Nothing can quite excite the world like a discovery that changes the way we think about the past and everything we thought we knew to be true. The discovery of 22,000-year-old human footprints in New Mexico offers a tangible window into humanity’s distant past. Before this breakthrough, mainstream theories held that humans first arrived in the Americas about 13,000–16,000 years ago, following the melting of vast ice sheets.

However, radiocarbon dating on seeds and sediments has confirmed that humans were present several millennia earlier than we once thought.

Where The Discovery Was Made

These remarkable footprints were discovered in White Sands National Park, located within the Tularosa Basin of southern New Mexico. This region’s striking landscape is dominated by gypsum sand dunes, the largest such field in the world, sitting near the site of the ancient Lake Otero. Tens of thousands of years ago, during the ice age, Lake Otero covered approximately 1,600 square miles, which is almost the complete opposite of what it is today.

The first discoveries at White Sands emerged in 2009 when scientists noticed unusual dark spots along the lakebed. These spots were later excavated to reveal human and megafaunal footprints.

The Remarkable Footprints

More than sixty distinct human tracks are preserved in the ancient mud beds that once lined the shores of Lake Otero. These prints are distributed across seven stratigraphic layers, indicating repeated periods of occupation over roughly 2,000 years in the late Ice Age.

Most of these prints are flatter-footed and smaller, especially compared to typical adults, suggesting that teenagers and children were predominant in these preliminary communities.

Earlier Chronologies and Controversy

The dating of fossilized footprints in New Mexico to about 22,000–23,000 years ago has forced archaeologists to reconsider these established timelines and sparked heated debate over the validity of methods, the reliability of stratigraphic evidence, and the possibility of earlier coastal migration routes.

“The immediate reaction in some circles of the archeological community was that the accuracy of our dating was insufficient to make the extraordinary claim that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. But our targeted methodology in this current research really paid off,” said Jeff Pigati, USGS research geologist and co-lead author of a newly published study.

Methods of Dating

The dating of the White Sands footprints relied primarily on radiocarbon dating of organic materials embedded in the ancient mud and sediments surrounding the tracks. Early studies focused on seeds from the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa, which were found interbedded with the footprints. These yielded consistent ages between about 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, placing the site within the Last Glacial Maximum.

“Three separate carbon sources – pollen, seeds, and organic muds and sediments – have now been dated by different radiocarbon labs over the course of the trackway research, and they all indicate a last glacial maximum age for the footprints,” said Jason Windingstad, a University of Arizona doctoral candidate in environmental science and co-author of the study.

Past Beliefs Being Challenged

For much of the 20th century, archaeologists broadly accepted the Clovis First theory, which held that humans first entered the interior of North America about 13,000 years ago and rapidly spread southward. These conclusions were based on widespread findings of distinctive stone tools at Clovis sites, which were considered the earliest reliable evidence for human occupation in the Americas.

This finding means that early Americans may have arrived by previously unknown routes, challenging the theory that migration only became possible once the ice corridors opened. Emerging evidence now supports the idea that humans could have traveled along coastal or ice-edge paths or possibly entered the Americas in multiple waves, using alternative strategies adapted to harsh climatic conditions.

Early Human Technology

Grooves discovered running parallel to human footprints indicate tracks that could only have been created by large objects dragged through soft, muddy terrain, matching the characteristic marks of a travois. Unlike wheeled vehicles, which would not appear in the archaeological record until much later, this was a framework made of two long poles joined together and dragged across the ground to carry heavy loads.

“Basically, it’s a wheelbarrow without the wheel,” said Matthew Bennett, study author from the University of Bournemouth. “Tracks like this occur in lots of different areas of White Sands National Park, so it was widespread. It’s not just one inventive family using a travois.”

Animal Interaction

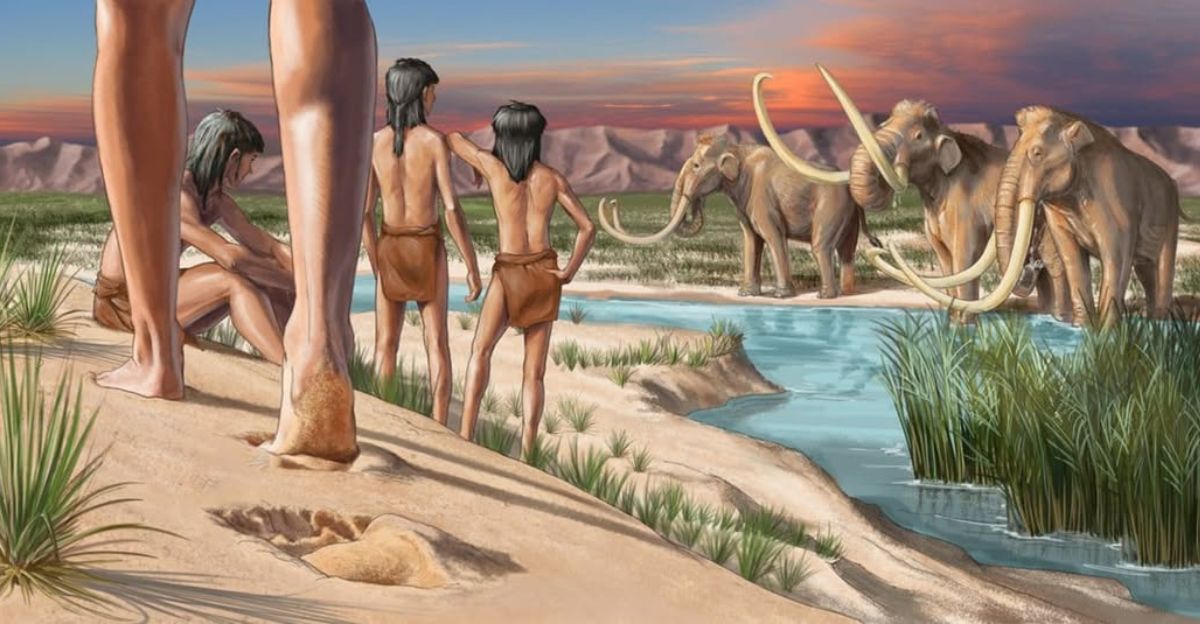

Across the ancient lakebed, human footprints are found moving alongside, and even inside, the prints of animals such as Columbian mammoths, Harlan’s ground sloths, dire wolves, American lions, and others.

“One set of footprints shows what appears to be humans stalking a giant sloth. This is demonstrated by human footprints being found inside the footprints of the sloth as they were tracked. Unfortunately for our hunter, there is no evidence that this was a fruitful hunt,” wrote NPS.

Rare Preservation

The preservation of the White Sands footprints is exceptionally rare. It results from a unique combination of environmental and geological factors that existed along the ancient shores of Lake Otero during the late Ice Age. These tracks are imprinted in fine-grained, gypsum-rich alluvium and clay-silt layers formed as wet and dry conditions alternated across the basin.

When humans and animals crossed these wet surfaces, their impressions sank into the clay-rich mud, which quickly dried and was subsequently buried by later deposits, sealing the prints away from destructive elements.

Landscape Reconstruction

Landscape reconstruction at White Sands National Park reveals a dramatic transformation from Ice Age grasslands to the modern arid dunefield. The region’s climate then was cooler and wetter, with the lake surrounded by extensive lush meadows, wetlands, and vegetation, supporting a rich diversity of wildlife and megafauna.

Sediment analysis and multiple radiocarbon datings of mud, pollen, and plant remains confirm that the footprints were left during “a mosaic of wet-and-dry environments,” with shallow lake waters and intermittently exposed floodplain surfaces.

Seasonal Movement Hypothesis

These fossilized tracks suggest that humans visited Lake Otero repeatedly over at least 2,000 years during the Last Glacial Maximum, likely moving in response to changing environmental conditions. Analysis of the footprint layers reveals multiple episodes of activity, separated by periods of surface stability and sediment deposition, indicating these were not one-time crossings but sustained, recurring interactions with the landscape.

“One hypothesis for this is the division of labor, in which adults are involved in skilled tasks, whereas ‘fetching and carrying’ are delegated to teenagers. Children accompany the teenagers, and collectively they leave a higher number of footprints preferentially recorded in the fossil record. This pattern is common to all excavated surfaces,” writes Bennett.

New Mexico’s Archaeological Significance

According to scientists, the site has provided “the best direct evidence of late Pleistocene interactions between humans and megafauna found anywhere in the world,” including hunting parties and child-carrying journeys. White Sands National Park remains a focal point for collaborative research and public education, involving local tribes and pueblos whose ancestors may have walked these very sands.

With hundreds of thousands of trackways yet to be fully studied and preserved, New Mexico stands at the forefront of Ice Age archaeology.

Implications for Migration Routes

Traditionally, it was thought that the first migrants crossed the Bering land bridge and entered the continent only after the melting of massive ice sheets about 16,000 years ago, following the so-called “ice-free corridor.” However, the footprints reveal that humans were in southern North America when northern routes were locked under ice and thus impassable.

This discovery indicates that these earliest Americans must have found alternative pathways, most likely along the Pacific coast by sea or skirting the edges of glaciers.

Family and Group Patterns

Analysis of footprint size and stride has allowed researchers to estimate not only the age and sex of individuals but also the dynamics of travel and group movement, including round-trip journeys and shared tasks.

Scientists also interpret other sets of footprints as evidence of children playing, jumping in puddles, or between the tracks of giant animals, hinting at communal activities, playful behaviors, and the transmission of cultural knowledge within family groups.

Unanswered Questions

Despite the remarkable evidence revealed by the White Sands fossil footprints, the archaeological community still has numerous unanswered questions regarding the first Americans. The primary controversy revolves around the accuracy and reliability of the dating methods, specifically, whether radiocarbon dating of aquatic plant seeds (Ruppia cirrhosa) from footprint layers provides a true age or is skewed by “old carbon” from groundwater.

Questions also persist about the behaviors and lifeways of these ancient peoples: Did the footprint-makers live at Lake Otero year-round or only visit seasonally? Were they part of established populations or transitory families on the move?

Methodological Advances

Initially, researchers dated the footprints using radiocarbon dating on seeds from the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosa, drawn from the clay-rich sediment in and around the footprints. This method, however, was questioned due to concerns about “old carbon reservoir effects”.

To address these issues, the research team expanded its approach by applying radiocarbon dating to terrestrial pollen in the same sedimentary layers. This material is far less likely to be contaminated by ancient groundwater carbon, and using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating to measure when quartz grains in the footprint layers were last exposed to sunlight.

Potential for Further Discoveries

Recent advances in dating methods and multidisciplinary approaches have already established that the White Sands footprints are likely the oldest confirmed tracks in North America. Still, experts believe that only a fraction of the ancient record has been revealed.

As environmental changes and erosion regularly reshape the landscape, researchers race to document tracks that may soon be lost forever. “We’re racing to document what we can,” notes archaeologist David Bustos.

Shifts in Academic Consensus

Some archaeologists urge caution, advocating for further fine-scale sampling and stratigraphic verification before declaring the debate settled. Others point out the absence of artifacts at the site, which they argue complicates the narrative, yet the consensus is shifting as the evidence accumulates.

“You get to the point where it’s really hard to explain all this away,” said. “As I say in the paper, it would be serendipity in the extreme to have all these dates giving you a consistent picture that’s in error,” said Vance Holliday, a professor emeritus of anthropology and geosciences at the University of Arizona.

Influence on Public Imagination

Media coverage, museum exhibits, and educational outreach have made the site and its evidence tangible for the general public, who now see in the ancient tracks a vivid story of families, children, and even dramatic hunts unfolding over 20,000 years ago.

The White Sands discoveries have inspired new exhibits and projects, such as casted footprint displays and interactive videos at the park’s visitor center. These draw thousands of visitors each year who are eager to glimpse humanity’s past and understand their place in Earth’s timeline.

Call for Continued Research

While the footprints’ dating to 21,000–23,000 years ago has been corroborated by radiocarbon and mud analysis, independent laboratory corroboration, and multidisciplinary review, scholars emphasize that further investigation is crucial.

Critics and proponents agree that additional geological sampling, rigorous cross-lab testing, and new fieldwork are needed, especially to address significant gaps like the lack of contemporaneous artifacts or settlements associated with the trackways.