A 40-year-old Hispanic man in Massachusetts now faces silicosis, an incurable lung disease. He spent 14 years cutting, polishing, and installing engineered stone countertops.

This work exposed him daily to crystalline silica dust, which can permanently scar lung tissue. On December 9, 2025, Massachusetts confirmed its first diagnosis as a case linked to the engineered-stone countertop industry.

His case signals a growing public health crisis, as similar diagnoses emerge across the United States.

The Rise of Engineered Stone

Engineered stone countertops have experienced explosive growth in popularity over the past 20 years. These products combine natural stone with resins and pigments to create a unique blend.

Homeowners love them for durability and low maintenance. Builders prefer them over granite or marble. This industry boom created thousands of fabrication jobs, mostly for Hispanic and Latino workers in their 20s, 30s, and 40s.

The rapid growth prioritized expansion over worker safety.

The Hidden Danger in the Material

Engineered stone contains over 90 percent crystalline silica. Natural granite contains less than 45 percent.

When workers cut, grind, and polish these countertops, they create fine dust. Workers inhale silica particles that lodge in their lungs. The body cannot remove these particles.

They accumulate and cause progressive scarring. Engineered stone is roughly twice as dangerous as natural stone when workers lack proper dust protection.

When Symptoms Appear

Silicosis develops slowly, with a 10- to 20-year lag between exposure and the onset of symptoms.

The Massachusetts patient worked 12 years before symptoms started. After 10 years, he developed a cough and shortness of breath. Four years later, medical tests confirmed the presence of silicosis.

This delay creates a cruel trap: workers feel fine while lung damage accumulates silently. Early detection becomes nearly impossible for most patients.

The Confirmation: Massachusetts’ First Case

On December 9, 2025, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health officially confirmed the state’s first case of silicosis linked to engineered stone work.

The patient worked for two different stone countertop companies over a 14-year period. Emily H. Sparer-Fine, who leads occupational health surveillance, stated: “This case reminds us silicosis is here and harming Massachusetts workers.”

Experts predict that this will not remain an isolated case, but rather signal many more diagnoses.

Workplace Conditions That Set the Stage

The patient’s first employer’s facility was extremely dusty. Workers did not use wet-cutting methods, the main dust control tool.

Instead of proper masks, the employer provided thin surgical masks offering minimal protection. These conditions reflect widespread safety problems in the countertop industry.

Many small workshops lack dust-control systems or proper safety training for their workers.

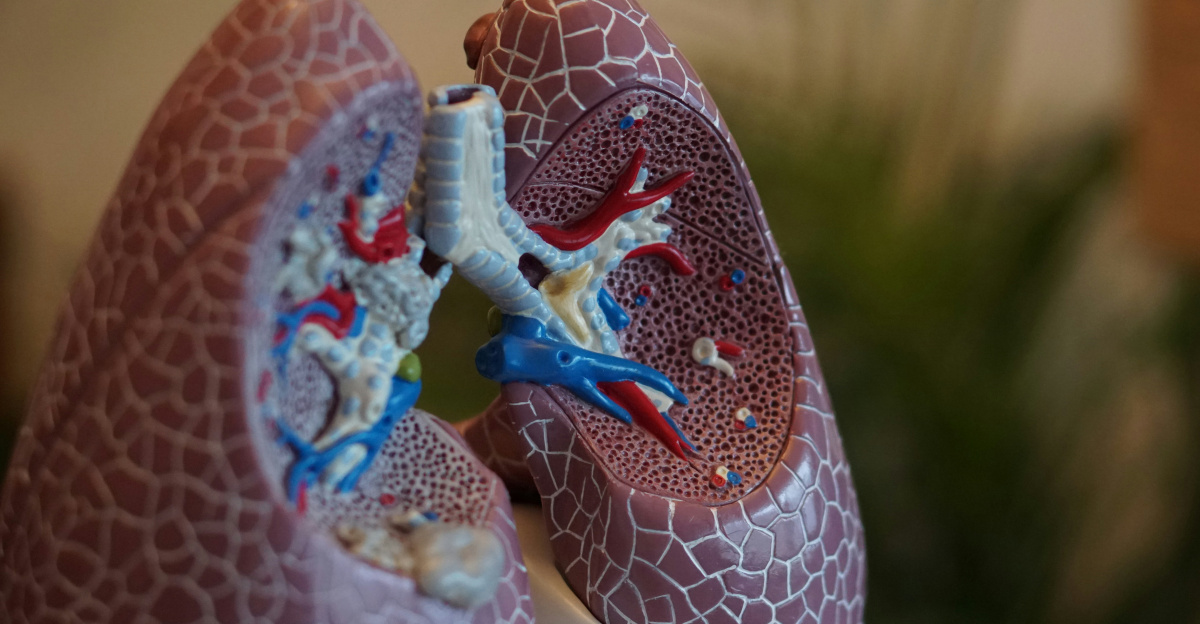

What Silicosis Does to the Body

Silicosis causes progressive lung tissue scarring. Early symptoms include a persistent cough, mucus production, and shortness of breath.

As the disease advances, patients suffer fatigue, chest pain, swollen legs, and bluish lips from oxygen loss. Silicosis increases the risk for lung cancer, tuberculosis, and high blood pressure.

In severe cases, it becomes life-threatening. Health Commissioner Dr. Robbie Goldstein said, “Silicosis is devastating and preventable.”

No Cure, Only Management

Silicosis has no cure. Once silica scars the lungs, damage cannot be reversed. Treatment focuses on managing symptoms through medication, oxygen therapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation.

Severe cases may qualify for lung transplants, with 76 percent surviving three years. However, transplants are invasive and require lifelong immunosuppression drugs. Few patients qualify.

Most adapt to progressive illness without a cure. Life expectancy ranges from 5 to 20 years after diagnosis, depending on the stage of the disease.

California’s Catastrophe: A Cautionary Tale

California shows what Massachusetts may face. As of November 2025, California reported 432 confirmed silicosis cases, at least 25 deaths, and 48 lung transplants from engineered stone exposure since 2019.

The surge is shocking: only 13 cases in 2019 rose to 432 by 2025—a 33-fold increase in six years.

This explosion reflects the booming industry and the long delay between exposure and diagnosis. Many more cases will emerge.

A Demographic Crisis: Hispanic and Latino Workers Bear the Burden

Most engineered-stone workers are male, young (with over 50 percent under the age of 45), and Hispanic or Latino (more than one-third). Silicosis cases follow this exact pattern.

This disparity reflects both workforce makeup and gaps in safety training, language access to hazard information, and workplace protections.

The disease concentrates among marginalized workers with fewer resources to demand safe conditions. This is not random—it reflects systemic inequality.

The First Case in America: Texas 2014

Silicosis among engineered-stone workers is not new; it is just invisible. The first U.S. case emerged in Texas in 2014.

A polisher, laminator, and fabricator at an engineered-stone company was exposed to quartz materials. Medical literature documented this case. For 11 years, he remained alone—the only American with engineered-stone silicosis.

Then, around 2019, cases began accelerating rapidly. A rare disease became an emerging epidemic.

Federal Standards That May Lag Behind Reality

In March 2016, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration updated silica exposure limits. OSHA lowered the maximum to 50 micrograms per cubic meter over an eight-hour period—five times lower than the old construction standards.

Rules required dust controls, including wet cutting, dust collection, ventilation, and the use of respirators. Critics argue that OSHA standards assume full compliance and overlook the realities in small shops.

Cost, language barriers, and weak enforcement undermine worker protection.

International Response: Australia’s Dramatic Ban

Australia took action that the United States avoided. In December 2023, Australia unanimously decided to ban all engineered stone countertops, panels, and slabs.

The ban took effect on July 1, 2024. It prevents manufacture, supply, processing, and installation, with narrow exceptions for removing old benchtops. Australia has cited unprecedented rises in silicosis among engineered-stone workers.

The same trend threatens the United States. Australia became the first major nation to ban engineered stone commercially.

Why Prevention Matters: The Case for Urgency

Once silicosis develops, options shrink, and outcomes worsen. Stage one patients live 20 to 27 years, stage two patients live 16 to 20 years, and stage three patients live 7 to 11 years.

Early detection through chest X-rays or CT scans extends survival by years. Most cases are diagnosed at late stages, after irreversible damage has occurred.

Prevention timing matters critically: workers need protection before exposure, not treatment after diagnosis.

The Latency Time Bomb

The 14-year gap between exposure and diagnosis reveals a hidden crisis. Thousands of fabrication workers exposed between 2005 and 2015 may silently develop silicosis without being aware of it.

With typical 10 to 20-year lags, Massachusetts and other states should expect major diagnosis waves within five to ten years.

Following California’s pattern, this surge will strain occupational health resources. Employers and regulators face pressure to act immediately.

Legislative Pressure and Emerging Proposals

State and federal legislators now propose stricter regulations. Some expand medical surveillance, mandate chest X-rays for at-risk workers, and increase penalties for safety failures.

Other bills aim to restrict or ban the sale of engineered stone in Australia. Trade groups argue that existing OSHA standards work and bans cause economic harm.

The battle intensifies between worker advocates demanding prevention and industry groups supporting current compliance.

Contractors, Architects, and Consumer Demand

The silicosis crisis reshapes the entire countertop industry. General contractors and installers face liability and safety obligations.

Architects must reconsider specifying engineered stone for projects. Consumer awareness grows: homeowners learning about risks may demand natural stone, recycled glass, or sintered stone alternatives exempt from Australia’s ban.

Demand shifts could accelerate the industry’s move away from quartz. Worker exposure drops only if consumers actively choose safer options.

Public Awareness and Misinformation

Massachusetts news sparked viral social media discussions that mixed facts with myths. False posts claim all countertops are dangerous; sealed, undisturbed stone poses minimal risk.

Real hazards occur during fabrication, cutting, and renovation when dust forms. Other posts dismiss this as isolated cases; California’s 432 cases prove otherwise.

Health officials struggle to communicate nuance: engineered stone is safe when installed, but extremely hazardous during manufacturing.

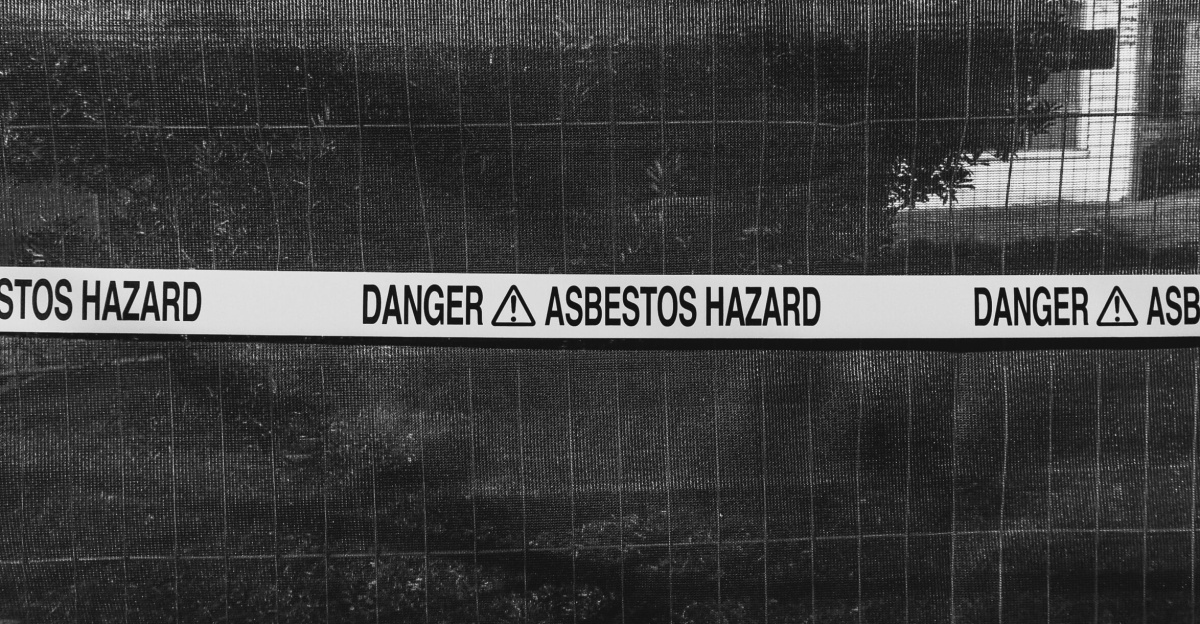

Asbestos and Silica’s Twin Threat

The engineered-stone silicosis epidemic mirrors past occupational disasters. Like asbestos in the 1900s, the dangers of silica were known but ignored in booming industries.

Workers faced decades of exposure before widespread awareness triggered lawsuits and the implementation of regulations. Crystalline silica hazards have been recognized for over 100 years, yet engineered stone dangers have gone overlooked during the industry’s growth.

Without aggressive prevention now, thousands more workers will develop silicosis. History repeats its tragic lessons.

Prevention Is the Only Cure

Massachusetts’ confirmation of silicosis in a stone countertop worker sends a clear message: a preventable occupational disease is spreading across the United States among workers lacking hazard awareness and protective equipment.

Silicosis offers no cure, no lung repair, and limited treatment beyond symptom management. Prevention remains the only effective answer: implementing strict dust controls, using proper respirators, ensuring adequate workplace ventilation, conducting regular medical monitoring, and maintaining honest and open hazard communication.

The next two to three years determine whether this case becomes a heeded warning or the first domino in an expanding epidemic.

Sources:

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Massachusetts Public Health Officials Issue Safety Alert to Employers After State’s First Confirmed Silicosis Case in Stone Countertop Industry, December 9, 2025

Fox News, Massachusetts man diagnosed with deadly lung disease linked to popular kitchen countertops, December 11, 2025

The Independent, Dust from popular countertop material that causes incurable lung disease linked to death of Massachusetts worker, December 11, 2025

Brayton Law, Massachusetts Issues Safety Alert After First Silicosis Case in Artificial Stone Countertop Industry, December 12, 2025

PubMed/NIH, Notes from the field: silicosis in a countertop fabricator, February 2015

SafeWork Australia, Engineered stone ban, December 2023