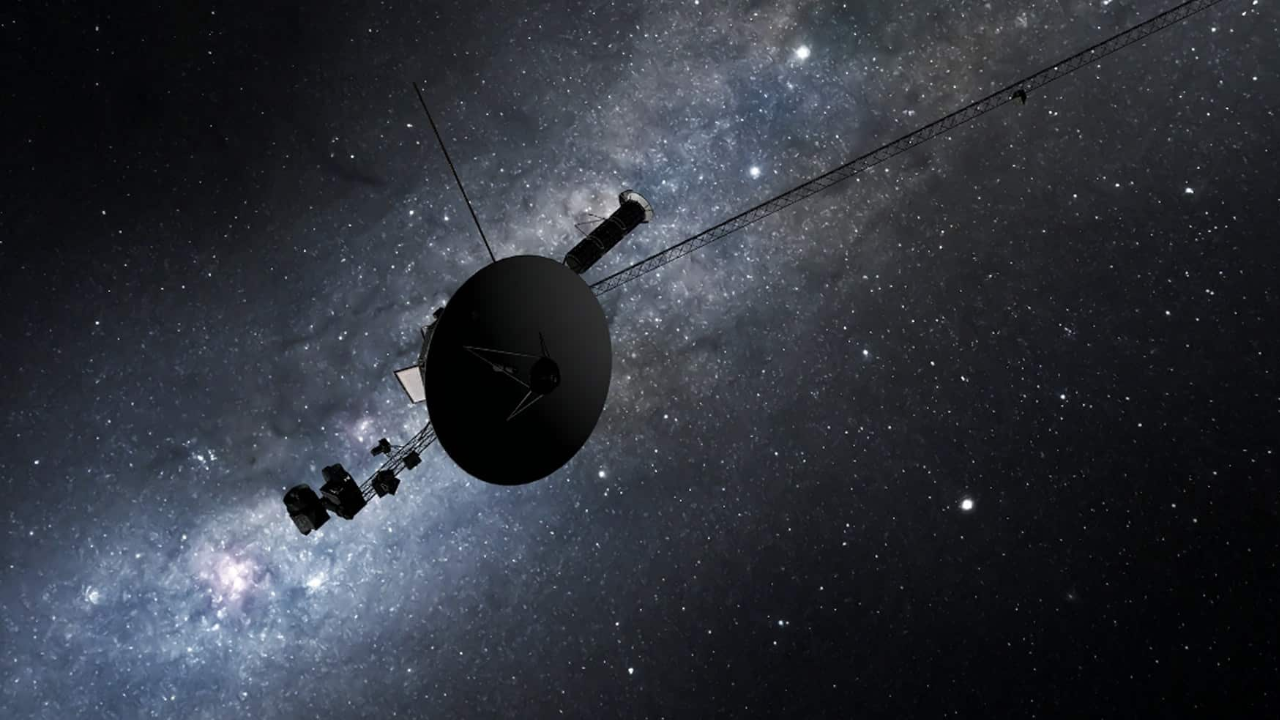

Voyager 1 is the most distant human-made object, and it is now so far away that talking to it is becoming painfully slow. Over the next year, it will reach a distance where a radio signal from Earth will take a full day to arrive, forcing the spacecraft to act more and more on its own.

A Tiny Spacecraft In A Huge Distance

Voyager 1 launched in 1977 using technology far weaker than what sits in a typical smartwatch today. Yet it has traveled more than 25 billion kilometers (about 15.7 billion miles) from Earth, making it humanity’s farthest “ambassador” in space. By November 2026, it is expected to be about one light-day away from Earth, meaning a message will need 24 hours to get there and another 24 hours to come back. At that distance, engineers can no longer adjust things in real time; every decision must be planned far in advance.

Voyager 1 exists because of a rare alignment of the outer planets that happened in the late 1970s and will not repeat until the 22nd century. This lineup allowed NASA to send the twin Voyagers past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune with less fuel by using gravity assists. The spacecraft were built with extra-strong parts and backup systems, but no one realistically expected them to still be working almost 50 years later. Their ongoing survival shows just how robust their design was.

Crossing The Sun’s Invisible Edge

The Sun blows a stream of charged particles outward, forming a giant bubble around the solar system called the heliosphere. The outer skin of this bubble, where the solar wind meets interstellar space, is known as the heliopause. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft to cross this boundary and truly enter interstellar space, with Voyager 2 following in 2018. As they passed through, the probes detected a thin region of superheated plasma, with temperatures between about 30,000 and 50,000 Kelvin, much hotter than scientists had expected.

This “wall” of hot plasma did not destroy Voyager 1 because the gas there is incredibly thin, with very few particles to actually heat the spacecraft. Voyager 1 also measured changes in particle density and magnetic fields that showed it had moved from the Sun’s environment into interstellar space. One surprise was that the magnetic field direction outside the heliopause was still roughly aligned with the Sun’s field, which challenged some earlier predictions. These results helped scientists refine their models of how our solar system interacts with the wider galaxy.

Talking To A Fading Machine

Communicating with Voyager 1 requires some of the largest radio antennas on Earth, part of NASA’s Deep Space Network in California, Spain, and Australia. The signal that reaches these antennas is incredibly weak, far below the power of a household light bulb, and must be carefully filtered out of background noise. As of late 2025, it already takes nearly 24 hours for a one-way signal to travel between Earth and the spacecraft. Once Voyager 1 is exactly a light-day away, engineers will have to accept that every new command will take two days to send and confirm at minimum.

Keeping the spacecraft pointed at Earth is another challenge because its thrusters are old and have built up residue over decades of use. Engineers have periodically switched to backup thrusters that had been idle for many years, carefully warming and firing them to save the mission. These efforts are risky but necessary to keep the antenna aligned so the faint signal can reach Earth. Any long outage at one of the big antennas, such as during upgrades in Australia, makes this pointing problem even more stressful for the team.

Power Running Low, Legacy Growing

Voyager 1 gets its electricity from three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) powered by plutonium-238, which produces heat that is turned into electrical power. The output of these RTGs drops by about 4 watts every year as the radioactive fuel decays and components age. To keep the spacecraft operating, NASA has been turning off heaters and instruments one by one, keeping only the most important science tools running. Some instruments, such as a cosmic ray detector on the twin mission, have already been shut down to stretch the remaining power.

Sometime in the early 2030s, the RTGs will no longer be able to power the radio transmitter, and Voyager 1 will fall silent. Even after that, the spacecraft will continue to coast through interstellar space for millions of years, long after any current mission team is gone. It carries a golden record with sounds and images from Earth, meant as a message for any possible distant civilization that might someday encounter it. The mission’s long life and increasing independence are shaping how engineers design future probes to places like distant moons and deep space, where spacecraft must handle many problems on their own.

Sources

Ecoticias – “Voyager 1 finds wall of fire at 90,000 ºF”

Karmactive – “NASA’s Voyagers Navigate 90000°F ‘Wall of Fire’

SciTechGen – “NASA’s Voyager Spacecraft Found A ‘Wall’ At The Edge Of Our …”

Economic Times – “Voyager hits a ‘Wall of Fire’: NASA probe finds a furnace at the edge …”