Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier, often called the “Doomsday Glacier,” is moving into a more unstable phase that could reshape shorelines around the world. Roughly the size of Florida, it is already responsible for about 4% of current global sea-level rise and is shedding an estimated 50 billion tons of ice each year. If it fails completely, scientists warn it could destabilize the wider West Antarctic Ice Sheet, driving sea levels 10 to 11 feet higher and overwhelming defenses in many coastal regions.

Why the Glacier Is Rapidly Weakening

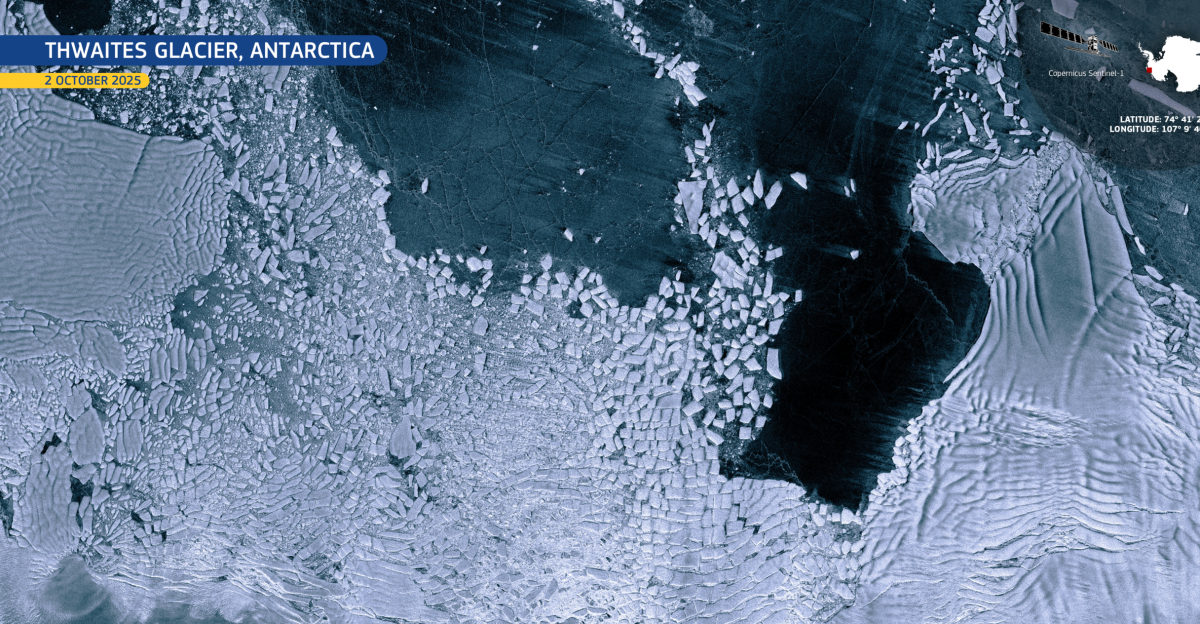

Researchers now trace much of Thwaites’ deterioration to powerful currents beneath the ice, sometimes described as underwater storms. These swirling flows form where relatively warm and cold waters meet, then surge toward Antarctica and eat away at the glacier’s base. High‑resolution satellite radar collected between March and June 2023 reveals that warm seawater is pushing miles inland under the ice, repeatedly shifting the so‑called grounding zone where the glacier meets the seabed.

Each tidal cycle lifts the ice slightly and allows more water to surge in and out, steadily weakening the key “buttress” that helps hold Thwaites in place. The result is a faster retreat and thinning from below, in ways that conventional sea‑level projections have not fully captured.

Hidden Tides and a Critical “Blind Spot”

The new analysis exposes a large gap in existing computer models. The grounding zone of Thwaites can migrate several kilometers over just 12 hours as tides rise and fall, far more movement than many simulations assume. As the tide pushes warm water inland, the glacier is effectively jacked up by centimeters at a time, opening space for more ocean water to circulate beneath it and increasing melt.

This constant flexing adds stress at the base of the ice and speeds its retreat. Scientists now worry that the glacier may be closer to an irreversible tipping point than previously believed, where relatively small increases in ocean heat could trigger much larger, self‑sustaining ice loss. Glaciologist Christine Dow has noted that what was once thought to be a 100‑ to 500‑year process may unfold “much faster than that,” compressing timelines for preparation.

The Cork Holding Back West Antarctica

On its own, a full collapse of Thwaites could raise global sea levels by more than two feet. Its larger importance, however, lies in its role as a stopper for the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a basin of marine ice nearly three times the size of Texas. Thwaites helps hold back this deeper inland ice; if it fails, the rest of the basin could begin to flow more freely into the ocean.

In that scenario, long‑term sea‑level rise of about 10 to 11 feet becomes possible. Such an increase would redraw coastlines on every continent, submerging low‑lying districts, eroding protective wetlands, and driving saltwater farther into river deltas and groundwater supplies. Even if the full rise unfolded over centuries, the momentum of a destabilized ice sheet would keep oceans rising far beyond any near‑term peak in greenhouse gas emissions.

Coastal Cities, Property, and Financial Strain

In the United States alone, roughly 127 million people live in shoreline counties that would face higher flood risk as Antarctic melt accelerates. Major metropolitan areas such as New York, Miami, Boston, New Orleans, and San Francisco are already confronting more frequent high‑tide flooding, and a multi‑foot rise would threaten transport systems, power networks, and port facilities.

Economic exposure is substantial. Estimates suggest that a 10‑foot increase in sea level would place on the order of $1 to $2 trillion in coastal property at risk nationwide, once homes, commercial buildings, and critical infrastructure are included. Earlier work by the Union of Concerned Scientists put 2.5 million particularly vulnerable U.S. homes at about $1.07 trillion in value, and broader tallies that factor in roads, utilities, and industrial sites significantly raise the total.

For households in low‑lying areas, chronic flooding is already driving up insurance premiums and repair bills. Insurers and mortgage lenders in states such as Florida and California are re‑evaluating risk, which can translate into higher borrowing costs or reduced access to coverage, particularly for lower‑income residents with fewer options to move. At the same time, companies that build flood‑resilient structures, provide climate‑risk analytics, or develop adaptation technology may see growing demand.

Adaptation Efforts and Geoengineering Debates

Some developers and utilities are beginning to treat Antarctic‑driven sea‑level scenarios as a central planning factor. In certain regions, new buildings are being elevated, substations and data centers are shifted inland, and long‑lived coastal projects are delayed while uncertainties around Thwaites are reassessed. Yet many zoning codes and federal or local models still rely on projections that may underestimate potential rates of rise if widespread seawater intrusion beneath Antarctic ice is confirmed.

In parallel, scientists are debating whether direct intervention could slow Thwaites’ decline. Research groups describe a 15‑ to 30‑year window to determine if experimental approaches are feasible. Ideas under discussion include flexible underwater curtains or bubble barriers designed to block warm deep water from reaching the glacier’s base, and artificial structures on the seabed to add drag and slow ice flow. Critics point to immense engineering challenges, unknown ecological effects, and governance questions in one of Earth’s most fragile and least disturbed regions.

From orbit, satellite instruments now track subtle shifts in Thwaites’ surface and the invisible ocean heat below, painting a picture of a glacier in what some researchers characterize as a lasting regime shift. That raises difficult choices for coastal communities: how to balance near‑term investments in defenses such as seawalls and wetlands restoration against longer‑term strategies like managed relocation.

Even if a complete collapse of Thwaites and West Antarctica ultimately takes centuries, present‑day decisions on emissions, land use, and infrastructure will shape how manageable that transition is. Rapid cuts in greenhouse gases would not stop sea‑level rise already locked in, but they could slow the rate of change, buying time for cities and towns to adapt. As the “dam” of West Antarctica shows increasing signs of strain, planners and residents alike face the prospect that maps passed down to future generations may look markedly different from the coastlines we know today.

Sources:

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

UC Irvine / PNAS May 2024 Thwaites study

IPCC AR6 Physical Science Basis

CNN / BBC archives

British Antarctic Survey

NOAA Sea Level Rise Technical Report

Union of Concerned Scientists 2018 analysis