Mars 3 became the 1st spacecraft to soft-land on Mars, touching down in Ptolemaeus Crater on December 2, 1971. Soviet engineers at Lavochkin Design Bureau guided its 1,210-kg lander down using parachutes, retro-rockets, and automated controls after years of failed attempts since 1960. The achievement should have rewritten space history, yet it faded almost instantly. However, the lander’s first moments hinted trouble overhead.

The People Who Built The Breakthrough

Mars 3 was built at Lavochkin Design Bureau under Chief Designer Georgy Babakin, whose rigorous approach reshaped Soviet planetary missions, yet he died months before launch. Key contributors included V.G. Perminov and rover designer Alexander Kemurdzhian, who developed a ski-equipped surface vehicle far ahead of its time. Some engineers were fresh from graduate school, encouraged to take big risks. Their bold design aimed to open Mars itself.

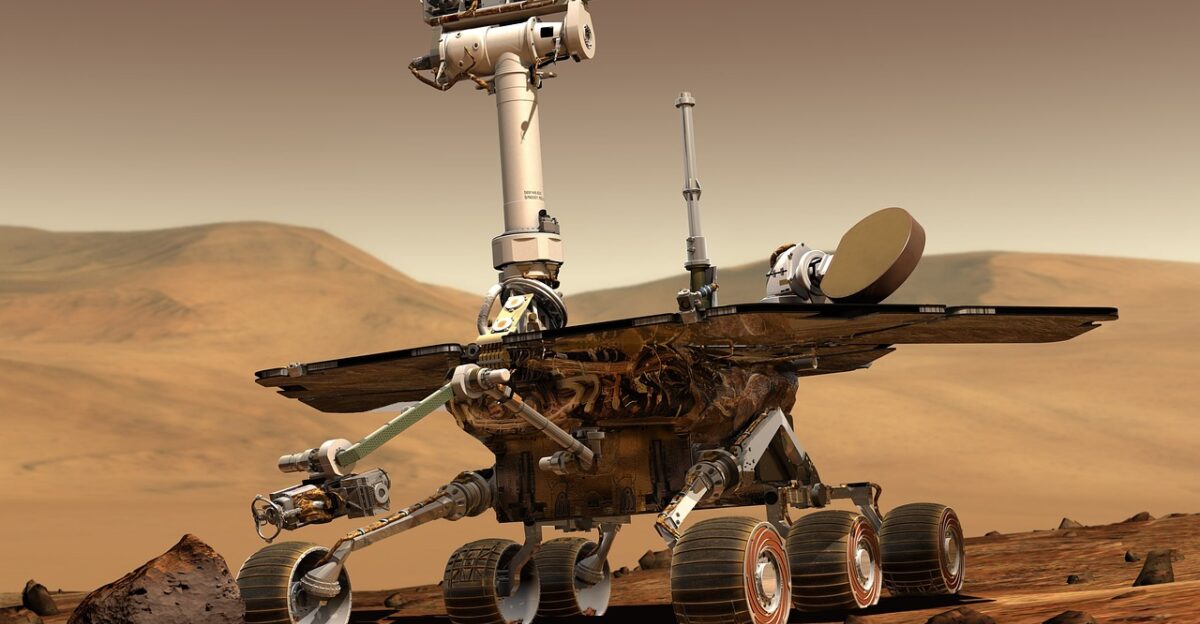

Packed With Tools For Real Science

Mars 3 paired a 3,440-kg orbiter with a 1,210-kg lander built to survive entry and operate on the surface. The lander carried 2 TV cameras, a mass spectrometer, temperature and pressure sensors, wind detectors, soil analysis gear, and a mechanical scoop to search for organics. It also included a 4.5-kg rover with skis and a 15-m tether. Yet one unplanned vulnerability remained.

The Launch Window That Raised Stakes

The 1971 Mars window offered an unusually favorable alignment, and the Soviet Union had been chasing similar opportunities since 1960, often ending in disaster. In the same window, NASA launched Mariner 9, just days after Mars 2 and Mars 3, turning the timing into a competition. Pressure mounted as Proton-K rockets sent Mars 2 on May 19 and Mars 3 on May 28 toward Mars. When the arrival came, nature had other plans.

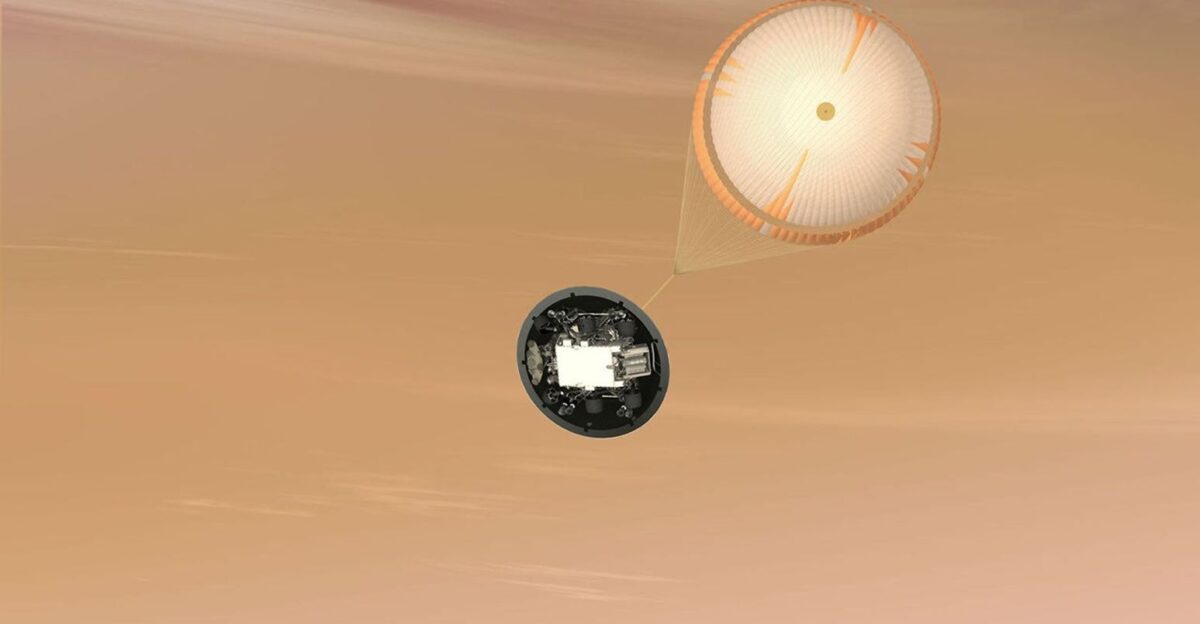

A Descent That Barely Made Sense

On December 2, 1971, Mars 3’s descent module hit the Martian atmosphere at 5.7 km/s. A heat shield slowed it, then a drogue parachute pulled out a main 15-m canopy. Mars’s thin air wasn’t enough, so at about 30 m altitude and still around 90 m/s, a retro-rocket with 10,000 kg thrust fired for 1 second. Touchdown came about 3 minutes after entry.

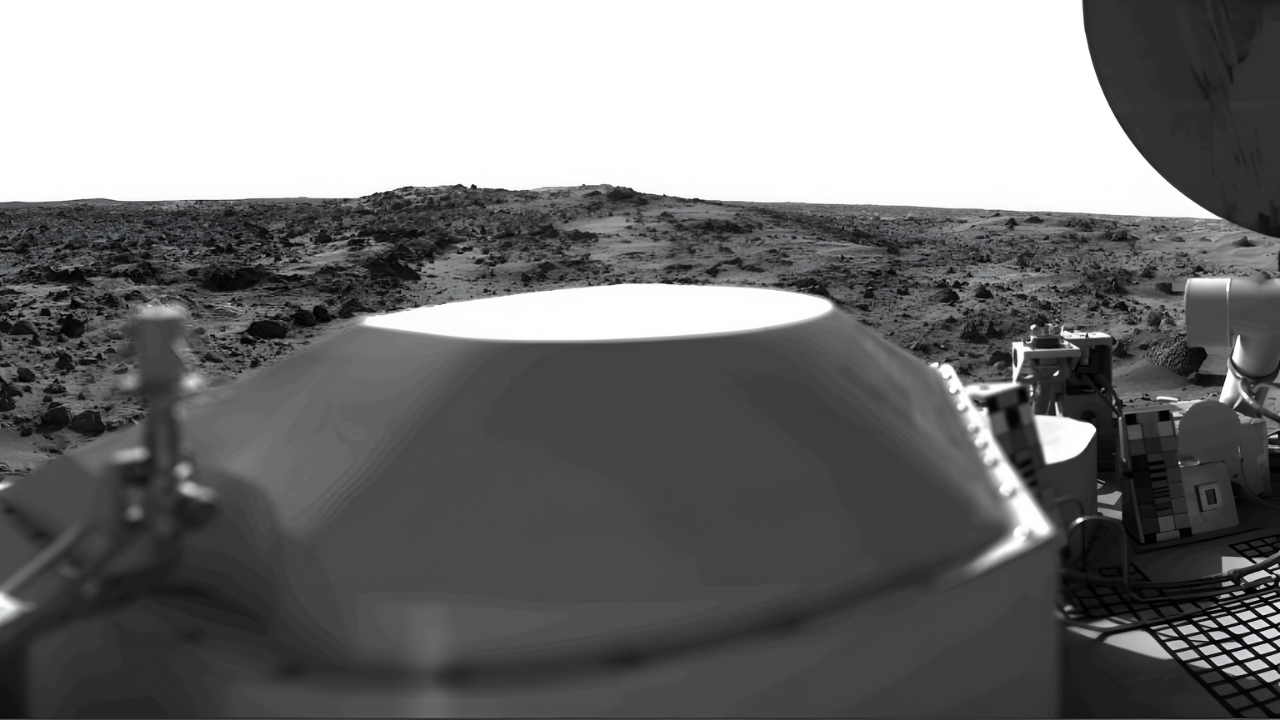

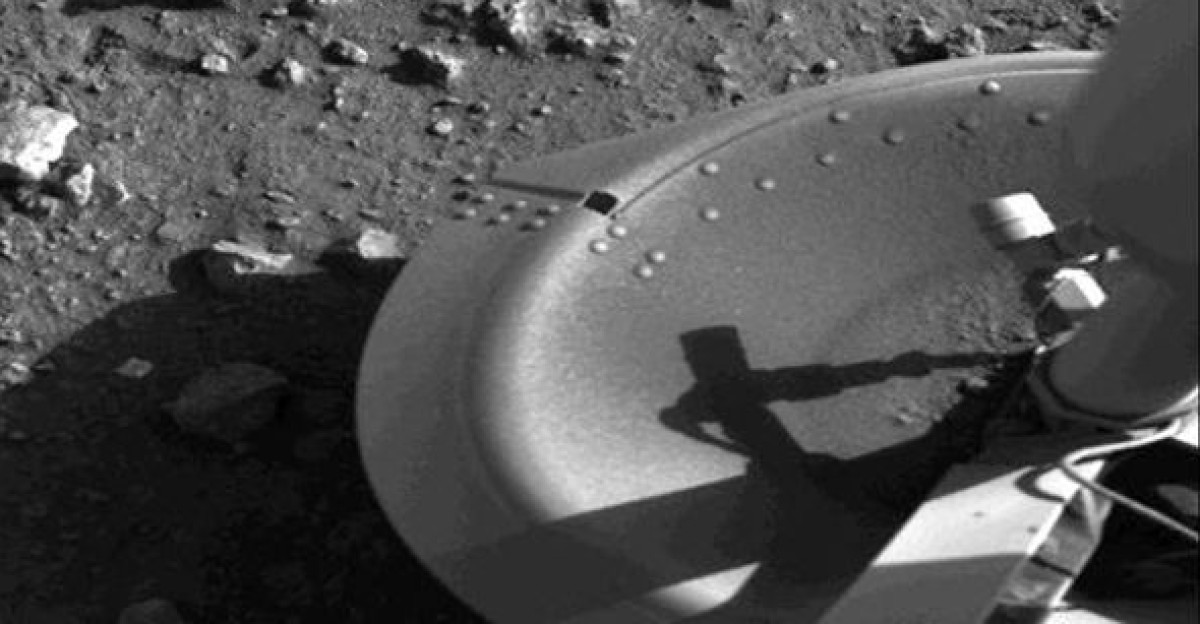

The Moment The Petals Opened

After landing, 4 triangular petals opened to right the spacecraft and expose instruments to the surface environment. This simple mechanical action mattered because it stabilized the lander for imaging, sensing, and communications. It also marked the point when Mars 3 shifted from surviving entry to starting science operations. For Soviet controllers, it was proof the design worked under real Martian conditions. Yet the real test was the link home.

90 Seconds That Looked Like Victory

Mars 3 initialized its systems after touchdown, and 90 seconds later began transmitting to the orbiter overhead, which relayed signals to Earth. Controllers in Moscow watched as cameras powered, soil instruments warmed, and sensors began producing readings. After more than a decade of Soviet effort, it appeared the world’s 1st controlled landing on another planet would deliver surface science. Then everything ended so abruptly it felt unreal.

“There Was A Gray Background”

“The transmission of panoramic images of the Martian surface recorded on the magnetic tape was initiated,” V.G. Perminov recalled. Signal strength was so high an engineer ordered it reduced. Data flowed, then both telephotometer systems failed almost instantly. Only 79 scan lines returned, a partial first surface image. “There was a gray background with no details,” Perminov wrote. Could 20 seconds really be all Mars allowed?

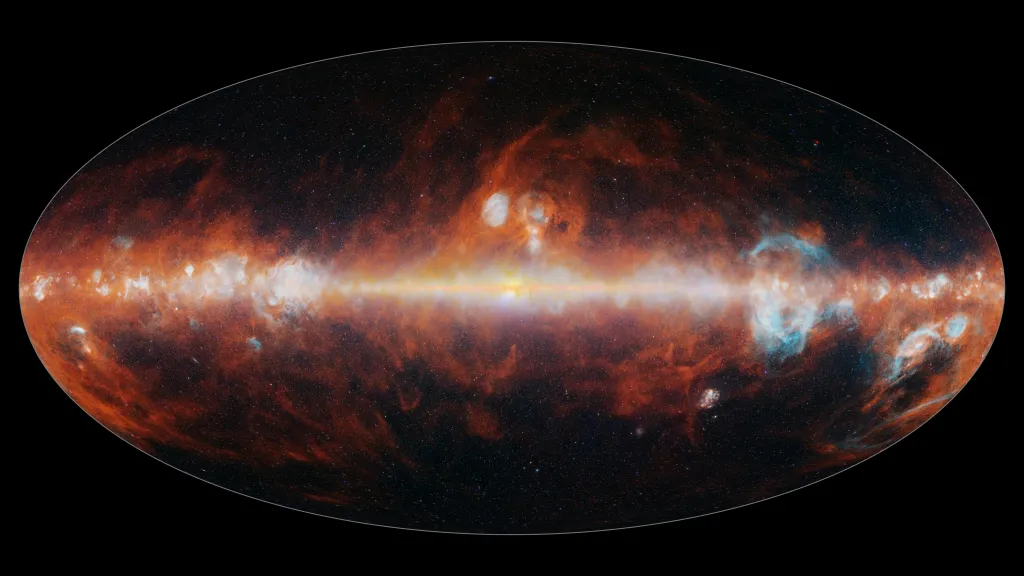

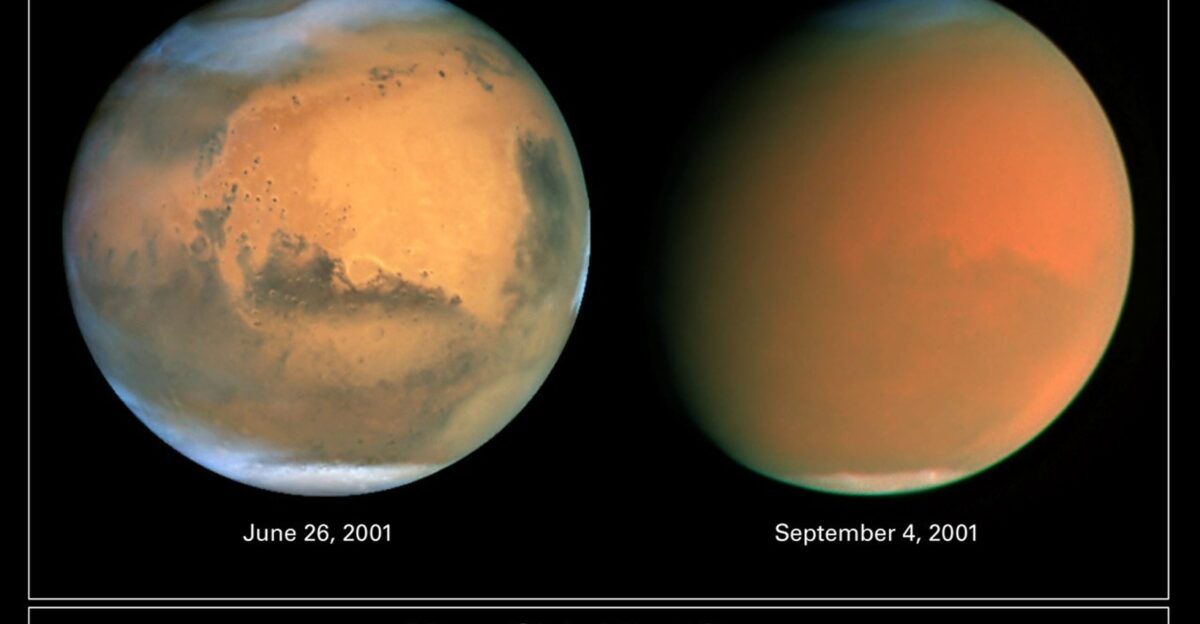

A Planet Hidden By A Single Storm

Soviet planners did not realize Mars was in one of the most violent dust storms ever recorded. When Mariner 9 arrived 13 days before Mars 3, it found Mars under “a planet-wide robe of dust, the largest storm ever observed.” Winds over 300 km/h lofted dust high enough to hide the surface globally. Mars 2 and Mars 3 could not adapt because their software was preprogrammed. The storm held another secret.

The Failure That Made No Sense

“Why did two telephotometers working in independent bands simultaneously fail within a hundredth of a second?” Perminov asked. “We could not find an answer to this question.” Weeks of telemetry review produced no clear mechanical explanation that could strike 2 independent systems at nearly the same moment. Perminov even recalled a World War II case where a Lebanese dust storm disrupted British radio signals through electrical interference. Was Mars doing something similar?

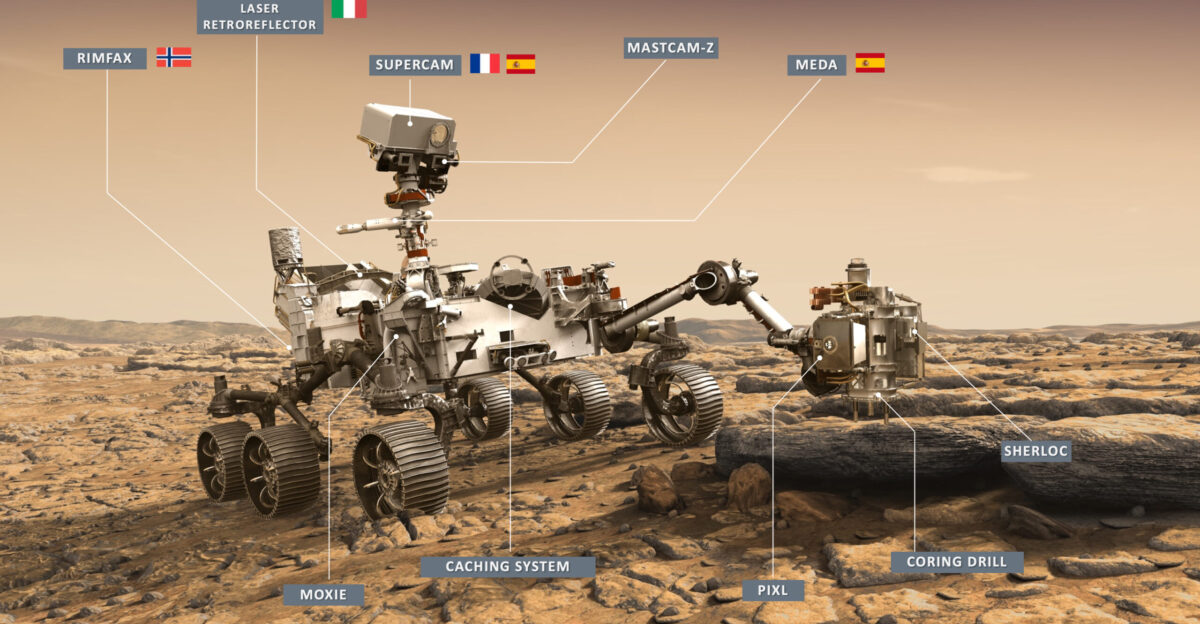

“Could It Have Been An Electrical Discharge Event?”

Mars 3’s fate gained a new explanation last month, when NASA’s Perseverance rover, using its SuperCam microphone, detected electrical discharges associated with Martian dust devils and storms. Scientists described brief electromagnetic interference followed by an acoustic shock signature, consistent with mini-lightning from charged dust grains. Ralph Lorenz reflected: “Something changed in 20 seconds. Could it have been an electrical discharge event? I don’t think we can rule that out.” Yet the orbiter still mattered.

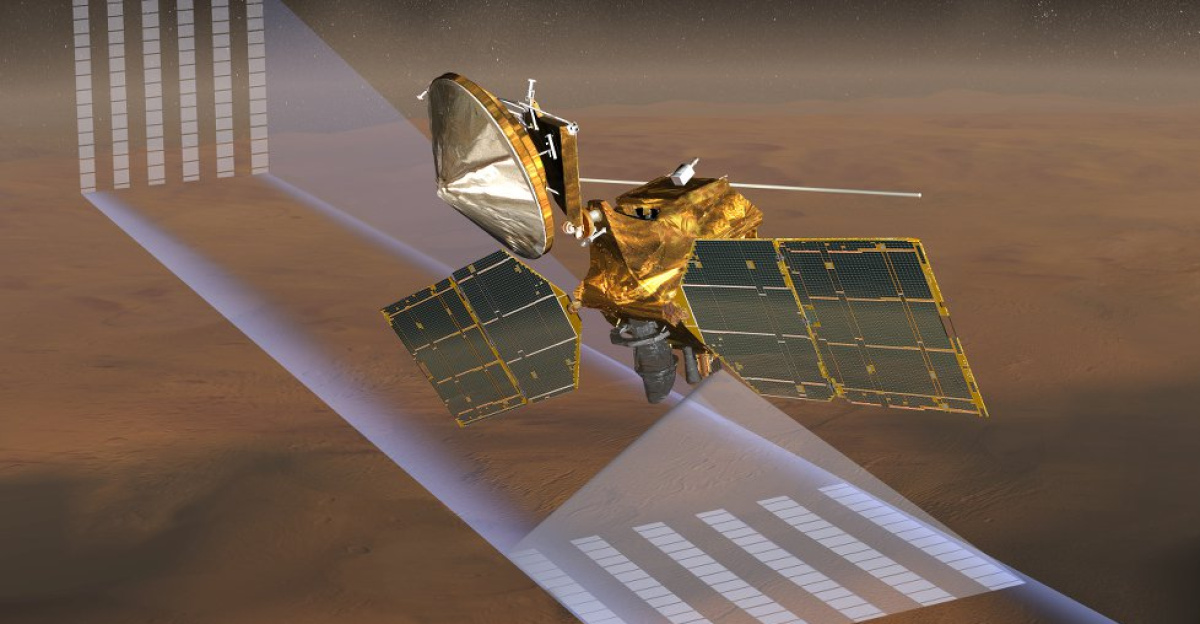

The Mission That Quietly Worked In Orbit

While the lander died quickly, Mars 3’s orbiter operated for 8 months. A partial fuel loss prevented its intended 25-hour orbit, yet it achieved an elliptical 12-day orbit and returned key science. Along with Mars 2’s orbiter, it delivered 60 photos and atmospheric measurements, including mountains up to 22 km high, temperatures from −110°C to +13°C, and water vapor about 5,000 times less than Earth’s. Still, few people heard much about it.

Why A Historic First Was Buried

The partial image was kept from public view until the late 1980s, when glasnost encouraged openness. By then many Soviet scientists had dismissed it as “a gray background with no details,” possibly noise. More damaging was institutional culture: failed missions were minimized, achievements filed away, and public celebration avoided. Unlike NASA’s detailed reporting, Soviet practice often treated failure as shameful. Mars 3’s first landing became a hidden milestone. Yet silence could not last forever, could it?

42 Years With Hardware Sitting In Plain Sight

For more than 4 decades, Mars 3’s hardware lay scattered across Ptolemaeus Crater, largely unobserved and absent from Western narratives. In 1976, NASA’s Viking 1 1976 became widely credited as the first successful Mars landing, pushing Mars 3 out of public memory. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the engineers aged and the records were dispersed. The lander became a ghost story in space history. Then a 2007 NASA image changed the odds.

The 1.8 Billion Pixel Clue

In November 2007, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter photographed the predicted Mars 3 landing area with HiRISE. The image contained 1.8 billion pixels, enough detail to require approximately 2,500 typical computer screens for full viewing, yet it was simply archived among countless reconnaissance products. No dedicated team was hunting for Mars 3 remains at the time, so the evidence sat unnoticed in a vast database. One person eventually decided that was unacceptable.

A Crowdsourced “Patriotic Quest”

Vitali Egorov, a St. Petersburg space journalist who ran a major Russian online community focused on NASA’s Curiosity rover on VKontakte, launched a search for Mars 3 using the HiRISE image. He split it into 20 sections and recruited about 4,000 volunteers for a “patriotic quest.” Within weeks, around a dozen participants flagged candidate objects matching expectations for Mars 3 hardware. What they reported looked too specific to ignore, but how could it be proven?

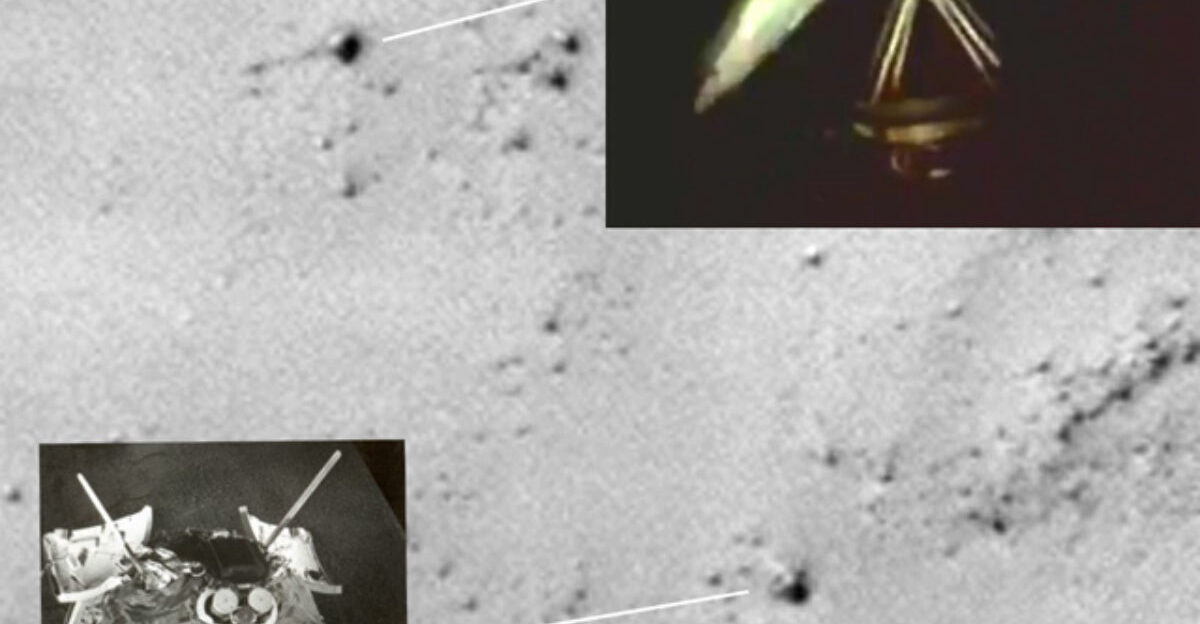

Pieces That Matched The Landing Sequence

Volunteers identified features consistent with Mars 3’s entry and landing: a bright parachute about 8 m across, a retro-rocket linked to the lander by a chain, and the lander body with petals open. The parachute would be 11 m if fully spread, but partial burial and folding fit the smaller apparent size. Researchers noted the objects had “a size and shape consistent with the expected hardware” and were positioned as the sequence predicted. Experts still had to confirm it.

A Rare Moment Of Shared Space History

Alexander Basilevsky of the Vernadsky Institute contacted Alfred McEwen, HiRISE principal investigator, requesting targeted follow-up. On March 10, 2013, HiRISE captured new color images with different lighting for 3D analysis. The parachute appeared “especially bright,” consistent with wind-driven dust cleaning over time. Basilevsky and Egorov also reached surviving Mars 3 engineers Arnold Selivanov and Vladimir Molodtsov for specifications. Would NASA publicly back the identification once evidence tightened?

“Alternative Explanations… Cannot Be Ruled Out”

“Together, this set of features and their layout on the ground provide a remarkable match to what is expected from the Mars 3 landing,” McEwen said, while noting that “alternative explanations for the features cannot be ruled out.” NASA’s April 11, 2013 announcement effectively revived Mars 3 as a physical artifact, found through collaboration that Cold War politics once made impossible. Americans imaged Soviet hardware; Russians helped interpret it. The rediscovery carried an emotional weight that surprised even its organizers.

“Mars Exploration Today Is Available”

“I wanted to attract people’s attention to the fact that Mars exploration today is available to practically anyone,” Egorov said. “At the same time, we were able to connect with the history of our country, which we were reminded of after many years through the images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.” The find became a bridge between eras, turning competition into shared curiosity. Yet Mars 3’s more profound lesson goes beyond pride: it reveals how fragile firsts can be.

The First Soft Landing Still Matters

Mars 3 remains the 1st controlled landing on another planet, even if its surface transmission lasted only 20 seconds. The mission’s abrupt silence likely came from an extreme dust storm and, as later evidence suggests, possible electrical discharges that overwhelmed communications. Its orbiter still returned major data, and its hardware was eventually rediscovered through international effort. As new rovers roll and crewed Mars plans advance, remembering Mars 3 restores a missing chapter of human ambition. Still, Mars keeps testing what we think we know.

Sources

NASA Mars Orbiter Images May Show 1971 Soviet Lander. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, April 11 2013

50 Years Ago a Forgotten Mission Landed on Mars. Astronomy Magazine, December 2 2021

Detection of Triboelectric Discharges During Dust Events on Mars. Nature, November 26 2025

The Difficult Road to Mars. NASA History Series Publication, April 2023