The room fell silent as Sweden Democrats leader Jimmie Åkesson leaned toward the microphone. Cameras flashed. “Everything should be on the table,” he said — pausing just long enough for the weight of it to register. Nuclear weapons. In Stockholm’s Parliament, a taboo older than most lawmakers had just been shattered.

For a nation that once shipped away its last plutonium in 2012, the question was unthinkable: Could Sweden build the bomb after all?

The Spark: “Everything Should Be on the Table”

Sweden Democrats leader Jimmie Åkesson stunned observers by declaring that “everything should be on the table” — including nuclear weapons.

His remark shattered a long-held taboo, forcing even establishment voices to respond. What was once unthinkable is now being publicly debated in parliament and policy circles, echoing Sweden’s forgotten Cold War ambitions.

A Chilling Endorsement from Within

Åkesson wasn’t alone. Robert Dalsjö of the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI) said, “Now we must discuss independent nuclear weapons with a Swedish component.”

The statement came from a top defense strategist, not a fringe voice — suggesting this isn’t political theater. It’s a signal that serious figures inside Sweden’s security establishment see deterrence differently now.

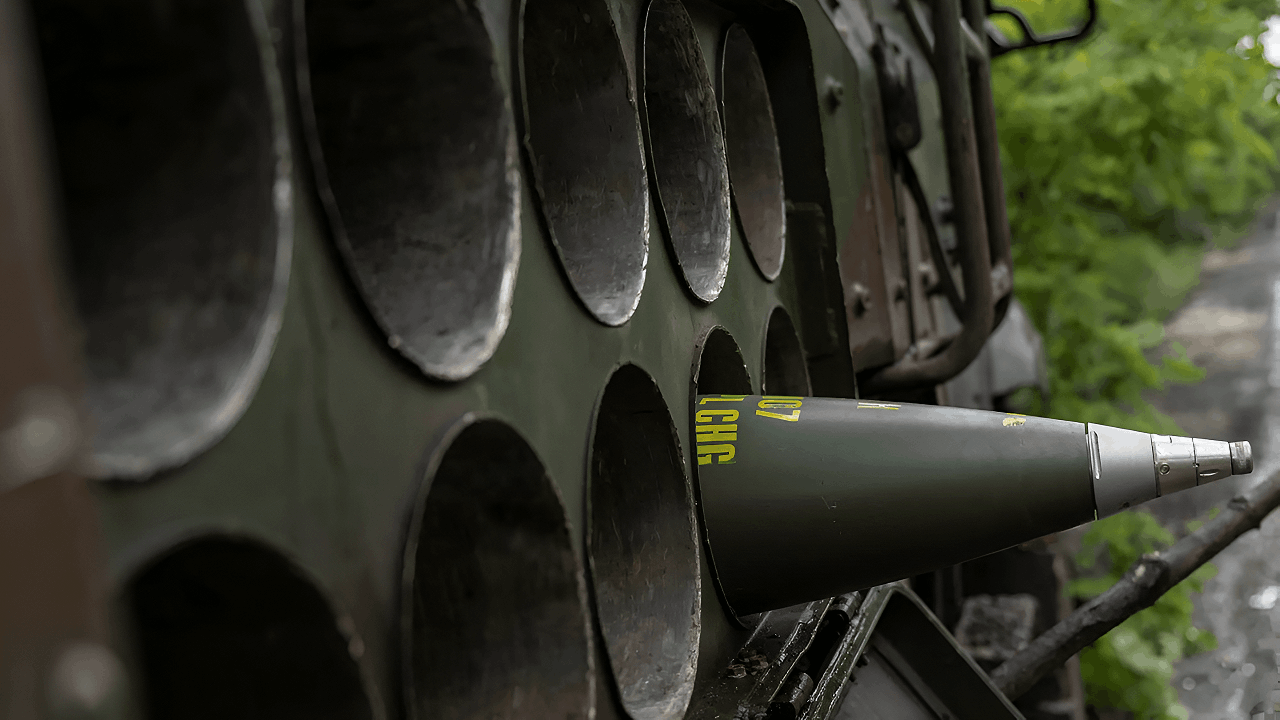

Drones Over Europe Raise the Stakes

The nuclear talk didn’t happen in a vacuum. Unmanned drones have recently violated European airspace at alarming rates. Denmark shut down parts of Copenhagen Airport after repeated sightings.

Poland reported multiple incursions. NATO jets were scrambled. The message seems clear: Russian or proxy forces are testing Western resolve — and Sweden, fresh in NATO, is a prime target.

Why Sweden’s Geography Makes It Vulnerable

Positioned between the Arctic and the Baltic, Sweden is both a NATO gateway and a front-line observer of Russian military behavior.

Its long, exposed coastline and critical infrastructure make it strategically vital — and difficult to defend. The renewed nuclear debate reflects anxiety that collective defense may not be enough if the nuclear balance tilts further east.

A Nation Once Months from the Bomb

Declassified archives reveal a startling truth: Sweden came within six months of a working nuclear weapon in the 1960s. Its research program, backed by advanced reactor technology, had “most of the bomb already built” by 1965.

Political leaders halted it only at the last moment — choosing moral leadership over deterrence. Today, that history feels uncomfortably relevant again.

The Great Pivot: From NPT Hero to Hypothetical Rebel

In 1968, Sweden signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and dismantled its weapons program. By 2012, it even shipped the last remnants of its plutonium to the U.S., erasing its bomb-making capacity.

To reverse that now — even hypothetically — would mark an unprecedented shift for a European Union member and longtime champion of disarmament.

How Fast Could Sweden Do It Again?

Experts at FOI caution that rearming would take 10–15 years. The Cold War engineers are gone, the facilities dismantled, and the fuel-cycle infrastructure nonexistent.

Building even a “minimum deterrent” of 20–50 warheads would require tens of billions in investment and a decade of focused effort — a vast industrial revival under military secrecy.

What the 1960s Taught Sweden

Back then, Sweden’s scientists built small reactors designed for both civilian and weapons purposes — a dual-use pathway. Their quiet success alarmed Western allies, who feared an independent Nordic nuclear power.

That legacy still haunts Swedish policy: the technical prowess remains part of its national pride, even if the will to weaponize it was buried for half a century.

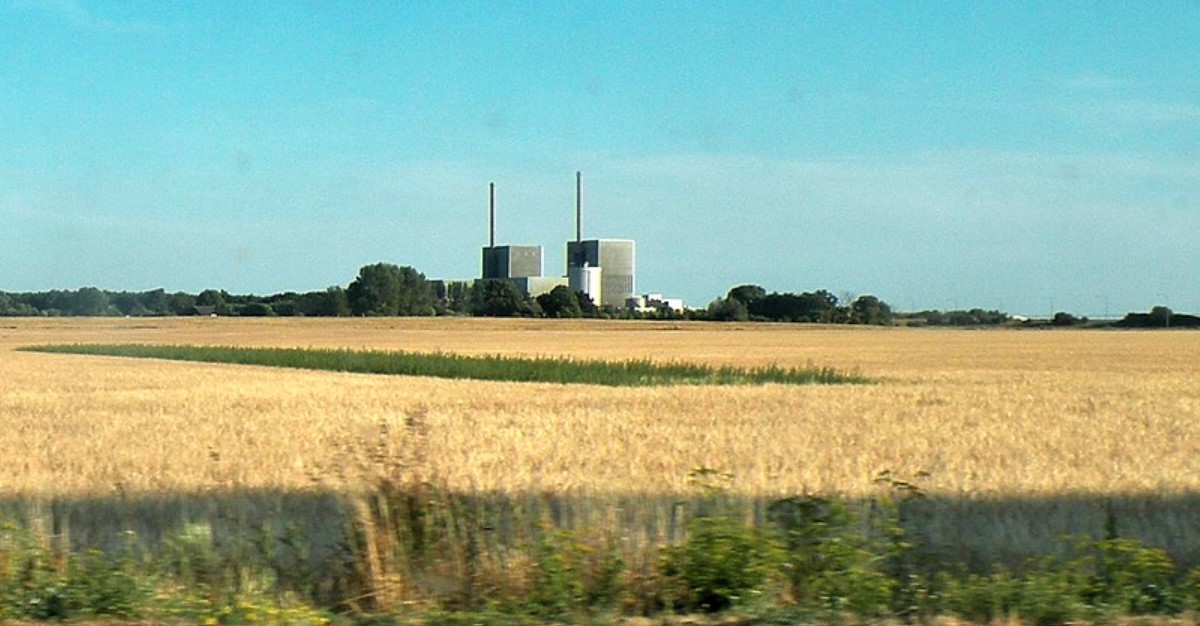

The Energy Shift That Reopened the Door

The nuclear conversation re-emerged after Parliament lifted Sweden’s remaining restrictions on new reactors in November 2023, ending a 43-year policy that began after the 1980 referendum and was partially modified in 2010.

The policy reversal was driven by both energy insecurity and Russian aggression. Suddenly, nuclear technology was back — first as power, now as potential protection. The boundary between the two has blurred faster than anyone expected.

Powering Up: The New Nuclear Roadmap

Sweden’s government plans to build two new reactors by 2035 and up to ten by 2045, supported by $23 billion in state-backed loans.

Officials argue this expansion will stabilize prices, strengthen resilience, and reduce dependence on foreign energy. But strategically, the same expertise that fuels new power stations could also reignite nuclear weapons capability — intentionally or not.

From “100% Renewable” to “100% Fossil-Free”

By replacing the target of “100% renewable” electricity with “100% fossil-free,” Sweden officially brought nuclear energy back into the fold.

That semantic shift may seem minor, but it reflects a deeper philosophical change: pragmatism over idealism. As global threats rise, Sweden’s energy identity is now inseparable from its defense posture.

Industry and Innovation Surge Forward

Major utility Vattenfall and private investors are racing to capitalize on the government’s new pro-nuclear stance. Engineering firms, construction companies, and universities are reviving dormant expertise.

Thousands of skilled jobs are expected. The economic case is strong — but so is the geopolitical symbolism: Sweden is rebuilding the technical backbone once used to craft a bomb.

Fear, Deterrence, and National Psychology

To many Swedes, the new rhetoric isn’t about aggression — it’s about survival. In a Europe where Russian threats are increasingly nuclear, reliance on NATO’s umbrella feels uncertain.

Public debate now turns on an existential question: can true neutrality still exist in a nuclear world? Or must Sweden reclaim control over its ultimate deterrent?

Europe’s Nuclear Taboo Begins to Crack

For decades, European nations outsourced nuclear deterrence to the U.S., U.K., and France. Sweden’s recent comments mark the first serious break in that consensus.

If even Stockholm — symbol of humanitarian diplomacy — is reconsidering the bomb, others may follow. Analysts warn this could trigger a psychological chain reaction across Europe’s security architecture.

Global Context: 12,200 Warheads, 2 Superpowers

Today, nearly 12,200 nuclear warheads exist worldwide. Roughly 90% are controlled by just two nations: Russia and the United States.

As smaller states rethink deterrence, global non-proliferation norms face new stress tests. Sweden’s debate may be small in scale — but symbolically, it challenges the world’s fragile balance of nuclear trust.

The Experts’ Cautionary Voices

Not everyone supports the idea. FOI expert Martin Goliath warns that weaponization would be “a very large industrial project,” likely consuming resources better used for defense and infrastructure.

Critics argue that NATO membership already offers nuclear protection — and that pursuing an independent deterrent would erode Sweden’s moral and diplomatic influence.

A Clash of Identities

Sweden’s debate reveals a deeper tension: between its historic pacifist ideals and its emerging realist instincts. Younger politicians frame nuclear capability as insurance, not betrayal.

Older generations, shaped by disarmament culture, see it as a moral regression. The argument is no longer just about policy — it’s about what kind of nation Sweden wants to be.

The Clock May Already Be Ticking

Even if Sweden never builds a bomb, the decision to debate it could set a long-term process in motion. Industrial partnerships, nuclear fuel research, and advanced reactor development all shorten the timeline if deterrence becomes policy later. In security terms, the country may already be halfway down a path it insists it hasn’t chosen.

Sweden’s Nuclear Future — Power or Paradox?

Sweden now stands at a historic crossroads: renew its moral leadership or reclaim its sovereign deterrent. The choice carries enormous implications for Europe’s stability and the future of nuclear non-proliferation.

What began as an energy reform has become a moral riddle — one that asks: in an age of drones, war, and nuclear threats, can peace still be trusted to ideals alone?