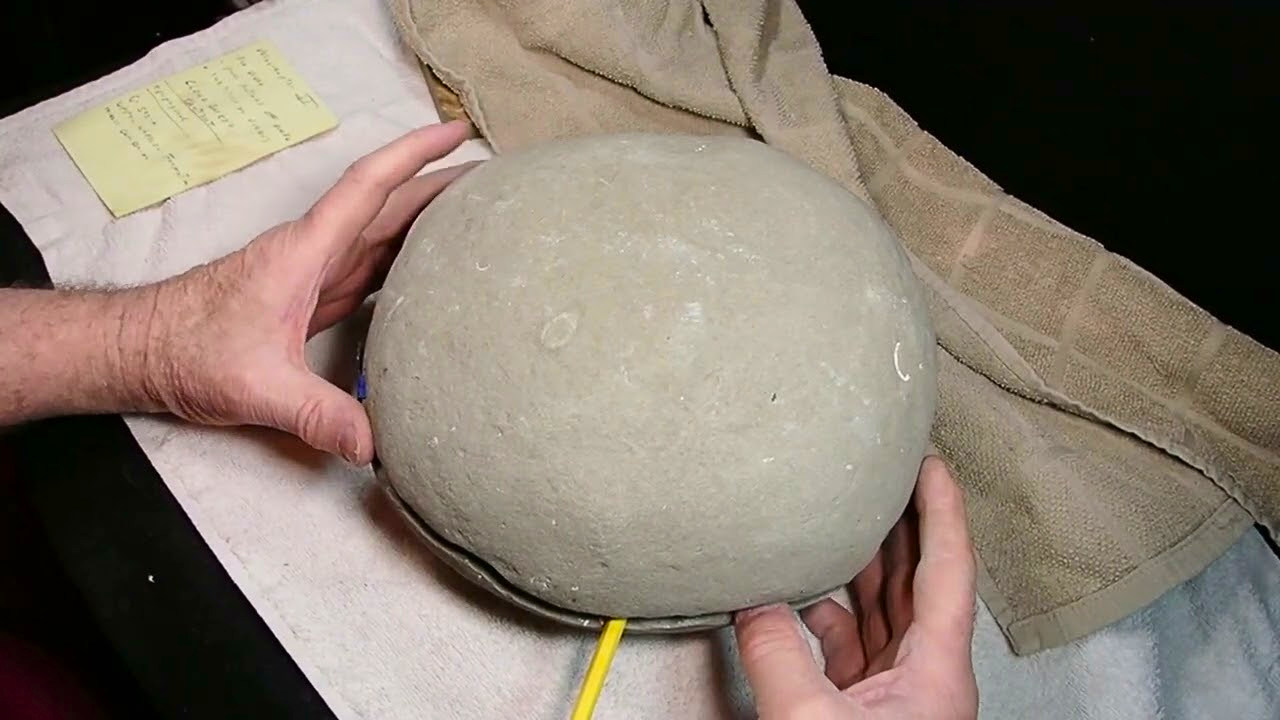

Three smooth, cannonball-sized eggs lay exposed along a roadside in Anhui Province, eastern China, when paleontologists stopped to examine them.

At first glance, they resembled fossilized dinosaur eggs—but fractures revealed something unexpected inside. Instead of preserved embryos, the interiors were filled with tightly packed calcite crystals that caught the light.

The unusual mineral structure immediately set these specimens apart from typical fossil finds, prompting researchers to investigate how biological material had been replaced entirely by crystal formations over deep geological time.

Racing Against Time

The Qianshan Basin has long yielded paleontological treasures, but dinosaur egg finds remain rare in its Cretaceous strata. Construction activity and natural weathering constantly threaten fossil sites across East China.

One of the three initially discovered eggs was lost during recovery—vanishing before scientists could thoroughly examine it.

Only two preserved specimens remained, yet their microstructural secrets were about to rewrite the understanding of ornithopod reproduction.

The Ornithopod Mystery

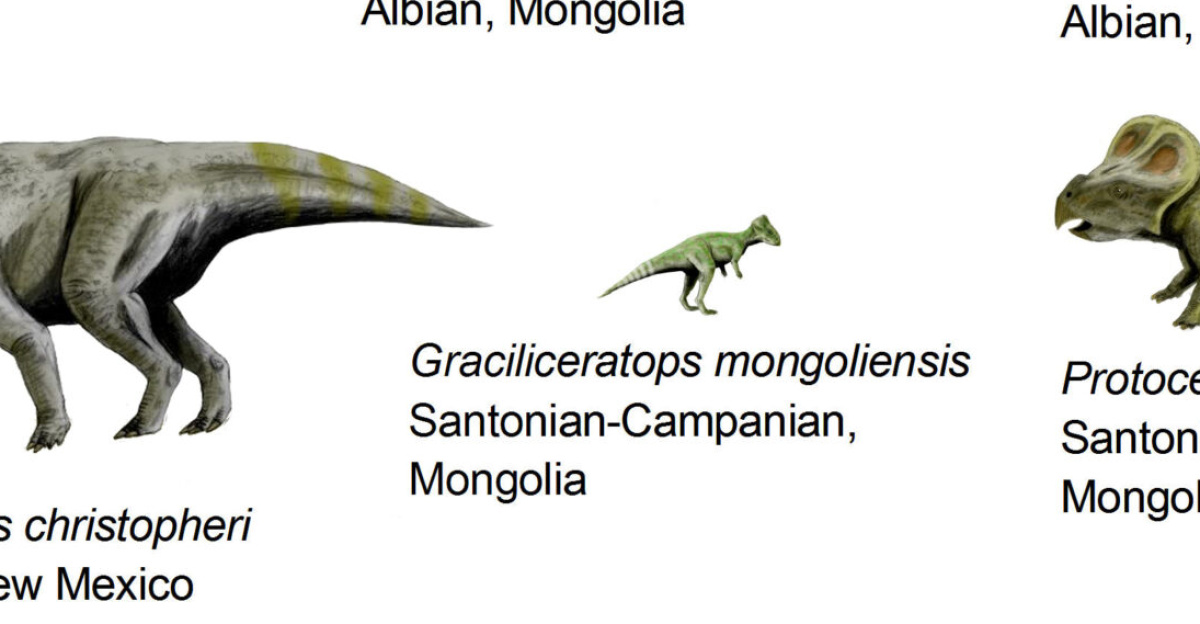

Ornithopods—duck-billed, herbivorous dinosaurs—dominated many Cretaceous ecosystems. These bipedal creatures ranged from five to thirty feet long, thriving across continents for over 100 million years.

Yet their reproductive biology remained fragmentary: paleontologists possessed scattered bone evidence but precious few intact eggs revealing how these dinosaurs nurtured their young. The Qianshan eggs promised to fill this critical knowledge gap.

Volcanic Preservation

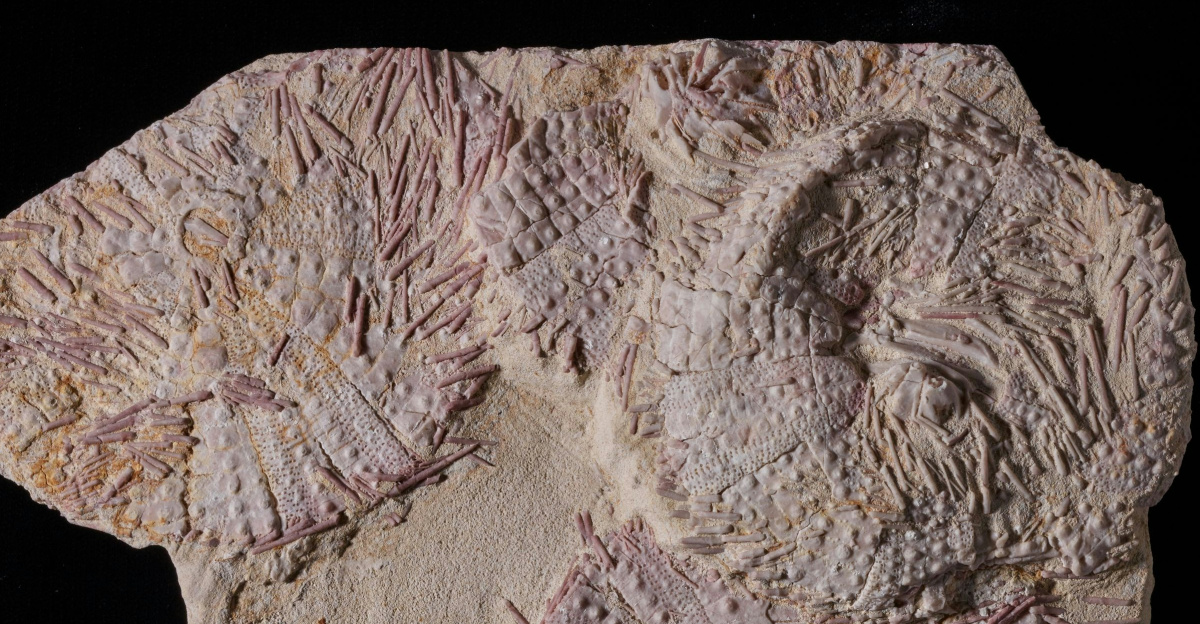

Eastern China’s exceptional fossil record is attributed to catastrophic volcanic activity during the Late Cretaceous. Pyroclastic flows and ash falls rapidly buried plants and animals, sealing them in oxygen-free environments that slowed decay.

This volcanic preservation created “time capsules”—some fossils retain stomach contents and feather impressions.

The Qianshan Basin shares these ideal conditions, which explains why crystal-filled eggs and embryo-rich clutches survive there, whereas they vanish elsewhere.

New Species Identified

In August 2022, lead researcher Qing He from Anhui University and the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology formally named the eggs Shixingoolithus qianshanensis—a new oospecies found only in the Qianshan Basin. (Oospecies refers to dinosaur classifications based solely on fossilized eggs, lacking skeletal evidence.)

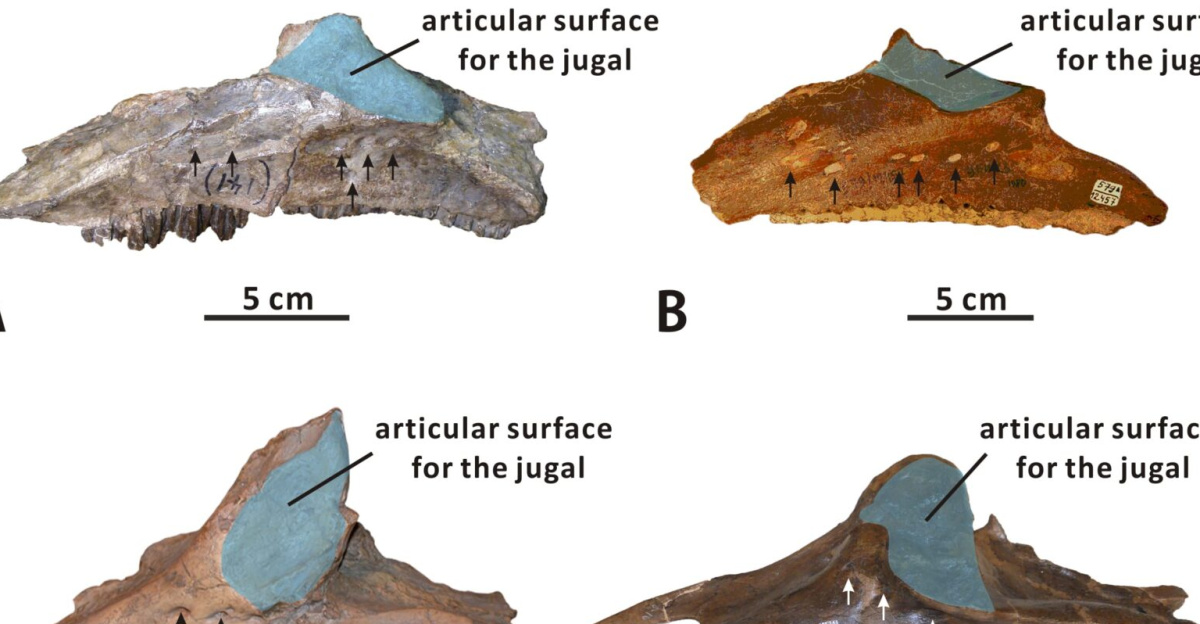

The publication in the Journal of Palaeogeography detailed how shell microstructure, thickness, and dense microscopic columns distinguished this species from all previously documented ornithopod eggs.

The Crystal Mechanism

Calcite crystals formed when calcium carbonate—a component of eggshells—separated from the fossilized structure over millions of years.

Mineral-rich groundwater infiltrated hollow egg cavities, depositing calcite and other minerals in slowly growing crystal formations.

This process paradoxically preserved the eggs: mineral coatings protected the delicate shell microstructures from further weathering and chemical damage, allowing paleontologists to examine their radial inner surfaces with clarity that was impossible in uncrystallized specimens.

Shell Architecture Reveals Identity

The radial microstructures on the eggs’ inner surfaces—specifically their tightly packed shell units and unusual size—proved diagnostic.

Shell thickness measured 2.3 to 2.6 millimeters, consistent with the family Stalicoolithidae, known for spherical, thick-shelled eggs.

These architectural features couldn’t belong to titanosaurs, ceratopsians, or other coexisting dinosaurs. The eggs’ geometry and composition uniquely matched ornithopod lineages, pointing to these herbivorous duck-bills as the likely parents.

Competing Fossil Sites

Other Chinese basins—Ganzhou in Jiangxi Province, Henan’s Xixia Basin—harbor similarly rich dinosaur egg deposits. Ganzhou has yielded hadrosauroid embryos, including “Baby Yang,” one of the most complete dinosaur embryos ever discovered (published May 2022).

These competing sites have captured headlines with embryo-filled clutches. Qianshan’s uniqueness lies not in the preservation of its embryonic form, but in crystal-filled spheres that reveal reproductive strategies through mineral replacement rather than bone.

A Cretaceous Moment Frozen

The eggs themselves date back to the Late Cretaceous period—approximately 70 million years ago, based on geological layer analysis of the Upper Maastrichtian Chishan Formation.*

They represent the final era of non-avian dinosaurs, a window into reproductive biology mere millions of years before the Chicxulub asteroid impact.

Understanding how ornithopods nested and reared young during this final chapter illuminates the mechanisms of extinction itself.

*Editor’s Note [Dec. 24, 2025]: This article originally stated that the Shixingoolithus qianshanensis eggs date to approximately 85 million years ago. The eggs are from the Upper Cretaceous Chishan Formation, which multiple scientific sources date to approximately 70 million years ago (Maastrichtian stage). We regret the error.

Three Lost Into Two

The collateral revelation: The loss of the third egg during recovery masked a potential goldmine of data. Had all three specimens survived excavation intact, paleontologists could have compared individual variation, clutch structure, and preservation differences among them.

Whether the egg was misplaced, damaged by excavation tools, or stolen remains officially unresolved. This silent casualty highlights the precariousness of paleontological fieldwork—discoveries can vanish before they’re documented.

The Standardization Puzzle

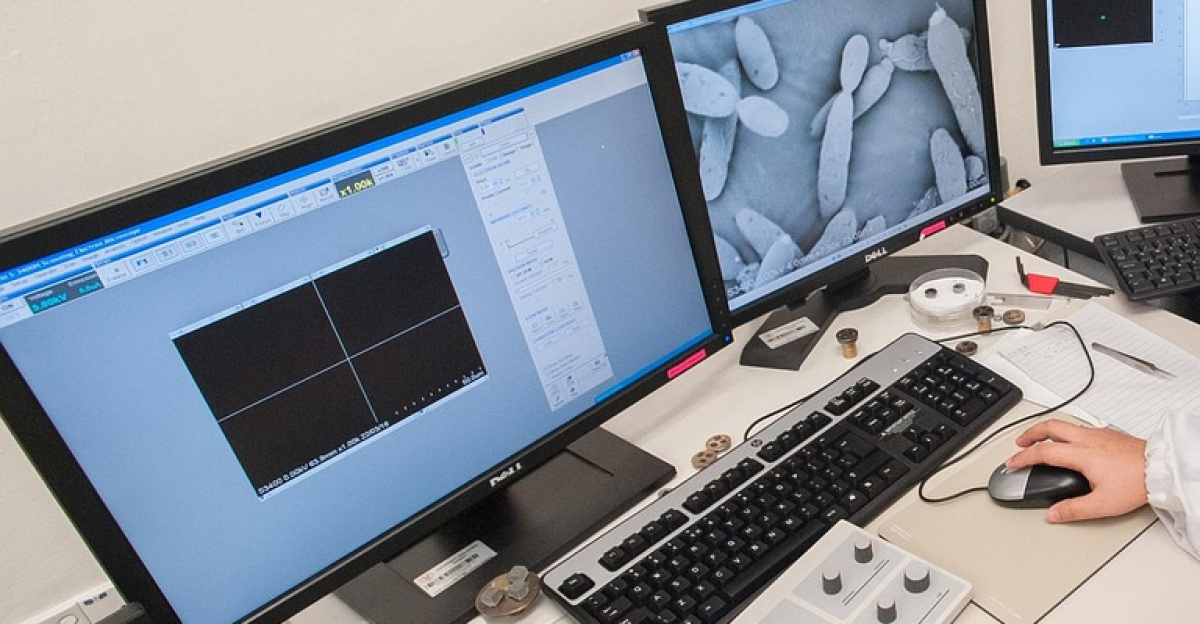

Classification of new oospecies demands rigorous methodological consistency. Lead researcher Qing He’s team measured eggshell thickness, analyzed microscopic column density, and examined radial section microstructure using polarized light microscopy and cathodoluminescence.

Yet standardized measurement protocols across Chinese institutions still lack universal agreement. Competing labs occasionally dispute whether subtle morphological differences justify the recognition of new species or represent intraspecific variation—a tension that could delay future Qianshan discoveries.

Institutional Recognition

Anhui University’s paleontology program has expanded capacity since the early 2010s, competing with better-funded institutions in Beijing and Nanjing.

Qing He’s appointment as lead researcher signals growing institutional investment in vertebrate paleontology.

Partnerships with the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Nanjing Institute have strengthened credibility, as findings published in peer-reviewed venues now command international recognition previously reserved for Western research teams. This institutional momentum drives future field expeditions and specimen analysis.

Expanding Qianshan Surveys

Following the 2022 publication, field teams intensified surveys in the Qianshan Basin. New quarrying and highway construction inadvertently expose fossil-bearing strata, creating opportunities but also risks. Paleontologists race excavation crews to recover specimens before machinery destroys formations.

At least two additional egg-bearing sites have been tentatively identified, although formal survey reports are still in press. A strategic partnership with local government agencies aims to protect high-priority zones.

Skepticism and Support

International ornithopod researchers have cautiously welcomed the classification of Shixingoolithus qianshanensis.

The eggshell microstructure data are robust, but the lack of embryonic remains or skeletal association continues to spark debate: Can eggs truly identify species definitively? Some paleontologists argue that identical eggs may derive from multiple sympatric species, rendering oospecies classifications potentially speculative.

Others counter that modern bird egg variation demonstrates the reliability of morphology—a productive disagreement that advances methodology.

Embryo Hunt

The critical unresolved question: Do similar eggs exist elsewhere in the Qianshan Formation—some with preserved embryos inside?

If discovered, embryonic remains could definitively link Shixingoolithus qianshanensis eggs to skeletal anatomy, eliminating taxonomic ambiguity.

Field teams now scrutinize unbroken eggs more carefully, employing computed tomography scanning before extraction to detect internal bone architecture. Such a discovery would transform this egg-only classification into a complete reproductive blueprint.

National Significance

China’s government recognizes paleontological discoveries as a form of soft power, demonstrating scientific leadership and custodianship of the Earth’s natural heritage. The discovery of Shixingoolithus qianshanensis is featured in state media and educational curricula, thereby elevating public interest in science.

UNESCO Global Geopark designations are increasingly incorporating fossil sites, creating incentives for their protection.

Anhui’s geotourism initiatives now market dinosaur sites alongside traditional attractions, channeling resources toward paleontological research and conservation.

International Collaboration Implications

The Journal of Palaeogeography, a peer-reviewed journal published by Springer, ensures that the discovery reaches global audiences instantly.

However, funding disparities persist: Chinese research teams often rely on government grants, while Western universities have access to diverse private and federal sources. International collaborative frameworks remain underdeveloped for paleontology, compared to physics or medicine.

The Shixingoolithus find demonstrates that breakthrough discoveries can emerge from non-Western institutions; yet, linguistic and logistical barriers still limit data sharing among paleontologists worldwide.

Climate Context and Evolutionary Pressure

The Late Cretaceous world experienced climate variability, with warmer intervals followed by cooler phases. Ornithopod eggs adapted to these fluctuations: shell thickness and porosity influenced gas exchange and thermal regulation.

The dense microstructure of Shixingoolithus qianshanensis eggs suggests adaptation to either arid climates (reducing moisture loss) or competitive nesting environments (higher egg robustness, preventing crushing in crowded clutches).

Understanding these reproductive adaptations reveals how ornithopods persisted until the asteroid strike 66 million years ago, providing evolutionary context for their vulnerability to extinction.

Technology’s Transformative Role

Modern paleontology leverages scanning electron microscopy (SEM), polarized light microscopy, and cathodoluminescence imaging—tools unavailable thirty years ago. These technologies revealed the microstructure of Shixingoolithus qianshanensis in unprecedented detail.

Future applications, such as high-resolution CT scanning and chemical isotope analysis of mineral infills, may unlock isotopic signatures that indicate nesting latitude or embryonic development duration.

The discipline is entering a phase where egg chemistry rivals morphology in diagnostic power, potentially revolutionizing oospecies classification.

The Broader Extinction Narrative

Shixingoolithus qianshanensis eggs vanished 66 million years ago when the Chicxulub asteroid—six miles across—struck the Yucatán Peninsula, triggering a catastrophic extinction that eliminated all non-avian dinosaurs within months.

These crystal-filled spheres preserve the final reproductive strategies of their species, frozen at the moment before annihilation.

They represent not failure but successful adaptation cut short by cosmic chance. In studying these eggs, paleontologists glimpse ornithopod life during Earth’s last moment of dinosaurs—a poignant reminder that evolutionary success offers no protection against planetary catastrophe.

Sources:

Earth com, December 19, 2025

Live Science, September 20, 2022

Journal of Palaeogeography, August 2022

PMC/NIH hadrosauroid embryo study, May 2022

NASA Science, January 2024

Natural History Museum London, November 2020