Earth faced its most violent solar assault of 2026 when an X-class flare erupted from the sun’s surface on January 18, unleashing radiation that struck the planet at light speed. Within minutes, radio networks across the Americas went dark. Twenty-five hours later, a billion-ton cloud of magnetized plasma slammed into Earth’s protective magnetic field, triggering the strongest radiation storm in more than two decades. The event arrived years into a solar cycle scientists had predicted would be historically quiet—yet the sun continues delivering record-breaking outbursts that are forcing researchers to reconsider what they thought they knew about our star’s behavior.

A Cycle Defying Predictions

Solar Cycle 25 commenced in December 2019 with forecasters expecting the weakest period of solar activity in two centuries. The official prediction panel projected a modest peak of 115 sunspots around July 2025, then a gradual decline through the 2030s. Reality has diverged dramatically from these models. Instead of winding down, the sun has intensified its fury, producing X-class flares and earth-directed plasma eruptions at an alarming rate. The January 19 event marked the first S4-level radiation storm since October 2003, affecting satellites, aviation systems, and GPS networks worldwide. The deviation forces an uncomfortable question: if baseline cycle predictions contain this much error, what other aspects of solar behavior remain poorly understood for the decade ahead?

Instant Impacts

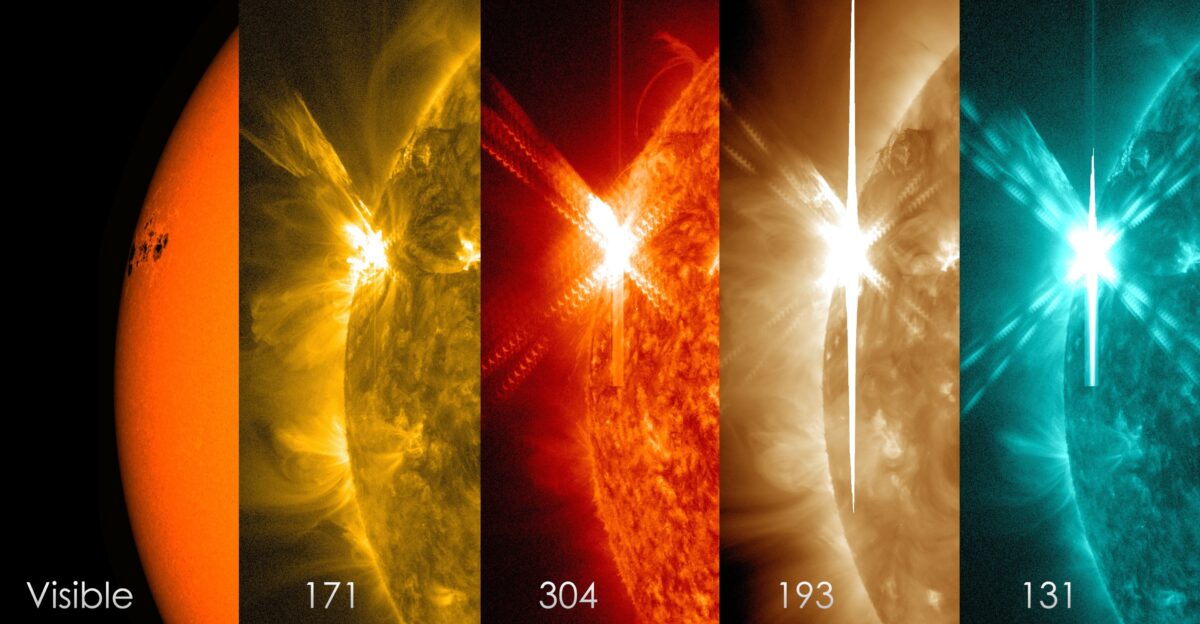

At 18:09 UTC on January 18, Active Region 4341—a magnetically unstable sunspot cluster rotating across the solar disk—detonated with an X1.9 flare, the strongest eruption of the year. The explosion released energy equivalent to thousands of nuclear weapons, accelerating subatomic particles to near-light velocity. Within seconds, X-rays and ultraviolet radiation ionized Earth’s upper atmosphere over the sunlit hemisphere. Ground stations confirmed an R3-Strong radio blackout lasting more than an hour, rendering shortwave frequencies below 10 MHz useless across Western South America, the eastern South Pacific, and portions of North America—millions of square kilometers affected simultaneously.

High-frequency radio communications experienced significant disruptions across affected regions, forcing reliance on satellite backup systems. Maritime operators in the South Atlantic and Pacific temporarily lost navigation updates and distress-signal capability. Emergency responders in Brazil, Peru, and Mexico experienced communication gaps during routine operations. While backup infrastructure prevented catastrophic failures, the incident exposed modern society’s fragility when the sun severs radio propagation in moments.

Cascading Consequences

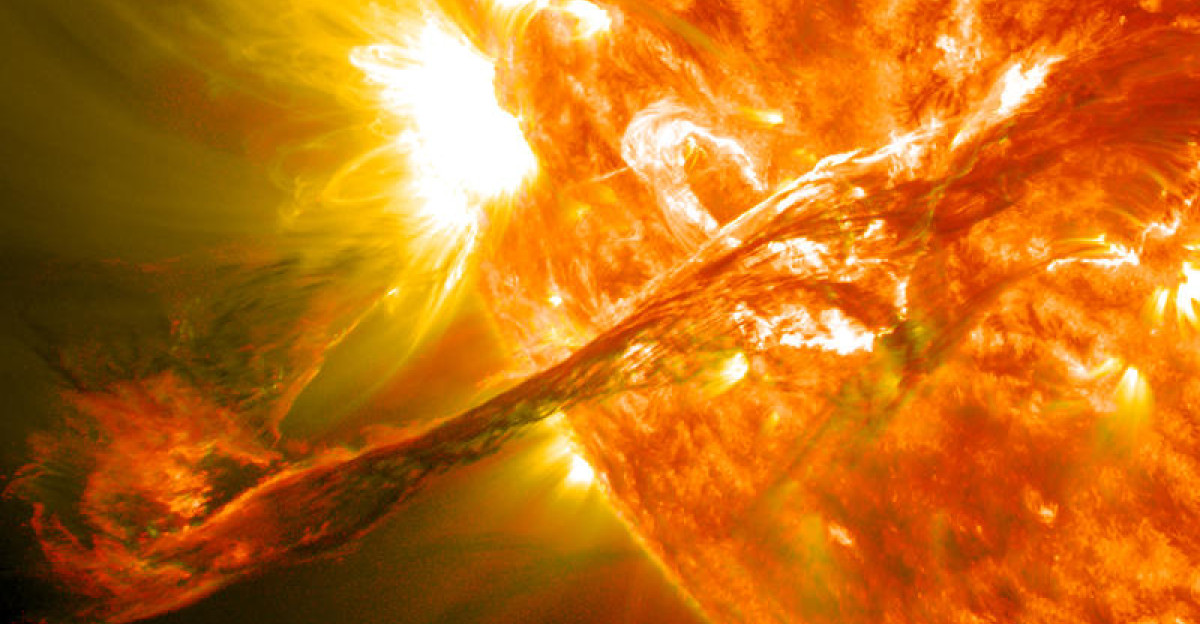

The flare ejected a full-halo coronal mass ejection—a magnetized plasma bubble ripped from the solar atmosphere and hurled toward Earth at approximately 693 kilometers per second in initial estimates, nearly double typical velocities. NOAA forecasters issued a G4 Severe Geomagnetic Storm Watch with an expected arrival window of 24 to 48 hours. The plasma refused to cooperate. At 19:38 UTC on January 19, just 25 hours after the flare, monitoring satellites detected the shock front colliding with Earth’s magnetosphere. The early impact caught operators off-guard, rapidly escalating from G3 Strong to G4 Severe conditions—the second-highest intensity on the five-point scale.

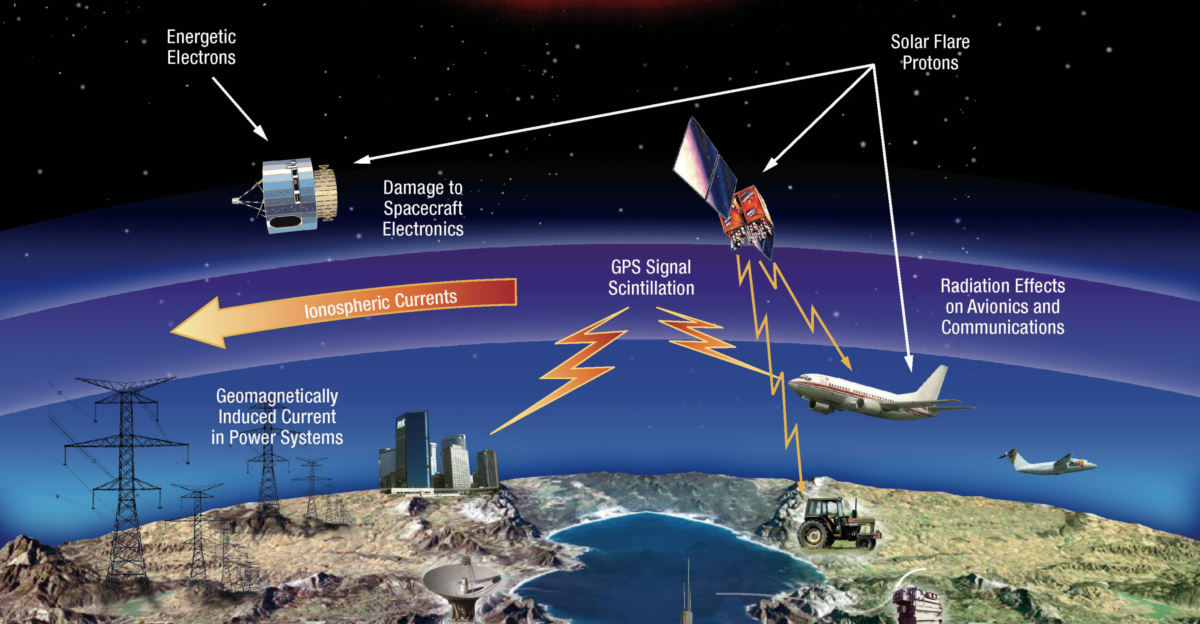

Simultaneously, a parallel catastrophe unfolded: the radiation storm reached S4 Severe intensity, the strongest since October 2003. High-energy protons penetrated satellite shielding, damaging semiconductor circuits and prompting standard radiation protection protocols aboard the International Space Station. Communications satellites reported increased transmission errors. GPS accuracy degraded across both American continents. Precision agriculture systems lost centimeter-level positioning capability, affecting farming operations reliant on GPS guidance. The cumulative economic impact measured in millions of dollars.

Power grid operators remained on high alert as elevated induced currents flowed through long transmission lines—the phenomenon that caused Quebec’s 1989 blackout during a previous geomagnetic superstorm. Engineers manually reduced reactive power and isolated redundant lines to prevent cascading failures. The threat passed, but safety margins proved uncomfortably thin. NOAA predicted auroras visible across 22 to 24 states as far south as Kansas, Oklahoma, Virginia, and parts of Texas—regions rarely witnessing such displays. Skywatchers celebrated while infrastructure operators noted warning flags.

Uncertain Path Forward

The sun remains volatile. Active Region 4341 continues rotating across the solar disk with potential for additional eruptions before disappearing from Earth view in early February. Other active regions are emerging, and solar activity is expected to stay elevated through 2026. Some researchers speculate Solar Cycle 25 may experience multiple peaks—a pattern seen in historical records but poorly understood.

If the next decade brings repeated severe storms, power grids, satellites, and communication systems designed with current threat assumptions could face inadequate protection margins. The January event proved redundancy works—no single failure cascaded into systemic collapse—but observers noted a slightly stronger storm or faster arrival might have tipped the outcome. As civilization navigates Solar Cycle 25’s uncertain trajectory, a humbling truth emerges: the sun’s moods shape technological society’s future in ways only beginning to be fully appreciated and defended against.

Sources:

NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center briefings and alerts, January 18–20, 2026

NOAA SWPC X-class Flare Reports and CME Analysis, January 18, 2026

NOAA SWPC Geomagnetic Storm Updates and Radiation Storm Reports, January 19–20, 2026

NOAA Aurora Forecast and Alerts, January 19–20, 2026

NOAA Solar Cycle Progression Reports

SpaceWeatherLive Solar Activity Database and AR 4341 Archive, January 2026