Global Internet traffic rides on fragile undersea cables. Nearly 99% of intercontinental data flows through these lines, yet accidents happen often. Experts report 150–200 cable faults per year, with roughly 70–80% caused by human activity (fishing nets, dropped anchors, etc.).

Because data automatically reroutes around a break, many of these failures go unseen until they pile up. In effect, the world’s “digital highway” has no dashboard reporting that it’s decaying beneath the waves.

This invisible crisis makes global communications highly vulnerable to a single incident.

Escalating Risks

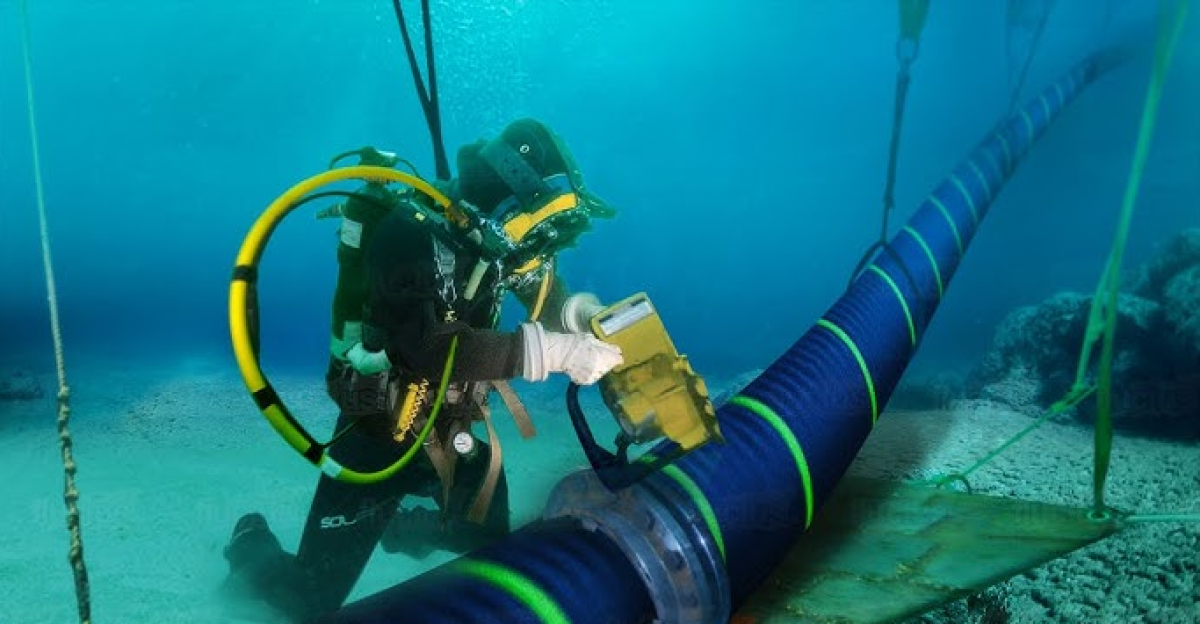

Even a minor cable cut triggers a major scramble. Only about 80 specialized cable ships exist worldwide to repair faults. When a cable breaks, locating the fault and sailing a repair ship to the site typically takes weeks, on average, 40 days.

The operation itself is expensive (often $0.6–1.3 million per repair) and can be delayed by geopolitics or heavy maritime traffic. For example, international disputes or extra security at chokepoints like Suez or Bab el-Mandeb can slow access to a fault.

Any escalation (routine or political) translates into longer outages: an ocean liner’s detour or port congestion can turn a short outage into a month-long communications crisis.

Strategic Weakness

The Red Sea serves as a critical digital bridge between continents. Undersea lines there connect Europe, Asia, and Africa – but the network routing is lopsided. Even within the Middle East, most data must loop through Europe.

A recent study found 83% of Middle Eastern Internet traffic transits European hubs like Frankfurt or Marseille. In Lebanon, for instance, local data is still sent via Europe simply because of legacy routing. In short,

this geographic dependency creates chokepoints: a break near Jeddah or Djibouti can pull the plug on cross-continental connections. Put another way, single points of failure in Far Eastern cables can knock out networks for billions of users downstream.

Growing Pressures

Geopolitical flashpoints have made these submarine routes ever riskier. Security firms report that in just the last two years, eight cables were cut in the Baltic Sea and five near Taiwan.

Many of those incidents involved suspicion of foreign vessels: for example, intelligence analysts traced several Baltic cuts to anchors dropped by Russian-linked ships, and Taiwan’s regulators noted Chinese survey ships operating strangely whenever their own cables went dark.

Such disruptions were once rare; now experts warn that every major sea lane carries an undercurrent of tension. Incidentally, these 2024–25 events resemble the Red Sea case – they show how easily routine shipping can become a national security issue, exacerbating the hidden risk beneath the sea.

Breaking Point

On the weekend of Sept. 6–7, 2025, the worst occurred: multiple undersea cables were severed in the Red Sea near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Investigators identified cuts to the SMW4 (South-East Asia–Western Europe 4), IMEWE (India–Middle East–West Europe), FALCON/GCX (Gulf sub-sea system), and Europe India Gateway lines.

The outages instantly choked internet links to Asia and the Middle East. Network monitors (NetBlocks and others) showed that India, Pakistan, the Gulf states, and East Africa all saw degraded connectivity in the aftermath.

The affected carriers – from India’s Tata Communications to Kuwait’s GPX – confirmed losses in their traffic, even as Saudi authorities remained unusually quiet about the incident.

Regional Impact

Local operators scrambled to explain the outages. Pakistan’s largest ISP, PTCL, warned citizens on Saturday: “Internet users in Pakistan may experience some service degradation during peak hours,” acknowledging cuts to international fibers. In Kuwait, officials confirmed that the FALCON/GCX submarine cable had been severed, causing disruption in that oil-rich nation.

In the UAE, customers of Du and Etisalat logged slower speeds, and telecom watchdogs acknowledged general congestion on their networks.

Even India’s networks saw partial slowdowns. Notably, neighboring Saudi Arabia – under which the cuts occurred – gave no public comment, reflecting a common pattern: governments seldom admit when their own digital “backyard” is struck. For users in these countries, the break translated into buffering streams, stalled video calls, and uncertain data transfers as engineers rerouted traffic.

Human Cost

The outage stirred political concerns. Yemen’s Information Minister Moammar al-Eryani framed it as a direct threat: “What is happening today in the Red Sea should serve as a wake-up call…to stop these escalating threats and protect the digital infrastructure that serves as the lifeline of the modern world,” he warned.

His comment highlights that even innocent citizens feel the pain of submarine failures: farmers tracking crop markets online, students sitting idle during tech classes, or doctors awaiting critical lab results can all lose service without warning.

In villages along the Red Sea, fishermen suddenly found satellite chat apps stalling, while businesses hours away on other continents noticed payment systems lagging. These disruptions underscore a human reality: underneath the global “cloud,” physical cables carry our livelihoods.

Corporate Response

Major tech companies quickly reassured users. Microsoft, for example, acknowledged on Sept. 6 that Azure clients “might experience increased latency” due to the cut cables. The company’s engineers then rerouted traffic through alternate routes, away from the Red Sea, and continuously “rebalanced and optimized” the network.

By Saturday night, Microsoft reported it was no longer detecting any Azure issues, meaning its customers’ cloud services were functioning normally again.

Even so, internal reports indicated the substitute paths were not ideal: packets were taking longer routes around Africa or through Persia, keeping some latency higher than usual.

Infrastructure Vulnerability

The balance sheet is stark: submarine cables carry ~97–99% of global internet traffic, yet only about 80 repair ships exist worldwide. Most of those vessels were built in the 1990s or early 2000s – roughly 20–30 years old – and are booked solid.

According to industry consultants, projects often await an open ship slot for months or years. When cables break, the bottleneck isn’t locating the damage (which modern diagnostics do quickly) but getting a repair crew on site.

The average fix already takes six weeks, and experts warn bureaucratic hurdles (licensing a foreign ship in territorial waters, security clearances, etc.) could easily stretch it much longer. This small, aging repair fleet creates a critical capacity crunch – even minor underwater damage can now cause multi-week outages and spiraling costs for global commerce.

Hidden Truth

Behind the disaster lies an inconvenient fact: most cable cuts are accidents, not acts of war. According to the International Cable Protection Committee, roughly 30% of yearly faults trace to ships dragging anchors over cables.

This incident appears to fit that pattern. It echoes an earlier Red Sea case: in Feb. 2024, a ship called the MV Rubymar was struck by a missile, drifted, and dropped anchor – which, investigators later concluded, likely sliced three cables along its path.

“It’s generally accepted that the Rubymar dropped an anchor… and as a result, it damaged cables in proximity,” said Ryan Wopschall of the ICPC. A commercial vessel’s emergency anchoring may have hit multiple fibers at once.

Industry Frustration

Cable companies and repair contractors have long complained that the economics make fixes difficult. Maintenance contracts are typically short-term (often just a few months), and profit margins are slim, offering little incentive to build or fund new ships. Meanwhile, telecom veterans note that most cable ships are themselves decades old.

As one industry executive, Gavin Tully of Pioneer Consulting, put it: “There were a lot [of ships] built about 20 to 22 years ago…projects are really at the mercy of ship availabilities.”

The pipeline of new vessels has dried up, and the remaining fleet is overstretched. It doesn’t help that recruiting at-sea crews is harder than ever: no one in their 20s dreams of a six-week deployment on a slow vessel with spotty broadband of its own.

Market Concentration

The supply chain for submarine cables is remarkably narrow. As analysts at the Center for Strategic and International Studies note, roughly 98% of all subsea cables are manufactured and laid by four companies.

The U.S. firm SubCom, France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN), Japan’s NEC, and China’s HMN Technologies (formerly Huawei Marine) dominate the market.

This oligopoly introduces new risks. If even one manufacturer has delays – for example, geopolitical pressures that slow Chinese factories – it constrains the whole industry. Critics also highlight that heavy Chinese involvement (through HMN) in global cable projects could raise security or political concerns.

Recovery Efforts

Once the immediate threat was contained, engineers moved to steady operations. Microsoft’s team “continued to work nonstop” over the weekend to reroute and balance traffic. Within 48 hours, most clients were back to normal: the Azure status page showed no ongoing issues by Sunday.

Meanwhile, other networks reported improvements as alternate cables took up the slack. The Red Sea cables themselves, however, remained under repair. Experts stressed patience: undersea fiber repair is a slow process, so carriers prepared for reduced speed service for days to come.

In many ways, the worst-case scenario was averted — no country went fully offline — but for affected users, the return to normal was gradual.

Expert Skepticism

Security analysts warned that early recovery estimates were optimistic. Kentik’s Doug Madory, a noted internet infrastructure tracker, stressed that far more countries saw trouble than first acknowledged. “At least 10 countries in Asia, the Middle East, and even Africa have experienced disruptions,” he told Reuters.

That tally exceeded the initial list of India, Pakistan, and Gulf states. Madory’s broader point: submarine failures often have hidden ripple effects. Industry sources point out that since repair crews are stretched thin, full restoration could still take weeks, especially if regional tensions hamper ship movements.

One analyst warned that diplomatic clearances and insurance paperwork in such volatile waters can delay a fix by as much as a month or more.

Future Implications

This episode lays bare a sobering truth about our digital age. As retired Admiral James Stavridis puts it, undersea cables are “the arteries of the modern world.” Any significant damage—whether from accident or attack—can choke off commerce and communication worldwide.

Our economy, supply chains, and even critical services have come to depend on uninterrupted data flow. High-frequency trading, remote surgery, cloud work, and live-streamed classes all assume a glitch-free internet.

Catherine De Bolle of Europol warns, “This isn’t just about internet connectivity… we’re looking at a potential trigger for systemic financial instability.” In an era of simultaneous globalization and digitalization, that instability could cascade rapidly: a severed cable might slow stock trades, delay financial confirmations, or isolate markets.

Geopolitical Ramifications

Politicians quickly reacted. Yemen’s government immediately blamed the Houthi militia, calling the cuts the latest “direct attacks… by the Houthi militia.” The rebels, however, once again denied targeting communications infrastructure.

Across the Gulf, pundits noted that the cables lie within striking distance of Iranian-backed groups focused on the Israel-Hamas conflict. In Washington, State Department officials said they were “closely monitoring” the situation.

While there is no public indication of deliberate sabotage, diplomats worry that any strike on critical infrastructure – even “collateral” damage – could inflame regional tensions.

International Response

The incident underscores how local conflict can cause international fallout. Since late 2023, Houthi rebels have attacked over 100 commercial vessels in the Red Sea, sinking four and killing crewmen. These attacks – framed by the Houthis as pressure on Israel – have already made the Red Sea one of the world’s most dangerous shipping corridors.

By cutting subsea cables, the latest incident shows that those maritime assaults can inadvertentlycripple regional Internet.

Global leaders reacted with concern but cautious wording: official statements emphasized resilience and technical fixes, not blame. In many ways, this cable cut demonstrated the interconnectedness of conflicts.

Security Concerns

Experts say hostile state actors are eyeing cables. Recent research notes a worrying pattern: since 2018, Chinese vessels have been implicated in 27 separate disruptions of the undersea cables supplying Taiwan’s offshore islands.

Similarly, damage to a Sweden-Estonia telecom cable last year was linked to a Russian-flagged ship operating nearby.

These incidents suggest cables are viewed as strategic targets in a new “gray zone” warfare – attacks that fall short of full-blown war but can inflict economic harm. The Red Sea cuts add to this picture, even if caused by accident: they highlight how any regional skirmish offers cover for ambiguity.

Digital Divide

Perhaps the most tragic lesson is for developing regions. Where redundancy is scarce, a single cable cut can isolate entire countries. For example, in March 2024, one cable failure knocked 10 African nations offline simultaneously. Analysts at Recorded Future warn that places with “low redundancy, such as parts of West and Central Africa,” are especially vulnerable to any break.

By contrast, wealthier nations route traffic over multiple cables and satellites, so an outage in one chokepoint barely disrupts their service.

The Red Sea incident highlights this digital inequality: broadband-rich hubs and data centers outside the region saw only a blip, while populations in emerging economies – reliant on a few fragile links – faced potential days of slower connectivity.

Connected Vulnerability

These Red Sea cuts reveal an uncomfortable truth: the hyperconnectivity we take for granted rests on a delicate physical web. With 97+% of data crossing oceans via a few skinny fiber-optic lines, the entire global network becomes only as strong as its weakest cable.

The EU’s cybersecurity agency (ENISA) even warns that a “coordinated attack against multiple subsea cables could have a major impact on global internet connectivity.”.

In other words, severed cables could trigger waves of disruption in finance, communications, and social infrastructure. As one analyst observed, the world must now treat cable protection as seriously as any national security issue. Going forward, strengthening submarine networks – through redundancy, monitoring, and international cooperation – is not just an engineering task but a core requirement for global stability.