On December 4, 2025, millions of phones across California and Nevada flashed with an alarming earthquake warning: a magnitude 5.9 tremor, imminent and powerful.

Emergency dispatch centers sprang into action, and social media erupted with panic. But within an hour, a shocking discovery: the earthquake never happened. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) had issued a false alarm—the first of its kind since the ShakeAlert system’s launch.

A False Alarm Across an Unprecedented Range

The earthquake alert spread far beyond the supposed epicenter, reaching residents in San Francisco—more than 200 miles away.

In Nevada, officials in Carson City and Lyon County immediately activated emergency protocols, preparing for a potential disaster that never came. Panic swirled as local 911 centers received countless calls from residents fearing the worst.

ShakeAlert’s Impressive Track Record

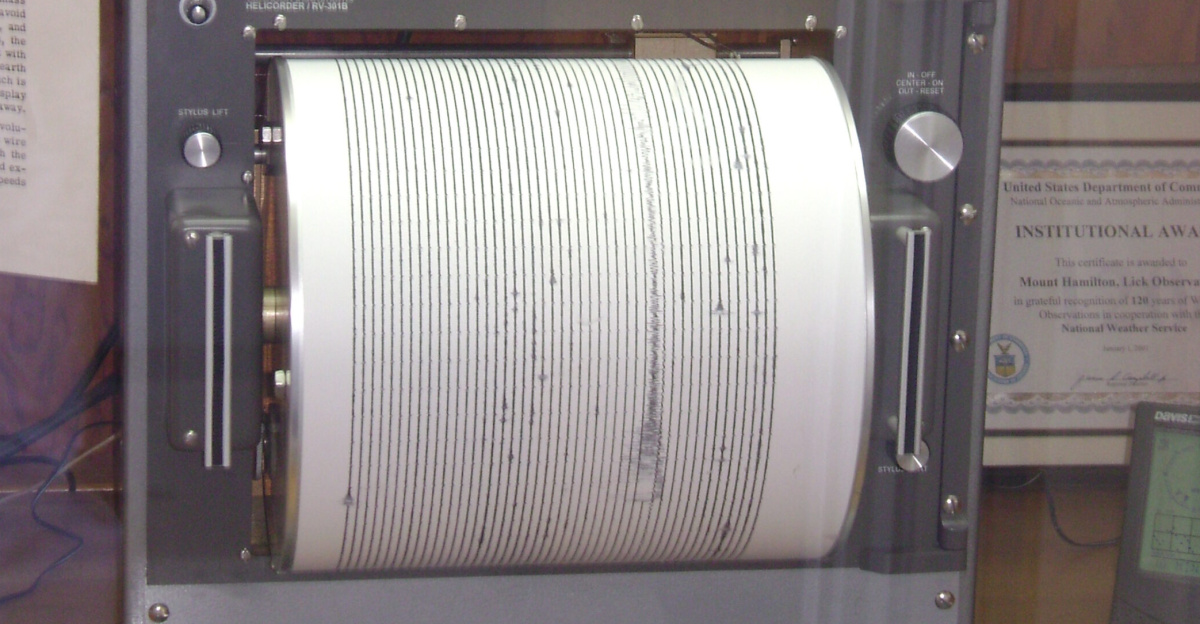

ShakeAlert, the earthquake early warning system, had been a symbol of hope. Since its launch in 2019, it had issued over 170 accurate alerts with no false positives.

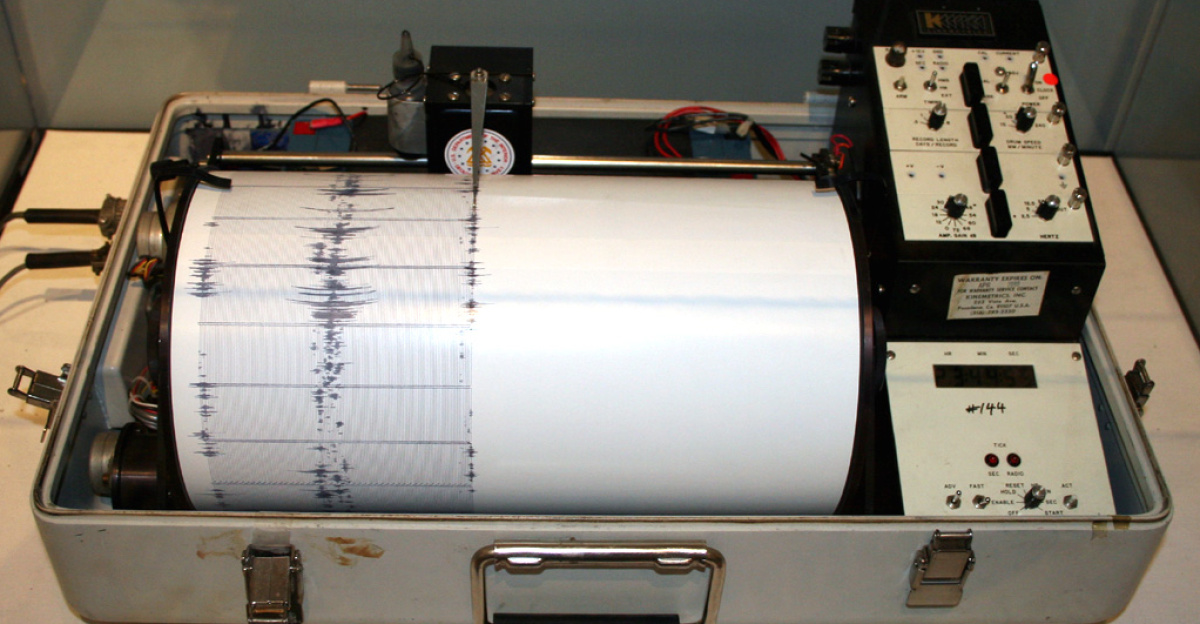

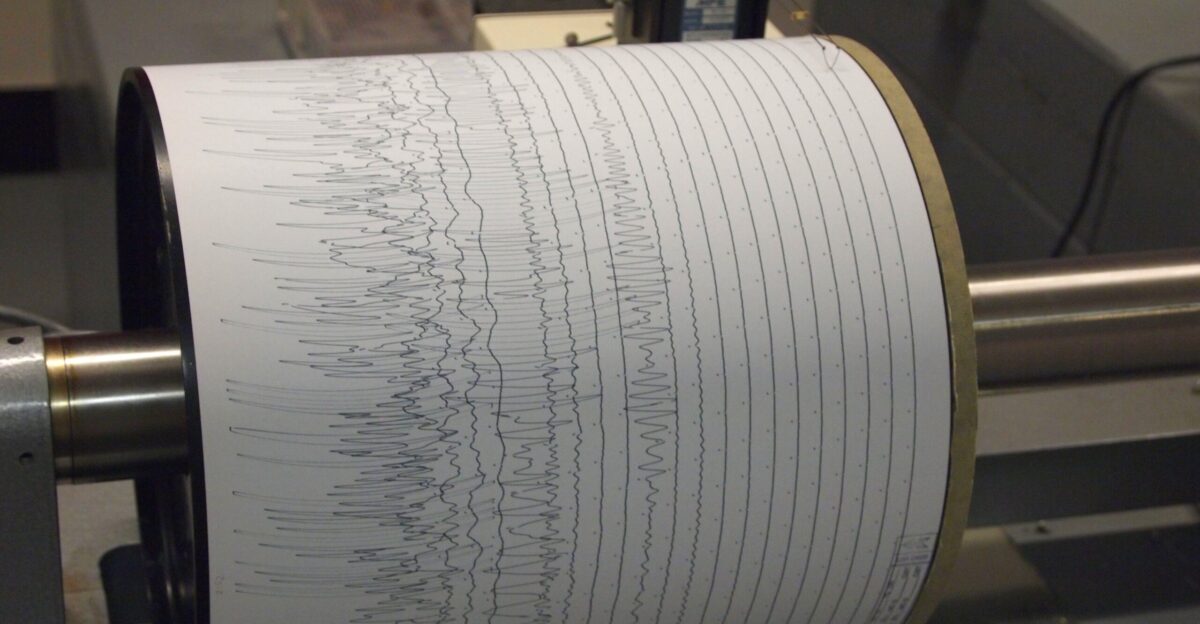

This cutting-edge system, built with data from over 1,700 seismometers across California, Oregon, and Washington, had gained the trust of millions. But on December 4, the system faltered, delivering a false alarm of catastrophic proportions.

Pressure on the System

To enhance the system’s sensitivity, the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network expanded its monitoring to detect even the smallest tremors.

The region, vulnerable to the Cascadia Subduction Zone fault, required heightened surveillance. But this increased sensitivity came with risks: errors and data anomalies, like the one that triggered the December 4 alert.

The Faulty Earthquake Detection

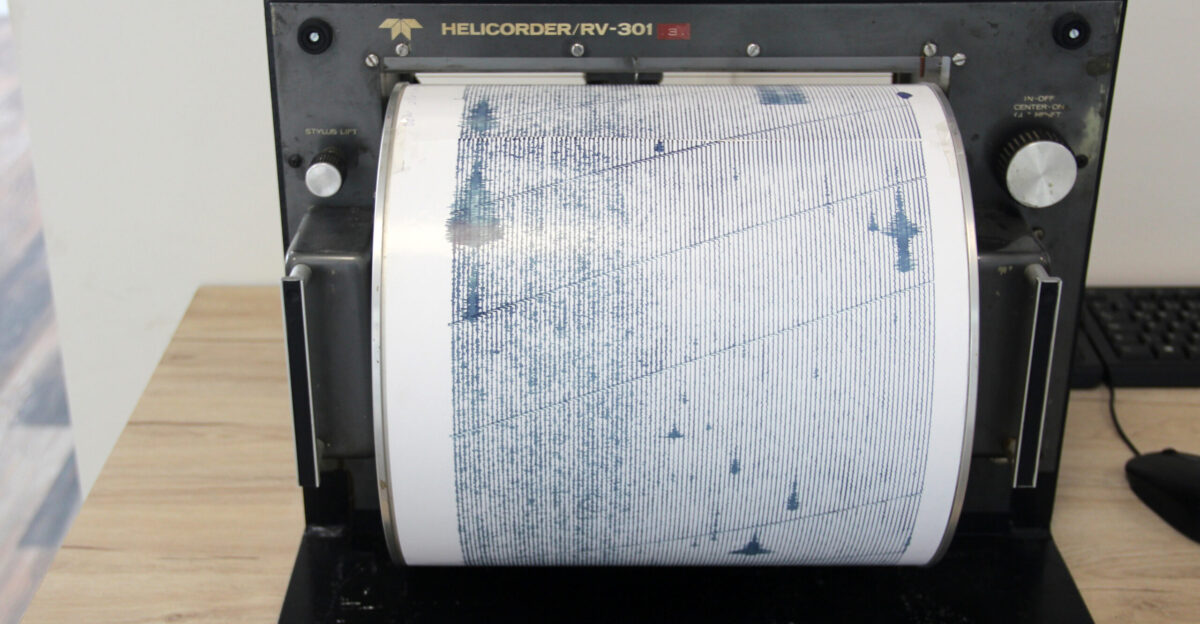

At 8:06 a.m. local time, the ShakeAlert system detected what appeared to be a magnitude 5.9 earthquake near Dayton, Nevada. Four seismic stations recorded shaking, triggering the alert.

Within seconds, millions received the warning. But within an hour, USGS officials confirmed: no earthquake had occurred. It was a false alarm—an unprecedented mistake in the history of ShakeAlert.

The Culprit—Faulty Data Transmission

USGS scientists quickly pinpointed the problem: faulty data from Nevada’s seismometers. The algorithm, designed to detect earthquakes, misinterpreted the erroneous signals as an actual quake.

Angie Lux, an earthquake scientist at UC Berkeley, described the error as the result of faulty sensor data—a glitch that caused the system to issue an alert for a non-existent event.

Panic Grips Local Communities

In Carson City, emergency management teams had already begun preparing for a disaster. At the Nevada Seismological Laboratory, scientists felt no shaking—there was nothing to indicate an earthquake.

Yet, residents in Lyon County flooded 911 operators with calls. The panic was real, but the quake was not.

Investigations Begin

In the aftermath, Congress quickly demanded answers. Five California representatives, led by Rep. Kevin Mullin, sent a formal letter to USGS, questioning why multiple seismic stations had reported false shaking and how such a critical system could fail.

The letter highlighted a growing concern: false alarms erode public trust, and in emergencies, seconds matter.

The Early Days of ShakeAlert

ShakeAlert had been in operation for nearly six years before the December 4 incident. Its track record was strong—170 successful alerts and a handful of false positives, mostly in remote areas.

In the years leading up to the incident, ShakeAlert had proven itself a vital tool for saving lives in earthquake-prone regions.

The Cascade Subduction Zone—A Major Threat

The December 4 alert’s failure highlights the challenges posed by the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ), one of the most dangerous fault lines in North America.

The region’s vulnerability to a potential 9.0-magnitude earthquake, along with its potential for a 100-foot tsunami, emphasizes the critical need for accurate warning systems. But the December incident raises questions about their reliability.

The March 2025 Precedent

The false alarm in December 2025 wasn’t the first time ShakeAlert had caused confusion. Back in March 2025, a 4.6 magnitude earthquake near San Diego was initially misclassified as a much stronger tremor.

Despite efforts to fix the system, the two incidents in less than a year have sparked doubts about the accuracy of automated alerts.

Speed vs. Accuracy

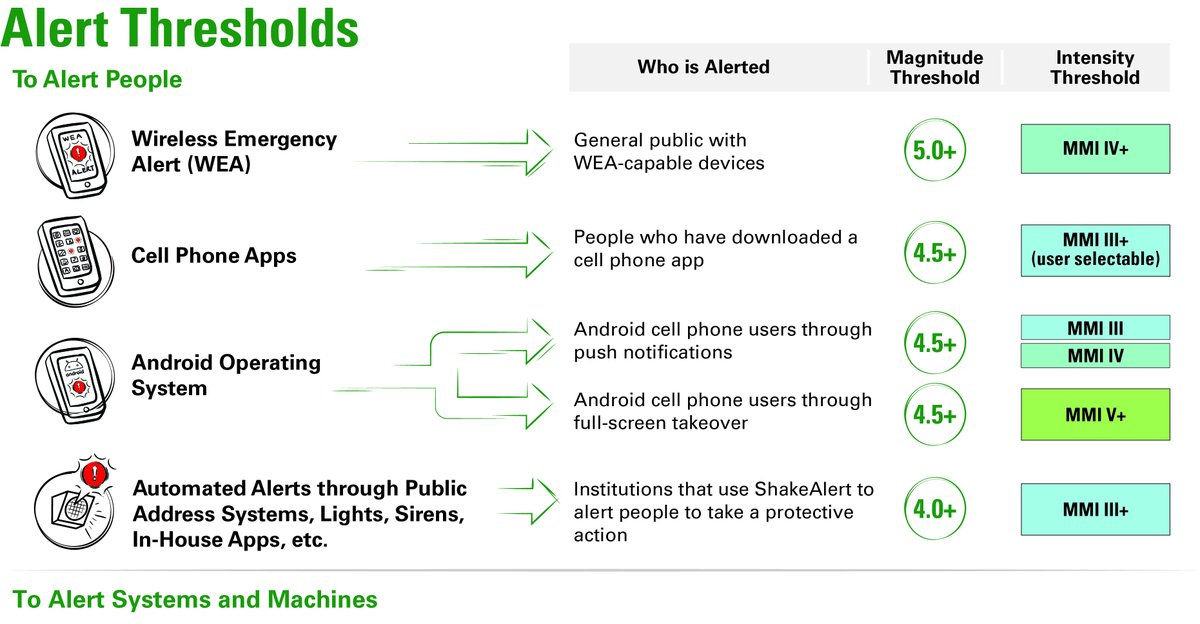

ShakeAlert was designed to prioritize speed. Alerts were issued at a magnitude threshold of 4.5—below the typical damage threshold.

While this meant fewer earthquakes were missed, it also meant more false alarms. Scientists and emergency managers acknowledged this trade-off: speed saves lives, but it can also cause unnecessary panic.

Institutional Response to the False Alarm

Once the false alarm was confirmed, USGS acted swiftly. Within one hour, officials issued a public statement acknowledging the error.

The rapid response was a stark contrast to the usual defensive posture of many government agencies. USGS’s transparency was seen as a positive move, helping maintain public trust despite the blunder.

A Closer Look at the Algorithm

USGS scientists worked overnight to correct the faulty sensor data that triggered the false alarm. The problem lay in the algorithm’s ability to differentiate between actual earthquakes and sensor errors.

The incident has led to calls for algorithmic improvements to prevent future misclassifications and ensure the accuracy of future alerts.

Restoring Confidence

ShakeAlert’s future depends on its ability to rebuild public trust. While false alarms will never be entirely eliminated, clearer communication about the system’s limitations and potential risks could help mitigate public skepticism.

Ultimately, the lesson from December 4, 2025, is that the balance between speed and accuracy in early warning systems is delicate—and must be carefully managed to save lives without causing undue panic.

Sources:

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) ShakeAlert System Official Reports: “ShakeAlert System and the December 2025 False Alarm” December 2025

Pacific Northwest Seismic Network (PNSN) Reports: “Seismic Event Detection: M2.3 Explosion in Diablo, Washington” December 14, 2025

California Seismic Safety Commission (CSSC) Reports: “ShakeAlert’s Performance and Public Response: A Review of 2025 Incidents” December 2025

Congressional Hearings and Letters (Rep. Kevin Mullin): “Letter to USGS Regarding December 2025 False Alarm” December 2025

News Outlets: New York Times, KCRA 3 (California): “Millions Receive False Earthquake Alert in California and Nevada” December 4, 2025

Seismology and Earthquake Science Journals: “Challenges in Earthquake Early Warning Systems: The 2025 ShakeAlert Failure” December 2025