Imagine a car-sized robot launched before you were born. That’s Voyager 1. It left Earth in 1977 and is still sending messages home. With computers less powerful than a modern watch and powered by leftover heat from plutonium, this spacecraft has become humanity’s most distant ambassador.

It’s traveled 15.7 billion miles and keeps going, facing deadly radiation and crushing cold that would destroy almost anything else.

When Messages Take a Full Day

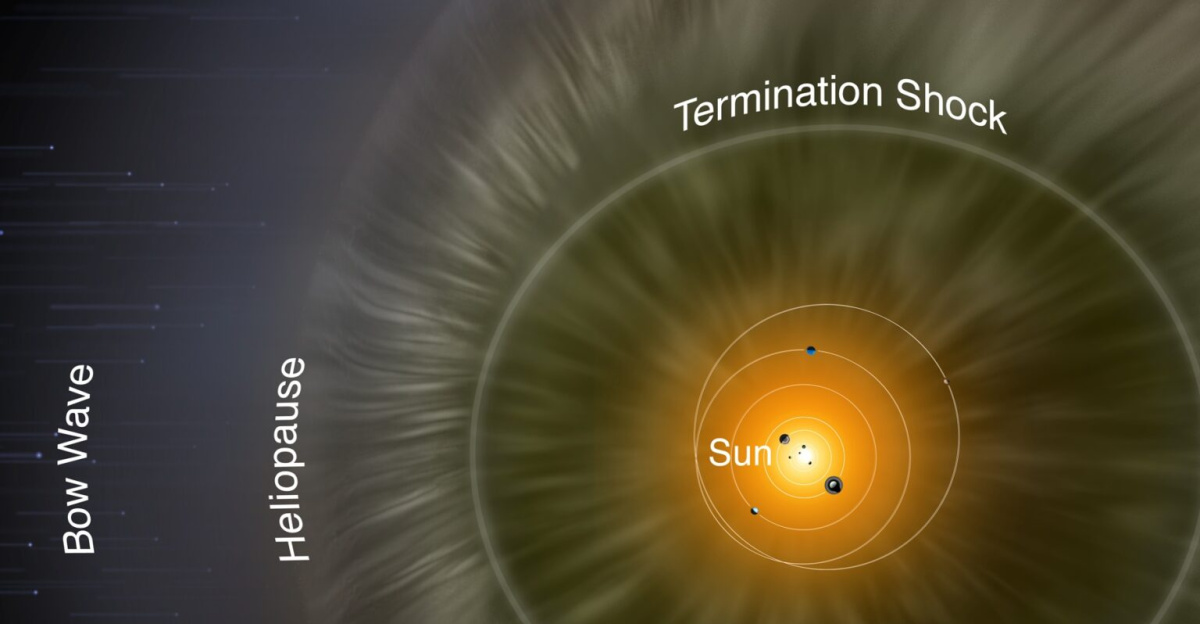

![This image shows the locations of Voyagers 1 and 2. Voyager 1 is traveling a lot and has crossed into the heliosheath, the region where interstellar gas and solar wind start to mix.<br><br>

<p>Suggested for English <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:alternative_text_for_images" class="extiw" title="en:Wikipedia:alternative text for images">Wikipedia:alternative text for images</a>: orange area at left labeled Bow Shock appears to compress a pale blue oval-shaped region labeled Heliosphere extending to the right with its border labeled Heliopause. A central dark blue circular region is labeled Termination Shock with the gap between it and the Heliosphere labeled Heliosheath. Centred in the blue region is a concentric set of ellipses around a bright spot with two white lines curving away from it: the upper line labeled Voyager 1 ends outside the dark blue circle; the lower line labeled Voyager 2 appears inside.

</p>

Remark: This picture is from 2005. Today (3 October 2018) <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_1" class="extiw" title="w:Voyager 1">Voyager 1</a> is well beyond the <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heliopause" class="extiw" title="w:Heliopause">Heliopause</a> and <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_2" class="extiw" title="w:Voyager 2">Voyager 2</a> is about to cross the Heliopause soon (see <a href="//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PIA22566-VoyagerProgram%26Heliosphere-Chart-20181003.jpg" title="File:PIA22566-VoyagerProgram&Heliosphere-Chart-20181003.jpg">the latest "3 October 2018" image</a>).<sup id="cite_ref-NASA-20181005_1-0" class="reference"><a href="#cite_note-NASA-20181005-1"><span class="cite-bracket">[</span>1<span class="cite-bracket">]</span></a></sup> Further, there has been evidence that the Bow Shock does not exist; whether the Heliosheath has this long of a tail is doubtful, too. It might be almost spherical.](https://aws-wordpress-images.s3.amazonaws.com/ruckus/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/voyager-1-entering-heliosheath-region-cropped-1.jpg)

Right now, if NASA sends a command to Voyager 1, it takes nearly 24 hours to arrive. When the spacecraft sends back an answer, it takes another 24 hours. By November 2026, the wait will be exactly 24 hours one way.

This might sound like a small number, but it changes everything about how humans control a spacecraft. Real-time control becomes impossible. The spacecraft must become truly independent, thinking for itself millions of miles away. Voyager 1 will be so far away that conversations with Earth will take two full days to complete.

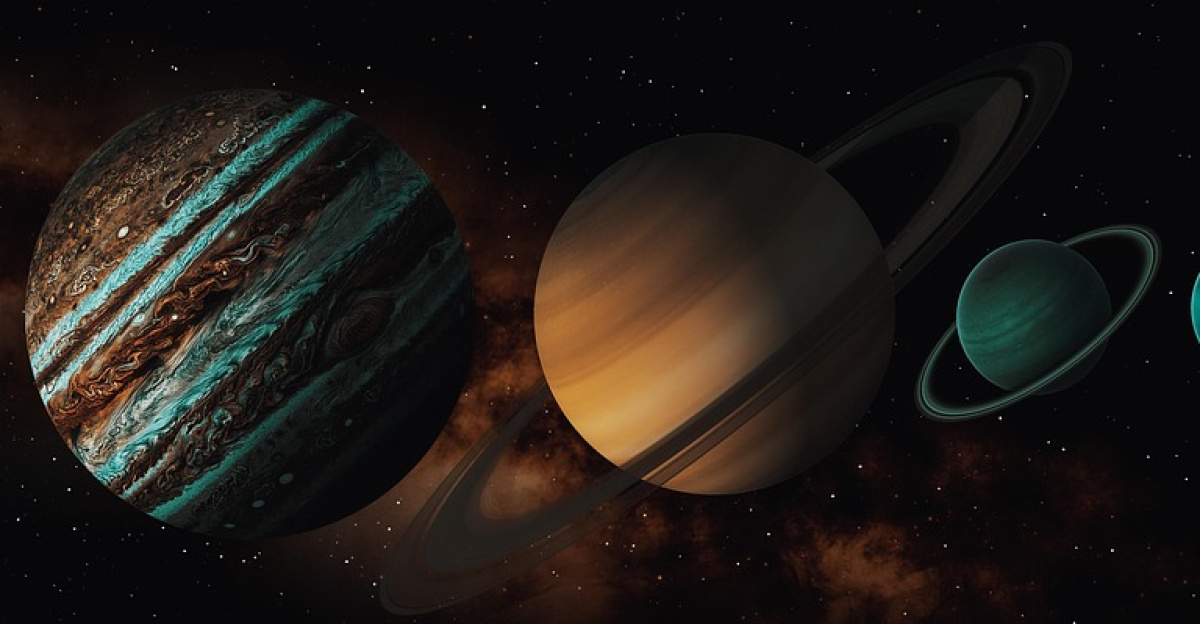

A Chance That Comes Once Every 176 Years

Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune lined up perfectly in 1977, an arrangement that won’t happen again until the year 2153. NASA built two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, to catch this rare cosmic opportunity.

Engineers packed them with backup systems and made them tough enough to survive decades in space, but nobody really believed they’d still be working in 2025. Yet here we are, nearly 50 years later, still getting messages from the robots that seized that once-in-a-lifetime chance.

Leaving the Sun’s Protective Bubble

Imagine the Sun as a protective bubble surrounding our solar system. This bubble, called the heliopause, shields us from cold, empty interstellar space. In 2012, Voyager 1 broke through that barrier, becoming the first human-made object to leave home. Voyager 2 followed in 2018.

What they found surprised everyone, extreme temperatures, strange magnetic fields, and regions nobody had predicted. The Voyagers were sending back data from a place humans had only imagined in science fiction.

Marking the One-Light-Day Milestone

Around November 15, 2026, Voyager 1 will reach a distance where light itself, the fastest thing in the universe, takes exactly 24 hours to travel from Earth. This moment, called reaching one light-day, represents more than just a number.

It’s a threshold that fundamentally changes the mission. Every command becomes a decision made in darkness, waiting a full day for acknowledgment. Engineers must pre-program solutions and trust the spacecraft to solve problems on its own.

Earth’s Lifeline to the Distant Probe

Three massive radio dishes in California, Spain, and Australia are the only way NASA stays connected to Voyager 1. These facilities capture signals so faint they’re almost impossible to detect. One dish in Australia, 230 feet wide, went offline for important upgrades from May 2025 to February 2026.

This timing created a nerve-wracking period when the spacecraft’s thrusters needed to keep its antenna pointed at Earth, were also failing. It was a race against time to save the mission before communication went dark.

Waking Up 20-Year-Old Backup Thrusters

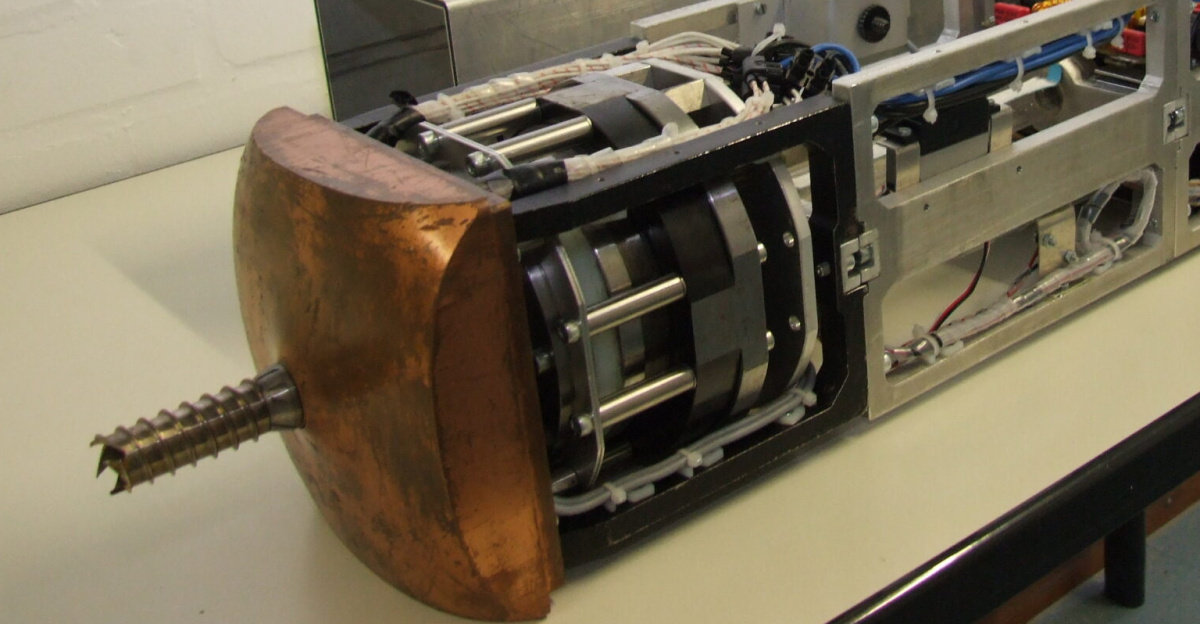

Voyager 1’s main thrusters had been blocked by chemical residue since 2004, unable to aim the antenna at Earth. NASA engineers faced a choice: accept mission failure or attempt an extreme gamble. They decided to restart backup thrusters that hadn’t fired in over 20 years.

On March 20, 2025, engineers sent the command and held their breath. When the thrusters suddenly blazed to life, heater temperatures spiking exactly as predicted, the entire mission team erupted in celebration. That single moment, broadcast live from mission control, proved that sometimes brilliant engineering and bold thinking can accomplish the impossible.

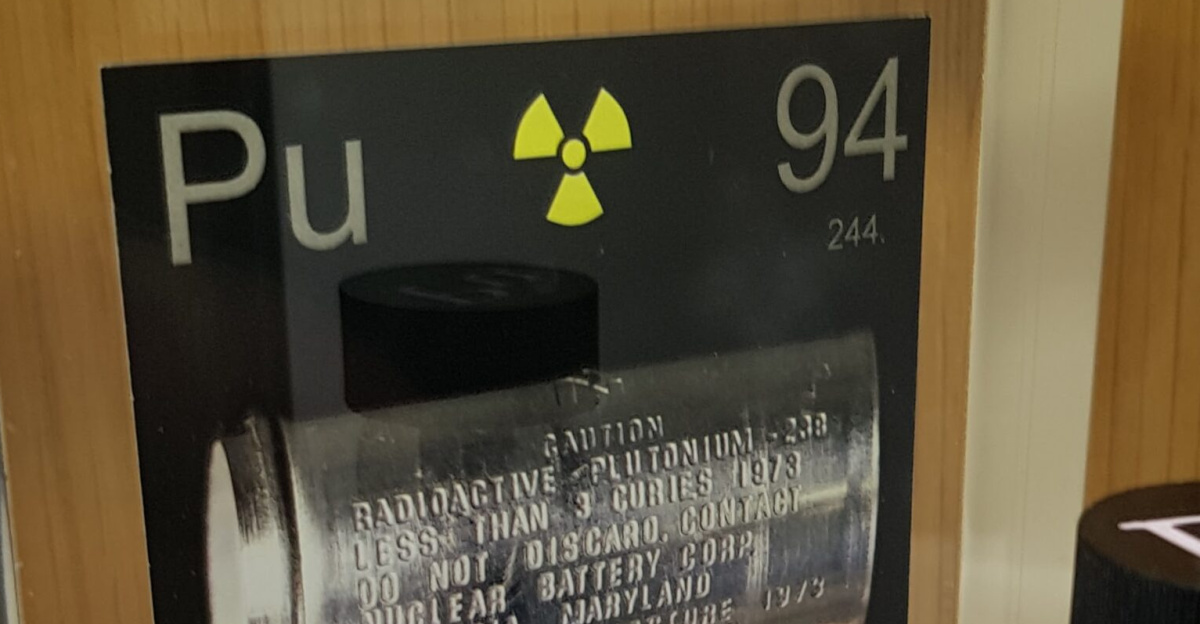

Slowly Fading Power Supply

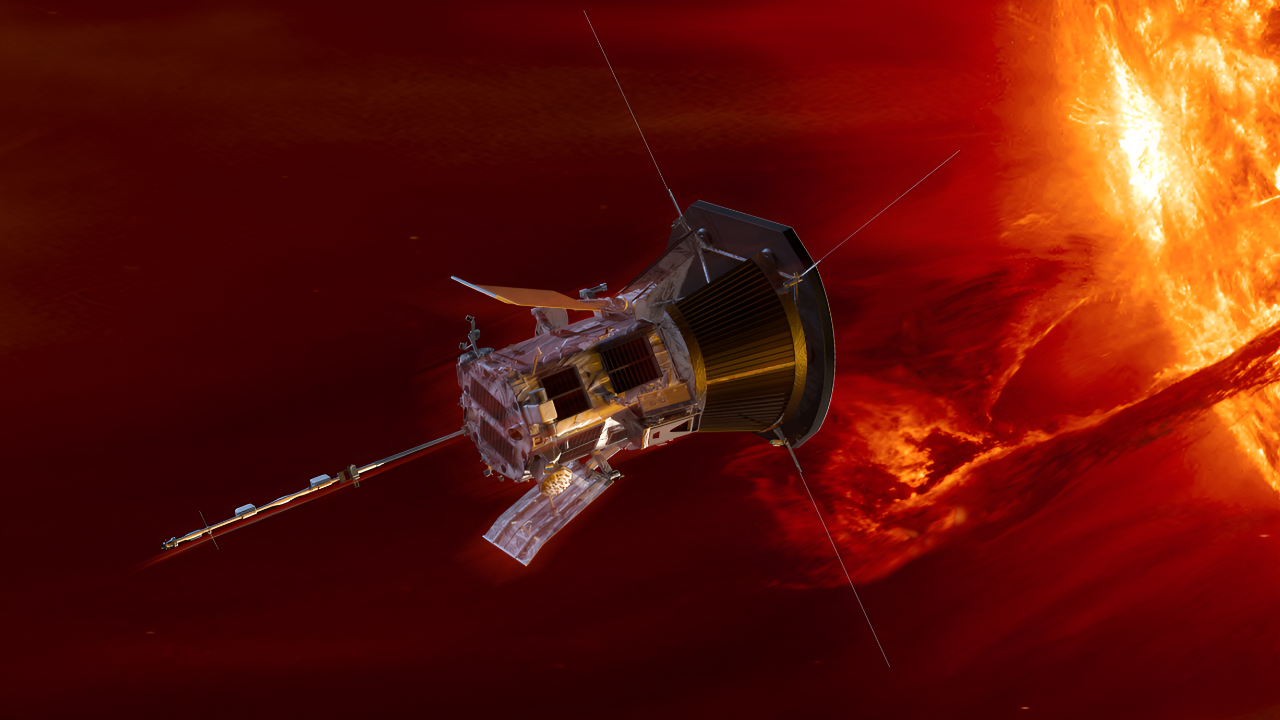

Voyager 1 doesn’t use solar panels as it’s too far from the Sun for that. Instead, it relies on radioactive plutonium that generates heat converted to electricity. This power source loses about 4 watts of energy every year. To keep the lights on, NASA has been turning off instruments one by one.

In February 2025, the cosmic ray detector shut down. More will follow. By the 2030s, the mission will likely end not with a bang but quietly, when the remaining power can no longer run the transmitter. For now, three science instruments still operate, studying the boundary between our solar system and interstellar space.

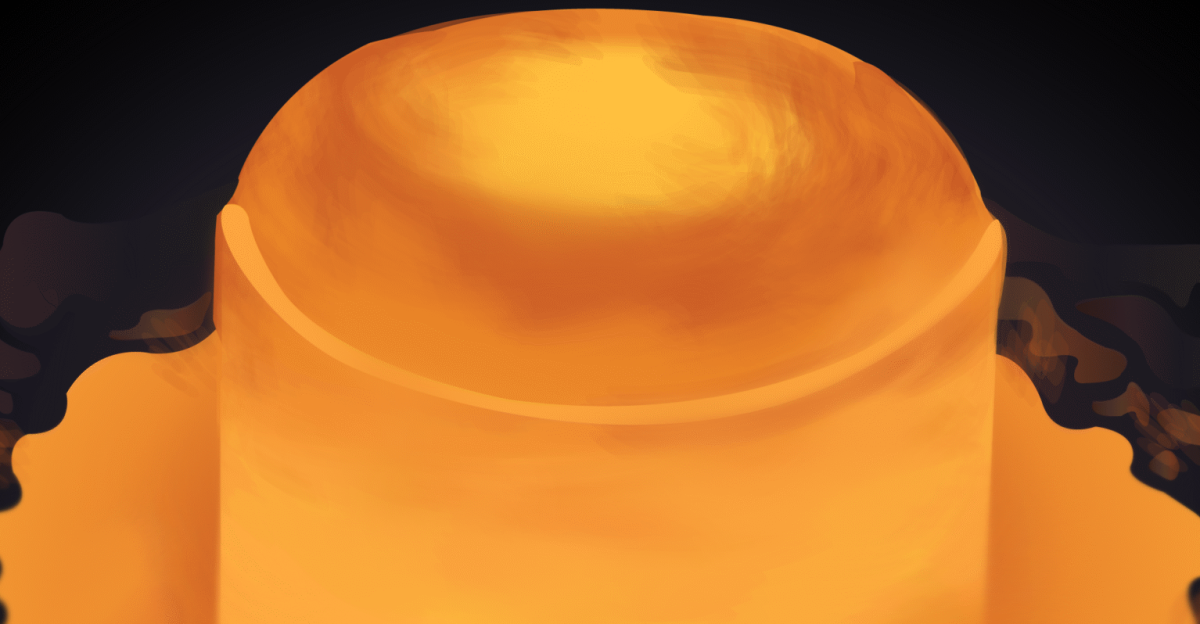

The Mysterious Wall of Fire

When Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space, its instruments recorded something shocking: temperatures suddenly jumped to 50,000 Kelvin (about 90,000°F). Scientists call this the heliopause, a wall where the Sun’s influence ends and deep space begins. Even stranger, the magnetic field in interstellar space aligned parallel to the Sun’s magnetic field, something nobody predicted.

These discoveries are reshaping how scientists understand space physics and challenging decades-old theories. The Voyagers aren’t just tourists in space; they’re explorers genuinely discovering new things about our universe.

Teaching Robots to Think for Themselves

When messages take two days to go back and forth, humans can’t control a spacecraft in real-time anymore. Voyager 1 pioneered a new model: the autonomous probe. It diagnoses its own problems, executes repairs using pre-programmed protocols, and makes decisions without waiting for permission from Earth.

This approach will define future deep-space missions to Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Titan, and beyond. Voyager proved that reaching distant places doesn’t require instant control. It requires brilliant design, reliable systems, and trust that the spacecraft can solve tomorrow’s problems without us.

Managing Missions in Slow Motion

The engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory face a unique psychological challenge. Every decision must be made with incomplete information. They send a command today, get results tomorrow, and must make the next move without knowing if the previous one succeeded.

This slow-motion mission management forces a different mindset, one emphasizing careful planning, redundant systems, and acceptance of uncertainty. These engineers are pioneers of a new kind of space exploration, teaching future teams how to explore worlds where real-time control is impossible and trust in your own design becomes essential.

1970s Tech Still Outperforming

Voyager 1’s computers have about 3 million times less memory than a modern smartphone. The communication system transmits at only 40 bits per second—slower than a dial-up modem from the 1990s. Yet this ancient technology keeps working in extreme cold, deadly radiation, and isolation that would destroy modern equipment in seconds.

This longevity reflects something often forgotten: smart engineering from the 1970s built things to last. Today’s computers are faster and smaller, but they’re also more fragile. Voyager teaches an uncomfortable lesson: sometimes durability matters more than raw speed.

When the Lights Go Out

Around the early 2030s, Voyager 1’s plutonium-powered generator will weaken beyond the point where it can run the transmitter. When that happens, the connection to Earth will end. But the spacecraft won’t stop moving.

It will continue drifting through interstellar space for millions of years, carrying a golden record with sounds and images from Earth like music, greetings in 55 languages, and a message from Carl Sagan: which reads “This is a present from a small distant world.” When the transmitter goes silent, humanity loses a voice, but Voyager’s journey continues, perhaps to be discovered by someone, or something, far in the future.

The Next Generation of Explorers

New Horizons, launched in 2006, continues traveling but remains decades behind Voyager. Experimental concepts like Breakthrough Starshot propose laser-powered spacecraft that could reach nearby stars within decades. Yet Voyager’s real achievement isn’t speed. It’s resilience. The probe succeeded through thoughtful engineering, built-in redundancy, and the willingness to operate in extreme conditions for decades.

Future missions will copy this blueprint. As we dream about Mars colonies and asteroid mining, Voyager 1 reminds us that the ultimate frontier belongs to those patient enough to travel slowly, humble enough to prepare for problems, and bold enough to explore when real-time control is impossible.

A Quiet, Enduring Promise

As Voyager 1 edges toward that one light-day milestone in late 2026, its journey reminds us that true exploration thrives on patience and ingenuity, not just speed or control. This plucky probe, born in the 1970s, has outlasted expectations by revealing the Sun’s protective bubble, challenging our cosmic models, and pioneering autonomous operations in the void, proving that human curiosity can span billions of miles without constant oversight.

In an era of rapid tech, Voyager teaches humility: some discoveries demand decades of drift, turning isolation into inspiration and ensuring our farthest reach echoes for generations

Sources:

Ecoticias – “Voyager 1 finds wall of fire at 90,000 ºF,”

Karmactive – “NASA’s Voyagers Navigate 90000°F ‘Wall of Fire’

SciTechGen – “NASA’s Voyager Spacecraft Found A ‘Wall’ At The Edge Of Our …”

Economic Times – “Voyager hits a ‘Wall of Fire’: NASA probe finds a furnace at the edge …”