For generations, we pictured Neanderthals vanishing in fire and fury—storms, sickness, starvation, or a clash they couldn’t win. However, a new mathematical model, published in Scientific Reports, paints a far quieter, stranger ending.

It suggests Neanderthals didn’t die out at all. They blended. Their identity slowly dissolved into ours, erased not by catastrophe but by connection. It’s extinction without extinction, history rewritten not in violence, but in intimacy.

The Team Who Dared to Rethink the Impossible

This revelation comes from an unlikely trio: computational chemist Andrea Amadei of the University of Rome Tor Vergata, evolutionary geneticist Giulia Lin from Switzerland’s aquatic research institute EAWAG, and ecologist Simone Fattorini of the University of L’Aquila.

Their peer-reviewed work challenges 150 years of assumptions with a single, clean mathematical argument grounded in neutral species drift—a theory that posits evolution can shift through random genetic changes, rather than selective advantage.

A Timeline That Quietly Changes Human Origins

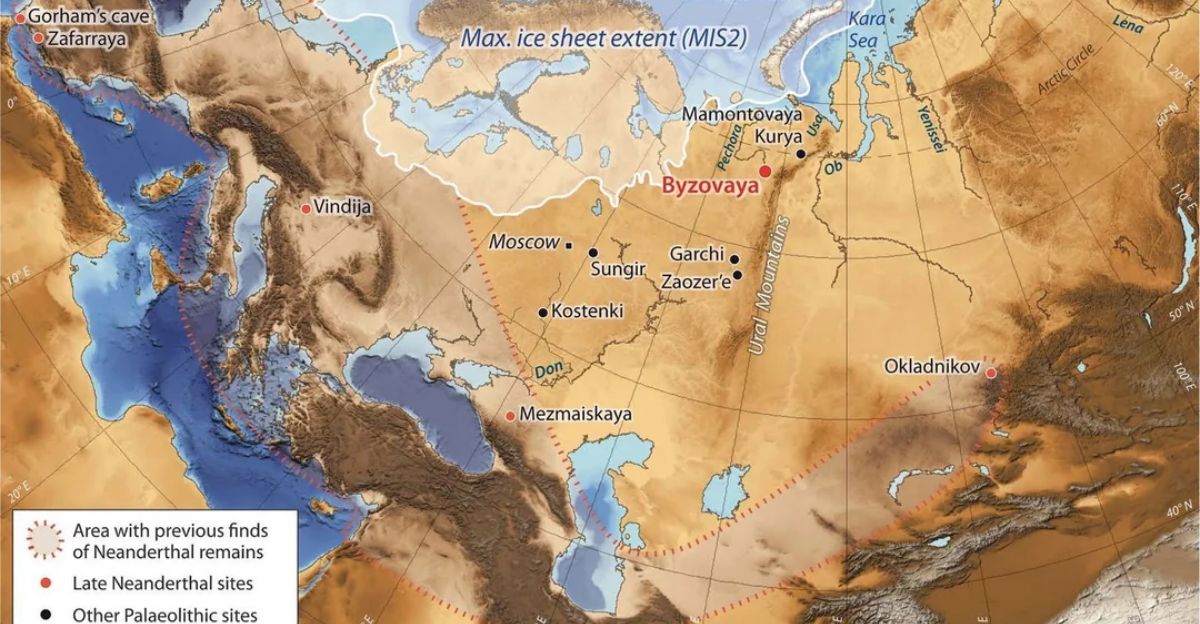

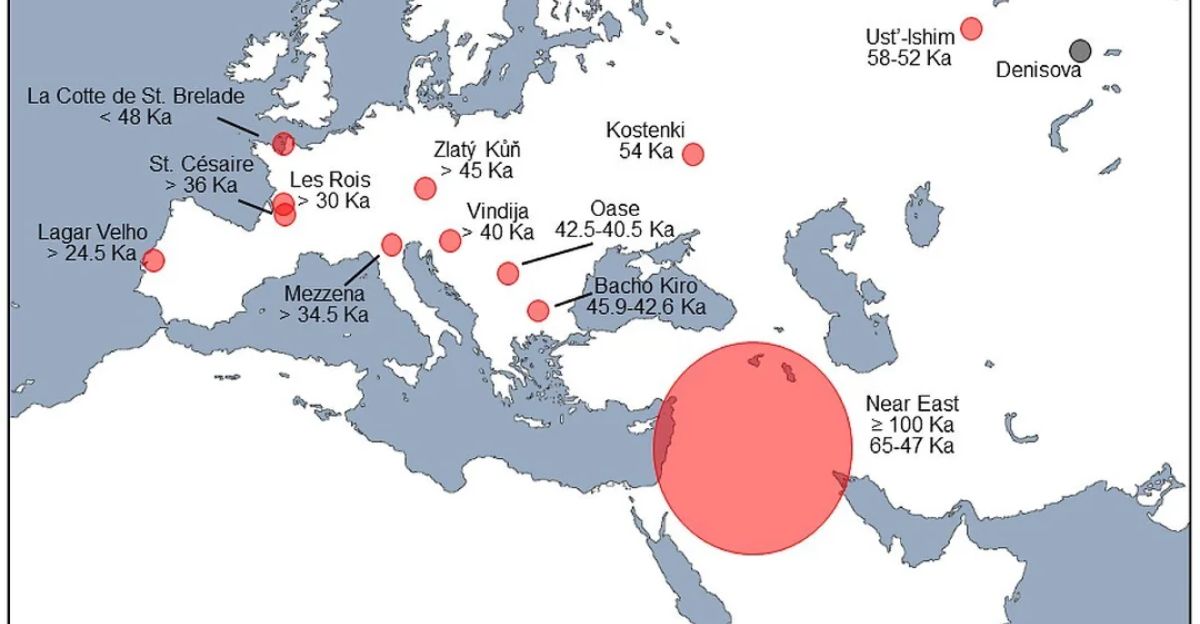

Neanderthals emerged in Eurasia roughly 400,000 years ago and dominated the region for nearly 360,000 years. Then modern humans arrived around 40,000 years ago. Conventional stories imagine conflict. But the model suggests something gentler: slow, ongoing merging.

With each small wave of Homo sapiens migration, intimate ties formed—families, alliances, shared camps. Over the course of 10,000 to 30,000 years, this steady contact gradually integrated Neanderthals into a growing human population.

The Math Behind an Unexpected Ending

At the heart of this study is a simple demographic truth. Researchers simulated cycles of human migration—small groups entering Neanderthal territories, interbreeding, and adding their genes into the mix. No advantages required. No “superior” species. Just numbers.

A larger, more connected population gradually blended into a smaller, isolated one. With every generation, Neanderthal genetic identity thinned until it became statistically invisible. Extinction by arithmetic, not apocalypse.

A Theory That Removes Disaster From the Equation

Perhaps the most radical claim is what the model doesn’t need. It doesn’t call for climate collapse, epidemics, resource scarcity, or violent conquest. It shows that interbreeding alone—steady, generational, unforced—could erase a species’ genetic individuality.

As the authors put it, sustained gene flow from a larger population was enough. Human evolution’s great twist may be that the quietest mechanism was the most powerful.

A Farewell That Took Thousands of Years

Instead of a dramatic final chapter, picture a long fade-out. Neanderthal identity didn’t vanish in a single moment—it diluted over countless generations. Hybrid communities likely flourished, raising families whose ancestry shifted slightly with each birth.

Over 10,000 to 30,000 years, the “pure” Neanderthal genome thinned into statistical silence. The last true Neanderthal may have died naturally, surrounded not by enemies, but by descendants who were already becoming us.

The Genetic Ghosts Living in Modern Bodies

Yet Neanderthals didn’t disappear. Their DNA lives on—tucked inside nearly every person of European or Asian descent. Modern humans carry about 1–4 percent Neanderthal DNA, according to current genetic research. These aren’t random genetic leftovers.

They influence immunity, brain development, metabolism, and even our response to certain diseases. Pieces of their biology shape our biology. They vanished as a people, but not as a presence.

A Species Hidden in Billions of Modern Genomes

The paradox is remarkable: an extinct species that remains biologically immortal. Billions of people alive today carry sequences inherited from Neanderthals who walked Eurasia 40,000 to 50,000 years ago. In genetic terms, they never actually died out—they merged.

Their identity dissolved, but their biological imprint endures. They became an invisible lineage inside us, more alive in our chromosomes than in any fossil bed.

A Replacement Timeline That Feels Human, Not Violent

The model’s 10,000-to-30,000-year replacement window reshapes the world we imagine. Modern humans didn’t storm in; they trickled in. Neanderthal communities likely met newcomers through trade, shared tools, intermarriage, cooperation, and slow cultural blending.

Some regions probably mixed rapidly. Others maintained Neanderthal-heavy ancestry for millennia. Replacement wasn’t an event—it was a rhythm of human movement, relationship, and gradual demographic change across an immense span of time.

How This Challenges Every Old Theory

Does this model wipe away other extinction theories? Not necessarily. Climate instability, disease, and resource challenges may still have played supporting roles. But the crucial shift is this: none of those forces were required for Neanderthals to disappear. Genetic dilution alone was sufficient.

The researchers emphasize this gently but firmly—the disappearance wasn’t necessarily catastrophic. It may have been demographic, relational, and slow.

Why Immigration Waves Mattered More Than Invasions

Instead of one massive migration, the model envisions repeated small-scale waves of Homo sapiens arriving every few decades. Each wave added dozens to hundreds of newcomers who intertwined with local Neanderthal communities.

Across thousands of years, these hundreds or thousands of immigration cycles steadily nudged the genetic balance toward modern humans. Not an invasion—an accumulation. Not conquest—connection.

The Population Puzzle Behind Their Vulnerability

Why were Neanderthals so susceptible to dilution despite thriving for hundreds of millennia? Their populations were small and scattered—pockets of communities separated by mountains, glaciers, and long distances. Small populations experience stronger genetic drift. Modern humans, by contrast, traveled farther, forged wider networks, and reproduced in larger numbers.

Neanderthals weren’t outmatched intellectually or physically—they were outnumbered in the long game of demographics.

The Gifts Neanderthals Left in Our DNA

The DNA Neanderthals left behind isn’t trivial. Some variants bolster immune responses. Others improve fat storage, bone strength, or adaptation to cold. Certain neurological traits also trace back to them.

Natural selection preserved these genes because they helped early modern humans survive in Eurasia’s harsh climates. The merger between species wasn’t one-sided; both lineages contributed to the emerging human story.

A Century of Evolutionary Theory Turned Upside Down

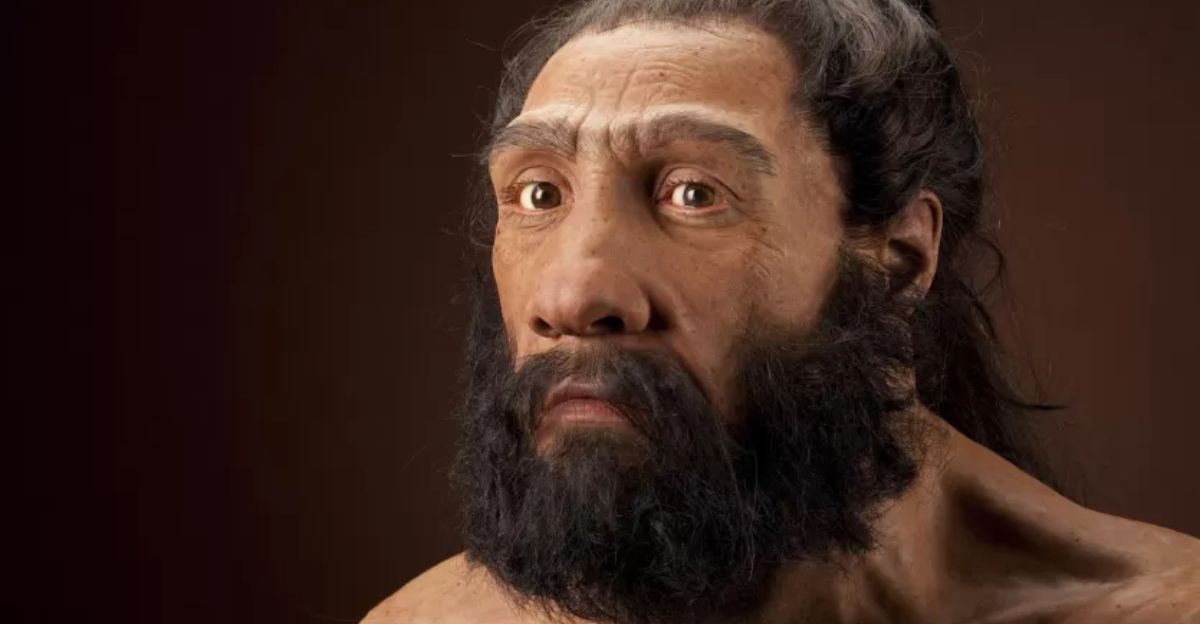

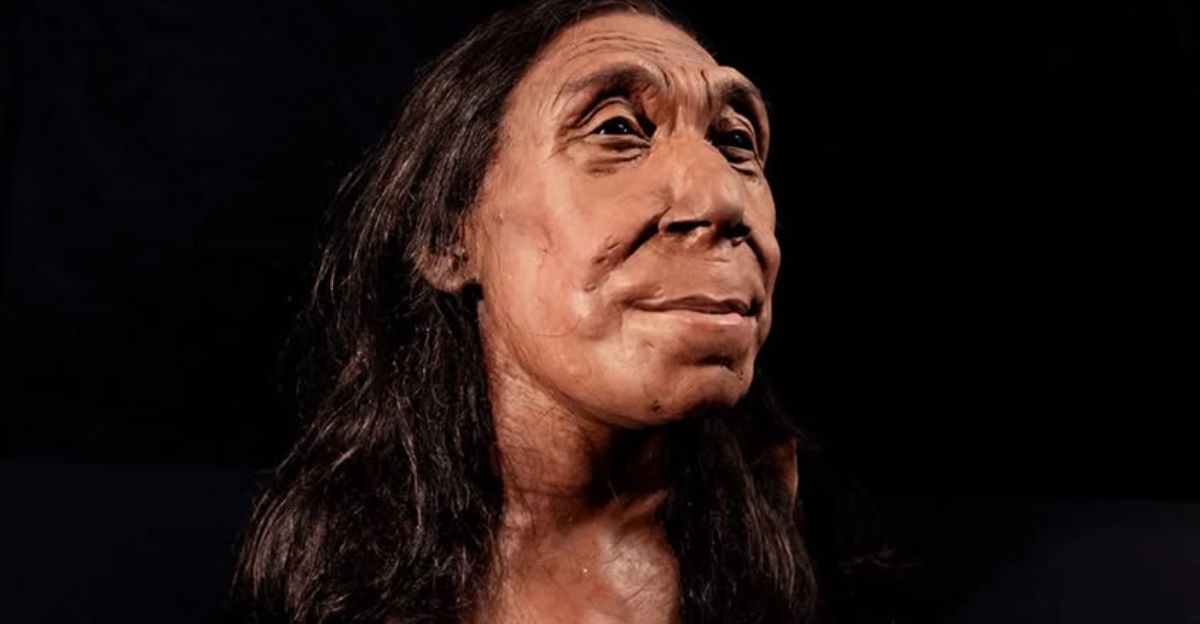

Since Neanderthal fossils were discovered in Germany in 1856, scientists have developed theories of human superiority—encompassing better tools, sharper minds, and faster innovation. But the new model resists triumph narratives.

It suggests that the two species weren’t rivals but rather compatible partners, whose interbreeding was natural, sustained, and ultimately transformative. Neanderthals didn’t “lose.” They blended into a shared humanity that still carries their echo.

Hybrids Who Thrived, Not Struggled

Archaeology confirms this blending wasn’t rare or harmful. The remains of hybrid individuals reveal healthy, robust bodies capable of surviving and reproducing successfully. Their existence proves the species were genetically close—close enough for interbreeding to be ordinary, not exceptional.

In this context, mixing becomes not a footnote, but the central mechanism by which Neanderthals lived on.

The Modern Echo for Small Populations Today

The study raises a modern parallel: small, isolated populations today face similar demographic pressures. In a world of mass migration and cultural blending, distinct genetic identities can fade not through force, but through intermarriage and demographic imbalance.

The Neanderthal model reminds us that cultural and genetic distinctiveness can dissolve quietly across generations, a powerful insight with both scientific and ethical implications.

The Strange Line Between Extinction and Immortality

What does it mean for a species to go extinct if its DNA survives in billions of people? Neanderthals are biologically present but culturally gone—a vanished people whose genetic legacy thrives. Their extinction becomes a transformation rather than an ending.

They’re not absent; they’re absorbed. The boundary between species, lineage, and identity is more porous than textbooks once allowed.

Peer Review Gives the Model Weight

The study underwent peer review and was published in Scientific Reports—a respected Nature group journal—in November 2025. That doesn’t make the model unassailable, but it signals that its assumptions and mathematics held up under expert scrutiny.

It’s a hypothesis the scientific community now takes seriously, adding new momentum to discussions about how human history unfolded.

The Questions That Still Haunt the Field

Even with this model, mysteries remain. Where were the hotspots of interbreeding? Why did some regions show faster genetic turnover? How did environmental shifts shape population movement? And why were modern humans ultimately more prolific?

The model provides a mechanism for genetic absorption but doesn’t yet explain every demographic pattern. The puzzle is clearer, but incomplete.

A New Story of How We Became Human

This research reframes human origins. Our past wasn’t forged solely through competition, conquest, or catastrophe. It emerged through mingling—slow, intimate, generational. Neanderthals didn’t fall; they folded into us. Their story isn’t one of defeat but of transformation.

Their genes, their resilience, their evolutionary gifts all live on inside modern humanity. The great shift of prehistory wasn’t a battle. It was a merging that still shapes who we are today.