Millions of Americans rely on familiar pain relievers, cold remedies, snacks, and pet food without considering where they were stored before reaching store shelves. That trust was jolted on December 26, 2025, when federal regulators announced that nearly 2,000 everyday products had been recalled after inspectors found rodent waste and bird droppings in a single Minneapolis warehouse that supplied three states.

Scope of a Wide-Ranging Recall

What began as a localized warehouse issue quickly grew into one of the broadest recent recalls involving an FDA-regulated facility. Products from roughly 50 retail locations across Minnesota, Indiana, and North Dakota were affected. The recall list stretched to about 44 pages and nearly 2,000 stock-keeping units, covering seven categories overseen by the Food and Drug Administration: human and pet drugs, medical devices, cosmetics, dietary supplements, human food, and pet food.

Recognizable brand-name items such as Tylenol, Advil, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Haribo gummy candy, and Purina pet food were among those flagged as potentially exposed. The concern did not stem from manufacturing defects at those brands, but from how the products were stored and handled at a shared distribution point. A single facility had become the nexus for contamination risk across a diverse mix of medications, snacks, beverages, and animal feed, raising questions about how one link in the supply chain could compromise so many different product lines at once.

A Warehouse with a History

At the center of the recall was Gold Star Distribution, Inc., a long-established wholesale grocery distributor based at 1000 N. Humboldt Ave. in Minneapolis. For decades, Gold Star had moved shelf-stable foods, medications, and other goods from manufacturers into the Upper Midwest retail market, operating largely out of public view while playing a pivotal role in stocking neighborhood stores.

The facility was not unknown to regulators. In October 2018, the FDA issued a formal Warning Letter to Gold Star for nearly identical violations at the same site, including rodent activity, insanitary conditions, and structural problems such as a leaking roof that had allowed contamination of infant formula and other food products. The company was told to correct the issues. When federal inspectors returned in 2025, they again reported rodent excreta, rodent urine, and bird droppings in warehouse areas where drugs, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and other regulated items were stored. The recurrence suggested that early corrective promises had not translated into durable change.

Findings, Health Risks, and Who Was Affected

On December 26, 2025, the FDA publicly outlined its latest inspection findings, describing the Gold Star facility as operating under insanitary conditions. Products that had passed through the warehouse between August 1 and November 24, 2025, were considered at risk. In response, Gold Star initiated a voluntary recall of all products stored there during that period, with the FDA publicizing the action.

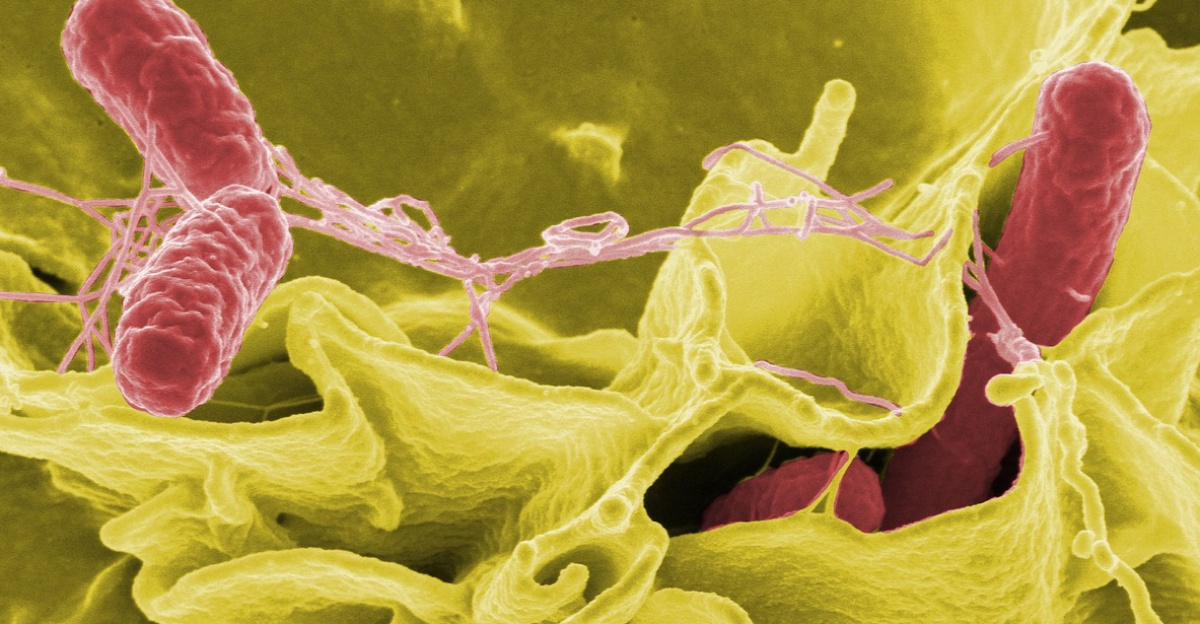

The conditions raised specific health concerns. Salmonella, a leading cause of foodborne illness in the United States, can trigger severe and sometimes fatal infection, especially in young children, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems. Leptospirosis, spread through rodent urine, is a bacterial disease that can cause fever, muscle pain, and in severe cases, organ failure. Regulators warned that even handling contaminated packaging could be enough to transmit these pathogens.

The Twin Cities and the broader Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan region, home to about 3.7 million people, were at the center of the distribution footprint. Grocery stores, convenience outlets, gas stations, and at least one daycare facility received products from the affected warehouse. Because the distribution window ran from August through November and the recall notice came at the end of December, many potentially contaminated items had likely been purchased, consumed, or stored in homes weeks before any warning reached the public, complicating efforts to connect later illnesses to the warehouse contamination.

Awareness Gaps and Systemic Strain

The recall also exposed a broader communication and oversight gap. Survey data presented at the May 2025 Food Safety Summit, cited by Rutgers University behavioral scientist William Hallman, indicated that only about 13% of Americans had ever used a government site to check for food recall information, and only about 3% subscribed to recall alerts. That means a large majority of consumers—approximately 87%—typically remain unaware that products they already purchased may be subject to a safety warning. In the Gold Star case, that translated into millions of people who may never learn that their pain relievers, snacks, or pet food were on the recall list.

Retailers across Minnesota, Indiana, and North Dakota were left to identify, pull, and dispose of affected inventory while fielding questions from customers. Some stores issued announcements or direct messages to loyalty program members, but most could not pinpoint which individual shoppers had bought the recalled goods. Major brands faced potential reputational fallout despite not being responsible for warehouse sanitation lapses. Smaller independent grocers had to absorb the time and cost of checking shelves against the extensive recall list.

Gold Star instructed consumers not to bring products back to stores or ship them to the company. Instead, customers were told to destroy affected items and then seek refunds by providing receipts or photographs as proof of destruction. That process placed much of the burden on individuals to compare their purchases with an extensive product list, dispose of items safely, and document the loss, a set of steps many people were unlikely to complete.

Uncertain Outcomes and Unanswered Questions

Regulatory filings emphasized that the recall was voluntary, a term that carries legal weight. Under FDA rules, companies typically initiate recalls themselves, even when inspections and agency findings trigger the action. Mandatory recalls, in which the FDA formally orders products off the market, remain rare. For many consumers, however, that distinction is largely invisible; any recall associated with the FDA is often perceived as a direct federal removal.

By early 2026, public records had not clearly resolved the future of Gold Star’s Minneapolis operation. It remained unclear whether the facility would be allowed to resume full activity after remediation, face extended closure, or be subject to more frequent inspections. The episode sharpened a set of lingering questions for regulators and industry alike: how often warehouses should be inspected, how to ensure timely follow-up when past violations are documented, and how to close the gap between recall announcements and public awareness. As supply chains grow more complex and centralized, the Gold Star case underscored how much consumer safety depends on facilities most people never see—and on inspection systems and communication tools that may not yet match the scale of the risk.

Sources

FDA.gov – Gold Star Distribution Recall Announcement

CDC – Foodborne Illness Data

Quality Assurance Magazine – FDA Announces Major Recall After Products Found at Risk

Bring Me The News – Filth, Infestations at Minneapolis Grocery Distributor

Fielding Law – Voluntary vs. Mandatory Recalls: What’s the Difference

Rutgers University Food Safety Summit – Consumer Recall Awareness Analysis (May 2025)