Scientists have built one of the most detailed forecasts ever of Earth’s deep future, and it comes with a stark warning: the air that makes life possible has a built‑in expiry date. By combining climate, chemistry, and solar physics, researchers show that Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere will probably last for roughly another billion years before undergoing a rapid and dramatic decline.

This timescale may sound vast, but on the scale of planetary history it means we are already living in the later chapters of Earth’s habitable story. The findings suggest that while Earth itself will endure, the breathable conditions that support animals, plants, and people are more fragile and time‑limited than previously believed.

The Team Behind the Prediction

This work is led by Kazumi Ozaki, an environmental scientist at Toho University, together with U.S. collaborator Christopher Reinhard of the Georgia Institute of Technology and NASA‑affiliated planetary researchers. Their expertise spans geochemistry, climate science, and the study of how stars evolve, allowing them to link slow changes in the Sun to equally slow but decisive shifts in Earth’s air.

Ozaki describes the project as an effort to answer a deceptively simple question: “It remains unclear exactly when and how” Earth’s oxygen will disappear, despite long‑standing expectations that the biosphere must eventually end.

From Lab to Landmark Journal

The study, titled The future lifespan of Earth’s oxygenated atmosphere, appears in the respected journal Nature Geoscience, signifying strong peer review and scientific scrutiny. In it, the authors outline a combined climate and biogeochemical model that simulates how oxygen, carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases evolve as the Sun slowly brightens over time.

They conclude that Earth’s atmosphere will remain oxygen‑rich, above just 1 percent of today’s levels for an average of about 1.08 billion more years, with an uncertainty of roughly 140 million years. That number comes from running the model hundreds of thousands of times, each with slightly different conditions, to capture the full range of plausible futures.

What 400,000 Supercomputer Runs Reveal

To reach their conclusions, the team carried out around 400,000 separate supercomputer simulations, each representing a different possible future for Earth’s climate and biosphere. In every run, the model tracked how sunlight, volcanic gases, rock weathering, and biological activity interact to shape the atmosphere over billions of years.

This huge ensemble allowed the scientists to identify robust patterns that appear regardless of small changes in starting conditions or parameters. One key pattern is a sharp drop in oxygen once carbon dioxide falls below the minimum needed for photosynthetic life, effectively cutting off the main source of new oxygen. The researchers found that, on average, oxygen levels remain high for about 20 to 30 percent of Earth’s total habitable lifetime before collapsing.

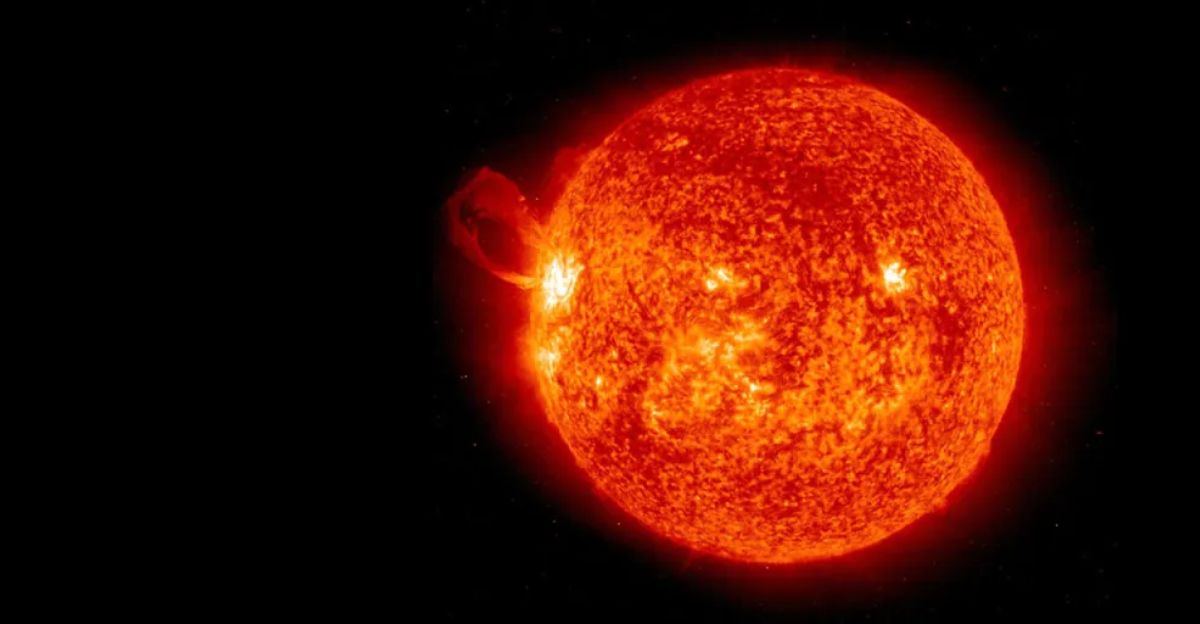

The Sun Slowly Turns Up the Heat

The villain in this story is not an asteroid or a supervolcano, but the Sun itself. As the Sun ages, its core contracts and its energy output steadily rises, sending slightly more radiation to Earth with each passing hundred million years. This extra energy speeds up the chemical weathering of rocks on land, a process that pulls carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and locks it away as minerals.

At first, that could seem like a cooling benefit, but over the very long term, the Sun’s brightening overwhelms any cooling from falling carbon dioxide. More importantly for life, carbon dioxide is the raw material plants use for photosynthesis; when levels drop too low, they can no longer make enough food or oxygen to survive.

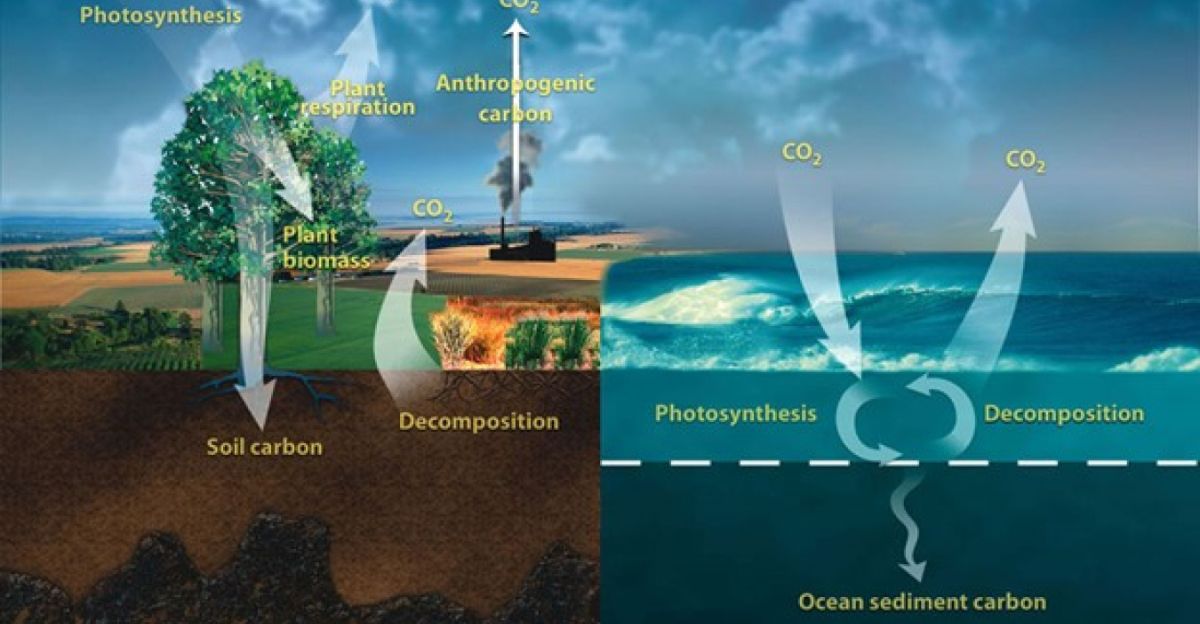

When the Carbon Cycle Breaks

Right now, Earth’s carbon cycle acts as a balancing system, moving carbon between air, oceans, soil, and rocks in ways that support a stable, oxygen-rich atmosphere. Plants and algae absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, while processes like respiration and decomposition return carbon dioxide to the air.

As the Sun brightens and chemical weathering intensifies, more carbon dioxide is stripped from the atmosphere and stored in rocks, eventually driving atmospheric carbon dioxide to extremely low levels. Once carbon dioxide falls below the threshold needed for photosynthesis, plants and photosynthetic microbes cannot survive at large scales, leading to a massive crash in global oxygen production.

The Countdown to “Great Deoxygenation”

Once large‑scale photosynthesis collapses, oxygen does not fade gently, it plunges. The models predict that after a long stable period, atmospheric oxygen will drop by several orders of magnitude in a geologically short time, returning to levels more like early Earth before the first big rise in oxygen about 2.4 billion years ago.

Ozaki and colleagues call this rapid transition “future deoxygenation” and argue it is an inevitable consequence of rising solar flux and declining carbon dioxide. “The atmosphere after the great deoxygenation is characterized by elevated methane, low-levels of CO2, and no ozone layer,” Ozaki notes, describing a fundamentally altered world.

Faster Deadline Than Earlier Estimates

For years, many scientists assumed that Earth’s oxygen-rich conditions would persist for around two billion more years, roughly matching earlier climate projections tied to the Sun’s evolution. The new study cuts that comfortable margin in half, suggesting that high oxygen levels are likely to last for only about one more billion years on average.

Ozaki’s team calculates a mean remaining lifespan of 1.08 billion years for an atmosphere with more than 1 percent of today’s oxygen concentration, plus or minus 140 million years. That tighter timeline reveals that oxygen-rich windows on habitable planets may be surprisingly short, even if the planet itself remains in the so‑called habitable zone where liquid water can exist.

Why Complex Life Cannot Adapt

Complex life, animals, plants, and eventually humans, evolved in an atmosphere where oxygen makes up about 21 percent of the air. These organisms depend on high oxygen levels to fuel energy‑hungry bodies and brains; big, active creatures cannot survive in the thin, oxygen-poor air envisioned in the distant future.

When photosynthetic organisms die back, there is no mechanism left to replenish oxygen at anything close to current levels, so existing ecosystems slowly unravel. The study’s authors argue that the sharp drop in oxygen will be “the primary cause” of an extinction event that wipes out complex aerobic life, even if some microbes endure.

Microbes as the Last Survivors

Even after the air becomes unbreathable for animals, some microbial life is expected to persist. These survivors will likely include extremophiles, microorganisms that thrive in low‑oxygen, methane‑rich, or high‑radiation environments similar to early Earth. The study suggests that the post‑oxygen atmosphere will be rich in methane and largely devoid of ozone, yet still habitable for certain anaerobic microbes that do not rely on oxygen for metabolism.

“The Earth system will probably be a world of anaerobic life forms,” Ozaki says, describing a biosphere that looks more like the planet 3 billion years ago than the one humans know today. In this future, microbial mats, subsurface communities, and perhaps deep‑ocean or underground ecosystems may carry on long after forests, coral reefs, and mammals have vanished.

Earth Returns to a Methane World

As oxygen disappears, methane, a powerful greenhouse gas produced by certain microbes will rise to levels thousands of times higher than today’s. With little or no ozone layer left to filter ultraviolet light, the atmosphere could develop a thick, hazy photochemical smog, giving the sky an orange tint reminiscent of Saturn’s moon Titan.

This new atmosphere would let harmful ultraviolet radiation pour down onto the surface, sterilizing many environments that might otherwise support life. Surface waters, soils, and exposed land would be harsh territory, while any remaining life would need to find refuge below ground, underwater, or within protective biofilms.

Oceans as Earth’s Temporary Buffer

Earth’s oceans are expected to act as a temporary buffer, soaking up heat and moderating some of the early impacts of the Sun’s brightening. As solar radiation increases, the oceans absorb more energy, slowing the pace at which surface temperatures rise and delaying some atmospheric tipping points.

However, models of Earth’s long‑term climate indicate that this buffer has limits: eventually, higher temperatures will cause more water to evaporate into the atmosphere, adding water vapor, a potent greenhouse gas that accelerates warming. Over very long timescales, this process moves Earth toward a “moist greenhouse” state, where significant amounts of water are lost to space.

A Slow Suffocation, Not a Sudden Catastrophe

Unlike an asteroid impact or supervolcanic eruption, this extinction story unfolds almost silently across eons. Forests thin as carbon dioxide levels sink too low to sustain them, photosynthetic organisms die back, and oxygen levels begin to slide on timescales that dwarf human history. The tipping point itself, however, is abrupt in geological terms: once carbon dioxide drops below a critical threshold, the atmosphere undergoes a rapid transition from oxygen‑rich to oxygen‑poor.

The researchers describe this as a “rapid deoxygenation” and an “abrupt shift” reminiscent of Earth’s Archean past. Ozaki has characterized the change as a sharp break in the system, warning that atmospheric equilibrium can appear stable right up until it crosses an unseen line.

The Shrinking Window for Habitability

One of the study’s most striking ideas is that Earth’s “habitability window” is not a fixed property but a narrowing slice of time. Although the planet may remain in the classical habitable zone for billions of years, the period when it has both liquid water and high oxygen appears much shorter, perhaps only 20 to 30 percent of its total habitable lifespan.

That means the conditions that support complex, oxygen‑breathing life are temporary even on a world that otherwise stays orbitally and thermally suitable for life. The authors argue that this has profound implications: many Earth‑like planets may spend only a fraction of their lives in an oxygen‑rich state that would be easily detectable with telescopes.

Rethinking Earth’s “Expiry Date” and Our Future

For decades, it was common to assume that life on Earth might adapt indefinitely, so long as the Sun allowed liquid water to exist. This new research overturns that assumption, showing that oxygen-based biospheres have a much tighter deadline, set by the slow interplay of the Sun, rocks, and living systems.

If oxygen can rise and fall so dramatically, detecting it in another planet’s atmosphere may tell astronomers that life exists there now, but not for how long. For humanity, the one‑billion‑year timescale means there is no immediate threat, yet the study deepens long‑term questions about whether advanced civilizations must eventually leave their home worlds or engineer new kinds of ecosystems.

Sources:

Nature Geoscience, The future lifespan of Earth’s oxygenated atmosphere, 2 March 2021

NASA Astrobiology, The Future of Earth’s Oxygen, 9 March 2021

Toho University, Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere will probably last for approximately one billion years, 2 March 2021

EurekAlert!, How much longer will the oxygen-rich atmosphere be sustained on Earth?, 1 March 2021

New Scientist, Most life on Earth will be killed by lack of oxygen in a billion years, 2021

Tech Explorist, The study suggests the end of the Earth will happen due to…, 6 May 2025