Federal immigration raids in Southern California escalated dramatically in summer 2025. ICE officials report detaining over 2,200 people in Los Angeles in a single day. Community advocates describe the sweep as indiscriminate.

“People are now increasingly afraid and intimidated because of the way ICE is executing these … at such a widespread, indiscriminate and mass scale,” warned immigration attorney Greg Chen.

Critics charge the tactics relied on profiling by race, language and job. The raids sparked large protests in Los Angeles and elsewhere, foreshadowing a major legal and constitutional showdown.

Record Enforcement

By summer, the Trump administration had ordered a massive uptick in deportations. White House officials formally tripled ICE’s daily arrest target from roughly 1,000 to 3,000.

To help meet that goal, the Pentagon federalized an unprecedented force – over 4,200 California National Guard soldiers and 700 Marines – to accompany ICE in Los Angeles.

Lawmakers called it the largest deportation push in U.S. history. In practice, though, ICE struggled to hit those numbers: by late June it was averaging only about 930 arrests per day nationwide. Still, authorities insisted they would press on with aggressive sweeps in Los Angeles.

Historical Context

Such large-scale deportations have precedents. In 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower’s “Operation Wetback” used military-style raids to expel undocumented Mexican workers.

Officials at the time claimed over a million removals, but historians estimate only about 250,000 people were actually deported. That campaign was criticized for civil rights abuses and snaring U.S. citizens of Mexican descent.

Trump administration officials have explicitly cited the 1954 operation as a model for 2025 enforcement. Historians warn this linkage evokes a dark era of ethnic profiling and suggests today’s raids are part of a larger historical pattern.

Legal Challenges

Civil rights groups quickly fought back in court. On July 11, U.S. District Judge Maame Ewusi-Mensah Frimpong issued an injunction blocking ICE from stopping anyone solely because they “look[ed] Latino, speak[ed] Spanish, or appear[ed] to work a low wage job.”

The order barred arrests based solely on race, ethnicity, language, accent, location or job type.

Under the injunction, ICE arrests in the Los Angeles area plunged – data show roughly 2,800 people had been arrested by early July, but that number fell to under 1,400 after the court intervened. The administration immediately appealed, setting up a showdown over whether these tactics violate the Fourth Amendment.

Supreme Court Intervention

On September 8, the Supreme Court took up the case of Noem v. Vasquez-Perdomo. Without oral arguments, a 6–3 majority lifted the injunction on an emergency “shadow docket” order. This allowed ICE to resume stops based on broad factors, including “apparent race or ethnicity,” language, accent, location, and job type.

In a brief concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh emphasized that “apparent ethnicity alone cannot furnish reasonable suspicion; … it can be a relevant factor” when combined with other indicators. The conservative majority offered no detailed reasoning.

Justice Sotomayor, in dissent, decried the process and warned: “We should not have to live in a country where the Government can seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low wage job,” and she added, “I dissent”.

Los Angeles Impact

With the injunction lifted, ICE agents immediately redoubled raids across Southern California. Heavily armed teams fanned out through neighborhoods, industrial areas and farm towns. The Court’s order applied to seven counties (including Los Angeles and Orange) where Frimpong’s injunction had operated.

For example, the lead plaintiffs – Pedro Vasquez Perdomo and others – had been arrested at a bus stop waiting for work.

U.S. citizens were also caught up: video footage showed a Border Patrol agent pinning American resident Jason Brian Gavidia against a fence until he yelled, “I was born here in the States, East L.A., bro!” before being released. In the weeks after the decision, military vehicles appeared near Home Depot parking lots, and workers at fields and car washes reported being stopped on sight.

Personal Stories

The human toll became evident immediately. “Every Latino should be concerned…They’re allowing [federal immigration agents] to break the law,” said Alfonso Barragan, a 62-year-old U.S. citizen in East L.A. who witnessed agents tearing families from their cars.

Montebello Mayor Salvador Melendez, who is Mexican-American, condemned the operations as “racial profiling” that was “terrorizing our community”. Community activists report families staying home and workers refusing to speak Spanish in public.

These stories cut deeper than legal arguments. As Milwaukee immigrant-rights organizer Christine Neumann-Ortiz put it, “This is about due process rights and public safety for all,” when even long-term residents fear random stops.

Government Response

In Washington, DHS and the White House heralded the court’s move. “This is a win for the safety of Californians and the rule of law,” said DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin.

Officials insisted enforcement would focus on violent crime: McLaughlin promised ICE would “continue to arrest and remove the murderers, rapists, gang members, and other criminal illegal aliens” supposedly targeted by the raids.

The administration publicly stressed that any profiling would come alongside other factors, not on ethnicity alone. Still, Department spokespeople described the July injunction as having “substantially hampered” ICE’s work in L.A. – in their view, hindering the removal of dangerous criminals.

Broader Enforcement

The Los Angeles sweep is part of a nationwide crackdown. Throughout 2025, the administration has signaled ambitions to deport unprecedented numbers of immigrants. Congress has approved sharply higher budgets for ICE and border operations, and officials say they plan to use that money on raids at factories, construction sites, and trucking stops across the country.

The federal government also revived and expanded old programs: for example, the 287(g) Task Force Model – which deputizes state and local officers to enforce immigration law – has surged. Under Trump’s second term, it leapt from 135 agreements to 958 jurisdictions participating.

DHS even announced it would subsidize local police payrolls (including overtime) for jurisdictions that sign up for these programs.

Shadow Docket Concerns

Many legal experts emphasize how this case was decided. The Supreme Court used its shadow docket – an emergency fast-track process – to issue the order without full briefing or oral argument. Justice Sotomayor sharply criticized the method as “yet another grave misuse of our emergency docket”.

Lower-court judges have voiced frustration: one federal judge noted that recent emergency rulings “have not been models of clarity” and have “left many issues unresolved.”

A law professor observed that trial judges are often “left confused about what, if anything, remains in effect…because of the court’s slapdash work”.

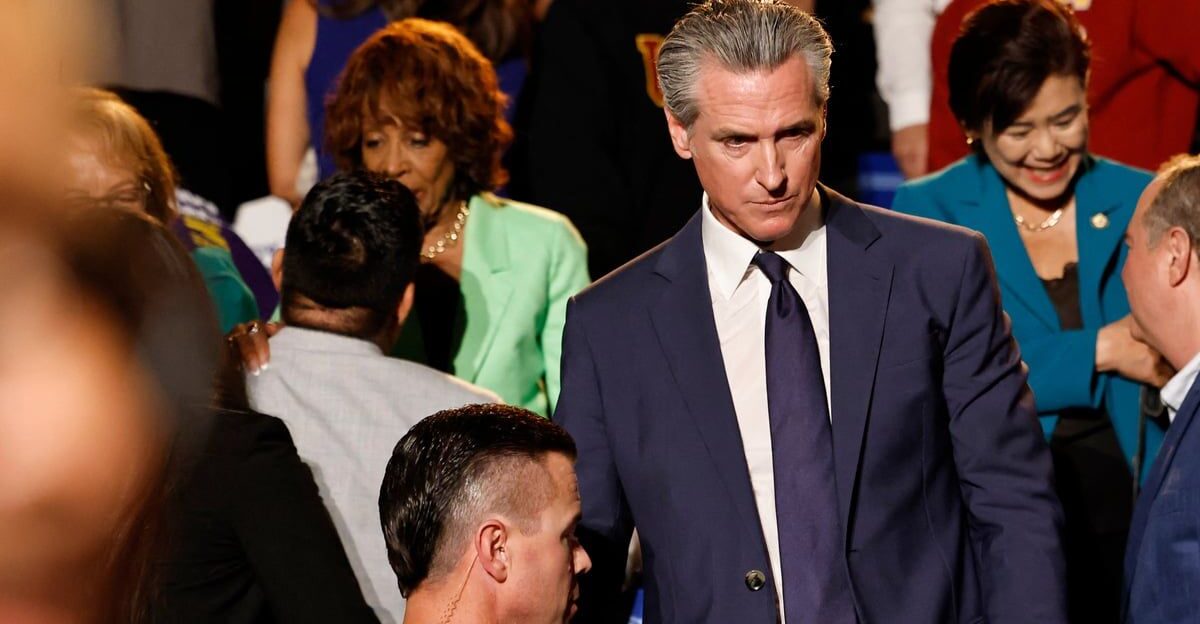

State Resistance

California’s government moved aggressively to block the federal tactics. Governor Gavin Newsom filed multiple lawsuits, accusing the Trump administration of creating “fear and terror” through a “manufactured crisis.”

In one press release he blasted the Supreme Court conservatives as having become “the grand marshal of a parade of racial terror”.

State Attorney General Rob Bonta separately sued over the use of Guard troops and Marines in L.A., calling the deployment “unnecessary and counterproductive” and asserting “there is no invasion. There is no rebellion” justifying military force. These legal challenges argue that using military assets in this way violates both the Posse Comitatus Act and state sovereignty.

Military Deployment

The militarization of the raids became a legal issue itself. In September, federal Judge Charles Breyer ruled that the large-scale Guard and Marine deployment in L.A. had violated the Posse Comitatus Act.

He found that Task Force 51’s troops engaged in forbidden law-enforcement activities, from crowd control to detaining suspects. Breyer ordered thousands of troops withdrawn.

The operation had already proved costly: Governor Newsom’s office estimated the deployment cost roughly $120 million over three months. By early September, about 2,000 of the 4,200 Guard members had been pulled out, but roughly 2,700 (the remaining guardsmen and 700 Marines) were still on duty in the area, awaiting the final resolution of the legal battles.

Enforcement Strategy

As raids continued under court scrutiny, ICE tweaked its tactics. Publicly, the agency rejected the notion of formal “quotas,” but data suggest it has shifted toward non-criminal cases to boost numbers. By late June, about 40–45% of ICE’s daily arrests nationwide involved people with no criminal charges, compared to roughly one-quarter before the intensified campaign.

Reports emerged of traffic stops and minor violations being used as pretexts for immigration enforcement. A Marshall Project analysis found that thousands deported so far have only minor offenses on record.

In court, DOJ lawyers have since insisted there is no forced quota, but sources say ICE front-line supervisors are under intense pressure to report high arrest figures. Within ICE, some veteran officers privately questioned whether the expanded dragnet makes good public-safety sense or merely fills beds.

Legal Uncertainty

Constitutional experts say the long-term legality of these tactics remains unresolved. The Supreme Court’s stay is temporary: the case will return to lower courts for full hearings. If it proceeds, judges will have to decide how the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments apply.

Some scholars point out that allowing ethnicity as a factor seems to conflict with prior Court statements that laws should be “color-blind.” Others argue that immigration law has traditionally allowed broader enforcement leeway. For now, no final rule has emerged.

The contradictory signals – race-conscious enforcement versus ostensible neutrality – highlight fundamental tensions. The issue may eventually end up back in the Supreme Court under a full briefing schedule or prompt new legislation.

Future Implications

This ruling raises fundamental questions about America’s future. President Trump has already signaled he may send the same sort of troops and agents to Chicago and other cities, saying, “We’re going in. I didn’t say when, we’re going in” to enforce immigration and public safety there.

Reports show DHS preparing to use a Great Lakes naval base near Chicago to house federal agents. DHS publicly vowed to “go to wherever these criminal illegal aliens are – including Chicago, Boston, and other cities”.

Civil rights groups worry that the Los Angeles “blueprint” will be exported: they fear police departments elsewhere may begin using ethnicity as a baseline screening tool. On a broader level, the case pits federal authority against states’ rights. California officials say sending troops and sanctioning profiling in a major city violates constitutional limits and harms trust.

Political Ramifications

The decision has already rippled through politics. Republican officials have touted it as a necessary step for border security and law enforcement, even as some opponents accuse them of encouraging bias.

Democratic lawmakers have seized on the ruling to push new checks on executive power: for example, bills have been introduced to require written opinions for emergency court orders and to explicitly bar racial profiling in immigration arrests.

These legislative proposals are likely to become debate points in the coming elections. Activists on both sides have organized rallies and campaigns around the issue. In the courts, it may influence which judges are confirmed: Senators are asking nominees whether they support race-based stops.

International Concerns

Human rights observers around the world have reacted with concern. Civil liberties organizations argue the ruling marks a step backward for U.S. constitutional norms. Some compare it to past periods of government-sanctioned discrimination.

CAIR, the Muslim civil rights group, warned that the decision gives ICE “license to profile and terrorize Latino and immigrant communities” and will endanger “the safety and well-being of millions of people—regardless of their status”.

International media have noted the irony that America, once a champion of minority rights globally, has now explicitly permitted ethnic profiling at home. Latin American governments, while diplomatically cautious, are reportedly watching closely, since many of their citizens in the U.S. could be affected.

Constitutional Questions

Legal scholars are debating the wider constitutional impact. If the Court allows ethnicity as one factor in stops, how does that square with the Equal Protection Clause? Does this decision create a narrow exception for immigration enforcement, or does it undermine the principle that the law must be “color-blind”?

Some experts note that the Court’s 2025 rulings on school admissions, for example, emphasize strictly forbidding racial preferences. Now it seems to be drawing a line between affirmative-action contexts and immigration.

There is also tension with Fourth Amendment precedent: the Constitution protects people from “unreasonable searches,” but what counts as reasonable when thousands are being rounded up en masse?

Community Impact

Across the country, Latino communities are living with heightened anxiety. Immigrant-rights groups report that more families are avoiding workplaces, schools and public events for fear of being stopped. Many neighborhood and faith leaders have launched “know your rights” workshops and opened legal hotlines.

Community organizations are fundraising for immigration defense and translating legal information. In Milwaukee, an advocacy group’s executive director told a local outlet that “children in mixed-status families are experiencing increased anxiety, sleep disruptions and depression” as news of the raids spread.

The psychological toll is broad: even U.S. citizens with Hispanic surnames or accented English report feeling under suspicion. Latinos already targeted in other ways (e.g. by voter ID laws or drug enforcement) say they now feel their very presence is suspect.

Defining Moment

This Supreme Court action is likely to be remembered as a watershed in the debate between national security and individual rights. By sanctioning racial and ethnic profiling in domestic enforcement, the Court majority has significantly shifted America’s civil-liberties landscape.

Future historians may see this as either a necessary tool for immigration control or a dangerous erosion of constitutional guarantees. In dissent, Justice Sotomayor eloquently framed the stakes: “We should not have to live in a country where the Government can seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low wage job”.

Her warning captures the core dilemma. In the end, the nation must decide what it values more – aggressive enforcement or the constitutional principles of equality and due process – and that choice will define this moment in history.