A geopolitical standoff between the Dutch government and China has triggered a semiconductor supply crisis, forcing major automotive factories to halt or reduce production.

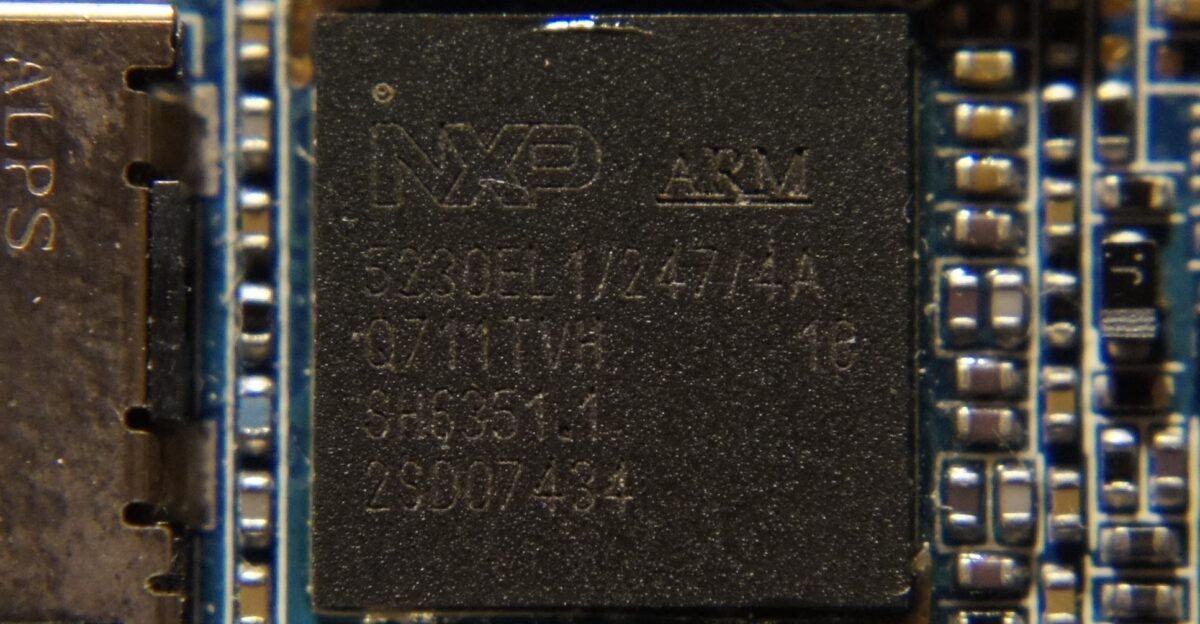

Nexperia, a Dutch chipmaker owned by the Chinese firm Wingtech, supplies essential low-cost semiconductors for critical automotive systems.

This crisis has exposed the industry’s vulnerability to geopolitical pressures, threatening thousands of jobs and potentially affecting hundreds of thousands of vehicles.

Although exports resumed in mid-November 2025, the underlying vulnerabilities within the supply chain remain unresolved.

Why Did the Chip Crisis Happen?

On September 30, 2025, the Dutch government invoked emergency powers to control Nexperia’s Netherlands headquarters, fearing technology transfer to its Chinese owner. China retaliated by halting exports of finished chips from its Dongguan factory in the Pearl River Delta.

This geopolitical standoff disrupted global supply chains, forcing automakers to scramble for alternatives. The crisis exposed how “mundane-yet-critical” low-tech semiconductors became strategic vulnerabilities that most companies had overlooked.

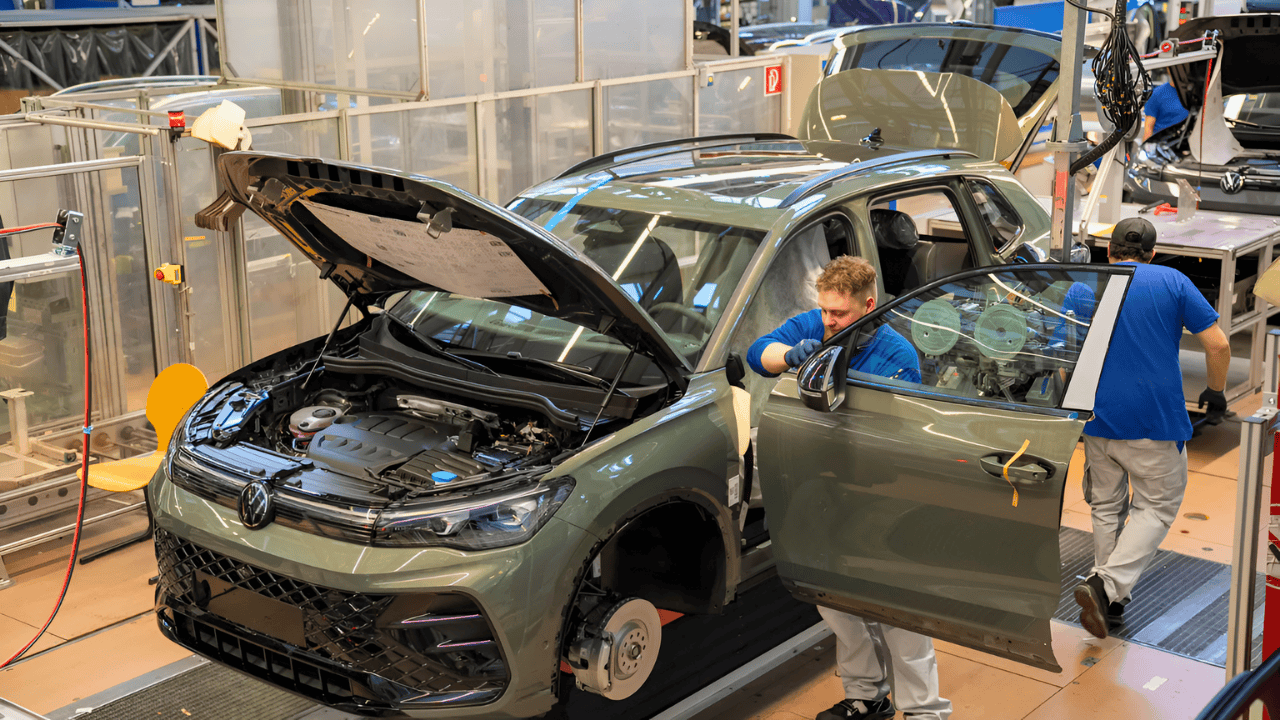

Production Cuts and Financial Impact

Nissan and Honda cut production at multiple facilities. Nissan’s Rogue SUV saw cuts of approximately 900 vehicles in mid-November.

Honda forecasted a 110,000-unit reduction and incurred ¥150 billion ($969 million) in costs—the largest single-company documented loss. The crisis disrupted nine major automotive suppliers: Nissan, Honda, Bosch, Volkswagen, Aumovio, ZF Group, Hella, JABIL, and other tier-2 suppliers, with some approaching complete shutdown before China allowed exports to resume in mid-November.

Dealerships reported dwindling inventories and warned of potential price increases if the crisis were to persist. The chip shortage directly threatened the availability and affordability of consumer vehicles.

Automakers Respond with Emergency Measures

Nissan, Honda, and Bosch immediately cut production and reduced factory hours. Bosch, ordering €200 million ($231 million) annually in Nexperia products, faced a shutdown within days before China resumed exports.

Toyota maintained output by utilizing stockpiles from its 2011 earthquake business continuity planning. Aumovio, ZF Group, and Hella similarly approached shutdown when exports resumed, exposing industry-wide supply chain fragility.

Penny Chips, Billion-Dollar Vulnerabilities

Nexperia supplies 40% of the global automotive semiconductor market—but not advanced chips. Instead, it manufactures low-tech components selling for fractions of a penny each. These control critical functions: car brakes, electric windows, and power modules.

Automakers spent billions securing advanced semiconductors while leaving penny-priced, irreplaceable components vulnerable to geopolitical weaponization. This blind spot exposed fundamental failures in supply chain strategy.

The Paradox: Netherlands Seized an Empty Building

The Dutch government controlled Nexperia’s Nijmegen headquarters while China controlled the actual Dongguan factory and finished chips, retaining production leverage.

This exposed an unprecedented weaponization of commodity components rather than advanced semiconductors.

The Netherlands “seized” an office building while China held the real power. Payment terms shifted: Nexperia required yuan instead of foreign currencies for resumed sales in late October.

Workers and Suppliers Face Crisis

Factory workers at Nissan, Honda, and Bosch faced reduced hours and job insecurity as production cuts cascaded globally. Hella, Aumovio, ZF Group, and JABIL reported disruptions due to facility shutdowns.

Some suppliers purchased chips through Chinese entities using yuan payments. The crisis lasted from September through mid-November when China allowed exports to resume following a Trump-Xi meeting in Busan on October 30.

Political Intervention and Reversal

The Dutch emergency order under the Goods Availability Act aimed to protect technology from Wingtech. However, it inadvertently gave China leverage over production.

China retaliated against its export controls. The U.S. extended export restrictions on September 29. By mid-November, the Netherlands reversed course, suspending intervention to allow limited exports after China eased restrictions following the Trump-Xi summit.

Financial Scale and Industry-Wide Losses

Honda’s documented loss: ¥150 billion ($969 million). Bosch’s annual exposure: €200 million ($231 million). Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, Nissan, and Stellantis all suffered significant disruptions.

Industry-wide losses likely exceeded $2–5 billion had the crisis continued cascading. Individual chips cost fractions of a penny, yet production disruption was severe, highlighting the scale paradox in automotive supply chains.

Why Can’t Automakers Just Swap Chips?

Nexperia chips are soldered directly into power modules in hundreds of vehicle models. While competing chips may appear identical, they perform differently in vehicles, requiring extensive testing and regulatory approval—sometimes up to one year.

There are no quick fixes in replacing automotive semiconductors. This constraint forced automakers to seek emergency Chinese exports rather than invest 12 months in alternative sourcing.

Just-in-Time Inventory Fails Again

The crisis reignited debates on globalization and supply chains. The industry vowed “never again” after the 2020–2021 chip shortage, yet repeated the same mistakes by maintaining just-in-time inventory with no geopolitical buffer.

Some argued for reshoring production; others cited the environmental costs of stockpiles. Electric vehicles compound vulnerability, requiring more semiconductors than conventional cars. The industry’s resilience promises proved hollow.

Consumer Adaptation and Market Shift

Consumers delayed purchases, explored used vehicles, and considered car-sharing and public transit as new car availability tightened. Dealership inventories shrank. Automakers enhanced online sales platforms and digital engagement.

Potential price increases and multi-month delivery delays would have materialized had the crisis extended beyond mid-November, directly impacting consumer purchasing power and vehicle market dynamics.

Toyota’s Hidden Advantage

While competitors scrambled, Toyota maintained its output by utilizing semiconductor stockpiles developed after the devastating 2011 Japan earthquake.

This disaster-driven business continuity planning insulated Toyota from crisis worst impacts. The industry’s cost-cutting just-in-time model failed twice in five years (2020–2021 COVID, 2025 Nexperia), yet only Toyota had prepared.

Competitors with diversified sourcing also weathered disruption better than single-source-dependent firms.

The Year-Long Fix: Persistent Vulnerability

Hella and suppliers estimate alternative chip testing and regulatory approval could take up to one year—meaning vulnerability persists throughout 2026.

Nissan executives warned of “continuing risk for this year.” Consumers should monitor dealership inventories before major purchases.

The crisis exposed that despite 2020–2021 vows, most automakers remain unprepared for geopolitical disruption of commodity components.

Crisis Paused, Not Solved

The September–November 2025 crisis is paused, not resolved. The Netherlands reversed its intervention on November 19; China allowed limited exports, but underlying vulnerabilities persist.

Nexperia resumed sales with yuan payment requirements; wafer supplies remain unsettled; structural tensions between Dutch headquarters and Chinese ownership continue.

“No one prepared for geopolitical disruption, and they’re still not prepared,” said Ambrose Conroy, CEO of Seraph Consulting. Similar crises are inevitable without fundamental restructuring of the supply chain.

Sources:

Automotive Logistics, Nov 2025

Z2Data, Nov 2025

Reuters, Nov 2025

Nexperia, Oct 2025

Seraph Consulting, Nov 2025

Focus2Move, Nov 2025