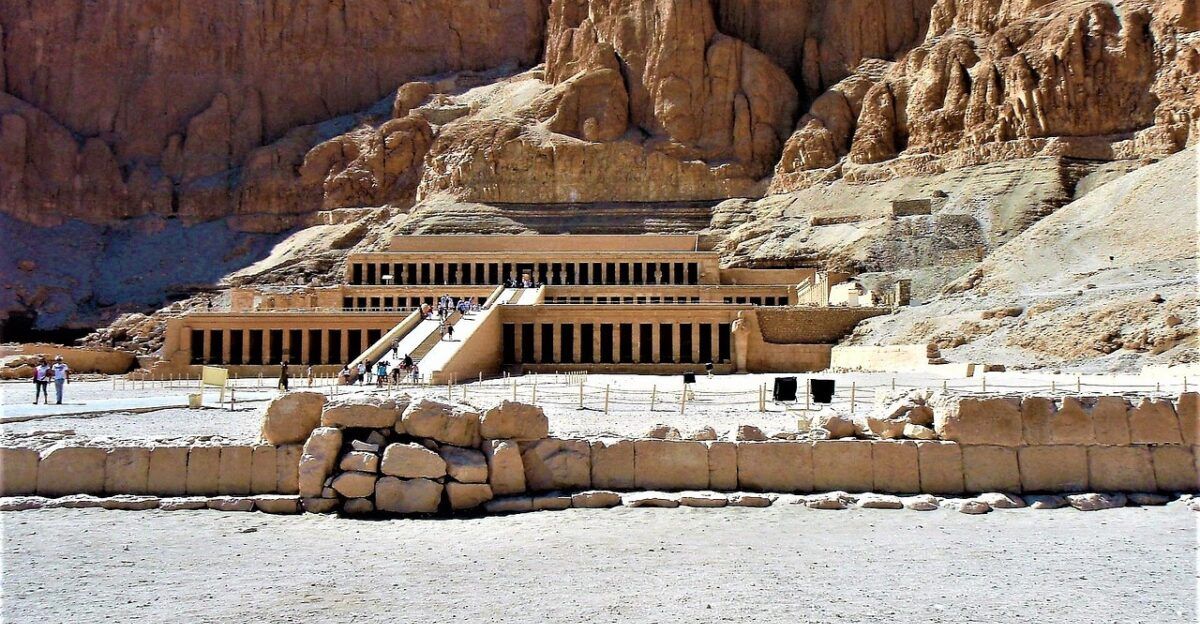

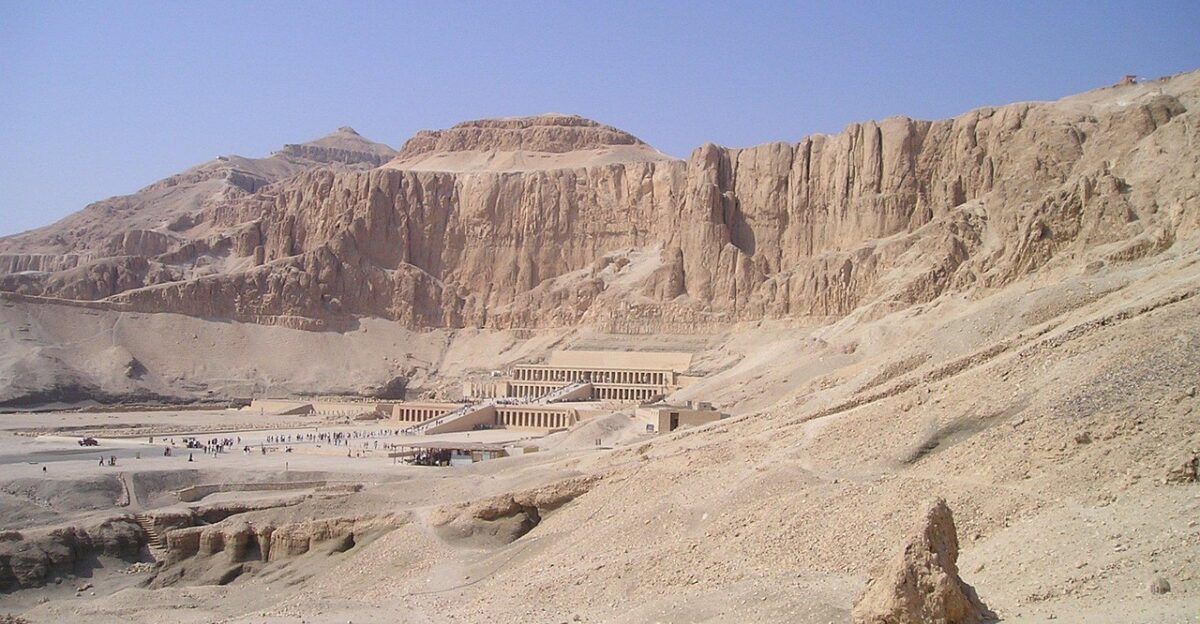

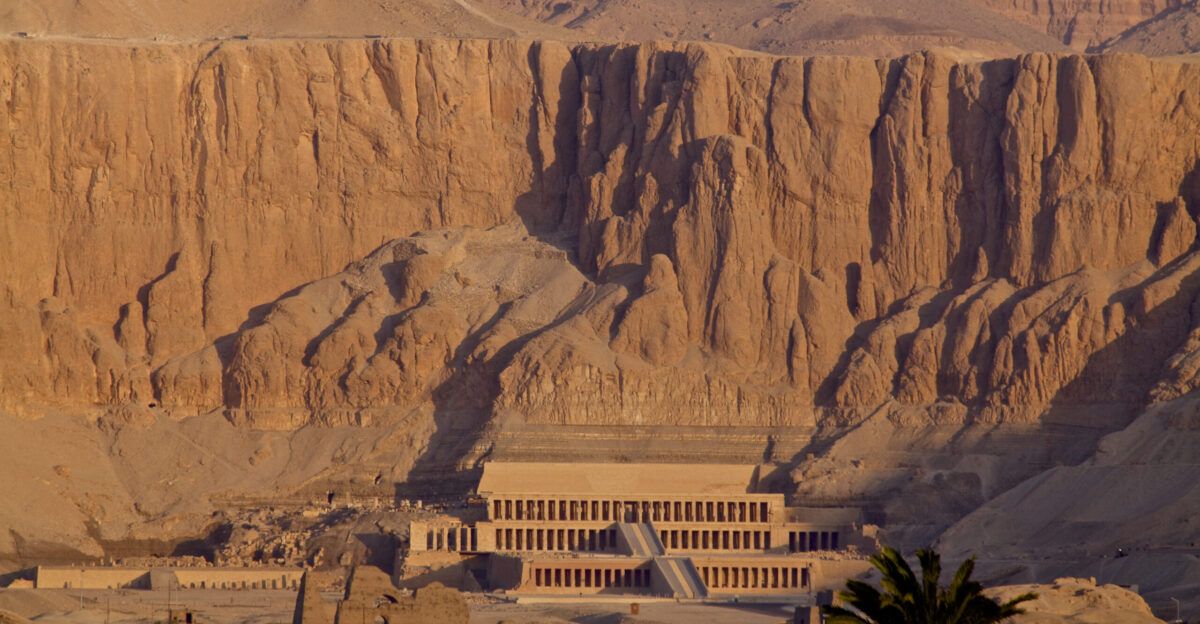

Archaeologists led by Zahi Hawass have made a significant discovery near Luxor, Egypt.

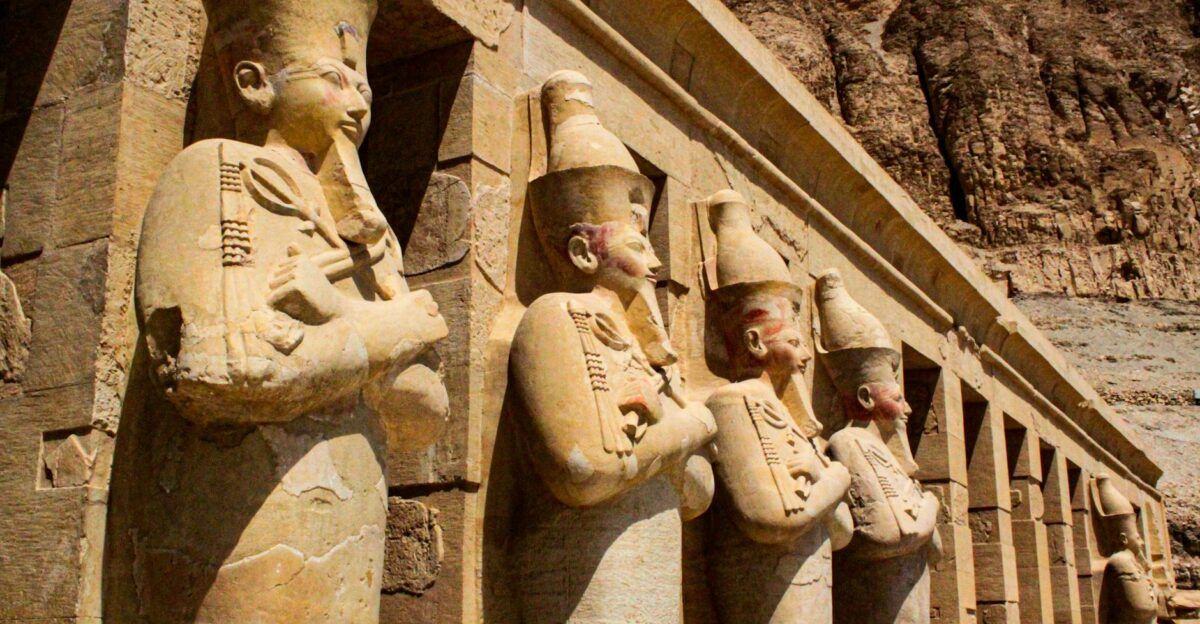

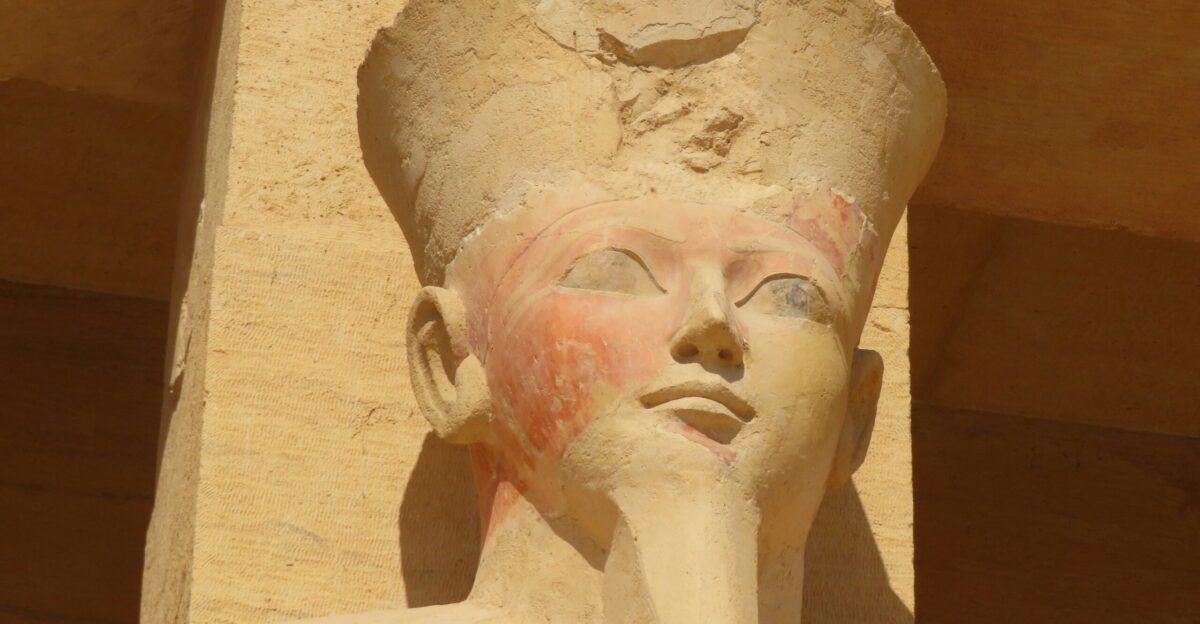

Since September 2022, they have found over 1,500 decorated stone blocks at Queen Hatshepsut’s Valley Temple at Deir el-Bahari. These blocks still have bright colors after 3,500 years and show images of Queen Hatshepsut and her stepson, Thutmose III.

This is the largest and most complete group of blocks from this temple. The team also found burial shafts with coffins from the 17th Dynasty and the tomb of Queen Tetisheri, the grandmother of Ahmose I, the pharaoh who defeated Egypt’s Hyksos rulers.

Hidden Treasures

The dig has uncovered objects that show royal life and religion in ancient Egypt. The team found tools for building, like hammers, chisels, and a wood-cutting adze, all marked with Queen Hatshepsut’s name.

As a special ceremony, these items were buried when the temple was first built. They also found a limestone tablet named Senmut, Hatshepsut’s famous architect, who built the temple.

Experts say these discoveries are the most important of their kind, made over 100 years ago, and help us understand how temples were built and why they mattered.

Stones with Hatshepsut’s name prove the temple’s royal and religious importance.

Power Struggle

This discovery changes what many people thought about Queen Hatshepsut and her stepson, Thutmose III.

In the past, historians believed Thutmose III tried to erase Hatshepsut from history by destroying her monuments after she died. But the new blocks show their names together and prove that Thutmose III fixed up or restored this temple instead of destroying it.

Zahi Hawass says this means Thutmose III still honored Hatshepsut at the temple even after her death.

This suggests their relationship was more complicated than the old story, and Thutmose III may have respected his stepmother instead of trying to wipe out her memory.

Desert Connections

In another part of Egypt, near Aswan in the south, archaeologists found ancient rock art that might show one of Egypt’s first rulers from about 5,100 years ago.

The precise carving shows an elaborate boat being pulled by five people, and someone important sitting in what looks like a special chair.

This person has a long chin, which could mean he wore the pharaoh’s false beard. The artwork was found in November 2022 during checks before building New Aswan City.

It gives a rare look at the time before Egypt was united, and its high quality suggests it was made by leaders trying to show their power and control over the land.

Royal Revelation

The main discovery at Deir el-Bahari is more than random artifacts—it’s the most complete set of decorated temple blocks ever found from Egypt’s 18th Dynasty.

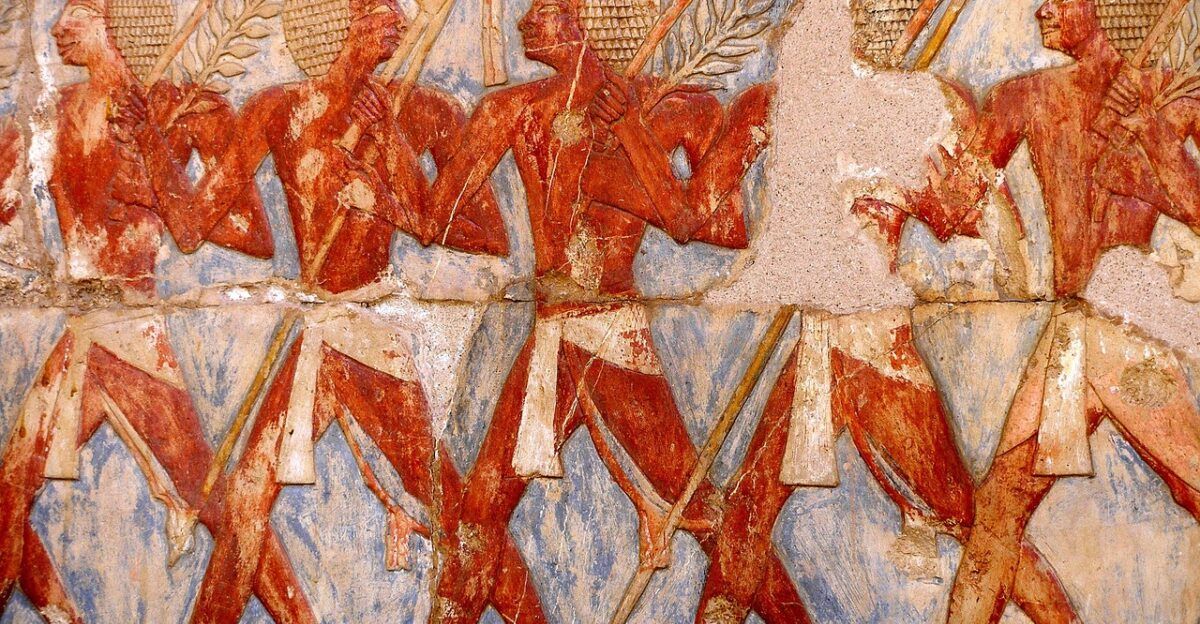

One thousand five hundred blocks with brightly colored scenes showing Queen Hatshepsut and Thutmose III doing religious ceremonies. Even after thousands of years, red, blue, and gold are bright.

These pictures give us a rare look at the religious rituals held at the entrance of Hatshepsut’s temple, showing her as a powerful pharaoh.

These blocks formed the temple’s foundation wall, greeting visitors to one of Egypt’s most important religious places. Zahi Hawass called them “the most beautiful scenes I’ve ever seen,” showing how special the find is for art and history.

Regional Impact

These discoveries have excited Egypt’s tourism and archaeology teams. More than 300 journalists from Egypt and other countries visited Deir el-Bahari for the big announcement.

The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities believes these finds are significant for attracting visitors, which helps Egypt’s economy. The finds cover different periods and help experts understand Egypt’s history from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom.

People living in Luxor feel proud that their area is getting worldwide attention for its history.

In the future, the artifacts will be displayed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo for researchers and tourists to see.

Human Stories

Archaeologists found touching signs of how ancient Egyptians lived during hard times inside the burial shafts.

They uncovered wooden coffins from the 17th Dynasty holding people who went through Egypt’s fight against foreign Hyksos rulers, along with weapons like bows and arrowheads, possibly used in those wars.

One especially emotional find was a child’s coffin from about 3,600 years ago, buried with toys and personal belongings.

Queen Tetisheri’s tomb was simple, with drawings on the walls, showing that money was tight while Egypt was recovering from foreign rule.

Unlike the rich tombs built later, her modest burial shows how tough times even affected Egypt’s royalty.

Scientific Analysis

Because the blocks are so well preserved, experts can study ancient Egyptian art skills up close like never before.

Tests on the paint show the artists used many colors and special ingredients. By closely recording the styles of the carvings, researchers can tell what order the temple was built in.

The tools and stones buried at the site teach us how Egyptians held rituals to protect their buildings, asking the gods for help. High-tech photos and scans capture even the most minor details so nothing is lost, while comparing these finds with museum items from around the world puts everything in context.

The stone with Senmut’s name helps us understand how vital architects were in Egypt and what they meant to the pharaohs.

Market Implications

These discoveries are critical for Egypt’s tourism, which has had problems because of political troubles and COVID-19.

The new finds are giving travel companies and museums exciting stories to attract more visitors—especially those interested in Queen Hatshepsut and the latest artifacts.

News coverage worldwide has already made more tourists, experts, and filmmakers want to visit the sites. Egypt’s government sees these discoveries as proof that its efforts and spending on archaeology are working.

Officials hope the finds will help start a new, busy period for Egypt’s archaeology—bringing in attention and money from around the globe.

Hidden Network

One of the most interesting discoveries happened outside of Egypt. In Jordan’s Wadi Rum desert, archaeologists found the first-ever Egyptian royal inscription in that country—a carving of Pharaoh Ramesses III’s name from about 1180 BCE.

This was discovered near the Saudi border, beside old trade routes. It shows that Egypt’s power and influence reached much further into the Arabian Peninsula than people used to think.

The carving includes the king’s birth and throne names, proving it was an official mark from Egypt’s rulers, not just a random traveler. This find changes how experts view ancient trade, showing that Egyptian pharaohs controlled important routes for goods like frankincense, copper, and spices from Arabia.

Because it was found along the famous “Incense Road,” it suggests that Egypt systematically managed trade and business far from the Nile Valley.

Internal Tensions

At Deir el-Bahari, archaeologists found burials from the 17th Dynasty that reveal tough times in Egypt’s past, known as the Second Intermediate Period.

The cemetery held the remains of officials who fought against the Hyksos, foreign rulers who took over northern Egypt and made their capital at Avaris.

Weapons in the graves, such as special bows brought in by the Hyksos, show that Egyptians learned to use new military tools to regain their freedom.

The discovery of “Rishi” coffins, which have feather-like patterns, proves that Egyptians kept their traditional burial customs even under foreign control.

These burials help us see the people who helped drive out the Hyksos and started Egypt’s New Kingdom.

Ownership Shifts

By studying the decorated blocks, experts have learned more about how Hatshepsut and Thutmose III treated each other’s legacies.

Instead of destroying everything, Thutmose III often just changed some of Hatshepsut’s monuments by adding his name to hers, not covering hers up. This shows he was smart politically—he wanted to be accepted as the new ruler but didn’t want to erase a successful queen.

The temple was taken apart centuries after their time by rulers from the 19th or 20th dynasties who tried to remove traces of Egypt’s famous female pharaoh.

The pieces were carefully buried instead of smashed, so later generations could still find and study them.

This also shows that even later pharaohs respected the artworks and religious importance of Hatshepsut’s monuments.

Response Strategies

Modern Egyptian officials are working hard to protect and study the newly found artifacts. The Supreme Council of Antiquities keeps the decorated blocks safe in special storage while experts record and examine every detail.

They’re using modern technology, such as 3D scanning and high-quality photos, to save images of the blocks before they can be damaged. Museums in Luxor and New York are working together to compare these new finds with similar items discovered in the past.

Plans also include building display spaces with controlled temperature and humidity so people can see the blocks without risking damage from light or moisture.

Recovery Timeline

This excavation results from three years of organized work that started in September 2022. First, archaeologists looked for the best spots to dig near Hatshepsut’s temple.

When they found the decorated blocks in late 2024, they began a bigger dig that uncovered most of the old temple remains. Every block had to be recorded, photographed, and checked for damage before moving.

The project will continue through 2025, as experts study the artifacts and prepare them for a museum.

Scientists will likely take several more years to fully understand what these discoveries mean for Egypt’s history.

Future Implications

These discoveries could seriously change what we know about Egypt’s politics, religion, and relationships with other countries.

The blocks from Hatshepsut’s temple help experts learn more about how art and religion worked in the 18th Dynasty. The carving of Ramesses III in Jordan also opens up new ways to study Egypt’s trading and contact with other lands.

If digs continue in both places, there may be even more to find. This shows that careful, long-term digging teaches us the most about history.

As technology improves, these ancient objects will keep giving researchers new information for many years, showing how vital Egypt’s civilization was to the ancient world.

Emerging Research

Researchers now look beyond the first discoveries to learn more about ancient Egyptian life. They are using new carbon dating methods on things found with the artifacts to get better dates for the 17th and 18th dynasties.

Experts also use radar and pictures from space to check if other valley temples might be buried at different pharaoh sites. Because of the Ramesses III find in Jordan, archaeologists are now searching old trade routes for more signs of Egyptians in Arabia.

Scientists are even testing DNA from mummies to see if people buried there were related or worked for different pharaohs.

All these new studies could help us discover new things about ancient Egypt in the next few years.

Industry Connections

These discoveries are changing archaeology and preservation worldwide. New ways of recording and protecting the Hatshepset temple blocks are now being used at other old and fragile sites that face environmental risks.

Museums in different countries are working together to create digital records with detailed images and information that researchers can access online.

The success of the Deir el-Bahari project is leading to more money being given to similar, long-term archaeology projects in Egypt and other countries with ancient history.

The tourism industry is also creating new programs that help visitors learn about the digging and research process, not just see the artifacts.

This means archaeological finds are now being studied, saved, and shared with the public in more modern and connected ways.

Public Reaction

Social media has made the discoveries very popular worldwide, with photos of the colorful blocks and ancient artifacts seen by millions of people.

However, this attention has also caused problems, like the spread of false stories about secret tunnels or “cursed” objects. Egypt’s officials are working with social media companies to ensure correct information is shared and to stop rumors and fake news.

Experts remind everyone that real archaeological finds take years to study and understand thoroughly, even if people want instant answers. Because of all the excitement, more students are signing up to study archaeology and Egyptology at universities.

These discoveries show that when trustworthy sources explain real research, it can inspire and interest people everywhere.

Historical Precedent

These discoveries are similar to some of the most significant archaeological finds of the last 100 years, like when Howard Carter found King Tut’s tomb in 1922 or when experts unlocked secrets about ancient Egyptian medicine.

Like those earlier discoveries, they took years of careful digging and recording before people understood their importance. Working together with other countries is also a big part of these projects.

Today’s archaeologists can study ancient items in much greater detail than before, using modern tools and science.

Unlike quick treasure hunts from the past, the team at Deir el-Bahari is taking a slow, scientific approach focused on learning as much as possible, not just making exciting headlines.

The Bottom Line

These archaeological discoveries are more than just amazing old objects; they show how complex and connected ancient civilizations were.

Instead of seeing Queen Hatshepsut as a forgotten queen, the evidence proves she remained essential and worked with later rulers. The writing in Jordan also shows that Egypt’s power and trade stretched far beyond the Nile, linking Africa, Asia, and Arabia.

These finds highlight why careful, long-term archaeology is essential for people today: it gives us fundamental, trustworthy knowledge about the past.

Because of advanced methods and people working together across countries, we will save and share these ancient stories and secrets for many years.