Brown floodwater churned through downtown streets as headlights reflected off the rising surface, drivers inching forward while rain hammered windshields in steady sheets. On neighborhood hillsides, water spilled over curbs and raced downhill, carrying branches toward clogged grates already drowning under runoff. It was still early in the storm, and forecasters warned that more intense bursts were coming.

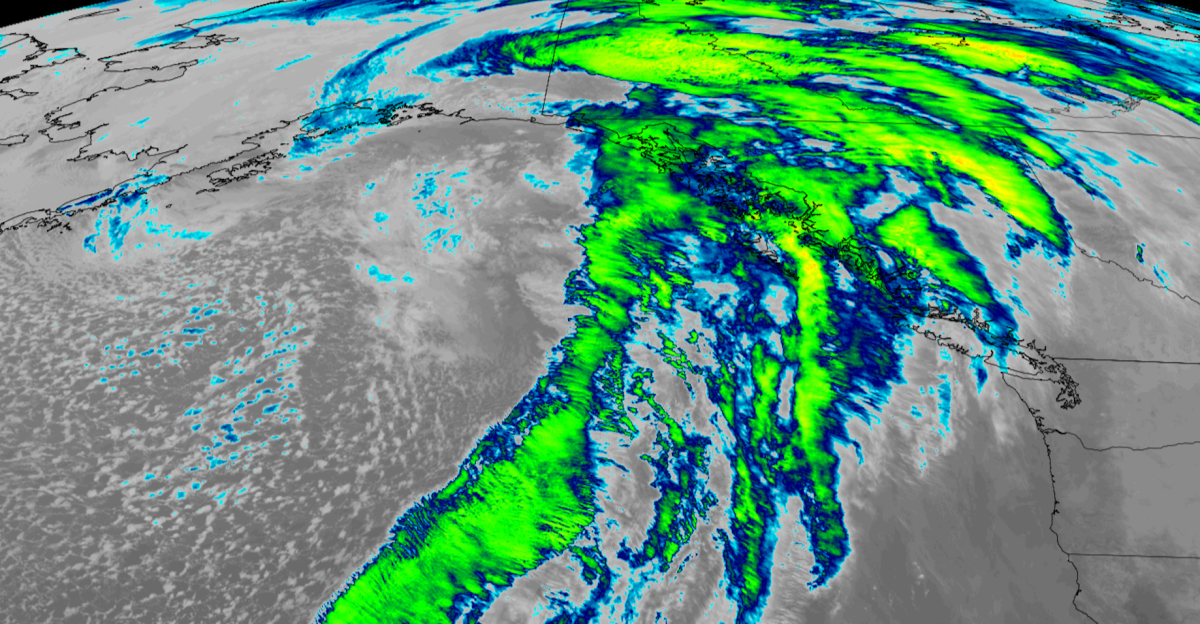

Meteorologists say this week may deliver the wettest three-day stretch of the 2025–26 season, fueled by a Level 4 of 5 atmospheric river capable of dumping up to 18 inches of rain into the Pacific Northwest’s already saturated terrain.

Stakes Rising

Forecasters describe the system as “mostly hazardous,” the designation assigned when atmospheric rivers deliver substantial water supply benefits but also heightened flood impacts. With soils saturated from earlier storms, rivers and urban drainage systems will respond faster to new rainfall, increasing the likelihood of widespread runoff.

The Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes classified this system as Level 4 of 5, a category associated with significant flood risk. Level 4 events remain uncommon but drive some of the costliest winter storms on the West Coast.

Rivers In The Sky

Atmospheric rivers function like long aerial conveyor belts, channeling water vapor from the subtropics into regions like Washington and Oregon. When that moisture slams into mountain ranges, air is forced upward, condensing into heavy rainfall that wrings every drop from the saturated plume.

Scientists emphasize that strong atmospheric rivers often carry more water than the world’s largest terrestrial rivers, explaining why a single event can cause both life-saving water supply gains and destructive flood surges.

Weeklong Barrage

This is the third atmospheric river in a cluster of three, a rare sequence even for the Pacific Northwest’s rainy season. Each event laid a foundation of soil saturation, meaning the final and strongest system will turn more rainfall into immediate runoff rather than absorption.

Meteorologists say the cumulative effect is what makes this week unique. Rivers that started at seasonal highs may cross into minor and moderate flood stages once this final burst hits.

18 Inches Incoming

Forecasts center on the rainfall totals. Parts of the Cascade Mountains may receive up to 18 inches, while coastal zones take 5–10 inches, fueling rapid rises in creeks and rivers. In lower elevations, widespread 3–6 inch totals are expected by week’s end, exceeding seasonal norms.

Snow levels between 7,000 and 9,000 feet mean precipitation falls overwhelmingly as rain. That keeps water moving downhill rapidly, denying ski areas valuable early-season snowpack.

Two States Drenched

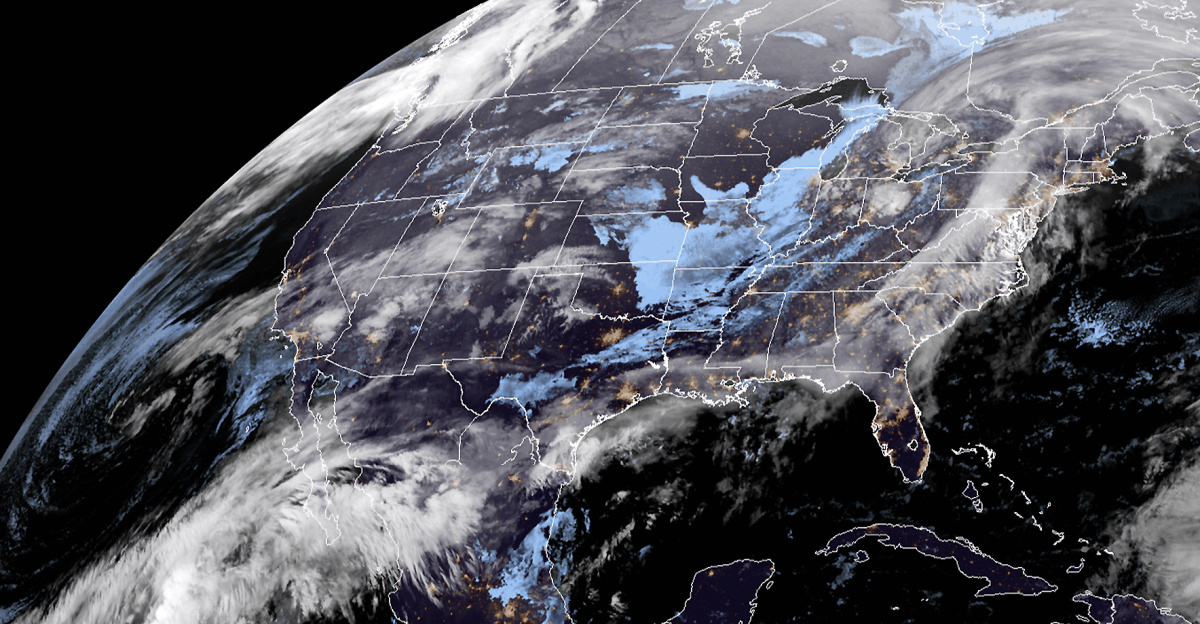

Washington and Oregon sit directly beneath the moisture plume, triggering flood watches across both states. Major metros including Seattle, Portland, and Salem face urban flooding hazards where drainage systems are easily overwhelmed.

Coastal and foothill communities, positioned closer to the moisture-rich plume, will take the brunt of the rainfall. Forecasters warn that flashier streams and creeks may flood first, often hours before larger rivers reach crest.

Flood Lines Forming

Hydrologists expect multiple river gauges in western Washington, including the Snoqualmie near Carnation, Skykomish near Gold Bar, Snohomish near Snohomish, and Skagit near Concrete, to exceed minor flood stage, with several reaching moderate levels. That means water in low-lying farm fields, across rural roads, and in some residential neighborhoods where riverbanks have limited capacity.

The system’s integrated vapor transport index surpasses 1,000 kg m⁻¹ s⁻¹, placing it within the range of extreme atmospheric rivers historically linked to high-impact flooding on the West Coast.

Millions On Alert

Flood watches affect millions of residents across western Washington and Oregon. Weather officials cite a fast-rising threat window: multiple days of heavy rain, peak intensities near 1 inch per hour, and fast-moving runoff.

Communities in river valleys and flood-prone areas face elevated water levels and potential inundation. Officials say property exposure, not just rainfall totals, drives risk.

Dollars On The Line

Damage estimates span $50 million to $150 million, depending on river crest heights and how deeply neighborhoods flood. Economic impact models factor in home values, infrastructure, insurance coverage, and recovery timelines.

For context, atmospheric river storms account for nearly 90 percent of flood-related damage in the Western U.S., totaling over $1 billion annually. Even moderate flooding in urban regions can accelerate costs rapidly.

Hidden Costs Add Up

Warm, early-season storms threaten more than homes. With snow levels rising to 7,000–9,000 feet, rain falling on ski slopes erodes snowpack and closes terrain. Early season storms can significantly reduce ski industry revenue for the season.

Winds above 40 mph, combined with unstable trees in saturated soil, could create widespread power outages, stressing local businesses and households.

Drought Whiplash

The Pacific Northwest entered this week with drought conditions across multiple basins, a paradox in a region famous for rainfall. Atmospheric rivers supply 30–50% of annual precipitation, meaning extreme events can be both critical and hazardous.

Drought makes flooding worse, not better. Hardened soil repels water, pushing rainfall into rivers and storm drains faster than they can manage.

Land At Risk

Steep, erosion-prone terrain across the Coast Range and Cascades may receive more than 10 inches of rain, increasing landslide potential. Debris flows often strike roads, smaller bridges, and transmission lines.

Hazards extend beyond mapped floodplains, meaning communities outside traditional risk zones may still experience transportation shutdowns and infrastructure damage.

Communities Strained

Local officials warn that residents in vulnerable areas should prepare for rapid evacuation orders, temporary sheltering, and multi-day disruptions. Past atmospheric river events have caused over 80% of regional flood losses in some studies.

For emergency managers, this storm represents the first major flood threat of the 2025–26 winter, not just a routine December rainstorm.

Managing The Risk

Modern flood prediction blends real-time rainfall, river gauge readings, and computer modeling to estimate crest heights. Risk calculators then pair flood depths with property values to forecast economic losses.

These methods support the current $50–150 million damage range, informing decisions about sandbag distribution, shelter locations, and road closures.

Peak Intensity Ahead

Forecast models show a peak rainfall period between December 8–12, with the heaviest precipitation and strongest river response toward the end of the week. Rainfall rates up to 1 inch per hour could produce flash flooding.

The Weather Prediction Center issued Level 2 of 4 excessive rainfall risk for several days, highlighting concerns for widespread runoff and river response.

Urban Exposure

Seattle, Portland, and surrounding suburbs have large populations living near rivers and creeks that respond quickly during storms. Floodwater in cities often spreads across roadways, underpasses, and commercial zones, creating large economic impacts without catastrophic river overflow.

Urban flooding, driven by drainage system overload, is expected before major rivers crest later in the week.

Transportation Trouble

Heavy rainfall and rising creeks may shut down major roadways, especially in foothill corridors leading into the Cascades. Landslides and debris flows often hit secondary roads, isolating smaller communities.

Freight and travel disruptions can ripple outward, slowing deliveries and raising costs temporarily. The Pacific Northwest’s rugged topography makes rerouting difficult.

Snow Season On Hold

Ski resorts rely on early-season snowfall to build momentum heading into winter breaks. Warm storms have delivered rain to nearly all ski terrain, erasing snowpack in days.

With 7,000–9,000 foot snow levels, the storm affects a multi-billion-dollar recreation economy. Warm precipitation during early season can significantly impact resort operations and revenues.

Bigger Storms Coming

Climate research shows warming air holds more water vapor, increasing the odds that future atmospheric rivers will become wetter, longer, and more clustered. That raises long-term questions about whether West Coast communities can withstand repeated Level 4 events with multi-million-dollar damage potential.

Without adaptation, repeated flood disasters could outpace current infrastructure capacity.

What Comes Next

As floodwaters rise, emergency agencies will monitor crest heights, landslide reports, and infrastructure failures, issuing alerts as conditions develop. Residents across western Washington and Oregon are urged to track official warnings closely.

Meteorologists emphasize that this week’s event may be a preview of a more extreme wet season, marked by volatile cycles of drought, heat, and atmospheric rivers. Communities now face the challenge of preparing for both too little water—and too much.

Sources:

Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) – AR Update (December 3, 2025)

CW3E – Quick Look Update (December 5, 2025)

National Weather Service – Weather Prediction Center (WPC) Excessive Rainfall Outlook

USGS Water Resources Data Portal

The Conversation – “Atmospheric River Storms Can Drive Costly Flooding” (2020)

Prevention Web – “Wet Soils Increase Flooding During Atmospheric River Storms”