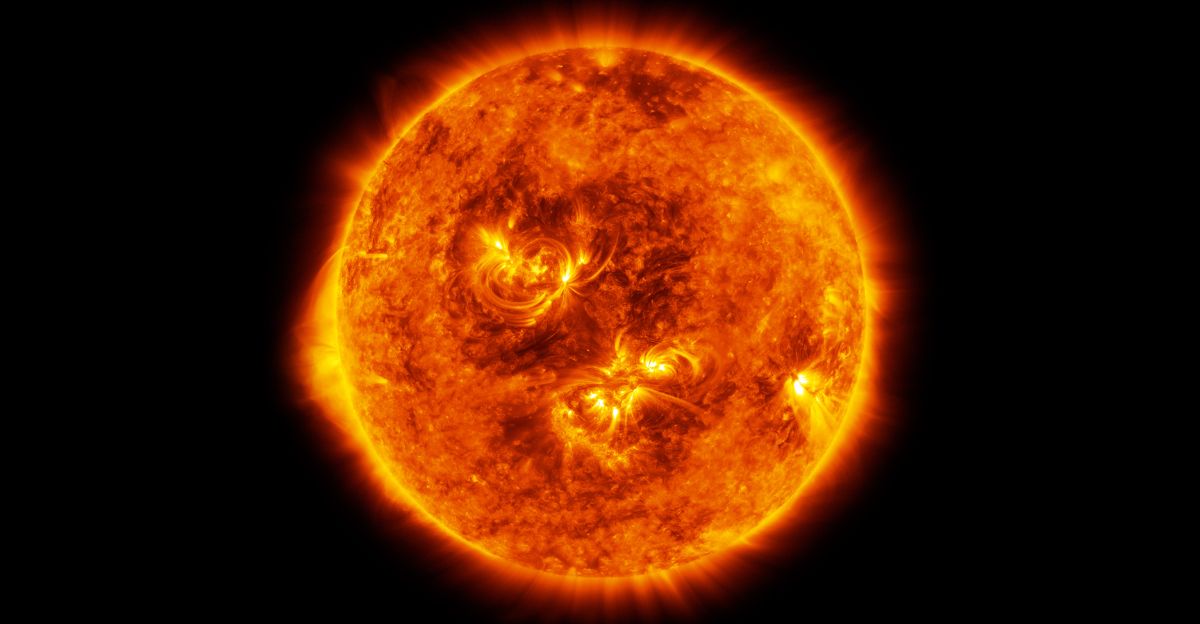

The old two-billion-year estimate wasn’t wrong—it was incomplete. Scientists knew the Sun brightens over time as nuclear fusion continues in its core. Rising solar brightness warms Earth, raising temperatures.

However, earlier models overlooked a crucial feedback loop: rising temperatures cause more water to evaporate. Water vapor traps more heat, thereby accelerating the warming process further.

The new study uses “stochastic modeling”—running simulations thousands of times with different variables. This probabilistic method catches the dynamics that single simulations miss.

The Mechanism Explained

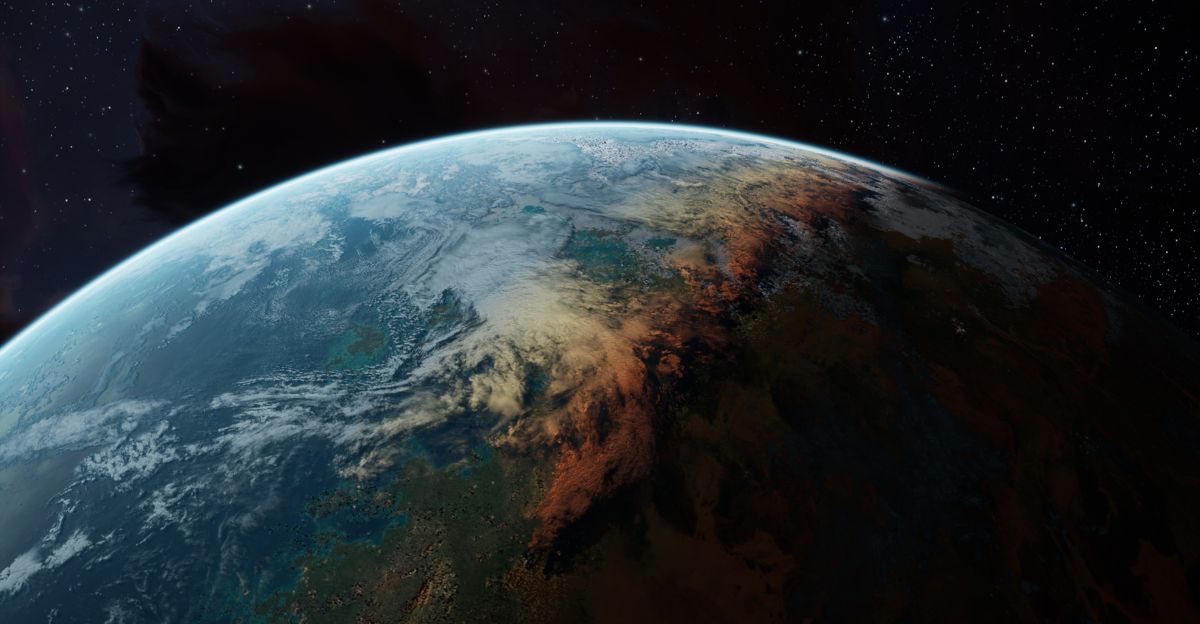

Here’s why the new timeline is shorter: warming breaks down atmospheric carbon dioxide under ultraviolet radiation. Simultaneously, heat causes oceans to evaporate more, thickening the greenhouse effect.

Plants die when CO₂ drops below survival thresholds. Without plants producing oxygen, oxygen levels plummet. Ocean algae also fail as waters warm and stratify.

Once oxygen starts declining, feedback loops accelerate the collapse. Within 10,000 years—geologically speaking, an instant—oxygen levels crash from 21 percent to just one percent.

The Central Finding

The Ozaki-Reinhard study pinpoints Earth’s timeline with unprecedented precision: the oxygen-rich atmosphere lasted approximately 1.08 billion years, with an uncertainty of ±140 million years.

After this threshold, “rapid deoxygenation” occurs. This represents the best current forecast for when Earth shifts from “complex life habitable” to “microbes only habitable.”

Scientists defined “oxygen-rich” as atmospheric O₂ above one percent of today’s levels. Climate models and stellar physics confirm that this timeline aligns with the point at which surface temperatures become too hot for multicellular organisms.

A Cascade of Extinctions

Complex life won’t vanish instantly—it will disappear in waves. C₃ plants (the most common) fail first, around 100 million years from now, when CO₂ levels drop too low.

Large animals follow, unable to handle extreme heat and humidity. Models show multicellular life went extinct around 800 million years ago.

Eukaryotes (cells that make all animals, plants, and fungi) vanished around 1.3 billion years ago. Only extreme heat-lovers—bacteria and archaea—survive in the deep Earth. Eventually, they even surrender.

Why Today’s Warming Matters

Some ask: if Earth dies in a billion years anyway, why fight climate change now? The answer shows why this research remains urgent.

The same models predicting Earth’s distant death also show how sensitive our climate is to small changes. Human CO₂ emissions accelerate warming, which triggers an oxygen collapse.

Solar physics will eventually doom us, but humans are accelerating the loss of habitability within centuries. We’re shortening the window when civilization thrives. Every degree of warming matters.

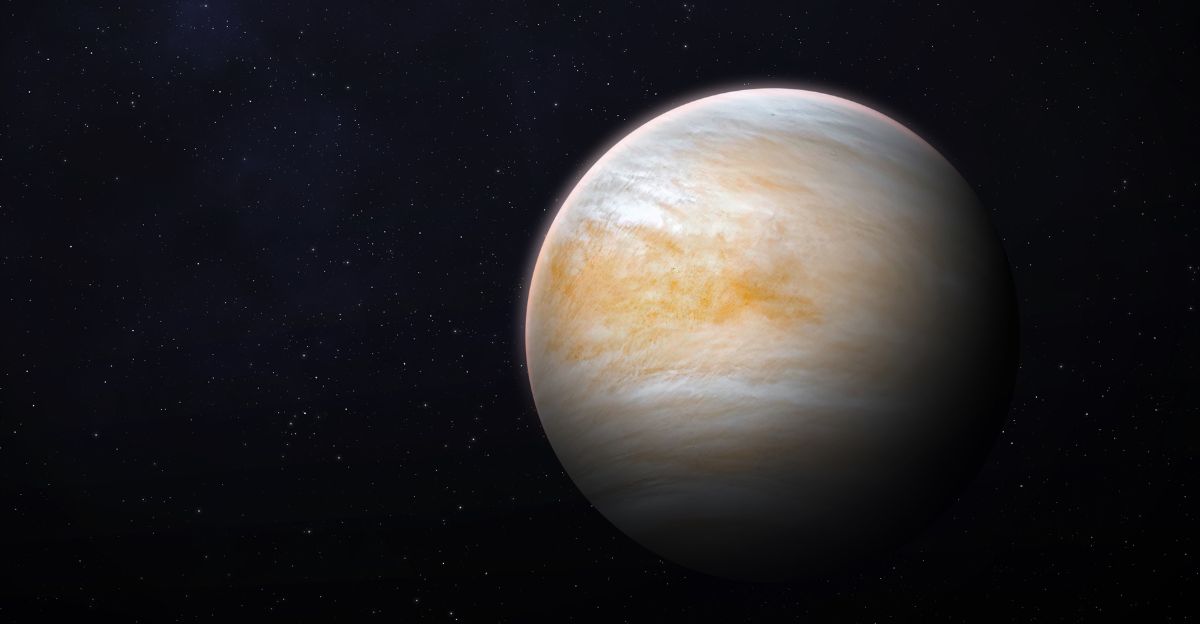

Venus: A Cautionary Tale

Scientists study Venus to gain insight into Earth’s future. Venus was once potentially habitable with liquid water and a thin atmosphere. It underwent a runaway greenhouse effect between 250 million and three billion years ago.

Today, Venus reaches a temperature of 475 degrees Celsius (hot enough to melt lead) with an atmosphere 92 times thicker than Earth’s, primarily composed of carbon dioxide.

Planetary scientists believe that Venus experienced exactly the same fate as Earth: solar brightening triggered water loss, greenhouse feedback, and runaway change. Earth follows the same path, albeit at a slower pace.

The Scientific Consensus Shifts

The Ozaki-Reinhard findings don’t stand alone. Multiple studies converge on similar timelines. A 2013 University of East Anglia study estimated a range of 1.75 to 3.25 billion years. Wolf and Toon (2014) suggested 1.5 billion years.

Earlier work cited “two billion years” as standard. The 2021 refinement to one billion years shows consensus tightening—not reversal, but narrowing toward lower estimates.

Better climate modeling, improved understanding of stellar evolution, and refined biogeochemistry calculations drive this shift. Mainstream science now supports this timeline.

The Oxygen Cliff

Here’s the critical insight: atmospheric oxygen won’t fade slowly. Models predict rapid collapse around the billion-year mark.

Oxygen remains stable for hundreds of millions of years, then drops from present levels to one percent within 10,000 to 100,000 years—a geological instant. This “rapid deoxygenation” occurs because feedback loops accelerate exponentially.

Complex life faces a sudden cliff edge, not a gradual decline. This changes exoplanet thinking. A planet might appear habitable yet sit on oxygen collapse’s edge—happening far faster than climate change alone.

Solar Brightening: The Driver

All timelines trace to one fact: the Sun grows brighter. Every 100 million years, solar luminosity increases one percent as hydrogen fuses to helium. Modest seeming—but over a billion years, compounds into transformative change.

Earth’s past proves this: the Sun has brightened roughly ten percent since life emerged 3.8 billion years ago. As solar output rises, Earth receives more radiation.

Temperatures climb. Water vapor feedback amplifies this warming. Paradoxically, CO₂ becomes limiting—it breaks down under ultraviolet radiation. Photosynthetic life cannot persist without it.

Water’s Double Edge

Water enables all life, yet becomes life’s executioner. As temperatures rise, the oceans evaporate more quickly.

Water vapor rises into the upper atmosphere, where ultraviolet radiation breaks it apart in a process called photolysis. Hydrogen—the lightest element—escapes into space. Oxygen atoms remain but cannot reform water molecules without hydrogen.

This process dries the Earth over millions of years. Once oceans vanish, complex water-dependent life cannot recover. The process becomes irreversible on biological timescales. The Sun steals Earth’s water, molecule by molecule.

A Window for Detection

This discovery changes exoplanet research strategy. If Earth-like planets maintain oxygen-rich atmospheres for only one billion years—roughly 20-30 percent of their total habitable lifetimes—then oxygen becomes a rare biosignature.

An oxygen-rich atmosphere signals the possibility of life, but it doesn’t last. This reshapes how scientists search for alien life.

Exoplanet surveys show snapshots in time; they cannot reveal whether a world is early in its habitable phase or approaching collapse. Future telescopes should prioritize young systems or planets orbiting stable, long-lived stars.

The Extremophile Endgame

Life as we know it may come to an end, but life itself might not. Extremophile microorganisms—heat-loving and radiation-resistant—could theoretically survive in subsurface environments even after surface conditions become hostile.

The deep Earth crust hosts geothermal energy and serves as a radiation shield. Primitive life might persist for another billion years or longer.

“Deep biosphere” organisms already thrive in Earth’s crust today, surviving in conditions that would instantly kill surface life. Models suggest that prokaryotic life persists until surface temperatures reach 422 Kelvin (149°C) everywhere, roughly 2.8 billion years from now.

Implications for Climate Action

This research might justify inaction—if Earth dies in a billion years anyway, ignore climate change now? Wrong. The Ozaki-Reinhard timeline describes an unavoidable future driven by stellar physics.

Human emissions don’t alter this endpoint, but they compress the timeline for civilizational decline. We must decide how much of the remaining billion years will support human society comfortably.

Every fraction of warming narrows the window for technological development and agricultural stability. Climate action isn’t “saving the planet”—Earth recovers after we’re gone. It’s preserving human flourishing conditions.

New Research Directions

Since 2021, planetary scientists have refined specific components of their models. Recent work examines atmospheric chemistry during oxygen loss, testing whether transitions become even more abrupt than predicted.

Some researchers investigate whether microbial life persists in cloud layers or polar regions longer than models suggest. Others develop methods to detect “dead biospheres”—planets that have lost their habitability—by searching for chemical signatures of past life in their atmospheres and geology.

Scientists explore whether non-biological processes replenish oxygen, although evidence suggests that no natural mechanism can restore it. These studies strengthen, not overturn, the main findings.

Detection Challenges and Methods

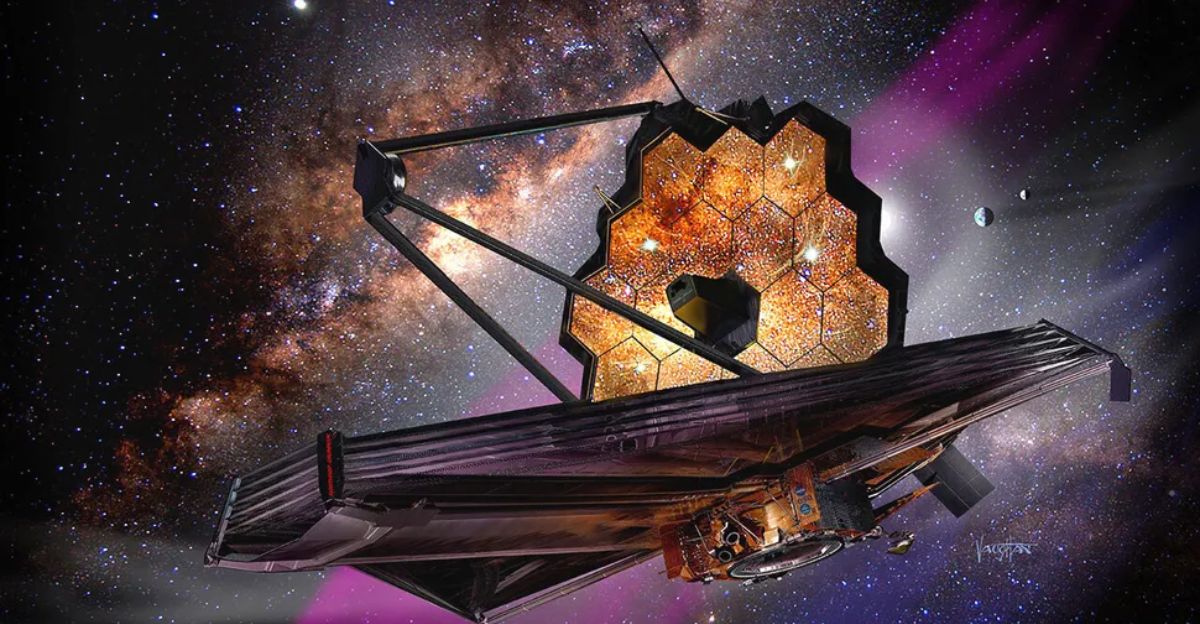

Observing oxygen on distant exoplanets requires advanced spectroscopy. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) detects atmospheric gases by analyzing how starlight filters through exoplanet atmospheres.

However, JWST cannot yet reliably distinguish biological oxygen from non-biological sources. Future missions, such as the Habitable Worlds Observatory (planned for the 2040s), aim for greater sensitivity.

Even discovering an oxygen-rich exoplanet creates challenges: scientists cannot determine whether it’s in early flourishing or rapid decline phases without additional data. Researchers develop methods cross-correlating oxygen with methane and atmospheric dynamics to constrain a planet’s biological age.

Public Perception and Misunderstanding

The headline “Earth’s Expiration Date” prompted social media anxiety and sensationalist misinterpretation. Some outlets compressed a billion-year timeline into language suggesting imminent crisis.

Fact-checkers clarified: no immediate threat exists from this mechanism. Others dismiss the research as irrelevant because the timeline seems distant. Both reactions miss the mark. The research neither demands panic nor permits ignoring climate change.

A responsible reading acknowledges the mechanism’s certainty (real physics) while maintaining perspective (incomprehensibly long by human standards). Scientists stress this research illuminates climate sensitivity and exoplanet habitability—not tomorrow’s weather.

Echoes of Past Predictions

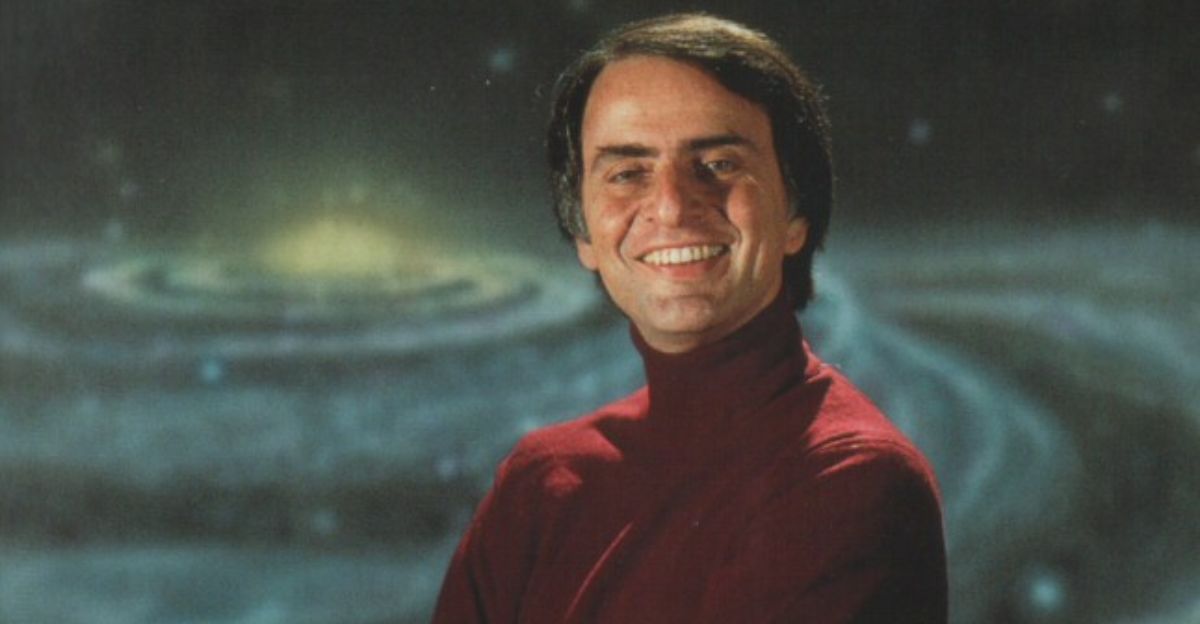

Scientists have long studied the habitability of Earth. In the 1970s and 1980s, Carl Sagan and Michael Hart estimated the remaining habitability at roughly 500 million to 2 billion years using available models.

These estimates were reasonable given their data, but they lacked the computational power and refined climate models available today.

Earlier, 19th-century physicist Lord Kelvin calculated Earth’s age from cooling rates and concluded it was merely tens of millions of years old—wildly wrong.

Scientific estimates improve with better tools and data, not contradiction. The Ozaki-Reinhard study exemplifies this progression: greater computing, detailed modeling, and accurate constants. Future research will refine timelines further.

The Bottom Line

Earth has approximately one billion years of habitability remaining—a number that feels simultaneously impossibly vast and strikingly concrete.

It’s long enough that no human concern should pivot on this timeline. It’s concise enough to reshape our perspective on life, planets, and stewardship.

The research yields three key takeaways: First, the Sun’s gradual brightening will inevitably render Earth uninhabitable through a runaway greenhouse effect—not a theory, but a physical phenomenon.

Second, timelines narrowed from vague estimates to scientifically justified numbers. Third, understanding this process sheds light on climate sensitivity and biosphere fragility everywhere. We’re not facing imminent threats from the stars. We are custodians of Earth’s habitable future.

Sources:

- Nature Geoscience (2021)

- EurekAlert, March 1, 2021

- ArXiv 2103.02694

- Ozaki & Reinhard

- Carl Sagan & Michael Hart’s historical work

- Science journalism outlets (2025)