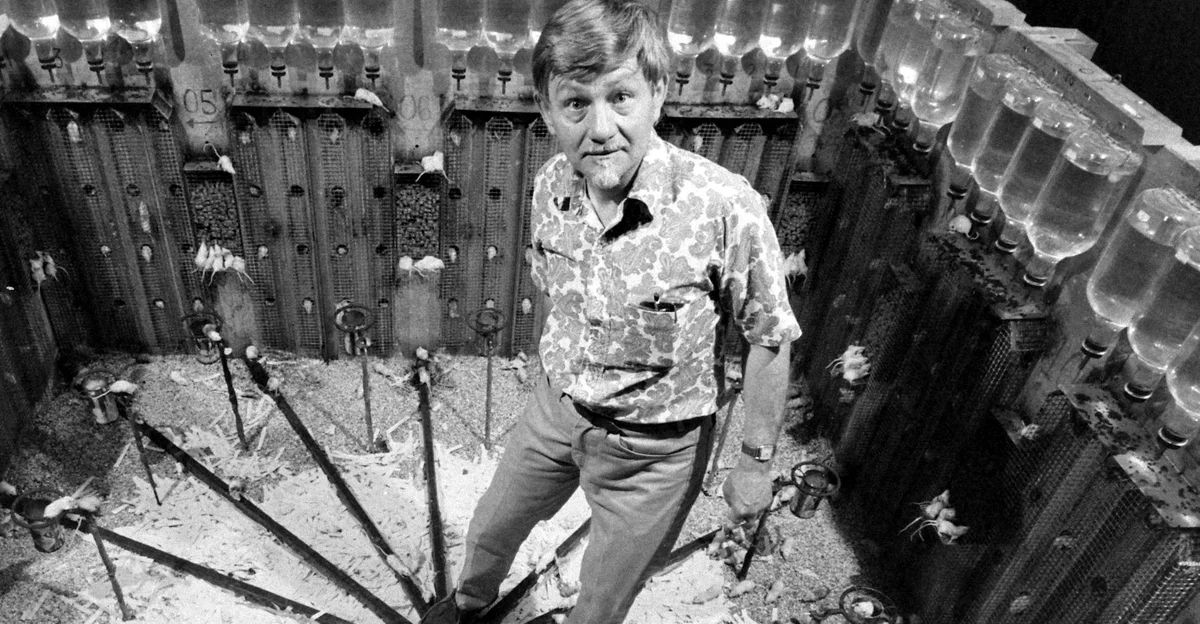

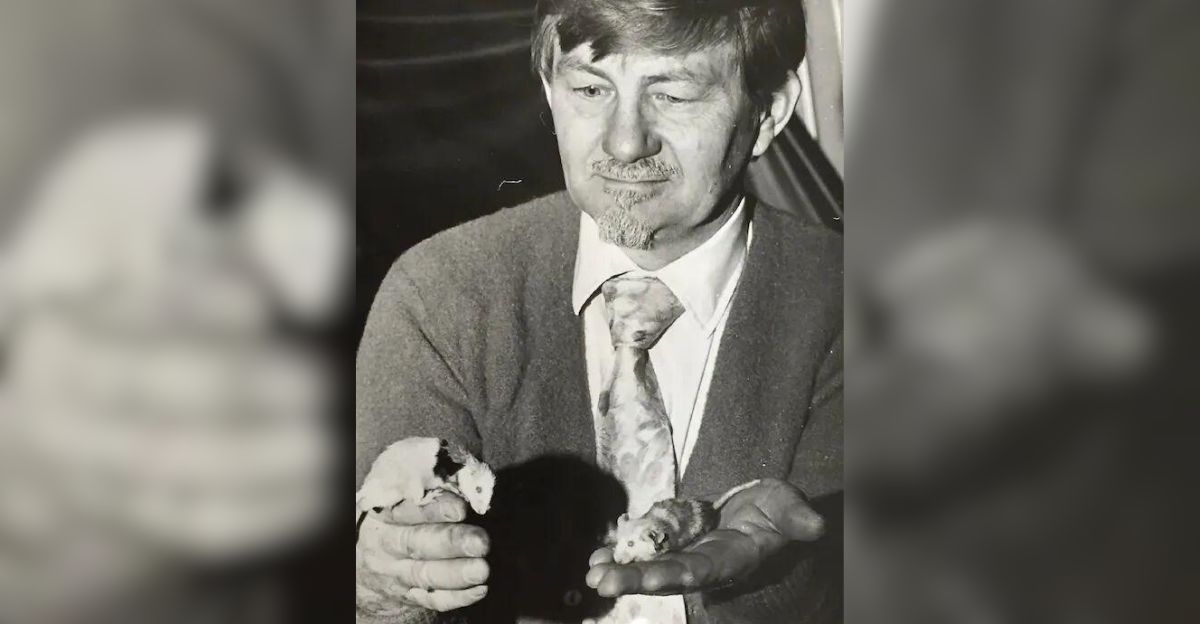

In 1968, Calhoun introduced 4 female and 4 male mice into a 2.7m×2.7m “rodent utopia,” complete with 256 nesting boxes, unlimited food, water and bedding.

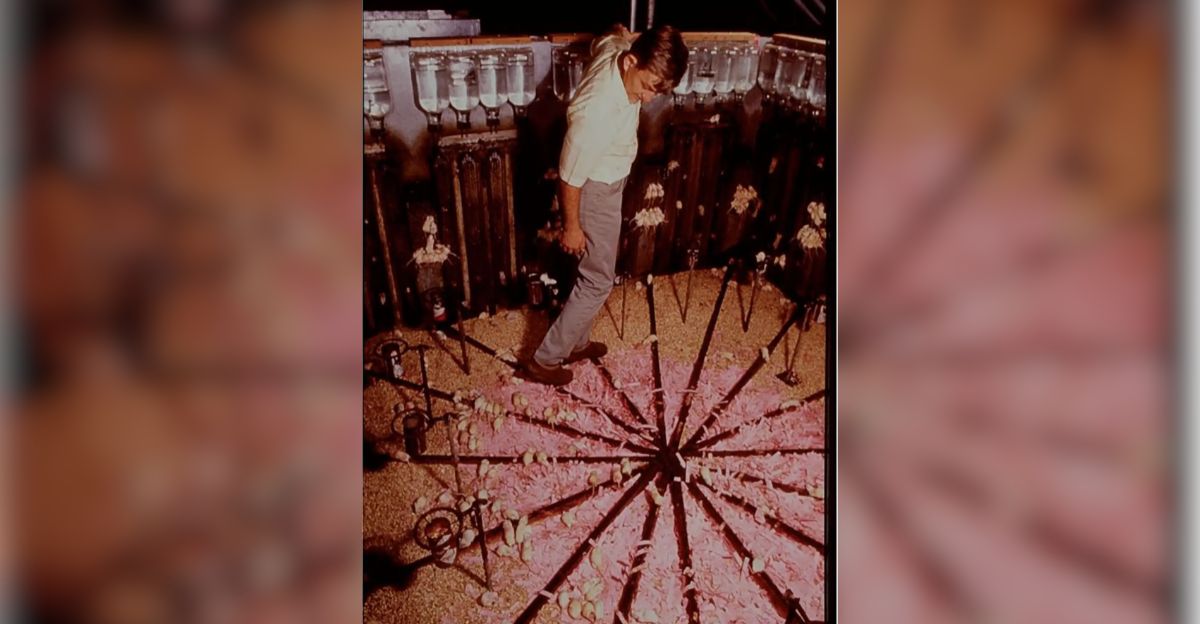

The colony doubled about every 55 days and by ~19 months it reached ~2,200 mice. Then, paradoxically, the population imploded: by around day 600 the birth rate collapsed and virtually no newborns survived.

By mid-1970, Calhoun found the once-thriving habitat a “dead city” of only a few dozen mice. Ultimately the final survivors died in isolation—an outcome Calhoun labeled a “behavioral sink”.

This haunting experiment offers a stark, science-backed warning of extreme crowding’s social toll.

Escalating Stakes

Calhoun didn’t view the mouse utopia as an isolated oddity. He treated his rodents as stand-ins for humanity, hoping the results would inform urban design and city planning.

He warned that life in ever-denser cities could “result in the complete devastation of humanity”.

Modern scholars echo these concerns: as Sam Kean records, the situation was meant to model what might happen in “an unnatural urban environment of ever-increasing density”.

Today’s experts and planners watch growing megacities warily, aware that shrinking social roles and scarce resources in crowded settings can trigger conflict and breakdown.

1970s Context

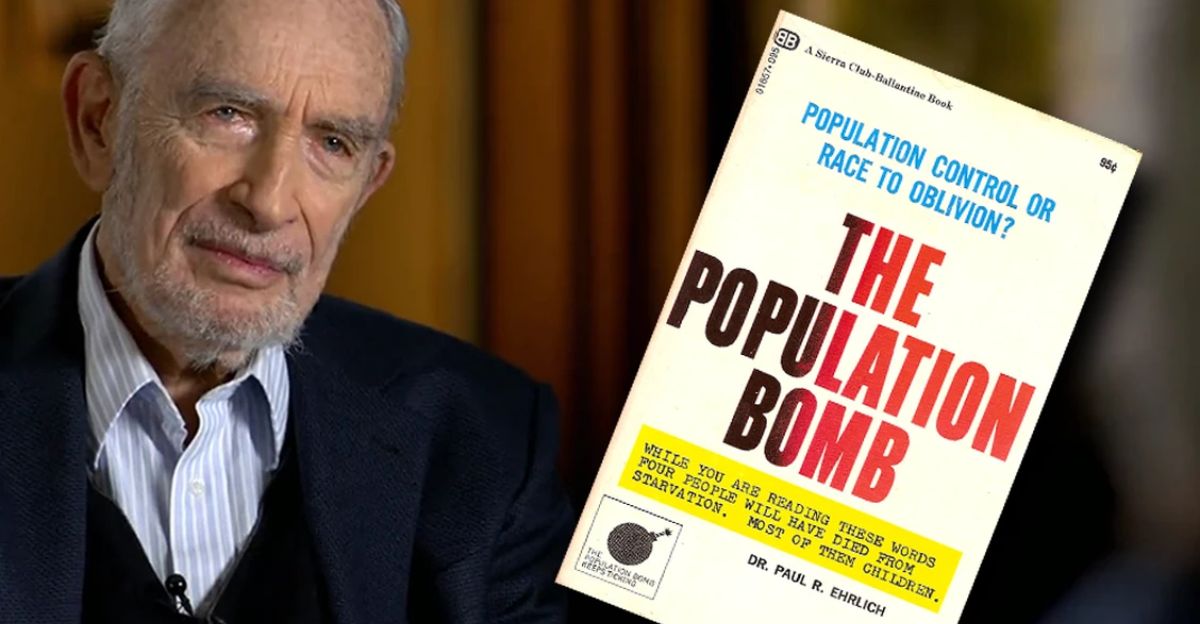

The late 1960s were awash in population panic. In 1968, Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, famously declaring “the battle to feed all of humanity is over,” and predicting widespread famine.

Doomsday scenarios followed in culture: films like Soylent Green (1973) depicted dystopian, packed cities wracked by crime and scarcity.

In this climate of Malthusian dread, Calhoun and others raced to test the limits of comfort.

He built his mouse utopias to explore whether extreme crowding would likewise unravel society, as his popular article warned.

Mounting Pressures

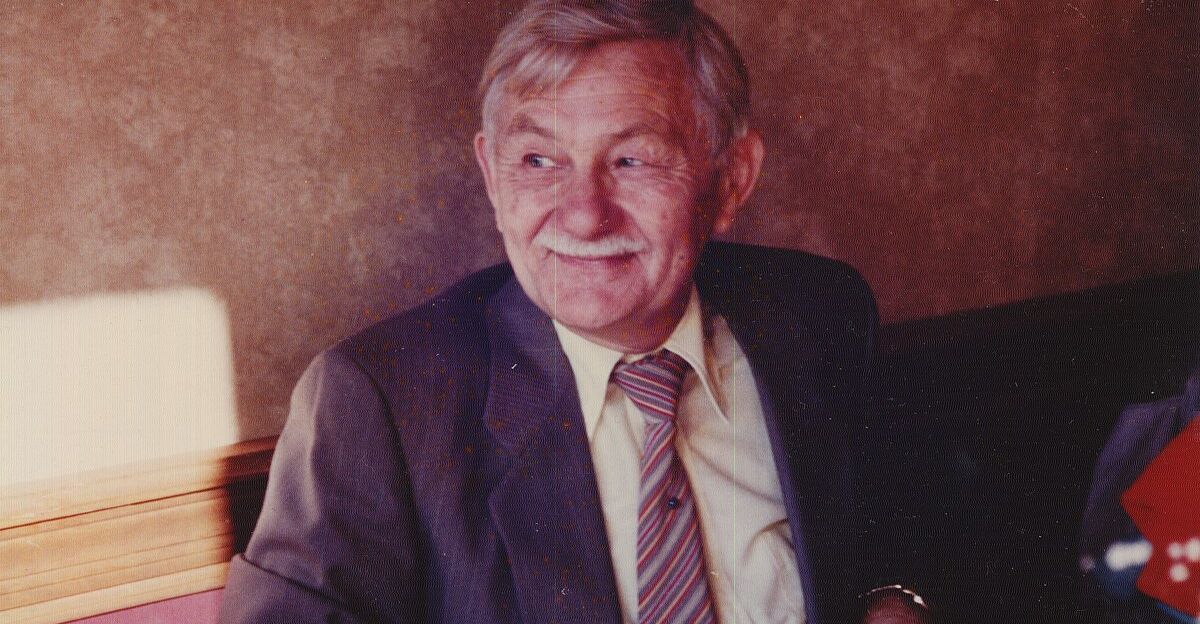

By 1968, Calhoun was poised for an unprecedented trial.

His first 24 rodent “utopias” always ended early due to space and time constraints, but this 25th attempt was meant to run its full course.

Calhoun had spent years refining these experiments, and this time, he packed his mouse habitat with every comfort to test the ultimate population boom.

Decades of smaller trials had hinted at trouble under crowding – now this final experiment would show whether even an idealized “Eden” could backfire.

Nugget Reveal

Calhoun introduced eight mice into this fully-stocked 2.7m cube with 256 nesting chambers.

The colony quickly boomed, but then collapsed.

Sam Kean describes what happened next: “These factors sent the mice society over a demographic cliff. Just over a month after population peaked, around day 600, no baby mice were surviving more than a few days,” and the last adults soon died.

In Calhoun’s words, the society devolved into a “behavioral sink.” This revealing episode – a thriving paradise turned ruin – was the critical nugget showing how abundance alone failed to prevent social collapse.

Regional Breakdown

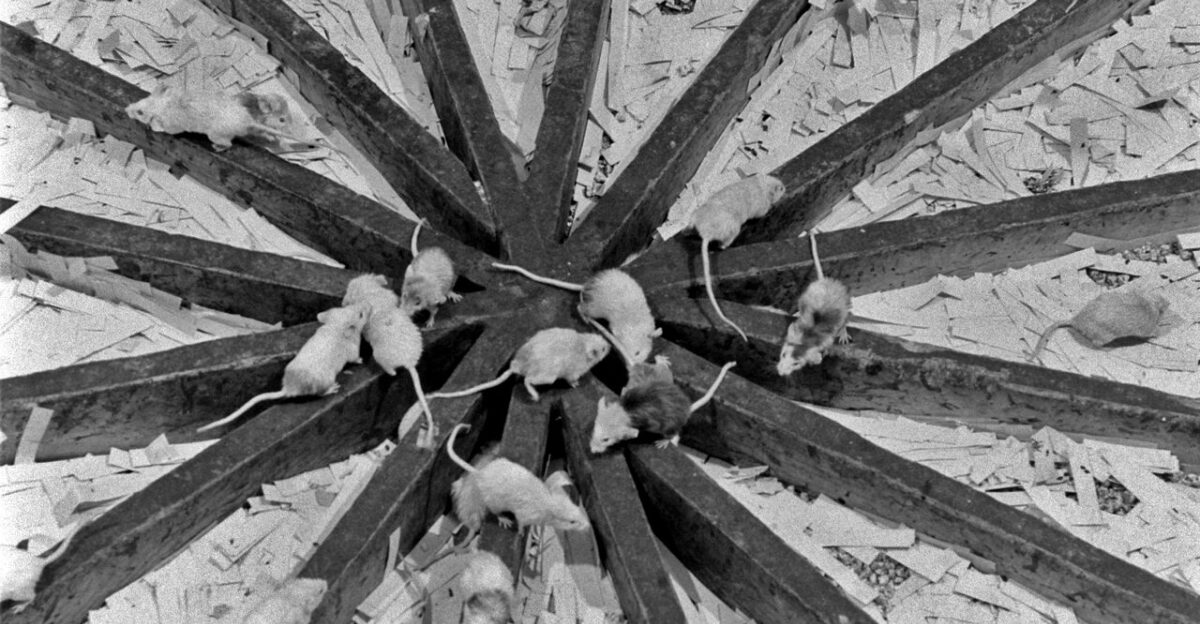

At first, Universe 25’s population growth was spectacular. But the social order soon fractured. Victorious alpha males clustered at the edges, defending exclusive nesting areas, while overwhelmed losers – the “dropouts” – huddled in the crowded center.

Another clique Calhoun called the “beautiful ones”, removed themselves entirely: pristine mice who ate, slept, and obsessively groomed in solitary luxury, refusing to mate.

With parental care collapsing, infant mortality in the common areas shot up to around 90%, even though food and shelter remained abundant everywhere.

The utopia had splintered into guarded camps, yet no group found a solution to the social chaos.

Human Stories

By late 1969 the colony was unraveling. Mothers abandoned or even killed their young, and even well-fed males frequently fought or cannibalized each other.

In one telling report, “few females carried pregnancies to term, and the ones that did seemed to simply forget about their babies… Sometimes they’d drop and abandon a baby while they were carrying it”.

As the last generation emerged, all breeding had ceased. Historian Ramsden notes Calhoun’s shock: “There’s no recovery – and that was what was so shocking to [Calhoun]”.

The lab mice had descended into despair – a bleak outcome that even their human steward found disturbing.

Cultural Impact

Calhoun’s term “behavioral sink” leapt from the lab into popular culture. His descriptions of an overcrowded collapse quickly became shorthand for urban decay.

In the 1970s, media seized on this dystopian tale: films like Soylent Green and sci-fi comics drew directly on the mouse-utopia story of a society unraveling under crowding.

These stories tapped into the era’s anxieties, cementing Calhoun’s experiment as an allegory.

Suddenly, his failed paradise was seen as a cautionary fable, symbolizing how even abundance can corrode social bonds and ethics when unchecked.

Policy Influence

Calhoun’s grim findings echoed in policy circles. Planners redesigned cramped housing projects to ease density, and international agencies promoted aggressive family planning – all under the specter of the mouse utopia.

Policymakers cited the experiment as scientific proof that overpopulation causes breakdown.

As historian Ramsden reports, Calhoun’s data were even “brandished… to justify population control efforts largely targeted at poor and marginalized communities”.

During the 1970s and ’80s, these interpretations helped drive controversial programs (from redesigned high-rise estates to one-child policies) aimed at preventing the very crisis Calhoun had observed in mice.

Mini-Nugget Reinterpretation

Mini-Nugget Reinterpretation: Today, scientists argue Calhoun misread Universe 25’s lesson. The new perspective is that collapse wasn’t caused by having “too much” of everything, but by who got it. Historian Edmund Ramsden puts it plainly: “the problem may not have been abundance itself—but unequal access to it.”

In Calhoun’s mice, a few dominant individuals hoarded the prime nest sites and feeders, leaving others chronically stressed.

The utopia thus mimicked a stratified society.

Rather than warning about abundance, Universe 25 becomes a warning about unequal distribution: the real “sink” was social exclusion and hoarded privilege, not mere population size.

Scientific Skepticism

Analysts note that Calhoun’s study was far from controlled science. It was essentially an observational trial – even Calhoun admitted it was “not normal science.”

Critics flagged missing data (no stress hormones measured) and unsanitary conditions in some pens, so many confounding factors were unmanaged.

Crucially, parallel human experiments showed no simple breakdown. In Jonathan Freedman’s classic studies, volunteers packed into smaller rooms showed no appreciable negative effect from increased crowding.

These results suggest that crowding’s impact hinges on social and psychological buffers – people handle density better when they retain personal autonomy and purpose.

Methodological Questions

Calhoun retired in 1984 but continued analyzing Universe 25’s records until his 1995 death, even as colleagues raised red flags.

They pointed out that the study was largely uncontrolled, with no quantitative stress data and no infection controls.

More troubling, by today’s standards, the experiment was unethical: countless mice endured preventable trauma.

The animals were deliberately kept in harmful conditions long after obvious suffering set in. Simply put, maintaining such a collapsing colony would now violate all animal welfare regulations.

Replication Attempts

Before Universe 25 finally ended, Calhoun made a last attempt to “rescue” the experiment. He removed several of the withdrawn “beautiful ones” and placed them in a new, uncrowded enclosure to see if they would recover normal drives.

They did not: the reclusive mice continued to refuse mating or interaction with their new peers, remaining inert until they died.

None of these rescue colonies produced offspring.

The entire experiment has never been faithfully replicated – partly because no one wants to (or legally could) reproduce such conditions.

Expert Outlook

Contemporary researchers emphasize the psychological dimension. Human reactions to density depend on autonomy, personal space, and social context.

In well-designed cities, millions can live densely if residents have choices and community roles.

As scientists note, crowding effects are “governed by… individual-specific factors,” not merely by head count.

In short, people can endure high density when they retain purpose and control – a balance Calhoun’s mice never had.

Future Questions

As the world urbanizes, Universe 25’s lessons still resonate – but in new ways. Earth today produces enough food for ~10 billion people, yet hunger and unrest persist, not from absolute scarcity but from unfair distribution.

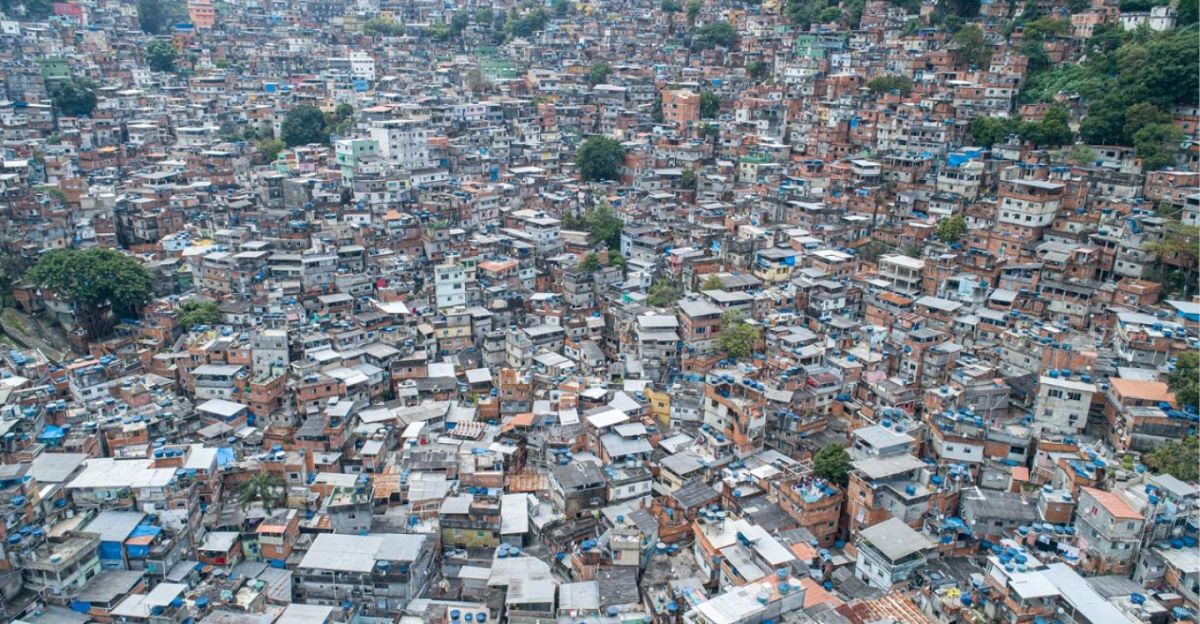

Our largest cities house millions successfully, but systemic inequalities create “pockets of dysfunction” (slums and disenfranchised districts) that eerily mirror Universe 25’s stratified zones.

Does social inequality create the same collapse Calhoun saw in mice? Urban planners and sociologists are now asking if policies that ensure meaningful opportunity for all may be the true antidote to the “behavioral sink” Calhoun warned about.

Political Implications

Here’s where it gets interesting: Calhoun’s mice were quickly pressed into human debates. Some warned that such social breakdown portended a “decline of the West” if welfare bred passivity.

Others seized the experiment as proof that unchecked growth “destroys family life,” citing Universe 25 as a dire warning.

Calhoun himself hoped the work would guide policy, noting that “no single area of intellectual effort can exert a greater influence on human welfare than…better design of the built environment”.

In other words, the solution might lie in planning smarter cities and roles, not just controlling population.

Global Parallels

Despite its small scale, Universe 25’s story resonates worldwide. Mega-cities and crowded slums mirror the isolation and conflict seen in the mice.

Many wealthy nations now have birth rates below replacement—a trend called a “spooky” parallel to the mice’s collapse.

In 1968, some scholars urged that humanity heed the mice’s warning: “We… take the animal studies as a serious model for human populations. Curb population growth—or else”.

Globally, then, Universe 25 serves as a lens on how population dynamics, inequality and environment interconnect.

Environmental Concerns

Our planet is finite: Calhoun’s mice had endless resources, but humanity does not. Primatologist Jane Goodall warns, “We can’t go on like this. We can’t push human population growth under the carpet”.

Conservationist Jonathan Porritt notes that as human numbers doubled, “wild animal populations have halved” – and had we curbed that growth, “biodiversity would be in a less perilous state”.

Futurist James Lovelock adds that “population growth and climate change are two sides of the same coin”.

Real-world ecosystems quickly strain under unchecked crowding.

Ethical Evolution

Today, we judge Universe 25 through a stricter lens. Calhoun’s methods — deliberately crowding and caging rodents — would violate modern research ethics.

Retrospectives note that his “constructed environments that caused harm” would now flout animal welfare standards.

Scholars also warn against over-simplification: science writer Sam Kean says Universe 25 “functions like a Rorschach blot — people see what they want to see,” and cautions that drawing lessons from it “can be a dangerous thing”.

Universe 25 ultimately taught scientists to uphold ethical oversight and interpret analogies with care.

Lasting Legacy

Half a century later, Universe 25 casts a long shadow in science and culture. Historian Sam Kean observes it “continues to fascinate people today — especially as a gloomy metaphor for human society”.

Even journalists have taken note: in 1968, Tom Wolfe dubbed New York City a “behavioral sink” in describing urban malaise.

Urban planners and policymakers still debate Calhoun’s legacy. He himself stressed that improving our “built environment” could greatly influence well-being.

Today, the experiment survives as a provocative parable – not a prophecy, but a reminder of how abundance, isolation and design shape social outcomes.