Europe (EU27) uses roughly 2,700 TWh of electricity per year. By 2024, nearly half (about 47%) of that came from renewable sources, and wind+solar alone supplied ~27%.

Renewables have surged: by 2023, they made up ~44% of EU generation.

Fossil fuels still account for about 29% of power, with nuclear at 23%. This heavy reliance on external sources – for example, Chinese firms now provide about 90% of the EU’s solar panels – creates strategic vulnerabilities.

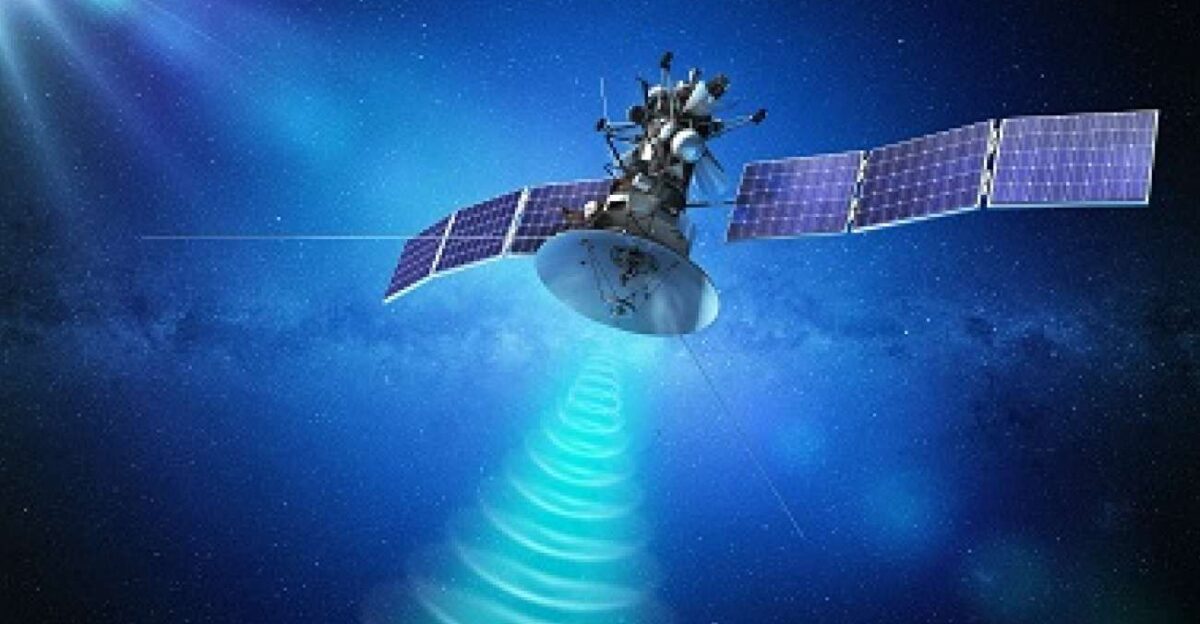

New technologies like space-based solar are being studied to diversify Europe’s energy mix.

Current Limitations

Terrestrial renewables face steep limits. Wind and solar are intermittent: panels drop to zero output at night, and turbines stall in calm weather.

Meeting EU climate targets will require rapidly scaling these to grid scale. Even at current build rates, the EU needs roughly 700 GW of solar by 2030 (about triple today’s capacity).

In 2023, the bloc added only 56 GW of new solar PV.

Such expansion implies huge land use and grid upgrades. Meanwhile, large-scale batteries still cost on the order of $200–400 per kWh, making long-duration storage extremely expensive.

Space Energy History

The idea dates back to 1968, when NASA engineer Peter Glaser first proposed solar power satellites.

He even patented a microwave transmission system in 1973. Early designs envisaged multi-thousand-ton spacecraft, and U.S./ESA studies in the 1970s quickly found launch costs made SBSP uneconomical.

Research continued at low levels: Japan’s space agency and China experimented with ground beaming tests, but for decades, the vision remained largely science fiction.

In 2023, Caltech’s SSPD-1 satellite proved the first orbital microwave power transmission. Still, no country has yet built a commercial solar power station in space.

Technology Convergence

Modern advances are closing past gaps. New lightweight solar cells (flexible panels) now reach ~150 W per kg. At the same time, reusable rockets like SpaceX’s Starship could slash launch costs by an order of magnitude.

Notably, small-space experiments have succeeded at wireless power transfer: Caltech recently demonstrated an orbital satellite beaming detectable microwaves back to Earth.

NASA’s latest “Innovative Heliostat Swarm” concept replaces heavy solar arrays with swarms of steering mirrors, reducing structure mass by ~40%.

Each of these breakthroughs compounds to make orbit-based solar steadily more plausible.

Breakthrough Study

On August 20, 2025, a team at King’s College London published a game-changing continental-scale model. Their study showed space-based solar could replace roughly 80% of Europe’s land-based wind and solar generation by 2050.

Using all 33 countries’ grids, they found this shift could lower total system costs by 7–15% (about €36 billion per year).

Lead researcher Dr. Wei He noted that in space panels can always face the sun, making output “nearly continuous” compared to Earth-bound systems.

This work suggests SBSP might dramatically complement European renewables. For Europe, that could mean far cheaper and cleaner power.

Economic Impact

The King’s study even quantifies the upside. Replacing most land-based wind/solar with SBSP could cut the EU’s total energy system costs by 7–15% (about €36 billion/year), mainly by saving land and balancing supply.

These savings would be especially valuable in northern Europe, where low sunlight makes terrestrial solar less productive.

In practical terms, each 10% of cost reduction corresponds to roughly €3 billion saved annually. The team stresses that these benefits hinge on SBSP costs falling into the assumed range.

Still, it’s one of the strongest cases yet that if the technology works, it could reshape European power economics.

Lead Researcher Perspective

Professor Wei He, the study’s lead author, was cautiously optimistic. He told the press that “for the first time we have shown the positive impact this technology could provide for Europe… its vast economic and environmental potential” if deployed.

He also noted that reaching net-zero by 2050 “is going to require a significant shift… and [this] emerging technology could play a pivotal role” in that transition.

He says SBSP may be a game-changing complement to land renewables – the model validates the concept, but building it in practice will be the next challenge.

Storage Revolution

One of space solar’s biggest promises is cutting Europe’s battery needs. If panels beam power 24/7, Europe could greatly reduce its reliance on costly storage.

The King’s model found that SBSP would slash battery demand by over two-thirds.

This matters because today’s grid batteries cost roughly $200–400 per kWh, making long-duration storage extremely expensive.

For example, storing 1 TWh (1,000 GWh) of energy would cost on the order of $200–400 billion, costs that SBSP could largely avoid. Thus, Europe might not need to build extra gigawatt-scale battery parks just to cover peak demand.

Global Competition

Countries worldwide are racing to prove SBSP. Japan’s JAXA plans to launch OHISAMA in 2025 – a 180-kg microsatellite to beam about 1 kW from 400 km altitude.

China’s Xidian University has already erected a 75-meter ground tower for end-to-end beaming tests.

In the U.S., Caltech’s SSPD-1 satellite recently proved in-orbit power beaming, transmitting microwaves from space to Earth.

Even Europe has joined: ESA and industry are funding lab and high-altitude experiments to integrate these subsystems. Each demonstration validates a key piece (efficient cells, reliable transmitters, safe receivers), and together these projects rapidly lower the risk of SBSP technology.

Reality Check

NASA’s 2024 analysis remains sobering. It finds space-based solar designs cost 12–80 times more per kilowatt-hour than equivalent Earth renewables.

Building even a few gigawatts would require tens of thousands of tons in orbit – implying hundreds of billions in launch costs under today’s prices.

In fact, NASA’s Erica Rodgers bluntly asked, “Do you want to put all that money into [space solar] if you could reap the benefits from using terrestrial energy right now?”.

The agency warns that without dramatically cheaper launches and satellites, SBSP could be an expensive detour for decades.

Industry Skepticism

Unsurprisingly, many traditional energy and finance players are hesitant about SBSP. Utilities see predictable returns in ground-based renewables, not in giant orbital farms. Even insurance markets are unprepared to cover decades-long space infrastructure.

After NASA’s report, skeptics pointed out that space designs were “12 to 80 times more expensive” than terrestrial options.

In practice, even governments have limited SBSP funding for research projects. Commentators quip that today, SBSP remains “an idea looking for billions” – and the dollars have not yet materialized.

With such doubts, most energy boardrooms are watching rather than working on space solar initiatives.

European Response

Europe isn’t standing still. At the 2022 ESA ministerial, member states approved the SOLARIS initiative and set aside roughly €3 million for SBSP feasibility studies.

Now, ESA is preparing a decision on a full development program by late 2025.

Meanwhile, contracts have been given to industry (e.g. Thales Alenia Space) to study in-space assembly and other critical SBSP technologies.

National agencies in countries like Germany, France and the UK have begun small SBSP R&D projects. Europe is quietly laying the groundwork – but large-scale deployment still hinges on the 2025 decision.

Manufacturing Challenges

Building SBSP hardware poses unprecedented manufacturing challenges. Orbital power stations will need arrays spanning several kilometers.

Conventional satellite factories (which make TVs- and homes-sized devices) can’t scale to this. Instead, engineers envision automated production lines that churn out gigawatts of solar film and beam electronics.

One report notes SBSP will rely on “robotized assembly in space”. This could mean fleets of robotic arms and laser welders building and welding modules in orbit for months or years. For example, factories might be as automated as semiconductor plants but assemble structures the size of stadiums.

Even small component failures would be hard to fix at 36,000 km altitude.

Expert Outlook

Experts agree SBSP won’t happen overnight. Most say launch costs must fall below a few hundred dollars per kg to compete.

SpaceX’s Starship ultimately claims around $20–30 per kg, but that remains to be proven. In any case, analysts project only pilot projects before the mid-2030s.

One report expects SBSP “pilot installations” by the late 2030s and utility-scale plants in the 2040s.

A full-scale space power farm is likely a decade or more away, barring unexpected breakthroughs. In contrast, terrestrial renewables will continue to dominate energy expansion through the 2020s. Absent miracles, the first real SBSP networks won’t arrive this decade.

Future Questions

Can Europe afford to ignore SBSP while competitors test it? The King’s study gave new scientific backing to the idea, but it also underscored the massive costs.

Even its authors admit space solar’s costs are “1 to 2 orders of magnitude” above what’s needed to be viable.

Now Europe faces a choice: keep pouring billions into proven wind, solar and storage, or invest in the risky frontier of orbital solar.

That question – whether SBSP is the next big frontier or an expensive distraction – will shape policy and investment decisions as 2030 approaches.

Policy Implications

The EU’s renewable targets are rising: law now demands 42.5% renewable energy by 2030 (vs ~24.5% today). Space solar could, in theory, help meet that goal while also reducing EU dependence on Chinese-made panels (China supplies ~90% of EU solar imports).

But deploying SBSP would require enormous coordinated investment – effectively an EU-wide megaproject – and even new international agreements to manage orbital power stations.

For context, €3 million is just a down payment: full SBSP deployment could take tens of billions or more.

Policymakers must weigh whether those risks and costs are worth accelerating decarbonization, or whether the money is better spent on ground-based tech.

Geopolitical Dimensions

Space-solar also adds a geopolitical layer. Some analysts warn that if Europe lags, it could face a new dependency on countries that master the technology.

China, for example, is aggressively pursuing SBSP and already dominates global solar manufacturing.

Military planners note that orbital power stations could be potential targets in conflict, and conversely could be used to power forward bases or directed-energy weapons.

Currently, no international treaty covers beaming satellites or cross-border microwave links, so SBSP could create legal and security gray zones. In short, space power may soon require its own diplomacy and safeguards.

Environmental Trade-offs

SBSP eliminates land-use conflicts on Earth, but it isn’t carbon-free. Launching thousands of rockets to build orbital power stations would emit enormous CO₂.

For example, Orbital Today notes that even one large launch “raises the question of the ‘greenness’ of the technology…if we are talking about the level of greenhouse gas emissions”.

In total, early construction could emit carbon comparable to decades of coal-fired power. And then there’s space debris: dozens of multi-ton satellites over GEO would add collision risk.

Ultimately, SBSP’s payoff depends on each station lasting 15–20 years in space without failure.

Social Acceptance

Public perception may be an unexpected hurdle. Early SBSP proposals met with unease over invisible microwave beams.

As one review found, “a general public perception that microwaves are hazardous has been a key obstacle” to accepting space power.

Nearby communities might resist building a giant antenna, fearing health risks. Engineers insist beam intensity could be kept very low (comparable to cellphone signals), but they know outreach is crucial.

Advocates may spend almost as much time on public communication and health studies as on rockets and panels.

Defining Moment

Space-based solar power could be a defining pivot for Europe’s energy future. As Prof. Wei He puts it, we’re now ready to move “this blue-sky idea into testing at a large scale”.

Europe faces a choice: invest in the risky next frontier of SBSP or stick with tried-and-true renewables.

If SBSP succeeds, it could provide massive, continuous clean power with minimal land use, helping Europe lead on climate and energy security.

But if costs and tech hurdles remain too great, it risks becoming an expensive experiment. The next decade’s choices will determine which path Europe takes.