The Sun hurled a fast-moving cloud of charged particles toward Earth in early December, setting off a strong geomagnetic storm that lit skies across North America and tested the resilience of modern technology. The event, tied to an unusually active sunspot and a powerful solar flare, became a vivid demonstration of how activity 150 million kilometers away can ripple through power grids, satellites, aviation, and tourism on Earth.

Solar Flare Ignites a Direct Hit

On December 6, 2025, an M8.1-class solar flare erupted from sunspot region 4299, one of the most energetic events in recent months. The flare launched a full-halo coronal mass ejection (CME), a vast bubble of ionized plasma, on a trajectory aimed squarely at Earth. Traveling at about 535 kilometers per second, the CME was forecast to reach the planet’s magnetosphere on December 9, with an arrival window of plus or minus eight hours.

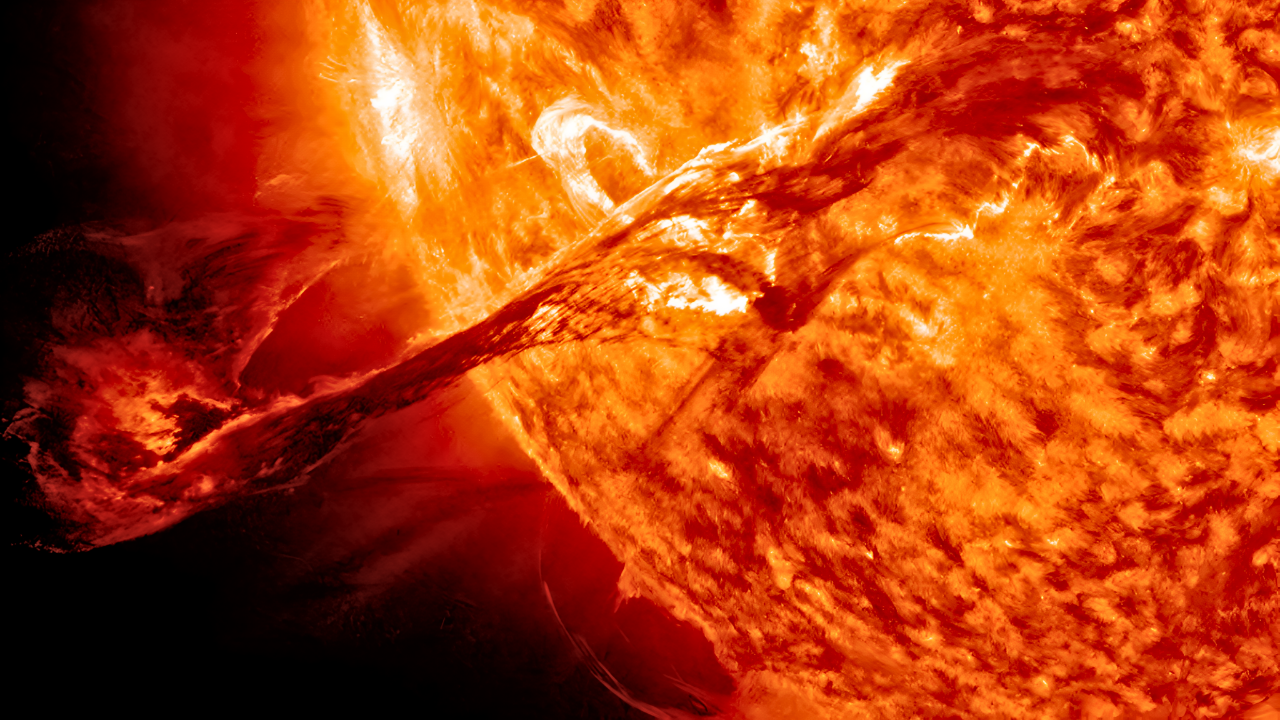

A coronal mass ejection occurs when magnetic fields in the Sun’s corona suddenly restructure and expel enormous quantities of charged particles into space. These ejections can carry billions of tons of plasma and embedded magnetic fields. When they collide with Earth’s magnetic shield, they can trigger geomagnetic storms that disturb the upper atmosphere and induce electric currents at the planet’s surface.

Storm Alerts and Preparedness

As instruments at NOAA and NASA tracked the outward surge of plasma, forecasters initially issued a geomagnetic storm watch, then upgraded it to a storm warning as models converged on a direct impact. By December 8, NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center had posted a G3 (strong) geomagnetic storm alert for December 9, signaling an elevated risk to power systems, spacecraft operations, and certain high-frequency radio communications.

Grid operators in northern latitudes prepared for geomagnetically induced currents that can stress transformers and transmission lines. Satellite operators took protective measures, including altering spacecraft orientations and adjusting operations to limit radiation exposure and potential charging effects. Airlines that routinely fly polar routes evaluated and, in some cases, revised flight paths to reduce radiation exposure to crews and passengers and preserve communication reliability at high latitudes.

Despite the strong classification of the storm, reports of major infrastructure failures did not materialize. Existing mitigation practices, such as real-time monitoring of grid conditions and established satellite protection protocols, appear to have limited physical impacts, even as the event highlighted the uneven level of preparedness among different utilities and regions.

Lights Across the Continent

For many people, the most visible result of the December 9 storm was in the night sky. NOAA’s forecasts indicated that the aurora could be visible across an unusually broad swath of the United States, expanding well beyond the typical high-latitude zones. Projections suggested that 15 to 22 states might see auroral activity, depending on the exact storm strength and local atmospheric conditions.

Observers across parts of Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, the northern Plains, the Midwest, and New England reported sweeping curtains and arcs of green, purple, and pink light. States such as Alaska, Washington, and Maine were expected to have the highest chances of clear, vivid displays, with additional opportunities in places like Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, and portions of the central United States as the auroral oval shifted during the night.

However, cloud cover played a decisive role in who actually saw the spectacle. In some areas, including sections of the Pacific Northwest, thick clouds blocked the view entirely, frustrating residents who had adjusted schedules or traveled in hopes of seeing the lights. The mismatch between the accurately forecast storm and the more uncertain local weather underscored how terrestrial conditions can limit the payoff from even well-predicted space weather events.

Rising Solar Cycle, Growing Economic Stakes

The storm formed part of the broader pattern of Solar Cycle 25, which began in December 2019 and has turned out to be more active than many early forecasts suggested. Sunspot numbers, flares, and CMEs have been running ahead of long-term expectations, prompting NASA, NOAA, and international partners to intensify monitoring and modeling efforts. Regions such as sunspot 4299 have drawn particular interest as indicators of how the cycle may evolve.

The heightened activity carries both risks and opportunities. On the economic side, aurora-focused travel has become a growing niche. The global market for aurora tourism was valued at about $855 million in 2024 and is projected to reach roughly $1.59 billion by 2031, with an estimated compound annual growth rate of 9.4 percent. Northern destinations in Finland, Norway, and Iceland have already reported surges in visitor interest, including hotel search increases of more than 300 percent during peak viewing periods. In North America, Alaska and aurora-prone regions of Canada are investing in upscale lodging and specialized tours to attract visitors drawn by strong solar cycles and reliable forecasting.

At the same time, the same space weather that supports this tourism boom can threaten technologies that underpin the global economy. Geomagnetic storms can disturb GPS precision, disrupt satellite-based communications, and add stress to power networks. While large utilities and space industry firms typically have response plans and technical safeguards, smaller operators and sectors outside historically affected regions may be less prepared as intense solar activity expands its reach.

Communication, Collaboration, and the Path Ahead

The December 9 storm also highlighted persistent communication challenges. NOAA and NASA issued detailed technical bulletins emphasizing that the primary public effect would be enhanced auroral activity and limited infrastructure risk, yet some media coverage emphasized worst-case scenarios and dramatic language. That framing contributed to confusion among audiences unsure whether to expect a picturesque sky display, a major disruption, or both.

For space weather experts, the episode reinforced several themes. Forecasting of CME arrival times and storm intensity has improved significantly, with agencies calling this event’s timing within an eight-hour window despite the vast distance involved. International initiatives such as the International Space Weather Roadmap stress the importance of coordinated data sharing and joint modeling efforts among space agencies as solar activity continues to climb.

Looking ahead, the active phase of Solar Cycle 25 is expected to persist, bringing more flares, CMEs, and geomagnetic disturbances. The December storm served as a test for early-warning systems and infrastructure resilience, as well as a reminder of the need for clear public communication. As reliance on satellites, navigation systems, and interconnected power grids deepens, the stakes of accurate forecasting, robust engineering, and measured messaging will only grow. For scientists, policymakers, and the public, the challenge will be to treat such storms not as causes for alarm, but as catalysts for better preparation and a deeper understanding of Earth’s changing space environment.

Sources

NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC)Strong (G3) Geomagnetic Storm WATCH Valid for 09 Dec 2025 December 6, 2025

Space Weather Live M8.1 solar flare with earth-directed CME December 7, 2025

SpaceWeather.com Archive page for December 8, 2025 December 8, 2025

The Hill / Nexstar Media Wire Solar flare may spark strong geomagnetic storm, northern lights this week December 7, 2025

Space.com Sun unleashes powerful X-class solar flare, knocking out radio signals across Australia December 1–9, 2025

TechStock²Strong G3 Geomagnetic Storm Forecast for December 9, 2025: Northern Lights Chances and Possible Impacts Explained December 7, 2025