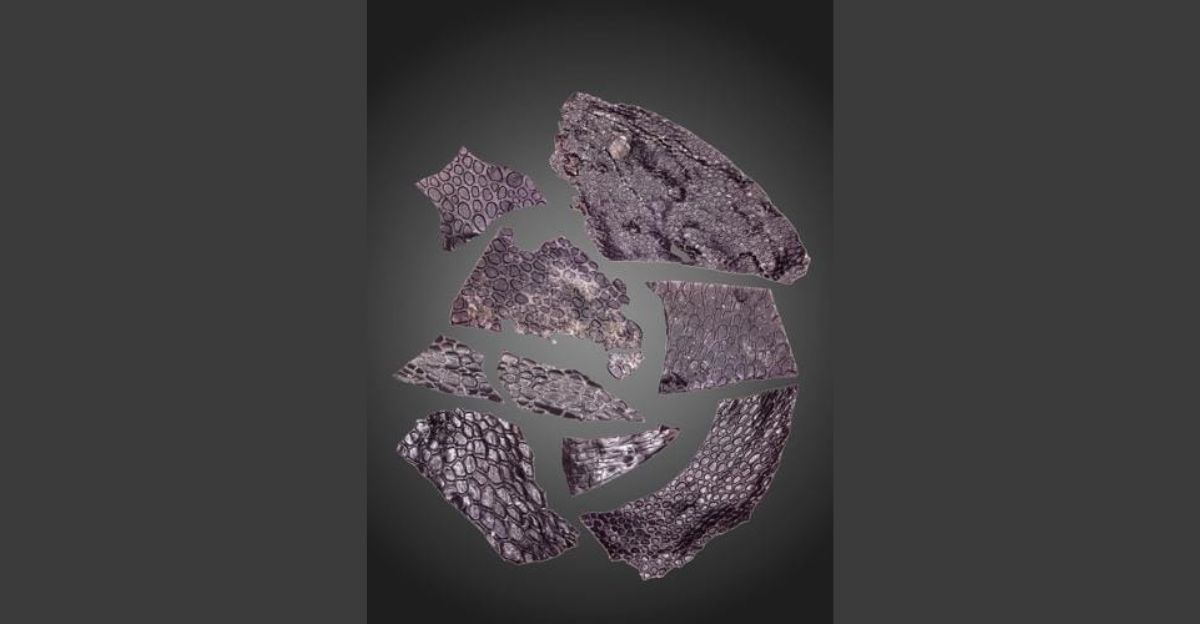

It shouldn’t exist. In the world of paleontology, soft tissue is supposed to rot away in weeks, leaving only bone and teeth behind. Yet, in a limestone cave in Oklahoma, scientists found something that defied the laws of decay: a piece of reptile skin, perfectly preserved for 290 million years.

It is the oldest skin fossil ever discovered, shattering the previous record by over 130 million years and providing a rare, tactile glimpse into a world that vanished long before the first dinosaur took its first breath.

A Natural Vault Hidden In Plain Sight

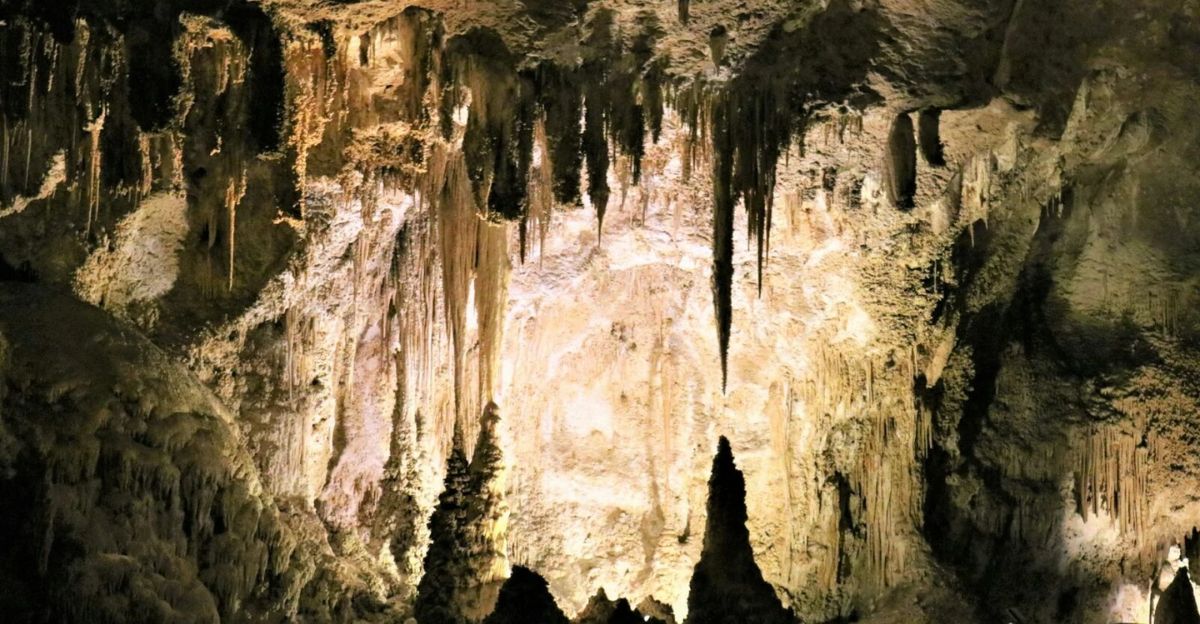

The discovery didn’t happen in a high-tech lab, but in the dark, clay-filled crevices of the Richards Spur cave system near Lawton, Oklahoma. This site was once an active limestone cavern during the Permian period, a natural trap where ancient animals fell to their deaths or were washed in by prehistoric storms.

For nearly 300 million years, the cave served as a sealed vault, protecting its contents from the oxygen and bacteria that typically erase all traces of soft, organic life.

Smaller Than A Fingernail, Older Than Pangea

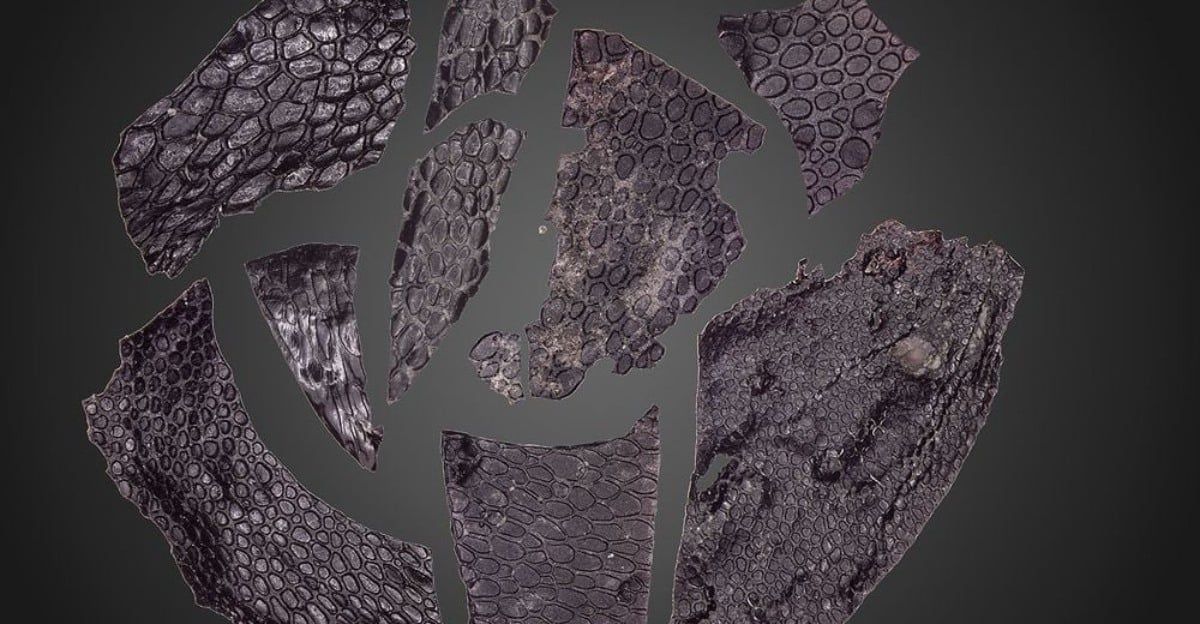

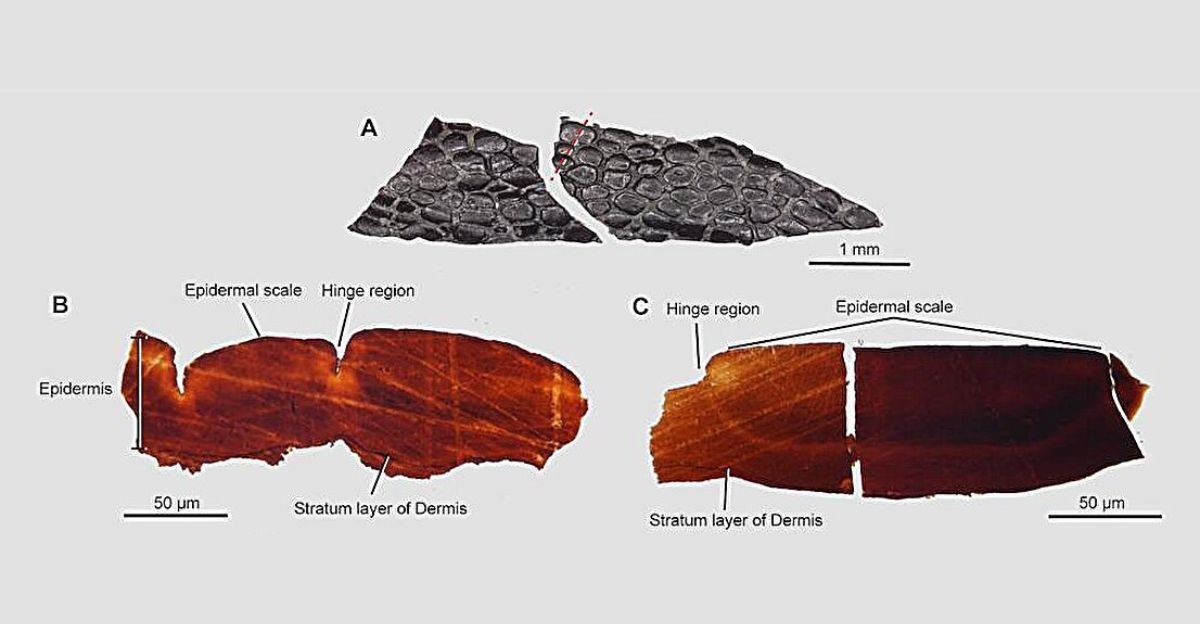

The artifact itself is deceptively small—a fragment smaller than a human fingernail—but its implications are massive. While most fossils are stone replacements of bone, this specimen retains the actual three-dimensional structure of the skin, frozen in time.

It dates back to the Paleozoic Era, a time when Earth’s landmasses were crushing together to form the supercontinent Pangea. To hold this tiny flake is to hold a biological relic that is 60 million years older than the earliest known dinosaurs.

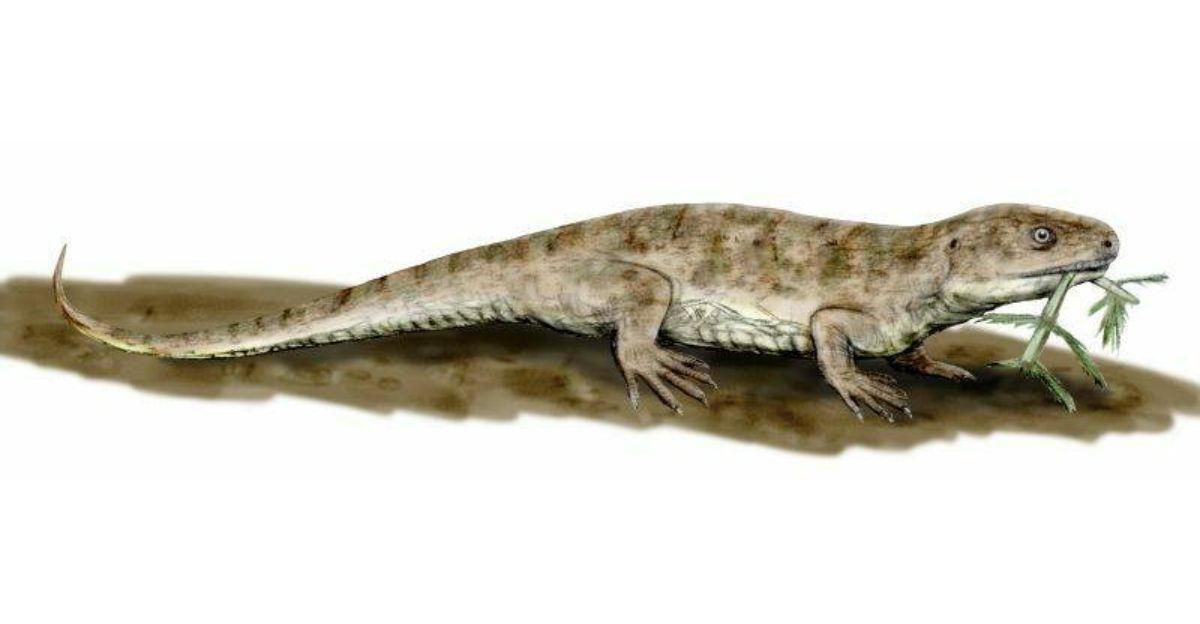

The Creature Behind The Skin

Paleontologists believe this ancient armor belonged to Captorhinus aguti, a small, lizard-like reptile that scurried across the Permian landscape. It wasn’t a monster, but a survivor—an early member of the amniotes, the critical lineage that eventually gave rise to modern reptiles, birds, and mammals.

While skeletons of this creature are common, finding its soft exterior is a “black swan” event, transforming a standard skeletal reconstruction into a fleshy, living animal in the minds of scientists.

The “Spacesuit” For Conquering Land

This skin represents more than just texture; it marks a pivotal moment in the history of evolution. As Ethan Mooney, the study’s author, explains, the epidermis was the ultimate adaptation—a biological “spacesuit” that allowed animals to leave the water and survive on dry land finally. Before this, life was tethered to moisture.

This fossil proves that by 290 million years ago, nature had already engineered the complex, water-tight barrier needed to conquer the continents.

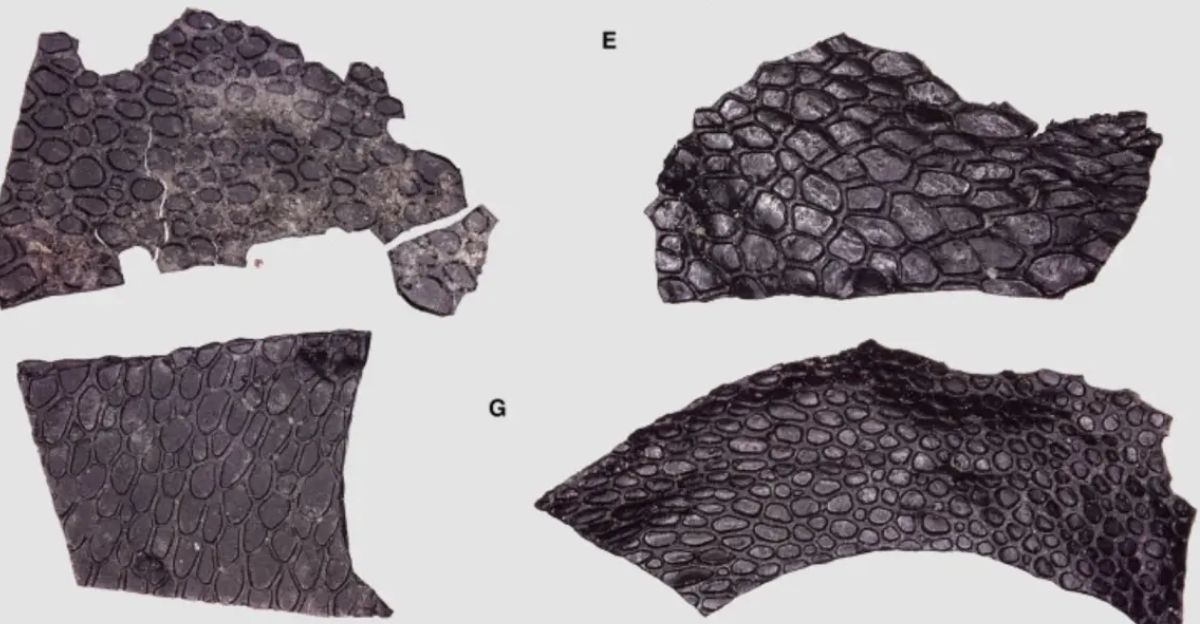

A Texture Eerily Similar To Today

What makes the find truly haunting is how familiar it looks. The fossilized skin features a pebbled surface indistinguishable from the skin of a modern crocodile living today. This suggests that the blueprint for reptile skin was perfected almost immediately and has remained virtually unchanged for hundreds of millions of years.

Evolution found a winning design in the Permian era and stuck with it, bridging a gap of deep time that is almost impossible to comprehend.

The Secret Ingredient

How did fragile skin survive for eons? The answer lies in a strange geological twist: the cave was permeated with petroleum. Oil and tar from the Woodford Shale seeped into the cave, saturating the clay and essentially pickling the animal remains in a hydrocarbon bath.

In a supreme irony, the raw material of fossil fuels—usually the result of destroyed life—acted as the ultimate preservative, waterproofing the skin and locking it away from decay.

A Cave System Of Traps And Treasures

Richards Spur is unique in the fossil record, described by experts as an “upland” site that captured life from hills and plateaus rather than just swamps. The cave system was a honeycomb of vertical shafts that unsuspecting animals plunged into, becoming entombed in fine sediment.

This unique depositional environment creates what scientists call a “Lagerstätte”—a sedimentary deposit that exhibits extraordinary fossils with exceptional preservation—making it one of the most important windows into the Permian world.

The Hobbyists Who Found History

This scientific breakthrough wasn’t made by a university expedition, but by Bill and Julie May, a pair of dedicated fossil enthusiasts who have spent years scouring the quarry. They noticed the unusual texture on the small limestone blocks and donated the specimens to the University of Toronto for study.

Their sharp eyes and generosity bridge the gap between amateur collecting and high-level academic research, proving that significant discoveries can still come from passionate individuals on the ground.

Why Soft Tissue Is The Holy Grail

To understand the magnitude of this find, one must understand the rarity of soft tissue fossilization. Typically, when an animal dies, its soft parts are the first to decompose, consumed by scavengers or broken down by bacteria within days.

For skin to mineralize before it rots requires a “Goldilocks” set of conditions: rapid burial, low oxygen, and the introduction of stabilizing minerals. The Richards Spur fossil managed to tick every impossible box, surviving against odds of billions to one.

The Chemistry Of Immortality

The preservation process was a complex chemical dance. As the oil seeped in, it replaced the water in the skin tissues, creating a barrier against bacteria. Simultaneously, the iron-rich sediments in the cave helped replace the organic structures with minerals, a process known as phosphatization.

This unique combination meant that instead of flattening into a carbon film like most soft fossils, the skin retained its 3D shape, allowing researchers to study it layer by layer.

A Look Inside The Ancient Epidermis

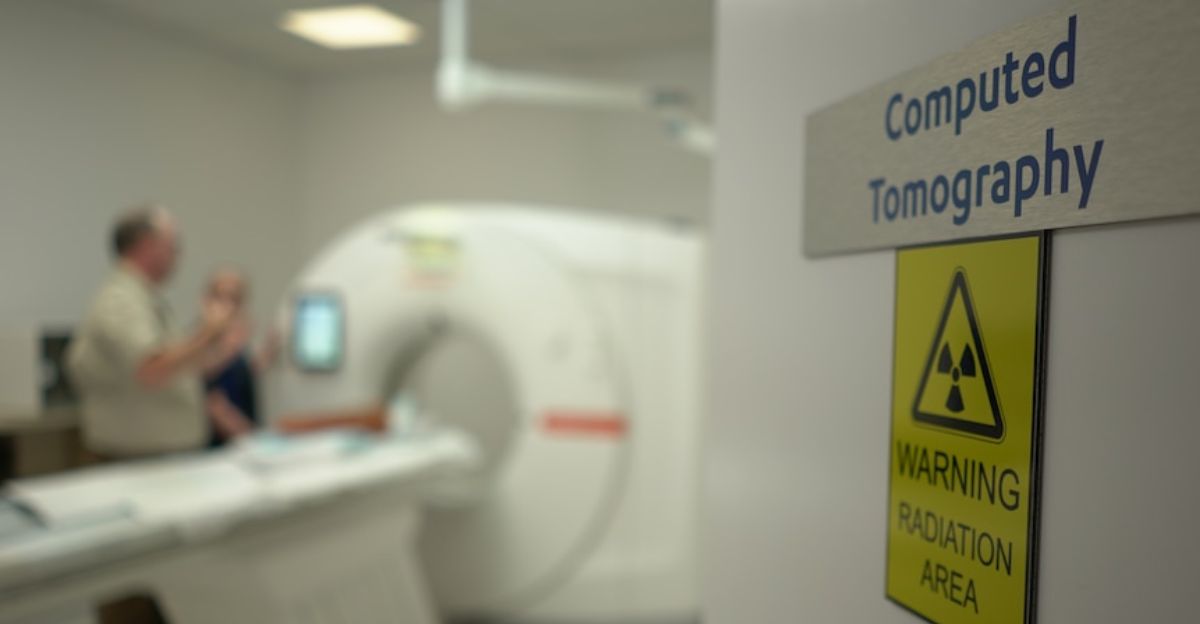

Using high-powered CT scanners, Mooney and his team didn’t just examine the fossil; they scanned through it. The scans revealed distinct layers of the epidermis, including the stratum corneum, the tough outer layer made of keratin.

This internal view confirmed that the fossil wasn’t just a surface impression but an actual preserved tissue structure, offering the first definitive proof that Paleozoic reptiles had fully terrestrialized skin identical to that of modern amniotes.

Closing The Evolutionary Gap

Before this discovery, a massive void existed in the fossil record. Paleontologists had to speculate when true reptilian skin evolved, assuming it occurred in the Permian but lacking physical evidence. The gap between this specimen and the previously oldest known skin fossil was a staggering 130 million years.

This find serves as a missing link, physically connecting the amphibious ancestors of the Carboniferous period to the fully armored reptiles of the Mesozoic era.

Armor For A Harsh World

The microscopic details tell a story of survival. The pebbled scales were not just for show; they provided armor against abrasion and, crucially, retained body moisture. In the drying climate of the Permian, this adaptation was the difference between life and death.

The discovery confirms that the “hardware” for life on land—tough, keratinized skin—was already standard equipment for early amniotes, allowing them to radiate into diverse environments away from water.

Pangea: A World In Motion

Imagine the world this creature walked upon. It was the early Permian, and the continents were colliding to form Pangea, a landmass so vast that its interior was likely an arid desert.

However, the Richards Spur region was a tropical upland, teeming with life before the devastating “Great Dying” extinction event that would eventually wipe out 90% of species. This scrap of skin is a survivor from a flourishing ecosystem that was destined for a catastrophic end.

The Long Road To Verification

Science moves slowly to ensure accuracy. While the Mays found the fossils in 2018, it took six years of testing and peer review before the findings were published in Current Biology in 2024.

The team had to rule out every other possibility, ensuring the texture wasn’t a bacterial mat or a geological oddity. As Robert Reisz noted, the result was “completely unlike anything we would have expected,” requiring absolute certainty before rewriting the history books.

Why The Date Matters

To grasp the age of 290 million years, one must look at the timeline. Dinosaurs would not appear for another 60 million years. Flowers didn’t exist. Grass didn’t exist. This skin belongs to a creature that lived closer in time to the first forests than to the Tyrannosaurus rex.

It resets the clock on vertebrate evolution, proving that the biological engineering of terrestrial skin was an early, defining triumph of the amniote lineage.

A Treasure Trove Of Ancient Life

The skin isn’t the only star of Richards Spur. The cave system has yielded thousands of fossils, including 30 different species of tetrapods, making it the richest source of early Permian fossils in the world. From tiny amphibian-like creatures to the distinctive jaws of Captorhinus, the site offers a comprehensive snapshot of the ecosystem.

The presence of such diverse life suggests that this “upland” environment was a thriving biological hotspot, now preserved in stone.

Hidden In The Oil Fields

The study raises a tantalizing possibility: are we burning other fossils? The same geological processes that create oil reservoirs—burying organic matter in anoxic conditions—are also ideal for preserving soft tissue.

Mooney suggests that other “oil trap” sites might hold similar secrets, waiting for paleontologists to examine the black, tar-soaked rocks that are usually discarded by mining operations. The “black gold” of the energy industry might be hiding the true gold of paleontology.

A Legacy Carved In Stone

Ultimately, this fingernail-sized fossil tells a story of resilience. It speaks of a lineage that ventured onto land, developed a tough skin to survive, and persisted for millions of years.

As Mooney concludes, this discovery provides a tangible connection to our deep ancestry, revealing that the protective barrier we all wear—our skin—has roots that date back to the very dawn of terrestrial life. It is a humble, wrinkled witness to the moment life truly conquered the Earth.

Sources:

- Paleozoic cave system preserves oldest-known evidence of amniote skin, Current Biology

- Rare skin fossil is oldest by 130 million years, CNN

- Fossilized, crocodile-like skin is oldest ever discovered, scientists say, NBC News

- This is the oldest fossilized reptile skin ever found, Nature

- Fossilized skin found in Oklahoma is the oldest in the world, The Oklahoman