For more than nine hours on Tuesday, Kīlauea’s summit lit up the night with molten fury. Lava fountains shot 500 to 600 feet into the darkness—one of the most spectacular displays of the volcano’s ongoing 10-month rampage. The 37th eruptive episode burst to life around 2:30 p.m. HST on November 25, turning the summit into a natural furnace.

The volcano had been quietly building pressure for days, with the north vent glowing and spitting lava into the air, signaling what scientists knew was coming.

One of Earth’s Angriest Mountains

Kīlauea holds the title as one of the world’s most active volcanoes, and the past 10 months have cemented its legend. Since December 23, 2024, the mountain has erupted 37 times—roughly one eruption every 9 days on average. Each episode has brought its own intensity: some lasted mere hours, others stretched across days.

The USGS noted that, within the past month and a half alone, recent episodes have broken records for this particular eruption cycle.

Pressure Building in the Darkness

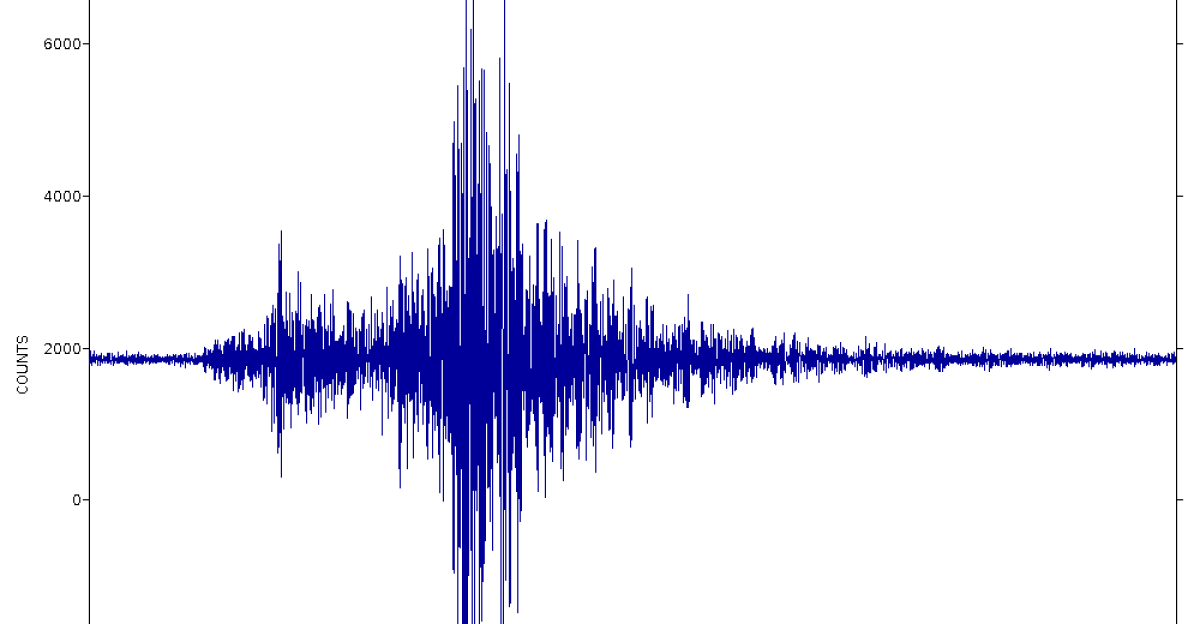

In the hours leading up to the eruption, seismic instruments detected the telltale signs. Tiny earthquakes rattled beneath the summit as magma surged upward through the volcano’s plumbing system. The USGS tiltmeter network showed ground deformation accelerating—the mountain was literally bulging as molten rock filled the subsurface reservoir.

Scientists at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory watched the readings climb on their monitors, knowing that an eruption was imminent.

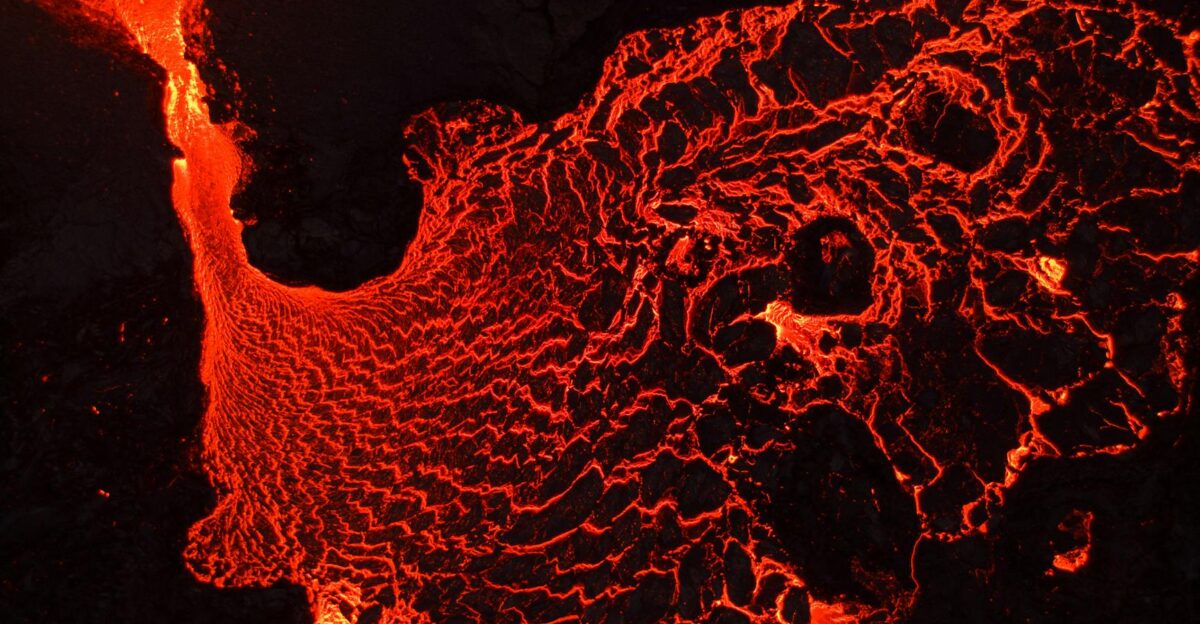

Molten Rock Paints the Sky

As darkness fell over the Big Island, the eruption intensified. The lava fountains glowed white-hot at their base, transitioning to brilliant orange and red as they arced through the cool night air. The wide fountain sent lava flows across a broad portion of the crater floor. Volcanic gases—primarily sulfur dioxide—created an eerie glow across the summit region.

Some fountains reached heights comparable to a 60-story office building, ejecting incandescent lava bombs into the sky.

7.8 Million Cubic Yards of Lava in Nine Hours

By the time 11:39 p.m. arrived, the north vent had expelled an estimated 7.8 million cubic yards of lava (approximately 6 million cubic meters). To put that in perspective, that volume would fill roughly 3,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The lava had been distributed across the summit caldera, filling low spots and reshaping the volcanic landscape in real time. Each of the 37 eruptions in this cycle has contributed to rebuilding the summit’s topography.

When the Eruption Suddenly Went Silent

At 11:39 p.m. HST on Tuesday, the north vent fell quiet. The fountains that had been painting the sky in brilliant reds and oranges stopped. The show was over—or so it seemed. The silence that followed was almost as dramatic as the eruption itself.

Observers watching from the park suddenly found themselves standing in relative darkness. The glow faded. The rumbling ceased. The mountain seemed to exhale after holding its breath for nine hours.

The Volcano Takes a Brief Breath

In the moments after the eruption ended, the mountain began deflating. Ground deformation instruments detected about 16.5 microradians of deflationary tilt—a measurable subsidence of the summit as pressure released.

The magma that had surged upward was now gone from the upper chamber, replaced by air and cooling rock. This deflation phase is a predictable part of Kīlauea’s cycle.

Ten Minutes Later, a Different Kind of Violence

The ground had other plans. Exactly 10 minutes after the eruption ended—at 11:49 p.m. local time—a magnitude 4.6 earthquake struck the southern flank of Kīlauea, centered near Puʻuʻōʻō in the Puna district.

According to the USGS, the tremor was centered on the volcano’s southern side, a region known for experiencing more frequent movement than the summit itself. The shaking was immediate, powerful, and felt far beyond the volcanically active zone.

From Big Island Bedrooms to Honolulu Hotels

The 226-mile reach of Tuesday night’s quake underscored just how potent the tremor was. Residents on Hawaiʻi’s Big Island, closest to the epicenter, felt the strongest shaking—items tumbled off shelves, bedside lamps rattled, and the kind of adrenaline spike that comes from being jolted awake in the dark. But the earthquake didn’t stop at the Big Island.

The USGS confirmed that shaking was felt as far away as Honolulu, over 220 miles northwest of the epicenter. The earthquake had announced itself across the entire state.

No Catastrophic Damage, But the Message Was Clear

When morning came, damage reports were surprisingly sparse. No major destruction was reported; the quake had been powerful enough to be widely felt but not violent enough to topple buildings or spark widespread emergency responses.

The USGS noted that little to no damage was expected. Still, the timing raised a question: What had just happened between these two extraordinary geological events?

Coincidence or Connection?

Scientists immediately began analyzing whether the sudden cessation of the eruption directly triggered the earthquake. According to the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, the magnitude 4.6 quake did not appear to be directly related to the lava fountaining itself.

Instead, most earthquakes in this region are caused by the movement of Kīlauea’s southern flank—a massive section of the volcano’s slope that shifts and adjusts in response to internal pressure changes.

Why the South Flank Moves When the Summit Erupts

Kīlauea’s architecture is complex. The summit, where the 37 recent episodes have occurred, is one system. The southern flank—the massive sloping side of the volcano facing the ocean—is another.

As magma rises and fills the summit chamber, pressure increases throughout the mountain’s structure. When that magma is suddenly expelled in a fountaining episode, the pressure on the system changes.

The Mechanics of a Sliding Mountain

Beneath Kīlauea lies a geological reality that few island residents think about: the southern flank is essentially sliding toward the ocean. Gravity, combined with internal pressure from the magma system, creates a constant force that pushes the massive section of the volcano seaward.

According to USGS monitoring data, the south flank moves at approximately 2 inches per year. Earthquakes on the south flank result from this creeping motion and stress built up along fault lines.

Repressurization Has Already Begun

By Wednesday morning, the volcano showed another telltale sign that it was gearing up again. The USGS reported that ground deformation had switched from deflation to inflation. About 6.5 microradians of inflationary tilt had been recorded since Tuesday’s eruption ended—the magma chamber was repressurizing.

This is the predictable rhythm Kīlauea has followed for the past 10 months: erupt, deflate, refill, erupt again. Scientists suggested that another eruptive episode was likely possible within weeks.

The Record-Breaking Run

What makes this current eruption cycle so remarkable is not just the frequency but the magnitude of each event. In recent episodes, some fountains have reached 1,200 feet or more—double the height of Tuesday’s display.

The USGS emphasized that past episodes have produced incandescent lava fountains exceeding 1,000 feet in height, which generate eruptive plumes extending up to 20,000 feet above ground level.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Despite the volcanic intensity, the national park has remained accessible to visitors—a testament to the predictability and containment of current activity. All eruptions have been confined to the summit’s caldera. Lava fountains, while dramatic and sometimes reaching toward the clouds, have not produced flows threatening residential neighborhoods.

The park features public viewing areas on the caldera rim, offering visitors a front-row seat to one of Earth’s most active volcanic systems.

The Scientists’ Steady Vigil

The U.S. Geological Survey maintains a constant presence at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, monitoring Kīlauea around the clock with an array of instruments—tiltmeters measuring ground deformation, seismographs recording tremors, webcams capturing the glow of vents, and gas sensors tracking emissions.

The volcano alert level remains at “WATCH,” and the aviation color code is “ORANGE,” indicating heightened unrest. This is the highest state of readiness short of an imminent eruption warning.

What Comes Next for Hawaii’s Restless Mountain

Tuesday night’s sequence—a dramatic eruption followed 10 minutes later by a widely felt earthquake—is likely just another chapter in what promises to be a long story. The inflation already underway suggests the mountain is preparing for its next episode. When it arrives, the fountains will likely soar again, residents will feel the ground shake, and the cycle will continue.

For those living on the Big Island and across Hawaiʻi, Kīlauea remains what it has always been: a powerful reminder.

Living with Volcanic Reality

The convergence of eruption and earthquake demonstrates the dynamic geological forces at work beneath the Hawaiian Islands. Thousands of residents have adapted to life in this volatile landscape, understanding that major seismic and volcanic events are not aberrations but routine features of existence here.

The events of November 25 reinforced lessons learned over generations: respect the volcano’s power, heed scientific warnings, and maintain preparedness for the next dramatic chapter in Kīlauea’s ongoing story.

A Volcano’s Relentless Rhythm

If history is any guide, the volcano is not done yet. The next eruption is almost certainly already in the works, building pressure in the darkness beneath the mountain. Scientists monitoring the inflationary tilt and deformation patterns suggest another episode could arrive at least a week away.

What is certain is that Kīlauea will erupt again, likely soon, continuing the remarkable 10-month cycle. The mountain’s restless rhythm continues, indifferent to human time scales, a testament to the dynamic forces shaping our planet.

SOURCES:

- U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (USGS HVO)

- USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory official notices

- National Park Service Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park

- USGS Volcano Watch program

- HVERI volcano monitoring data