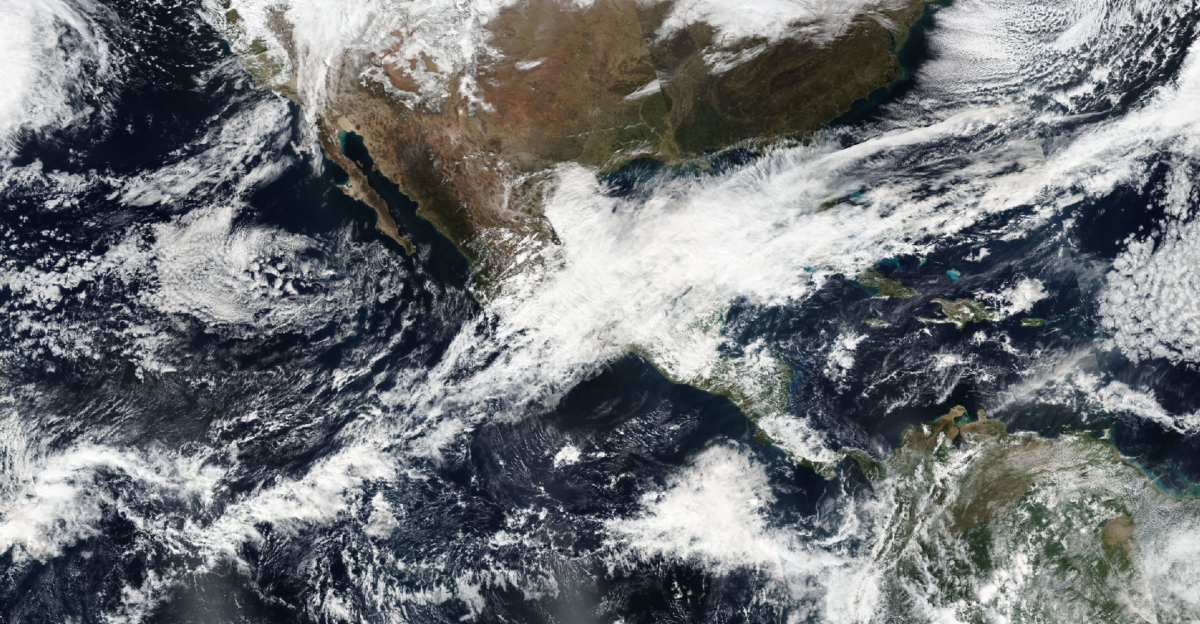

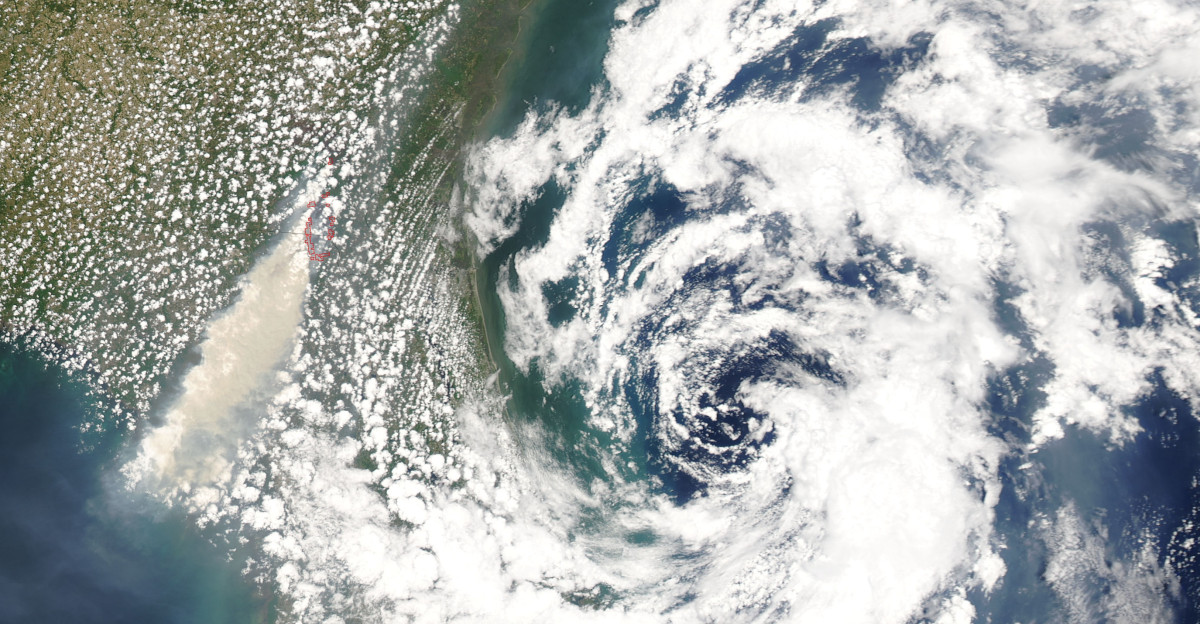

Meteorologists are tracking an exceptionally rare weather phenomenon this weekend: a potential tropical disturbance in the Eastern Pacific Ocean that, if it develops, would mark the first documented tropical system to form in January in recorded history.

The National Hurricane Center and AccuWeather are monitoring a mass of thunderstorms off Mexico’s Pacific coast, with a roughly 10 percent chance of becoming at least a subtropical storm by Sunday or Monday.

The Impossible Weekend Window

The Eastern Pacific hurricane season officially ended on November 30, more than six weeks ago. Yet ocean dynamics and upper-level wind patterns are creating what AccuWeather’s lead hurricane expert Alex DaSilva calls “a brief fighting chance” for subtropical storm formation.

The window is narrow: meteorologists expect the system to either spin up quickly this weekend or die in cold water by early next week.

Why This Matters: A Historical First

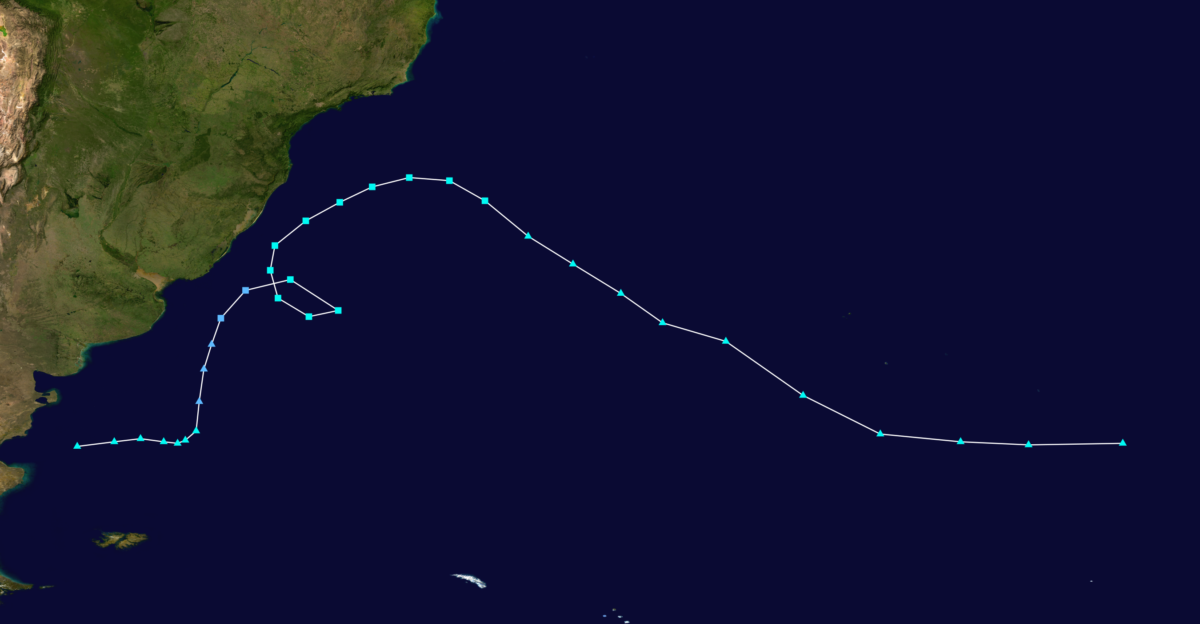

No tropical system has ever formed in the Eastern Pacific during January in the modern meteorological record. While the Central Pacific has produced rare January storms before, including Tropical Storm Ekeka in 1992 and Hurricane Pali in 2016, the Eastern Pacific in winter remains dormant.

DaSilva emphasized the rarity: “It’s exceptionally rare. The water temperatures are very cold during this time of year. So it’s really hard to get anything to form.”

What Forecasters Are Watching

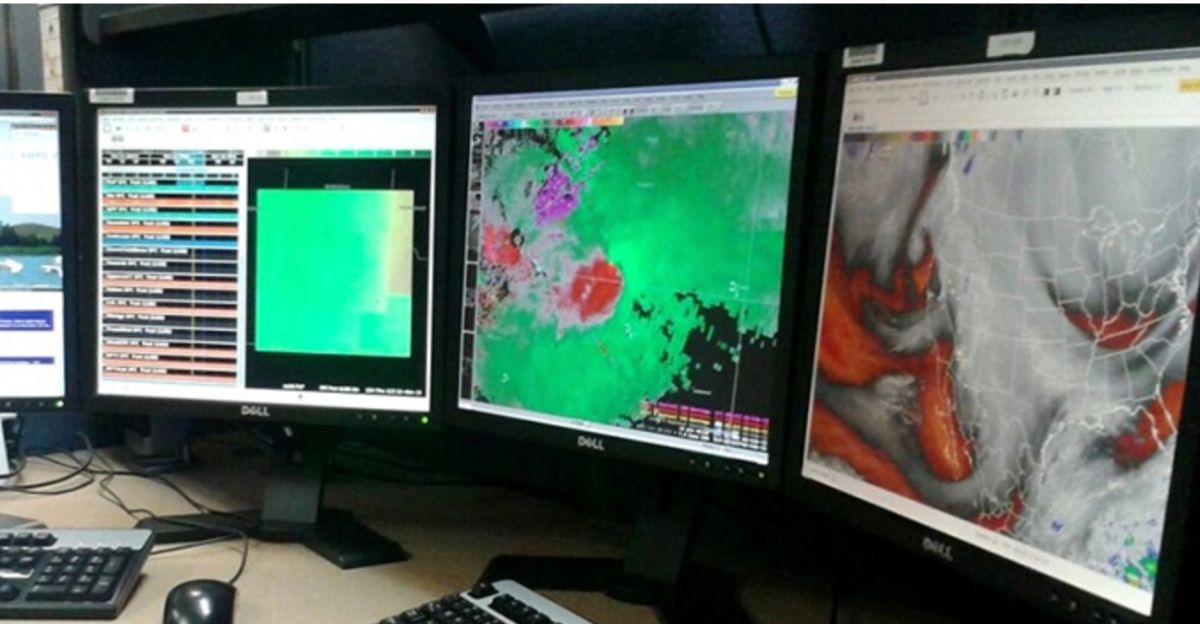

The National Hurricane Center, NOAA, and AccuWeather are monitoring a vigorous upper-level trough—a dip in the jet stream that could provide rotational energy to organize a low-pressure center.

Meteorologist Noah Bergren noted the system faces a “tall order” because cold ocean temperatures typically suppress tropical development. Yet marginally warm water combined with low wind shear has created unusual potential this weekend.

The Ocean Temperature Paradox

Eastern Pacific waters in mid-January are normally far too cold to sustain tropical systems. Ocean temperatures off Mexico’s coast typically hover in the mid-60s Fahrenheit, well below the 79-degree threshold required for tropical storm development.

Yet this year, a pocket of anomalously warm water exists where the system could potentially form. Colder waters will reassert themselves quickly, making any potential storm short-lived.

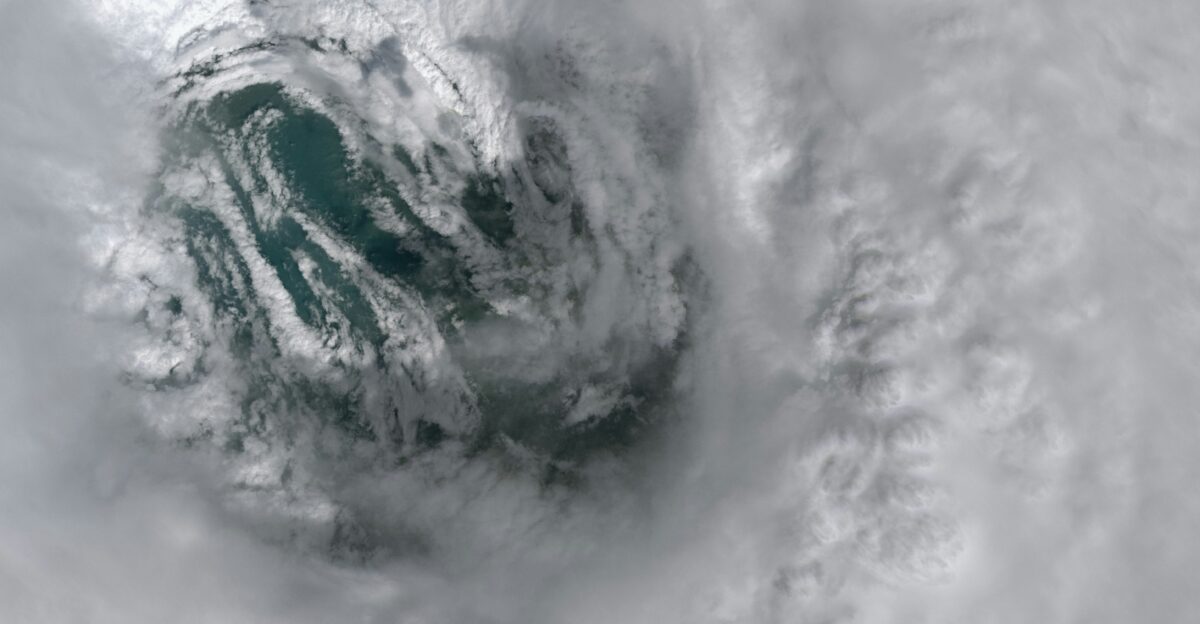

Subtropical Versus Tropical

If a system develops, it will almost certainly be subtropical rather than fully tropical. Subtropical storms form in cooler waters where warm-core tropical systems cannot, drawing energy from temperature contrasts between air masses.

Wind speeds—39 to 73 miles per hour sustained—mirror tropical storms, but the formation mechanism reflects the colder environment in which they emerge this time of year.

How Rare Is This?

The earliest Eastern Pacific tropical depression on record formed on April 25, 2020. The Central Pacific has seen rare January storms before. The Atlantic, with far more activity, recorded only a handful of January systems, including Hurricane Alex in 2016.

An Eastern Pacific January system would exceed even these rare occurrences in statistical improbability—a truly unprecedented event in 170-plus years of records.

Expected Impact: Low Threat to Land

Despite historical significance, forecasters stress minimal threat to populated areas. Mexico’s Pacific coast remains in a monitoring zone. Cold water will likely suppress intensification, and the system would dissipate quickly without organizing into a significant threat.

California’s coast is not expected to be affected. The primary impact would be on meteorological record books, not human safety or infrastructure.

The Engine Behind the Anomaly

Beneath this scenario lies a specific atmospheric driver: a vigorous upper-level trough—a river of cold air aloft curving southward into the Eastern Pacific. This feature creates rotation and lift, organizing scattered thunderstorms into a cohesive system.

When combined with low wind shear, it can spin up a surface low-pressure center even in marginally warm waters.

What Models Are Showing

Global forecast models from the National Weather Service and the European weather service show thunderstorms developing off Mexico’s coast this weekend. Most models simulate some organization potential, with a small subset suggesting subtropical storm development.

The spread among models—some showing formation, others dissipation—reflects why probabilities remain modest at 10 percent rather than higher confidence.

The 48-Hour Race Against Time

From Thursday through Monday, meteorologists will monitor atmospheric models that update every 6 hours. If the system develops, it will do so rapidly—likely spinning up from organized storms to subtropical storm status within 24 to 36 hours.

By early next week, the upper-level trough will move inland, and cooler waters will reassert dominance. A definitive answer comes by Monday evening.

Expert Opinion: The “Fighting Chance” Perspective

AccuWeather, the National Hurricane Center, and meteorologists like Bergren have been transparent about uncertainty: this is a low-probability event with favorable conditions that may or may not align.

The phrase “fighting chance,” used repeatedly by forecasters, captures reality—a storm is possible but far from likely. Cold ocean temperatures remain the fundamental obstacle to sustained tropical development.

What Happens If It Forms?

If a subtropical storm develops, it will be named and track west or northwest across the open ocean, likely dissipating by Tuesday or Wednesday as it encounters colder water. Impact on land would be minimal to none.

Media coverage would be substantial—a first-ever January Eastern Pacific tropical system is a genuine historical moment in meteorological record-keeping.

What Happens If It Doesn’t?

If the system fails to develop, cold waters will have won, and the brief window for subtropical organization will have closed. The event underscores how close to possibility weather systems can form when atmospheric and oceanic conditions align, even when statistically improbable.

Either way, the weekend represents a pivotal moment in weather history.

Why Meteorologists Are Sounding the Alarm

The term “alarm” here is measured awareness, not panic. Forecasters are directing attention at the meteorological community: this is unprecedented and warrants close monitoring.

Mexico’s coastal populations should remain informed but not alarmed; the National Hurricane Center will communicate any escalation. The weekend represents a rare opportunity to document a first-ever event in real time.

Sources:

“Unprecedented January tropical disturbance possible in Eastern Pacific for first time in recorded history” — FOX Weather

“Unprecedented January tropical disturbance possible in Eastern Pacific for first time in recorded history” — AOL News/FOX Weather syndication

“‘Extremely Rare’ Storm Could Form This Weekend” — Newsweek