Two people in France are fighting for their lives against a virus most Europeans have never heard of. In early December 2025, health officials confirmed the first cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in France since 2013. The virus kills roughly one in three people it infects—far deadlier than COVID-19.

For healthcare workers bracing for what comes next, the question isn’t whether the virus can return to Europe. It already has.

Two Cases Confirmed In France

The alarm began when French laboratories confirmed two MERS-CoV infections in travelers returning from the Arabian Peninsula. Health authorities moved swiftly, isolating patients and launching contact tracing.

A single traveler boards a plane. A few days later, symptoms begin. Now, entire hospital wards are on alert. This is how outbreaks typically begin: with one person, one flight, one hospital visit.

More Dangerous Than COVID-19

While the world grappled with COVID-19’s roughly 1% fatality rate, MERS-CoV kills approximately 37% of those confirmed infected. That’s roughly 37 times deadlier. Since 2012, nearly 1,000 people have died from this virus globally.

The World Health Organization considers MERS one of the most severe coronaviruses known.

A Distinct Coronavirus Threat

MERS is a coronavirus, but the comparison ends there. This virus doesn’t transmit easily through casual contact. Instead, it exploits hospitals, turning them into amplification chambers. Experts worry that while laboratories were focused on SARS-CoV-2, MERS cases may have been missed entirely.

A patient with identical respiratory symptoms, tested only for COVID-19, might have gone home undiagnosed.

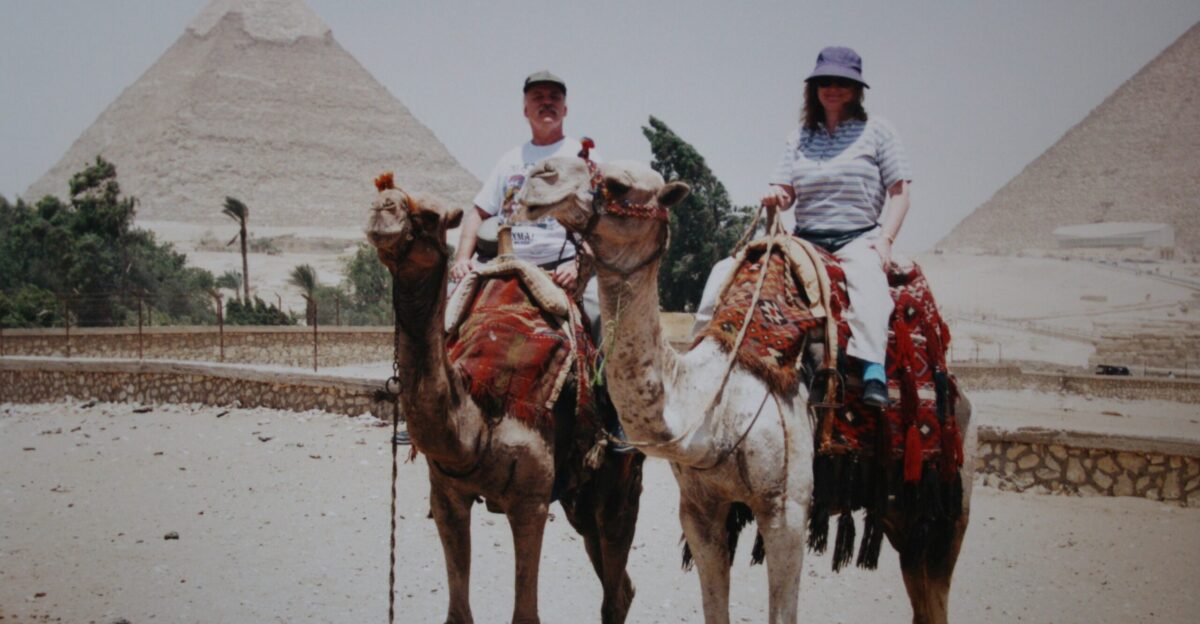

Tracing The Zoonotic Source

Every MERS outbreak can be traced back to the same origin: dromedary camels. Somewhere in the Arabian Peninsula, a herder touches a camel, and a virus crosses species. The World Health Organization confirmed on December 24, 2025, that the virus “continues to pose a threat in countries where it is circulating in dromedary camels,” with regular spillover triggering new human cases.

These aren’t isolated incidents. They are predictable, recurring events that no border can stop.

How The Virus Spreads

Once in humans, the virus reveals its danger. It doesn’t spread through crowded streets but through intimate moments of care. A nurse leans close to help a struggling patient. A doctor intubates someone in respiratory distress, aerosol particles filling the air. In these moments, the virus finds its path.

Human-to-human transmission is rare in the community but devastatingly efficient in hospitals, where the sick and vulnerable gather.

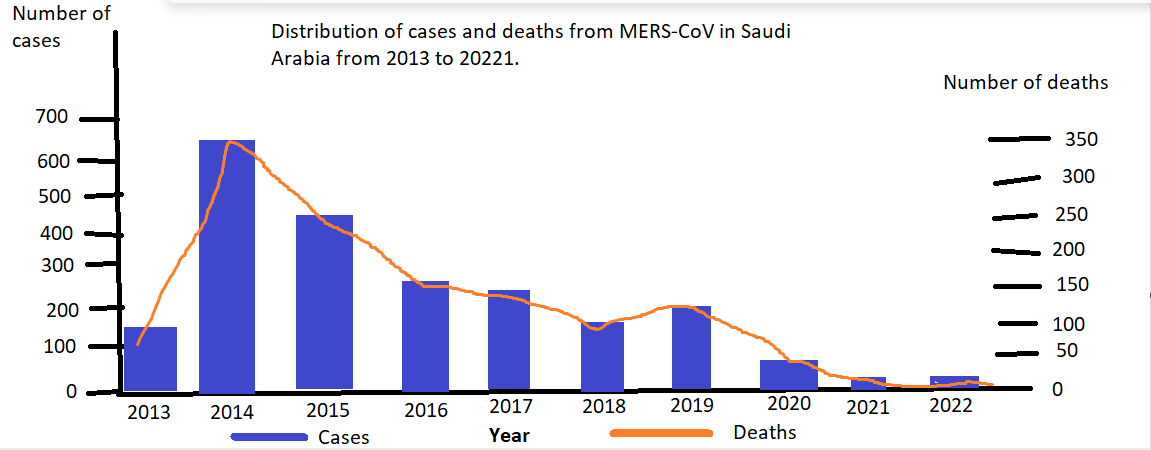

The Global Toll So Far

Since 2012, there have been 2,635 laboratory-confirmed cases across 27 countries spanning all six WHO regions. Nearly 1,000 people have died. These aren’t pandemic-scale numbers, which is perhaps why MERS has persisted so silently.

Persistence combined with lethality is its own kind of threat. A virus that kills steadily in the shadows for twelve years is still a virus that kills.

A Quiet But Deadly Year

As of December 21, 2025, the world has recorded 19 confirmed MERS cases. Four of those patients are dead. Nineteen cases may seem manageable compared to the millions affected during COVID-19. But each case represents a chain of human contact.

Each death represents a family grieving someone lost to a virus with no cure. The year 2025 is shaping up to be a year where MERS proves its lethality once again.

The Saudi Arabian Connection

If MERS has a heartland, it is Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom accounts for roughly 84% of all cases—2,224 infections and 868 deaths concentrated in a region where the virus has established its presence. But travelers don’t stay put. Pilgrims visit. Business people fly out. Families return to other countries.

France’s two cases are the latest in a long chain of international spillovers, each one a reminder that geography offers no shelter.

Learning From South Korea

In 2015, the world witnessed what MERS could do outside its endemic region. A single traveler returned to South Korea from the Arabian Peninsula. Within weeks, 186 people were infected. Thirty-eight died. Hospitals were forced to close wards. Healthcare workers fell ill.

That outbreak exposed how rapidly a contained virus could transform into a catastrophe given the right conditions: modern healthcare systems, sophisticated patient interactions, and a virus that exploits both.

Identifying The Symptoms

Here lies the trap. A patient walks into an emergency room, feverish, coughing, struggling to breathe. Doctors see flu. They see COVID. Without explicit suspicion or a travel history being asked, they might see nothing unusual. The symptoms of MERS are generic: fever, cough, shortness of breath, and sometimes gastrointestinal distress.

A person infected could be sent home, told to rest. By the time diagnosis arrives, days have passed, and people have been exposed.

The Danger Of The Waiting Period

The virus’s incubation period is a window of vulnerability. Symptoms can appear between 2 and 15 days, with an average of 5 days. During this window, an infected person is a biological time bomb. They board planes. They embrace family. They visit hospitals.

This invisible phase is where surveillance often fails, allowing disease to spread.

No Vaccine After Twelve Years

The silence is deafening. Twelve years of this virus circulating. Nearly 1,000 deaths. A 37% fatality rate. And yet, no vaccine. No specific treatment. No antiviral drug. Supportive care—encompassing oxygen, ventilation, and organ support—is all modern medicine can currently offer.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine development progressed at an unprecedented speed. For MERS, despite higher death rates, progress has stalled.

The Threat To Healthcare Workers

Nurses and doctors entered their professions to heal, not knowing which patient carries an invisible killer. With MERS, the risk is acute. Procedures that generate aerosols—such as inserting breathing tubes and suctioning secretions—become potential sources of exposure.

Historically, significant percentages of secondary infections occur among hospital staff. They return home and infect families. They become victims of their own dedication. This is the human cost that statistics don’t capture.

The Masking Effect

A troubling theory circulates among epidemiologists. Over recent years, the world’s obsession with COVID-19 may have inadvertently hidden MERS. Healthcare systems were overwhelmed. Testing protocols were narrowly focused.

If a patient presented with respiratory symptoms, they were tested for SARS-CoV-2. If negative, they went home without further investigation.

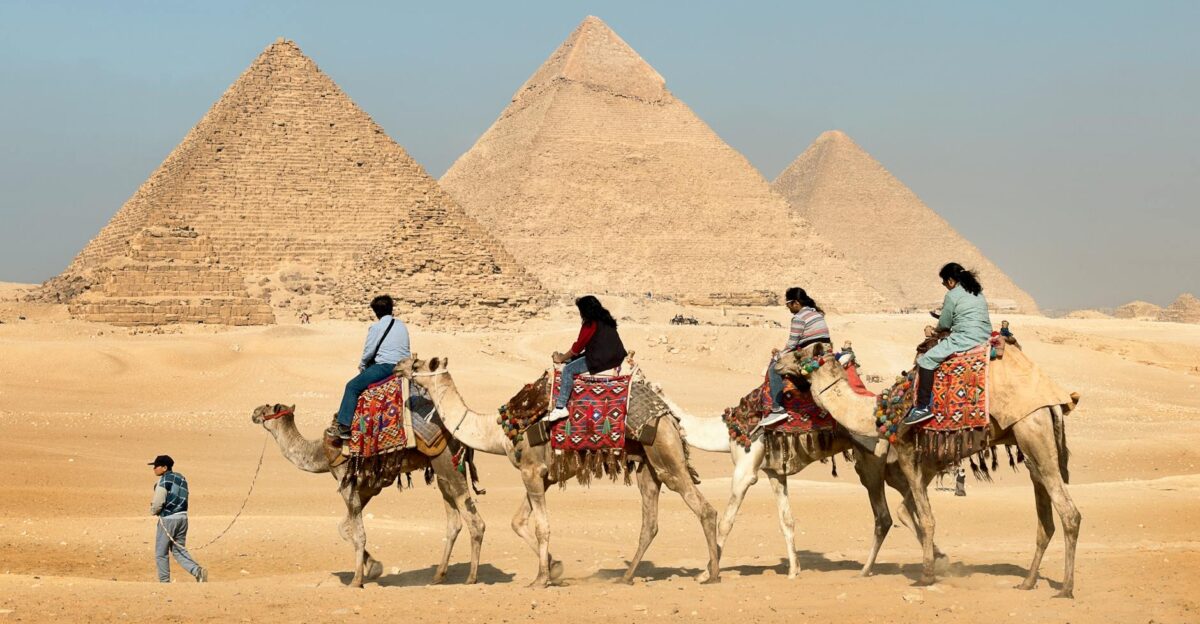

A Plane Ride Away

Modern life is a vector for disease. Every day, thousands cross borders carrying their belongings and viruses. Flights from Saudi Arabia operate to destinations in Europe, the United States, and Asia. Religious pilgrimages bring millions of visitors. Business travelers move between continents.

These networks of human connection, which define our globalized world, are also networks of disease transmission.

A Moderate But Persistent Risk

The World Health Organization labels the current risk as “moderate” globally. This classification offers comfort but masks the uncomfortable truth. A moderate risk from a highly lethal pathogen is still a threat worth taking seriously.

The virus continues to circulate in animal reservoirs, with spillover events occurring regularly. As long as camels carry the virus and humans interact with them, new human infections will continue to occur.

Understanding The Case Fatality Rate

One in three. That’s the brutal math of MERS. Of every 100 people confirmed infected, 37 will likely die. In Saudi Arabia, the rate climbs to 39%. Seasonal flu kills roughly 0.1% of those infected. Even COVID-19 was significantly less lethal.

MERS exists in a category of danger reserved for diseases like rabies or Ebola. Yet this knowledge hasn’t mobilized the world. The virus remains underfunded and under-prepared-for.

Why Vigilance Remains Critical

The return of MERS to France is a test—not of the virus, but of us. Can healthcare systems maintain awareness of rare threats? Can doctors remember to ask about travel history when exhausted? Can public health infrastructure stay alert when stretched thin?

Early identification and rapid isolation are the only tools available to prevent one imported case from becoming the next cluster.

A Wake-Up Call For Europe

Two cases in France. A virus that kills one in three. No vaccine. No cure. Twelve years of persistence. The World Health Organization warned on December 24, 2025, that MERS “continues to pose a threat in countries where it is circulating in dromedary camels, with regular spillover into the human population.”

Europe faces a choice: treat this return as a warning to be heeded, or as a curiosity to be forgotten. The virus, meanwhile, continues its quiet work.

Sources:

World Health Organization, “Disease Outbreak Investigation: MERS-CoV Cases in France,” December 24, 2025

World Health Organization, “Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Global Summary,” December 21, 2025

French Public Health Authority, “Confirmation of Two MERS-CoV Cases – Travel-Associated,” Early December 2025

World Health Organization, “MERS-CoV Zoonotic Transmission and Dromedary Camel Circulation Report,” 2025

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “MERS-CoV Case Fatality Rate Analysis: 2012–2025 Global Data”

South Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare, “2015 MERS Outbreak Investigation Report: 186 Cases, 38 Deaths”