A vast, volatile blemish on the sun has rotated into direct view of Earth, drawing close scrutiny from space weather agencies. The active region, a massive sunspot complex tracked by NASA and NOAA, is the largest seen in about a decade and large enough to raise questions about how prepared modern infrastructure is for an extreme solar storm.

Sunspot nearly rivaling the 1859 benchmark

Spanning roughly 180,000 kilometers, the complex is wider than Earth and large enough to contain several Earth-sized worlds within its darkest cores. Observers compare its scale to the famous 1859 “Carrington Event,” with estimates suggesting the current formation is about 90 percent as large as the sunspot that preceded that historic storm. The Carrington Event remains the baseline for a worst-case solar storm: it briefly turned night skies bright and disrupted telegraph systems across continents at a time when electrical networks were in their infancy.

By contrast, today’s societies depend on densely interconnected power grids, navigation systems, and global communications. That contrast is what makes a sunspot of this size noteworthy. While its presence alone does not guarantee a major storm, it greatly increases the potential for powerful solar eruptions that could affect Earth if aimed in our direction.

A persistent “zombie” region returns

The region now designated AR 4299 is not a new arrival. It first crossed the Earth-facing side of the sun earlier in the current solar rotation as AR 4274, producing bright auroras before it disappeared over the limb to the far side. Many such active regions decay as they travel around the star, but this one persisted.

After completing a roughly 27-day circuit, the complex re-emerged on the visible disk larger, darker, and more magnetically intricate than before. That resilience has led some scientists and observers to describe it informally as a “zombie” sunspot that refused to dissipate as expected.

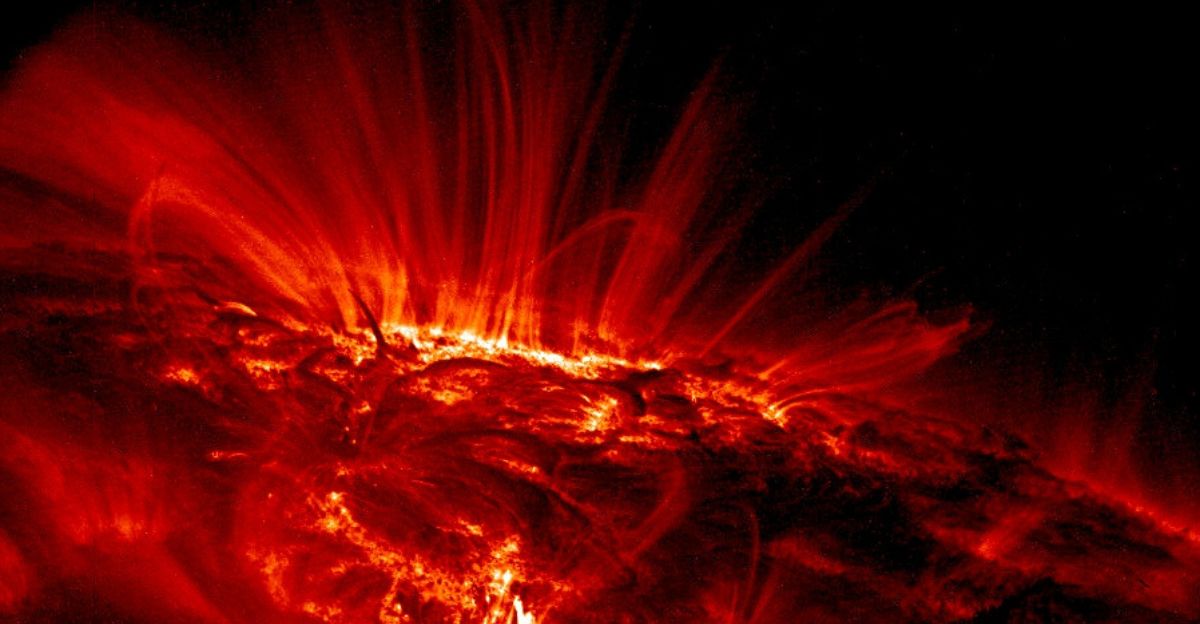

Sunspots mark zones where magnetic fields are strongly concentrated and tangled. These knots can store enormous amounts of energy; when field lines snap and reconnect, they can release bursts of radiation called solar flares and sometimes launch Coronal Mass Ejections, or CMEs—huge clouds of charged particles that can cross space and interact with Earth’s magnetic field.

Watching the firing line

At present, NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center reports that no major CMEs from this specific complex have struck Earth. For now, the effect has been mostly visual, offering striking views through properly filtered telescopes and generating heightened interest among professional and amateur solar observers.

The geometry is changing, however, as the sun slowly turns. Over the next several days, the rotation will carry AR 4299 into a central, more “geoeffective” position where any strong CME it produces would have a clearer path toward Earth. Forecast centers are monitoring its magnetic configuration in detail, looking for signs that the region is becoming more likely to produce powerful flares.

Space weather prediction remains an inexact science. Experts can identify unstable regions and track flares as they occur, but they cannot reliably forecast the precise timing or direction of the most extreme eruptions. The result is a waiting period in which the likelihood of an Earth-directed event is elevated, but the outcome is uncertain.

Vulnerable systems: from orbit to the grid

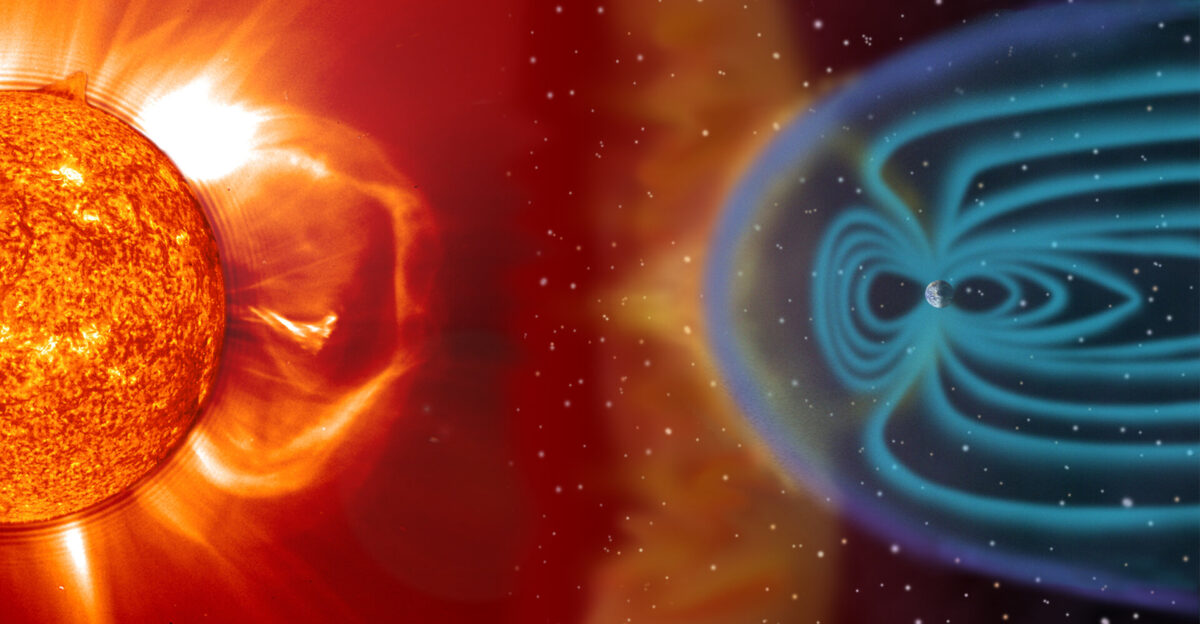

If AR 4299 unleashes a major flare and accompanying CME toward Earth, the first impacts would likely be felt in space. There are now on the order of ten thousand or more active satellites in orbit, including large constellations that provide broadband connectivity. During strong geomagnetic storms, Earth’s upper atmosphere can heat and expand, increasing drag on low-orbiting spacecraft and potentially altering their paths. High-energy particles and induced currents can interfere with onboard electronics and sensors.

Disruptions could cascade to users on the ground. Navigation signals from GPS and similar systems are particularly sensitive to disturbances in the ionosphere, the charged upper layer of Earth’s atmosphere. A severe storm can degrade positioning accuracy or temporarily interrupt signals over large areas. That would affect everything from personal navigation devices to aviation, shipping, and emergency services, all of which rely on precise timing and location data.

Researchers have also highlighted the sensitivity of undersea communication infrastructure. Studies led by experts such as Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi indicate that long submarine cables and their repeaters may be at increased risk in severe geomagnetic events, especially in higher-latitude regions. In an extreme case, damage or outages in key links could cause regional or even multi-continental connectivity problems, isolating parts of the world from the broader network.

On land, the greatest concern is for high-voltage power grids. A strong geomagnetic storm can induce electrical currents in the ground that enter transmission lines and transformers. If those induced currents are strong enough, they can overheat and damage large transformers that are difficult and time-consuming to replace. Risk assessments of a modern analog to the Carrington Event have produced projected economic costs ranging from hundreds of billions to several trillion dollars, factoring in prolonged outages, supply chain disruptions, and broader economic slowdown.

Preparedness and the solar cycle

Despite these risks, Earth is not without defenses. Agencies such as NASA and NOAA operate a suite of solar observatories and space-based monitors that provide continuous views of the sun and near-Earth space. When a major CME is observed heading toward Earth, instruments located between the sun and Earth can sample the incoming cloud, giving forecasters a lead time of roughly 15 to 72 hours before the disturbance fully impacts the planet’s magnetic field.

That window is critical. Grid operators can temporarily adjust power flows, take vulnerable equipment offline, or reconfigure networks to reduce stress on key components. Satellite operators can switch spacecraft into safer modes, limit certain operations, or adjust orbits to mitigate atmospheric drag. Aviation routes over polar regions, where radiation exposure and communication disruptions can be greater, can also be altered if needed.

The emergence of AR 4299 coincides with the peak of the sun’s approximately 11-year activity cycle, known as solar maximum. During this phase, large sunspots and solar eruptions become more frequent. What is unusual now is not that such a region exists, but that human societies are more technologically dependent and interconnected than during previous cycles, making the potential impact of a rare, extreme storm much higher.

In the coming days, the sun’s rotation will gradually move the sunspot complex out of its most threatening alignment with Earth. If it remains relatively quiet during that interval, the immediate risk will diminish as the region drifts toward the solar limb and eventually out of view. Regardless of the outcome, the event underscores the need for continued monitoring, improved forecasting, and resilience planning as the current solar maximum unfolds.

Sources

NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Space Weather Story of the Week, December 1–5, 2025 (spaceweather.gov)

NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory – Active Region AR 4294–4298 imagery and analysis, December 2025 (nasa.gov)

Newsweek – “Biggest Sunspot in Decade Could Bring Giant Solar Flare, Bright Auroras,” December 1, 2025

Forbes – “Giant New Sunspot And X-Class Solar Flare Could Bring Bright Auroras,” December 1, 2025

PC World – “NASA spots huge sunspot complex facing Earth. What that means for us,” December 3, 2025