In August 2025, the Trump administration suddenly ordered U.S. naval and air forces into the southern Caribbean, citing rising instability.

Defense officials confirmed on Aug 14 that ships, aircraft, and other assets would be sent “to address threats from Latin American drug cartels”.

This Caribbean buildup – the largest in years – caught regional leaders off guard.

Officials warn it is meant to deter smuggling and sanctuary for criminal gangs, but details are sparse. Locals and analysts alike are now watching closely, sensing that more dramatic moves may follow.

Rising Stakes

Recent weeks saw a sharp uptick in security incidents across the Caribbean. Government reports and media describe more narco-trafficking seizures, armed skirmishes at sea, and even claims of pirates operating off Venezuela and Haiti.

Longtime observers say these events are not isolated – they reflect an emboldened organized-crime network spilling over national borders.

The U.S. government views this trend as a direct threat to American interests.

As one U.S. official put it, the deployments are explicitly designed to counter foreign drug gangs menacing U.S. security.

Handoff Zone

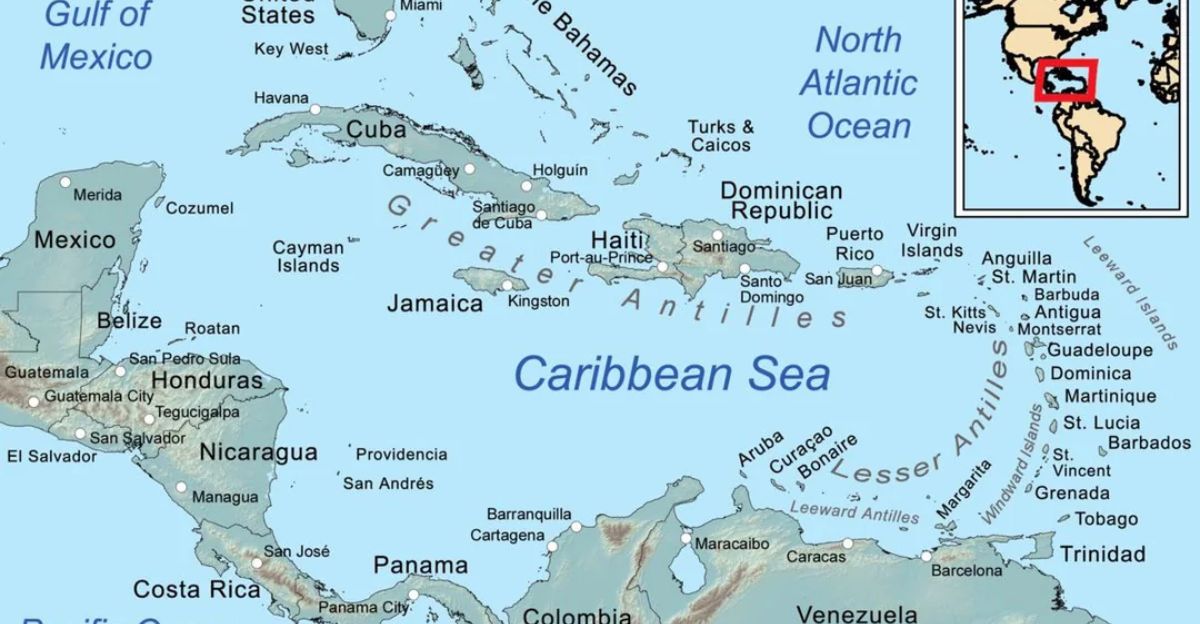

The Caribbean Sea has long been a critical transit zone for drugs and shipping. It links cocaine routes from South America to markets in Europe and the U.S. For decades, the U.S.

Southern Command (Southcom) – based in Miami – has worked with Caribbean navies and coast guards on counternarcotics.

Southcom routinely coordinates combined patrols, intelligence sharing, and training exercises in these waters.

The new deployment builds on that history: CNN reported the Iwo Jima Expeditionary Group is joining Southcom forces, noting it “is part of a broader repositioning of military assets to [Southcom]”. The U.S. is reinforcing the long-recognized role of the Caribbean as a key security “handoff” area.

Pressure Builds

The decision follows mounting regional pressure. In recent months, Caribbean governments have reported record drug hauls – multiple multi-ton cocaine busts by local and U.S. authorities – and even armed clashes over maritime boundaries.

Commercial ports and oil facilities have become flashpoints: tanker routes near Venezuela and Guyana were briefly interrupted by naval skirmishes.

Officials told Reuters that these issues are now part of a broader agenda: the administration says cracking down on cartels is “part of a wider effort to limit migration and secure the U.S. southern border”

Washington feels compelled to act as spillover from crime threatens infrastructure and stability in partner countries.

Major Deployment

On August 15, 2025, the U.S. put real weight behind the warnings. CNN reported the Navy’s Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group (three ships) and the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit (totaling over 4,000 Marines and sailors) were sent into the region.

This move – confirmed in part by U.S. officials – marked the largest U.S. military deployment in the Caribbean in years. It included destroyers, patrol helicopters, and even a nuclear-powered attack submarine.

As one anonymous U.S. source told Reuters, “This deployment is aimed at addressing threats to U.S. national security from specially designated narco-terrorist organizations in the region”.

Residents from Trinidad to Colombia watched warships converge, and commentators called it a dramatic “show of force” against the cartels.

Regional Focus

The U.S. says this buildup targets what it calls “narco-terrorist” networks and comes just as tensions around Venezuela’s oil-rich claim in Guyana are flaring. U.S. officials publicly link the two issues.

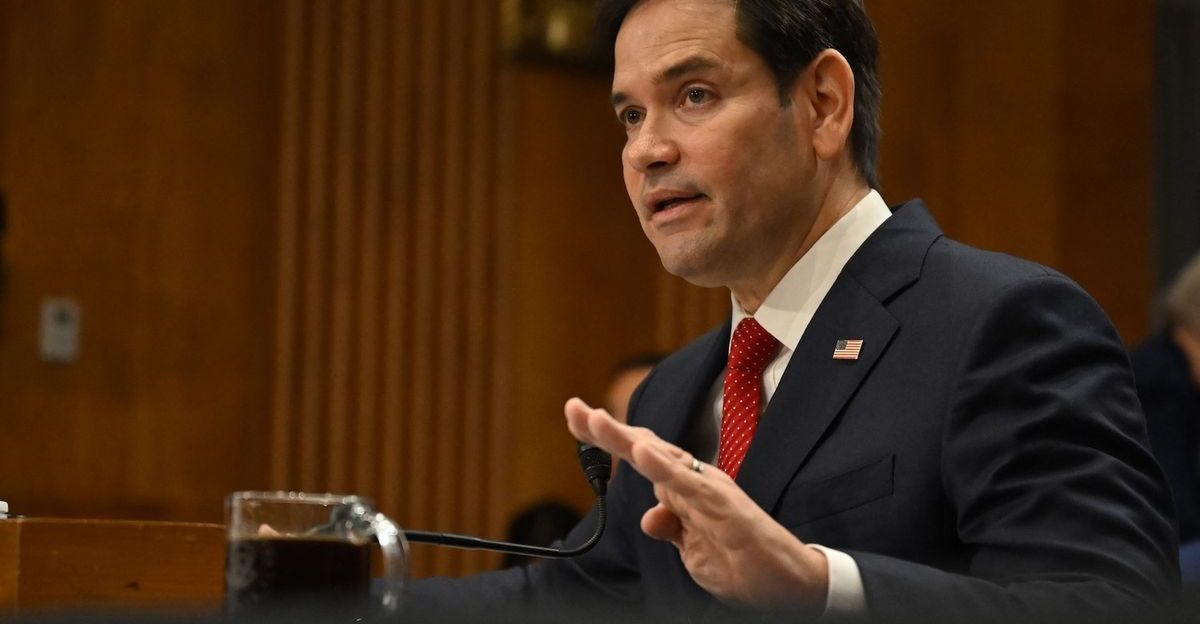

State Department tweets and Pentagon briefings emphasize cracking down on drug networks—especially those tied to Venezuela’s Maduro government.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio put it bluntly: the “Maduro regime is not a government… it is a criminal enterprise” now threatening U.S. oil firms operating lawfully in Guyana.

American policy-makers see dual challenges in the Southern Caribbean – hitting drug gangs and backing allies worried about Venezuelan aggression.

Human Lens

For ordinary people in coastal towns, the change is stark. Fishing captains in Trinidad report seeing dozens of naval vessels and surveillance planes in waters where they usually only see freighters.

“It’s the most activity I’ve seen in 30 years,” one veteran fisherman said, eyeing an incoming destroyer.

In Guyanese and Colombian ports, commerce officials note an uptick in patrols alongside shipments.

The U.S. media spotlight and military presence have left residents feeling a mix of fear and hope: anxious about accidents or incidents at sea, but hopeful that the crackdown will finally curb smuggling, which has driven up local crime.

Competitors React

The deployment has shaken up regional players. In Caracas, Venezuelan officials denounced the U.S. move as a provocation. Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello even announced Venezuela had redeployed its own patrols, declaring “the Caribbean … belongs to us”.

Foreign Minister Yvan Gil slammed the buildup as a “crude political propaganda operation” by Washington.

Meanwhile, Latin American crime groups are adapting. Intelligence reports suggest some cartels are shifting shipments further south or trying alternative routes.

Countries in the region – from Colombia to the Dominican Republic – have quietly stepped up joint patrols to avoid being caught unprepared.

Macro Context

This Caribbean surge fits into a wider strategy. Earlier in 2025, the U.S. formally labeled major drug gangs like Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel and Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua as “global terrorist organizations”.

That unprecedented move allows military and financial tools that traditionally applied only to Islamist or insurgent enemies. By this logic, the administration justifies direct force overseas against criminal networks.

It means the Caribbean deployment is not just counter-narcotics, but part of a new hybrid “counternarcotics-as-counterterrorism” campaign.

Critics say it blurs old categories, but supporters argue it reflects reality: powerful cartels are now seen as existential threats to U.S. security.

Submarine

Perhaps the boldest symbol of the surge is the submarine. A nuclear-powered attack sub is now reportedly patrolling Caribbean waters alongside surface warships.

U.S. subs rarely surface in this region, so many analysts see it as unprecedented. It sends a clear signal: the U.S. is willing to use top-tier assets to hunt traffickers.

A defense expert noted that adding a sub marks “an extraordinary commitment to force projection.” Its crews can covertly gather intelligence and, if ordered, launch strikes from beneath the waves.

For smugglers and adversaries, the sub’s presence is both a surprise and a warning that American reach now runs under the surface of the Caribbean.

Stakeholder Friction

Not all U.S. planners agree on the deployment’s execution. Several defense officials privately questioned the Marines’ role: few infantry are trained for counternarcotics, and some see the mission more in the Coast Guard or the DEA’s wheelhouse.

CNN reported that one U.S. official warned the troops would have to “lean heavily on the Coast Guard” to make arrests and seizures.

Coast Guard leaders themselves caution that diverting resources overseas could leave the U.S. border thinner.

They argue military muscle must be balanced by law enforcement and development aid ashore. In Washington, this has become a familiar debate: how far can hardware go in solving problems rooted in poverty and weak justice systems?

New Leadership

The operation is under U.S. Southern Command, led by Admiral John D. “D.J.” Smith. A career naval aviator and former task-force commander, Smith took charge of Southcom earlier in 2025.

He has emphasized working closely with partner nations. In recent months, he hosted Caribbean chiefs of naval and coast-guard staffs in Miami and expanded joint exercises like UNITAS.

His doctrine stresses “rapid crisis response” and integrated planning – an approach now being tested.

Behind the scenes, Southcom is coordinating with homeland security and regional agencies to synchronize tracking of suspect vessels and aircraft.

Comeback Efforts

To shore up gaps, the Pentagon is mobilizing other assets. The U.S. Coast Guard has deployed extra cutters and P-3 maritime patrol planes to the region.

Training programs with Latin American navies and police have been accelerated: for example, Guyana and Trinidad deployed forces last month in a joint interdiction drill.

U.S. intelligence teams have been dispatched to Caribbean hubs to link up radar and satellite data across borders. All this aims to make the massive ship deployment effective by ensuring there are good leads on cartel movements and ready interceptors on hand.

The hope is that combining high-tech surveillance with local law enforcement will squeeze traffickers from above and below.

Expert Doubts

Many analysts caution that ships alone won’t fix the underlying problems. Latin America experts point out that corruption, poverty, and weak institutions drive the drug trade – factors a fleet cannot cure.

“More ships won’t solve the root problems,” says one regional security analyst. Similar critiques have surfaced in Congress, where some lawmakers ask why billions in aid to Central America (for crime prevention and development) are still needed if military force is the answer.

Others note historical lessons: past U.S. interventions in Panama or Colombia quelled violence only temporarily unless governance also improved.

Skeptics warn that militarizing the Caribbean won’t eliminate the demand or poverty that fuels the illicit flows.

Looking Forward

As the naval task force settles in, big questions remain. Is this an emergency surge or the start of a long-term presence? U.S. officials have given mixed signals. Some Pentagon briefings suggest the mission could last “several months,” while others imply this is a short-term exercise. Congressional leaders are pushing for clarity.

Meanwhile, U.S. planners say they may need to rotate in fresh units or expand the mission if needed. Most agree on one thing: vigilance must continue.

Even after the warships leave, the pull of drug profits and political turmoil in the region will not vanish overnight.

Washington is now bracing for an evolving campaign, not just a one-off show of force.

Political Fallout

The buildup has deep political consequences. Venezuela and its regional allies have condemned it as interference. Caracas portrays itself as defending national sovereignty, while diplomats accuse Washington of stoking anti-American sentiment.

Guyana’s government, on the other hand, has privately welcomed the security boost.

Facing Venezuela’s long-standing claim on Essequibo (a resource-rich region), Georgetown sees U.S. support as insurance. In practice, smaller Caribbean states have largely stayed neutral in public, but informally many have thanked the U.S. for its help against the transnational gangs.

The result is a sharpened divide: U.S. ties with Guyana and Colombia are tightening, even as relations with Caracas and Havana worsen.

Global Ripples

Even distant governments are watching the Caribbean. The UK and Canada have offered limited help – mostly intelligence sharing and port inspections – while Brazil has quietly ramped up border patrols in its Amazon region.

International trading firms are taking note: some shipping lines say they may reroute vessels to avoid any “hotspots” off Venezuela or in southern waters.

In financial markets, oil traders have briefly spiked up Guyana crude prices out of concern over the geopolitical friction. Beyond the hemisphere, China and Russia have rhetorically criticized the move, but offered no practical counter.

For global actors, the U.S. deployment is a reminder that Latin American security is once again center-stage.

Legal Questions

The military surge also raises thorny legal issues. By branding cartels as terrorist organizations, the U.S. effectively allows armed force where it previously relied on police.

Lawmakers and lawyers are debating what this means for international law: U.S. troops have generally needed host-nation permission or an imminent threat to operate on the high seas.

Some argue that Congress should update the laws governing counternarcotics to explicitly authorize such missions.

Others worry that blending anti-drug and counter-terror powers could set a precedent – what prevents future presidents from using force against, say, major cybercrime rings?

The administration is forging new ground, and Washington’s courts and allies are watching for the limits of this approach.

Shifting Norms

The Caribbean deployment comes as U.S. intervention attitudes are in flux. Polls in Latin America show divided views: many Colombians and Central Americans, battered by violence, support tough U.S.-backed action against cartels.

But others, from Mexico to Chile, remember past U.S. operations (like Panama 1989 or Iraq 2003) and warn against overreach.

In the U.S., some lawmakers applaud the muscular stance, while human-rights groups caution it could destabilize fragile democracies.

Regional media outlets debate whether we are seeing a return to Cold War–style interventions or merely a one-off campaign.

Reflections

The U.S. military surge in the Caribbean signals a new era of assertive intervention in the Western Hemisphere. It reflects Washington’s deep anxiety about crime and migration – and a determination to be seen as tough on threats.

But it also highlights how American strategy is changing: instead of boots on the ground, the emphasis is on naval power and “over-the-horizon” tactics.

Local experts note it is a historic pivot. The long-term effects are still unknown: will it deter cartels or simply push them deeper?

One U.S. analyst says this move underscores President Trump’s focus on security issues, calling cartel violence “a central goal” of his administration.