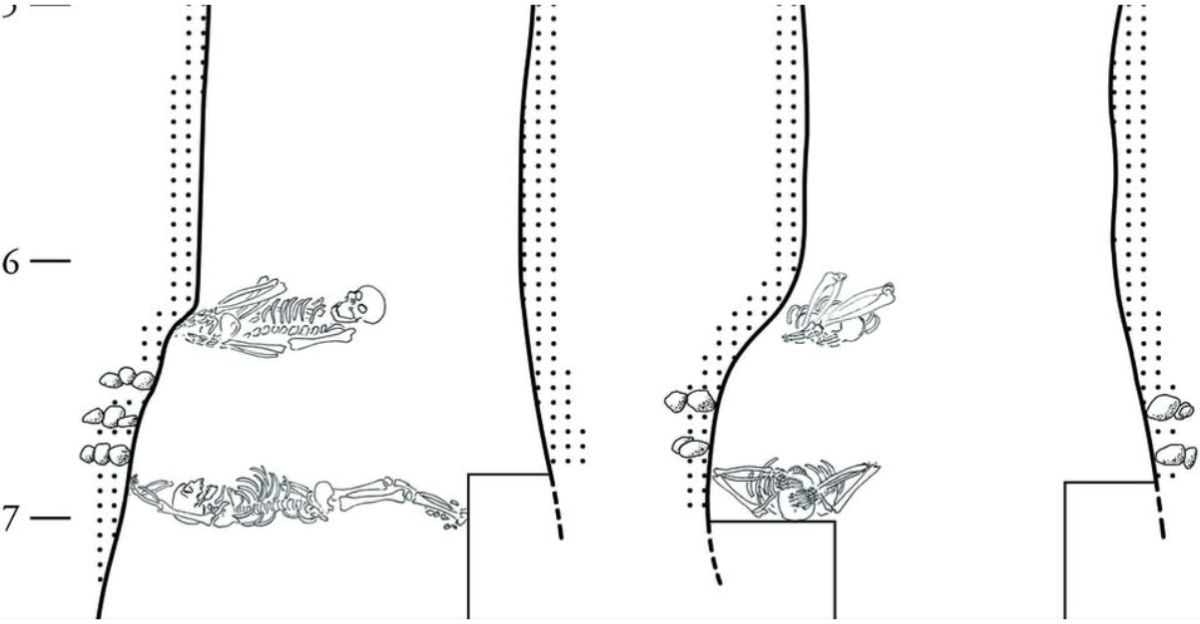

Deep within South Moravia’s Krumlov Forest, archaeologists uncovered a burial that would puzzle researchers for years. Concealed in the shadows of an ancient chert mine lay the remains of two women, a newborn, and part of a dog’s skeleton.

The Moravian Museum in Brno reports that the arrangement was striking … one woman positioned above the other, the infant placed gently on the elder’s chest. The scene suggested either a ritual act or a tragedy frozen in time.

With no written records from this Neolithic community, its story survives only through the silent testimony of bone, soil, and stone tools, entombed in darkness for more than six thousand years.

South Moravia’s Ancient Stone Boom

Long before the region was farmland, South Moravia thrived as one of Europe’s earliest industrial zones. Around 4,000 B.C., chert – an exceptionally hard stone – was mined here to make axes, blades, and scrapers.

According to archaeologist Martin Oliva, who has studied the site extensively, Krumlov’s mines were among the most important in Central Europe. Work was grueling, carried out by hand with antler picks and stone hammers in cramped tunnels. The mine’s scale suggests an organized labor force, with men, women, and possibly children contributing to the dangerous extraction work.

Life in the Depths of Neolithic Mines

The Krumlov chert mines were not open pits; they were narrow vertical shafts plunging deep underground. Workers likely carried animal-fat lamps or torches, breathing air thick with dust. Anthropological studies suggest that Neolithic miners endured extreme conditions like low light, poor ventilation, and constant physical strain.

The tools found on-site – flint blades and hammerstones – bear the polish of heavy, repeated use. These mines were not seasonal side projects but the lifeblood of the community, fueling trade networks that reached far beyond South Moravia’s forested hills.

Burial Beneath the Industry

The burial site was discovered about 30 feet below ground in a disused mine shaft. The older woman lay at the bottom, the younger directly above her, with the infant positioned carefully on the elder’s chest. The partial dog skeleton was placed nearby.

Archaeologists from the Moravian Museum say such a deliberate arrangement suggests symbolic intent, perhaps linked to beliefs about the afterlife or the protection of the mine. Yet, the meaning remains elusive without artifacts that clearly define the ritual.

A Culture on the Edge of Change

The burial dates to roughly 4,050–4,340 B.C., when Central Europe shifted from nomadic hunting to permanent farming. In South Moravia, settlements clustered near fertile river valleys, but the mines drew workers into the forest.

According to Oliva, these communities blended farming with specialized crafts, creating complex social structures. The burial beneath the mine could symbolize the community’s dependence on chert or reflect the toll such work exacted on its people.

Two Sisters, One Unrelated Child

Radiocarbon dating placed both women firmly in the Neolithic era, and DNA analysis later revealed they were biological sisters. The older woman was likely in her late 30s, a considerable age for the time, while the younger may have been in her mid-to-late 20s.

Surprisingly, the baby was unrelated to either. This fact, confirmed by genetic testing at the University of Copenhagen, deepened the mystery: why include an unrelated infant in such an intimate burial?

Skeletons Scarred by a Lifetime of Work

Analysis of the women’s skeletons revealed lives shaped by relentless work. Both showed spinal compression and joint wear typical of miners who carried heavy loads in confined spaces. The older sister bore a partially healed forearm fracture, suggesting she returned to work before fully recovering.

According to osteoarchaeologist Marie Nováková, the injuries align with mining-related accidents. For these women, labor was not optional … it was survival.

Tough Childhood in the Stone Age

Microscopic inspection of the sisters’ teeth revealed enamel defects and signs of malnutrition or illness during childhood. This likely reflected food scarcity in early years, a challenge common in Neolithic Europe.

Yet an isotope analysis of their adult bones indicated a protein-rich diet heavier in meat than typical farming communities. Researchers suggest the mine’s labor demands have earned miners access to better rations, possibly from hunting in surrounding forests.

The Canine Connection

The presence of the dog’s bones puzzled researchers. In some Neolithic cultures, dogs were buried with humans as companions or spiritual protectors. Zooarchaeologist Petr Květ noted that the dog’s remains were incomplete, with no apparent signs of sacrifice.

Whether the animal died naturally, was symbolically included, or had a direct role in mining life, such as guarding the site, remains uncertain.

Breathing Life Into the Long Dead

For over a decade, the sisters existed only as skeletal remains and lines in DNA reports. In 2024, researchers at the Moravian Museum launched an ambitious effort to give them faces again, drawing on forensic techniques and genetic evidence.

Project lead Tomáš Vávra said the goal went beyond science; it was also about forging a human connection, allowing modern viewers to meet individuals whose lives had long remained silent shadows in the prehistoric record.

Reconstructing the Past, Layer by Layer

The reconstruction began with high‑resolution CT scans of the sisters’ skulls, capturing details accurate to mere fractions of a millimeter. From these scans, researchers built precise 3D models, creating a digital foundation for the faces that had been lost for over six millennia. Forensic artists then layered virtual muscle, skin, and tissue, guided by anatomical standards and clues from genetic data.

Once the virtual portraits were complete, they were transformed into physical models cast in silicone and plaster. Prosthetic eyes brought depth to their gaze, while human hair implants and clothing, woven from plant fibers like flax and nettle, returned a striking sense of realism.

The result was more than a technical feat; it was the reappearance of people who had not been seen since the Stone Age.

Ancient DNA Reveals Striking Features

DNA analysis revealed striking personal details. The younger sister most likely had dark hair paired with hazel or green eyes, while the elder sister probably had blonde hair and blue eyes. Scientists estimated skin pigmentation using probabilities drawn from genetic markers, adding further nuance to their reconstructed appearances.

As project lead Tomáš Vávra reflected, these insights “helped us see them not as anonymous ancestors, but as women you might pass on the street—if only you could step back 6,000 years.” This glimpse into their individuality bridges the vast gulf of time, transforming distant figures into relatable human beings.

Dressing the Women of 4,000 B.C

Clothing reconstructions were meticulously crafted based on textile fragments uncovered at Neolithic sites across Europe. The older sister’s hair was gathered into a delicate net woven from plant fibers, while the younger sister’s hair was styled with braided fabric strands.

Their simple blouses and wraps, dyed with muted earth tones derived from natural pigments, completed the ensemble. Every detail was chosen to reflect everyday wear rather than ceremonial dress, anchoring the reconstructions firmly in the realities of daily life six millennia ago.

Their Public Debut

The completed models are now on display at the Moravian Museum in Brno, inviting visitors to meet the sisters face-to-face. They are no longer shrouded in the mine’s darkness but illuminated by gallery lights.

Museum curator Petra Urbanová noted the profound public response: “People linger, studying every line and contour. It’s a powerful reminder that history is made of people, not just artifacts.” This encounter transforms distant prehistory into an intimate human story.

The Unsolved Questions That Remain

Despite the reconstructions, the burial raises unanswered questions. Was it a familial tragedy, a work accident, or part of a ritual tied to mining? Why was an unrelated newborn included, and what was the dog’s role?

Researchers caution against definitive conclusions. As Oliva noted, “Archaeology gives us evidence, but not always the full story.”

Rethinking Social Roles in Prehistory

The sisters’ injuries reveal that neither was spared from the grueling demands of hard labor, despite their close biological ties. This challenges traditional assumptions that physically intense mining work was reserved for men or only lower-status individuals.

Instead, it suggests that Neolithic social inequality was shaped more by necessity than gender, with all community members—regardless of status—compelled to contribute to survival in a harsh environment.

The Cutting‑Edge Science of Face‑Building

Facial reconstruction is a multidisciplinary endeavor that combines CT imaging, 3D printing, forensic anatomy, and genetic sequencing. Each stage involves careful cross-referencing with population data from Neolithic Central Europe to ensure accuracy.

Without DNA evidence, key traits like skin, hair, and eye color would have remained educated guesses. The sisters’ reconstructions highlight how advanced technology has become, transforming ancient skeletal remains into vivid, relatable faces once again.

Joining the Global Gallery of Ancient Faces

These reconstructions join a growing list of hyperrealistic Stone Age faces displayed worldwide, from hunter-gatherers in Belgium to warriors in Siberia.

Each project bridges the emotional distance between modern viewers and prehistory, reminding us that these were real individuals with families, work, and daily challenges – not distant, abstract ancients confined to textbooks.

Gazing Into 6,000‑Year‑Old Eyes

Each facial reconstruction offers a rare window into the lived experiences of people from millennia past. These projects transform distant history into relatable human stories by revealing nuanced expressions and individual features.

They remind us that behind every archaeological find lies a person who laughed, struggled, and dreamed, bringing the distant past vividly into the present and deepening our understanding of humanity’s enduring spirit.

From Mine Shaft Darkness to Museum Light

More than six millennia after their burial, the sisters have emerged from the darkness of the ancient mine into the spotlight of modern science. Their reconstructed faces are powerful symbols of endurance and connection across time, revealing the extraordinary stories etched in bones and DNA.

Though many details of their lives remain a mystery, the collaboration of archaeologists, forensic specialists, and geneticists has ensured their presence endures, reminding us that even after thousands of years, a human face can still captivate and move us profoundly.