Geologist Dr. Jason W. Ricketts was mapping rocks near Van Horn, Texas, when he spotted unusual bone fragments weathering from soft shale at the Indio Mountains Research Station.

The darker pieces didn’t match the surrounding rock. Ricketts realized he’d found something extraordinary—a discovery that would change our understanding of an ancient plant-eater’s range.

West Texas rarely yields fossils, making any bone find remarkable. However, this discovery proved far more significant than a single scattered fragment.

Rising Stakes in Paleontology

Early Cretaceous fossil discoveries across North America are rare and fragmented. Scientists have noticed a strong bias toward younger fossils—newer rock layers yield complete skeletons, while older rocks from 115 million years ago preserve only scattered bones.

This gap means every early Cretaceous find matters, no matter how incomplete. West Texas had barely been explored for dinosaur fossils, leaving scientists with big knowledge gaps. The region’s rocks promised untold secrets about ancient animals and their movements across North America.

The Tenontosaurus Legacy

Tenontosaurus was a medium-sized plant-eating dinosaur known mainly from Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, and north-central Texas. Two species made up this genus: Tenontosaurus tilletti and Tenontosaurus dossi.

These two-legged herbivores had distinctive long tails stiffened by bony tendons along their spines. Scientists linked them to duck-billed dinosaurs.

Earlier research on Montana and Wyoming fossils had established what we knew about Tenontosaurus anatomy and behavior. West Texas had never appeared on any Tenontosaurus range map.

The Geographic Mystery

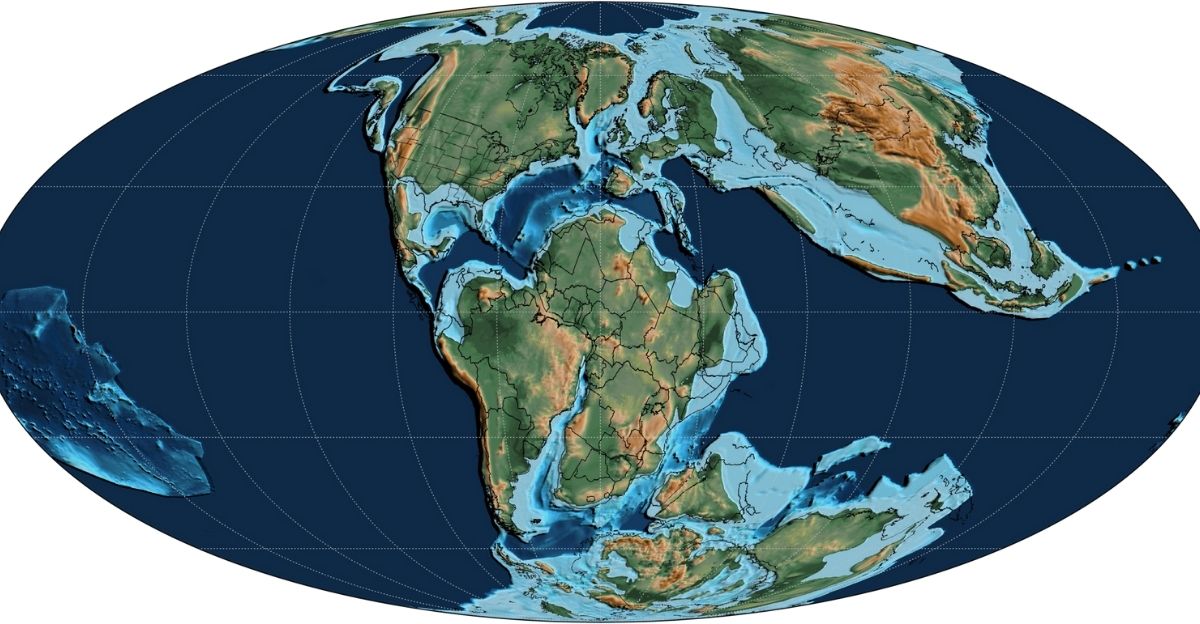

Paleontologists saw a major gap in the Tenontosaurus fossil record. Previous fossils came from spots roughly 250 miles east of Arizona sites and about 560 miles northeast of the southernmost known Texas location. This gap puzzled researchers trying to understand how the species spread across Early Cretaceous North America.

Did Tenontosaurus live farther south, or did fossil preservation simply hide evidence? The Yucca Formation in far Western Texas, a Lower Cretaceous unit that preserves ancient river systems, had received almost no paleontological attention. Few scientists expected major finds there.

Historic Discovery

While mapping rocks in 2025, Ricketts discovered three tail vertebrae and a femur piece—plus smaller fragments—from a Tenontosaurus that lived approximately 115 million years ago in West Texas’s Yucca Formation. These bones made Tenontosaurus history: the southernmost confirmed record ever found.

This single discovery extended the genus’s known range hundreds of miles southwest, from Montana and Wyoming down to the Indian Mountains. The specimens matched known Tenontosaurus skeletons perfectly. Carbon dating of the Yucca Formation placed them at the Aptian-Albian boundary of the Early Cretaceous.

The Species Reimagined

The Ricketts discovery challenged everything scientists thought about Tenontosaurus. Previous research has shown that the species lives mainly in cooler northern climates, such as Montana and Wyoming. West Texas sat hundreds of miles farther south, in what paleontologists now recognize as a hotter, drier region during the Early Cretaceous.

This southern specimen proved Tenontosaurus could handle far more diverse climates and environments than anyone realized. Dr. Ricketts emphasized the finding proved Tenontosaurus “lived as far south as West Texas,” completely rewriting textbook range maps and basic assumptions about Early Cretaceous animals.

A Serendipitous Family Effort

Dr. Ricketts was doing unrelated geological mapping when he made his discovery. “I wasn’t looking for fossils that day,” he recalled. “I was studying the rocks when I noticed fragments weathering from soft shale. I simply picked them up—no digging needed.”

The find proved so significant that Ricketts brought his family back to help. “My wife and children came out to help collect the pieces,” he said. His family’s help turned a routine field trip into a memorable paleontological event. The fossils now sit in UTEP’s Biodiversity Collections for future study.

Ecosystems of the Yucca Formation

The Yucca Formation preserves an ancient river landscape from 115 million years ago. Paleontological evidence indicates that Tenontosaurus shared its West Texas ecosystem with dangerous predators. Deinonychus, a clever pack-hunting theropod, and Acrocanthosaurus, a massive meat-eater, lived in the same rock layers. Smaller plant-eating dinosaurs also inhabited the region.

Early flowering plants were just beginning to spread during this time, offering new food sources. Ancient rivers and lakes provided plenty of plants for herbivore herds. Finding Tenontosaurus here suggested complex Early Cretaceous food webs stretched much farther south than scientists had previously documented.

Range Expansion and Dispersal Patterns

The West Texas discovery offers crucial insights into how dinosaur species dispersed across North America during the Early Cretaceous. Mapped across the Western Interior, Tenontosaurus now shows a geographic range spanning roughly 1,000 miles from north to south.

The species colonized different environments across multiple states and rock formations. Dr. Ricketts used the fossil’s location within dated Yucca Formation rocks as a “time stamp” connecting Tenontosaurus directly to the Aptian-Albian age boundary.

Comparative analysis now lets paleontologists study whether southern and northern populations faced different climates and predators. This pattern suggests Tenontosaurus was successful and highly adaptable.

Fragmentary Fossils, Monumental Significance

A fascinating paradox emerges: the most important discoveries often involve incomplete material. The West Texas Tenontosaurus consists only of three tail vertebrae, part of a femur, and smaller pieces.

Yet these scattered bones carry major importance because early Cretaceous rocks yield so few complete fossils. Scientists have documented a strong bias toward younger fossils in sampling, as later time intervals tend to dominate, while earlier periods remain poorly understood.

This means fragmentary early Cretaceous specimens sometimes teach us more than complete late Cretaceous skeletons. The Ricketts discovery demonstrates how careful mapping, combined with anatomical analysis, extracts maximum value from minimal material. West Texas became a paleontological frontier.

West Texas Emerges as Paleontological Frontier

The discovery sparked fresh scientific interest in West Texas as a major paleontological region. Dr. Ricketts stressed that the finding should inspire further exploration in this “largely underexplored” area for dinosaur fossils.

The Indio Mountains Research Station, a UTEP-owned laboratory spanning more than 41,000 acres in southeastern Hudspeth County, became a priority fieldwork target. Researchers recognized that similar rock exposures across the region likely contain additional fossils waiting to be discovered.

Each new fossil site strengthens arguments for protecting university research lands in the desert Southwest. According to Liz Walsh, interim dean of UTEP’s College of Science, “major discoveries happen when we least expect them.” West Texas paleontology entered a new era.

Publication and Scientific Validation

Scientists formally documented the discovery in a peer-reviewed paper published in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin in 2025. The research team included Dr. Jason W. Ricketts from UTEP’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Resource Sciences, Dr. Spencer G. Lucas from the New Mexico Museum, and Sebastian G. Dalman from Montana State University.

The paper, titled “An Ornithopod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of West Texas,” explained why the West Texas bones closely matched known Tenontosaurus skeletons. The authors carefully called the specimen “cf. Tenontosaurus sp.”—showing resemblance while noting missing diagnostic features. This careful approach built credibility within the paleontological community.

Implications for Understanding Early Cretaceous Life

The West Texas Tenontosaurus raises important questions about how dinosaurs survived different environments during the Early Cretaceous. Why did this species thrive in West Texas when other plant-eaters left no fossil record there? Did Tenontosaurus herds migrate seasonally to find resources in different climates? Did southern populations evolve differently from northern relatives?

Scientists cannot yet answer these questions, but the discovery provides a foundation for tackling them. Future fieldwork at the Indio Mountains site may uncover additional teeth, leg bones, or footprints, revealing how Tenontosaurus moved across ancient river edges. New specimens could reveal population size, growth patterns, and feeding habits.

Protecting Research Lands and Future Discovery

The Indio Mountains Research Station serves as a vital resource for paleontological research in the American Southwest. Dr. Ricketts’ accidental discovery while mapping rocks exemplifies how dedicated fieldwork on preserved research lands can lead to major breakthroughs. The station’s location and rock formations contain vast areas of sedimentary rock likely filled with fossils.

Erosion destroys fragile specimens every season; protecting research access grows increasingly important. University-owned natural laboratories allow scientists to conduct long-term research driven by curiosity rather than commercial pressure. The Ricketts discovery strengthens arguments for protecting and maintaining access to such lands. As Dr. Ricketts reflected: “It’s a privilege to contribute even a small piece to that bigger story.”

Rewriting Dinosaur History One Bone at a Time

The West Texas Tenontosaurus discovery teaches a fundamental truth: even in well-studied regions, major surprises await careful observers. One afternoon of geological mapping yielded bones that rewrote continental-scale range maps.

Three-tailed vertebrae and a femur fragment fundamentally challenged assumptions about the boundaries of early Cretaceous animals and the extent of their ecosystems. This finding demonstrates that North America’s dinosaur record remains incompletely understood, despite centuries of scientific work. Countless additional specimens likely remain hidden in desert exposures across the continent.

As Dr. Ricketts noted, “there’s still much to learn about our region’s prehistoric past.” What other species roamed West Texas during the Early Cretaceous? How did these animals interact in the Yucca Formation? The discovery raises tantalizing questions that future paleontologists will pursue across the Southwest, ultimately rewriting the history of dinosaurs in America.

Sources:

Phys.org, Dinosaur discovery extends known range of ancient species, November 2025

Earth.com, Rare fossil rewrites the story of early dinosaurs in the Southwest, January 5, 2026

SciNews, New Fossils from West Texas Extend Known Range of Tenontosaurus, November 10, 2025