In the summer of 2024, archaeologists made a groundbreaking discovery that had eluded researchers for over 400 years.

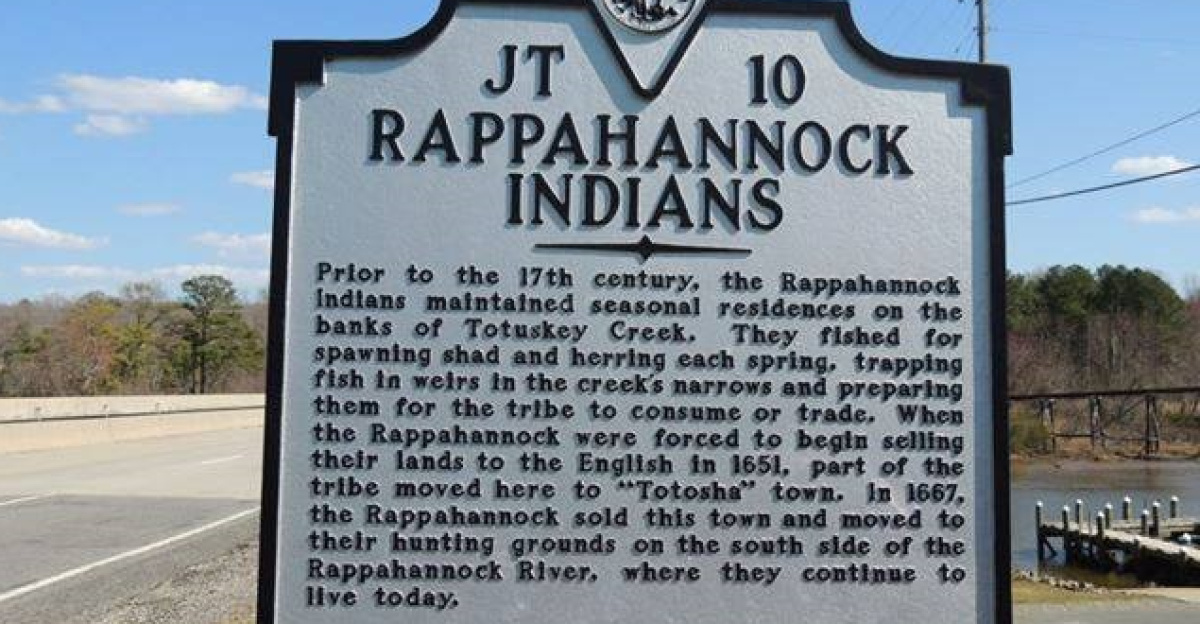

Captain John Smith’s 1608 map had marked the locations of three Native American villages along Virginia’s Fones Cliffs, but for centuries, no physical evidence was found.

That changed when excavations uncovered around 11,000 artifacts, from pottery shards to stone tools, solidifying what oral histories had always claimed. These villages were real, thriving, and located exactly where the Rappahannock Tribe had said they were.

The Stakes Mount

The discovery arrives as the Rappahannock Tribe nears completion of reclaiming 2,100 acres of ancestral land—an achievement laden with symbolic weight.

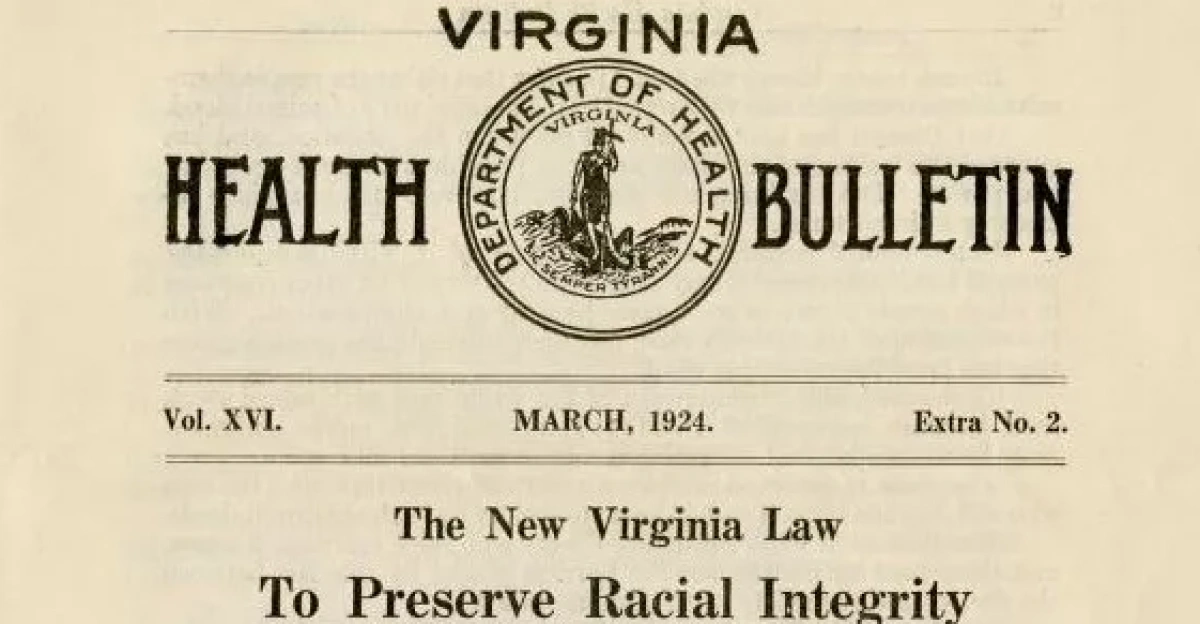

Once controlling over 350,000 acres across Virginia’s Northern Neck during their mid-to-late 1500s peak, the tribe was systematically stripped of territory through colonial seizure in the 1640s, lopsided treaties (such as 30 blankets for 25,000 acres in the 1660s), and legal erasure (the 1924 Virginia Racial Integrity Act).

Today’s land restoration, though modest in acreage, signals a turning point after 300 years of displacement and legal invisibility.

Colonial Cartography and Doubt

Captain John Smith’s 1608 voyage and 1612 map became foundational documents of early American history. Yet his descriptions of three Rappahannock towns—Wecuppom, Matchopick, and Pissacoack—clustered at Fones Cliffs faced skepticism for centuries.

Historians debated whether Smith exaggerated indigenous settlements or conflated different sites. Without archaeological confirmation, scholars could neither prove nor disprove his claims.

The Rappahannock Tribe maintained unbroken oral traditions that pinpointed the locations, but mainstream science required physical evidence for validation.

A Tribe Erased, Then Remembered

Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act forced every resident into a White/Black binary, legally erasing Native American identity statewide.

The Rappahannock Tribe, with roughly 2,400 members at its historical peak, had shrunk to approximately 300 individuals by the 21st century, having been denied tribal status and land rights for generations.

Despite this institutional erasure, the tribe continued to hold ceremonies, fish, and preserve ancestral knowledge on privately owned land that they didn’t control.

Federal recognition finally arrived in 2017—a watershed moment enabling formal land reclamation efforts and archaeological partnerships.

The Archaeological Breakthrough

Excavations began in the fall of 2023, but the transformative discovery was made in summer 2024. St. Mary’s College of Maryland archaeologists, working alongside the Rappahannock Tribe and conservation partners, unearthed approximately 11,000 artifacts across multiple Fones Cliffs sites.

Beads, pottery shards with intricate markings, stone tools, and pipes emerged from the Virginia soil, with some pieces dating to the 1500s—well before English contact.

Blackened dirt and rock formations suggested hearths where families once cooked and gathered. This physical evidence finally validated Smith’s 1608 map with undeniable archaeological proof.

The Indian Peter Story

One parcel at Fones Cliffs bears particular historical resonance: the “Indian Peter” site, named after an 18th-century man born to an English father and Rappahannock mother. Historic documents promised him freedom, though the term’s meaning remains contested.

Archaeologists recovered approximately 2,500 artifacts at this location alone, offering a micro-archive of early colonial-era indigenous life during the transition period.

The site’s concentrated findings suggest a focal point of habitation or community activity, enriching our understanding of how Rappahannock families adapted through centuries of upheaval and cultural pressure.

Chief Anne Richardson’s Validation

Chief Anne Richardson of the Rappahannock Tribe articulated the discovery’s more profound meaning: “Indian people have long known of the land and our history and presence here. But so often things aren’t considered ‘real’ until they’re found or ‘discovered.’ This validates what we’ve long known.”

Richardson, the fourth-generation chief of her family’s leadership lineage, has spearheaded the tribe’s century-long fight for land restitution and federal recognition.

Her words encapsulate the colonial epistemology challenge—that Western science demands material proof before honoring indigenous knowledge, which has been preserved orally for millennia.

Competing Archaeological Visions

The Fones Cliffs discovery reflects a broader shift in American archaeology: integrating tribal knowledge with academic methodology. Previously, archaeologists conducted digs independently, often without consulting descendants of the people they studied.

This excavation reversed that power dynamic—oral histories and tribal guidance pointed researchers to precise dig sites. The Conservation Fund and St. Mary’s College prioritized collaborative frameworks, recognizing that Rappahannock elders’ accumulated geographic and cultural knowledge surpassed conventional survey techniques.

This model increasingly influences how universities and nonprofits approach indigenous heritage sites nationwide.

The Broader Land-Back Movement

The Rappahannock reclamation is part of a national resurgence in tribal land restoration. From California to Maine, Native American nations are acquiring ancestral territories through purchase, conservation easements, and legislative agreements.

The Crow Nation in Montana, the Yurok Tribe in California, and dozens of others have finalized “land-back” deals totaling hundreds of thousands of acres over the past decade.

Federal recognition improvements and philanthropic funding have accelerated these efforts, though they remain fractional recoveries of what colonialism seized. Virginia’s Rappahannock case exemplifies this movement’s logic and limits.

The 99.4% Reality Check

While the Rappahannock Tribe celebrates reclaiming 2,100 acres, the starkness of colonial dispossession is revealed through the numbers. At their mid-to-late 1500s peak, the tribe controlled 350,000+ acres along Virginia’s river valleys.

Today’s reclaimed acreage represents 0.6% of that historical territory—a recovery rate underscoring generational wealth theft and structural inequity.

This gap illustrates why land-back movements remain symbolic victories despite their profound personal and cultural significance. The tribe is rebuilding presence and sovereignty, yet the quantitative loss of ancestral territory persists across centuries despite recent progress.

Who Owns the Narrative?

The discovery also surfaces unresolved tensions between tribal authority, archaeological institutions, and government agencies. St. Mary’s College and the Conservation Fund hold partnerships and grant funding, creating incentives for academic publication and external legitimacy.

Yet the Rappahannock Tribe holds primary claim to the findings and their interpretation. Questions linger: Who controls future archaeological access? How are artifacts cataloged and stored? Do tribal members have veto power over research directions?

These dynamics reflect broader power imbalances in heritage management, where indigenous sovereignty and academic authority historically conflict.

Leadership and Reclamation Strategy

The tribe’s land acquisition strategy combines direct purchase, conservation easements with nonprofits, and partnerships with federal agencies. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service owns one Fones Cliffs parcel; the Rappahannock Tribe has secured two adjacent parcels through conservation agreements.

This patchwork approach reflects pragmatic coalition-building rather than unified tribal ownership—a compromise many tribes accept to accelerate land return.

Chief Richardson and the tribal council have prioritized accessibility and education over exclusive control, planning a welcome center, interpretive trails, and educational kiosks for public visitation and learning.

Infrastructure Dreams: Welcome Center Plans

The Rappahannock Tribe envisions transforming Fones Cliffs into an educational anchor for regional history. Plans include a welcome center, walking trails that navigate archaeological sites, and educational kiosks that explain artifact finds and Rappahannock culture.

The infrastructure would serve dual purposes: generating economic benefit for the tribe through tourism and reclaiming control over how their history is told.

Schools could organize field trips, allowing visitors to encounter indigenous narratives firsthand rather than through colonial filters. This represents a strategic shift from passive recovery to active historical curation.

Archaeological Skepticism and Questions

Not all experts view the discovery unambiguously. Some archaeologists caution against over-interpreting artifact clusters as definitive settlements—beads and tools could indicate seasonal camps, trade sites, or ritual locations rather than permanent villages.

Others question whether Smith’s 1608 map was precise enough to warrant such confident correlation. Scholars also note that 11,000 artifacts across multiple years of excavation represent a significant but not unprecedented find for a four-century-old site.

These reservations don’t invalidate the discovery but remind us that archaeological interpretation remains contested and evolving, especially regarding indigenous histories.

What Comes Next for Rappahannock History?

Future excavations are likely to expand beyond Fones Cliffs into adjacent areas, where Smith’s map suggests additional settlements. The tribe has identified multiple other parcels of interest, though acquiring and surveying them requires sustained funding and institutional support.

DNA analysis of remains, pollen cores that reveal subsistence practices, and comparative artifact studies could deepen our understanding of pre-contact Rappahannock life.

Yet the fundamental question lingers: How many more villages await discovery, and will adequate resources and tribal consent support their systematic, collaborative investigation?

Political Implications and State Recognition

Virginia’s historical erasure of Native Americans through the 1924 Racial Integrity Act represented one of America’s most explicit state-level denials of indigenous existence. The Rappahannock discovery and land reclamation now compel Virginia policymakers to reckon with that legacy.

Conversations are emerging about formal apologies, curriculum reforms, and expanded state recognition of tribal sovereignty. Other Virginia tribes, such as the Pamunkey and Mattaponi, similarly navigate post-federal recognition land claims and historical visibility.

The Rappahannock case sets a precedent for how states address cumulative historical wrongs through archaeology and policy reform.

National and Global Precedents

The Rappahannock discovery resonates internationally among indigenous populations reclaiming heritage and land. Indigenous communities in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and throughout the Pacific face parallel archaeological questions: Who controls narratives about pre-contact settlements? How do oral traditions integrate with academic rigor?

The Rappahannock case exemplifies successful collaboration between tribal authority, Western institutions, and governments—a model both praised and critiqued as colonialism-lite by some indigenous scholars who argue true decolonization requires indigenous-led research independence without Western partnership requirements.

Environmental and Ecological Dimensions

Fones Cliffs represents a geologically and ecologically unique landscape. The white diatomaceous earth forming the cliffs originated five million years ago when shallow seas covered the region, creating fossilized aquatic organisms.

Today, the wetlands support a diverse array of wildlife, including bald eagles, various fish species, and rare habitat types. The Rappahannock Tribe’s stewardship plans emphasize conservation alongside cultural reclamation—protecting ecological integrity as an ancestral responsibility.

This environmental dimension distinguishes the tribe’s land-back vision from purely extractive development models, positioning indigenous governance as compatible with ecological restoration and long-term sustainability.

Generational Trauma and Cultural Resilience

For approximately 300 years (1640s through 2017), Rappahannock children grew up without a formal tribal homeland or official recognition. Ceremonies occurred on borrowed private land. Federal erasure severed legal identity, though the tribe’s internal cultural transmission persisted.

Today’s youth witness land return, archaeological validation, and institutional recognition—a reversal reshaping tribal consciousness. Psychologists and indigenous scholars note the profound psychological impact of land reclamation on generational trauma healing.

The welcome center and trails project becomes not just infrastructure but a therapeutic space where descendants encounter ancestral presence materially and spiritually.

The Larger Reckoning

The Rappahannock discovery ultimately signals something broader than archaeological confirmation: the limits and possibilities of American reckoning with the dispossession of indigenous peoples.

Archaeological evidence validates what the tribe always knew, yet the need for Western scientific proof itself reflects colonial epistemology. Land returned, measured in thousands of acres, against the historical dispossession of millions, represents progress and perpetual incompleteness.

As the Rappahannock Tribe builds its welcome center and interprets its past, the larger question emerges: Will America fundamentally restructure its relationship with indigenous nations, or will land-back remain a corrective gesture within an inherently unjust colonial framework?

Sources:

Washington Post, November 27, 2024

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2025

CNN, April 2, 2022

The Valentine (Richmond), May 23, 2024

Encyclopedia Virginia, August 25, 2024

Archaeology Magazine, November 2024 / January-February 2021

Rappahannock Tribe Annual Report, February 2024

St. Mary’s College of Maryland Archaeological Records