The U.S. operates just two icebreakers in the Arctic: USCGC Polar Star and USCGC Healy. Russia commands over 40 heavy icebreakers, while China has five as of 2024.

This 20-to-1 disadvantage against Russian forces forced American military planners to face a harsh reality: America cannot match rivals who seek power in the frozen waters.

The gap grows wider as Arctic temperatures rise and competition intensifies across the north.

The Unprecedented Push

Between July and September 2025, a remarkable event occurred in Arctic waters near Alaska. Multiple Chinese research and military vessels arrived in U.S. waters simultaneously.

The Department of Homeland Security described this as “unprecedented in numbers,” highlighting how Beijing transitioned from rare visits to a constant, organized presence. U.S. Coast Guard commanders deployed cutters to track five Chinese vessels in claimed American waters.

The sudden surge left many experts wondering if America could protect Arctic interests.

Arctic Renaissance

The Arctic was once a frozen region with little strategic value. Cold War submarines occasionally came under ice, but ships rarely did. Climate change changed everything: melting ice opens shipping routes that cut 40 percent off Asia-Europe trips, and vast mineral deposits become reachable.

China referred to itself as a “near-Arctic” power in 2018, shocking Western leaders. Russia has already led Arctic action through the construction of icebreakers and military investment. By 2024, Beijing moved from words to real operations.

The Alliance Hardens

China and Russia moved from loose teamwork to a formal partnership in 2024. Both nations established a working group to develop the Northern Sea Route and jointly extract resources.

This signaled their intent to control Arctic trade and security. In July 2024, Chinese and Russian military planes flew their first-ever joint patrol near Alaska, coming within 200 miles of the U.S. coast.

These actions reflected deeper military ties and shared interest in reducing American Arctic influence.

The Breakthrough Moment

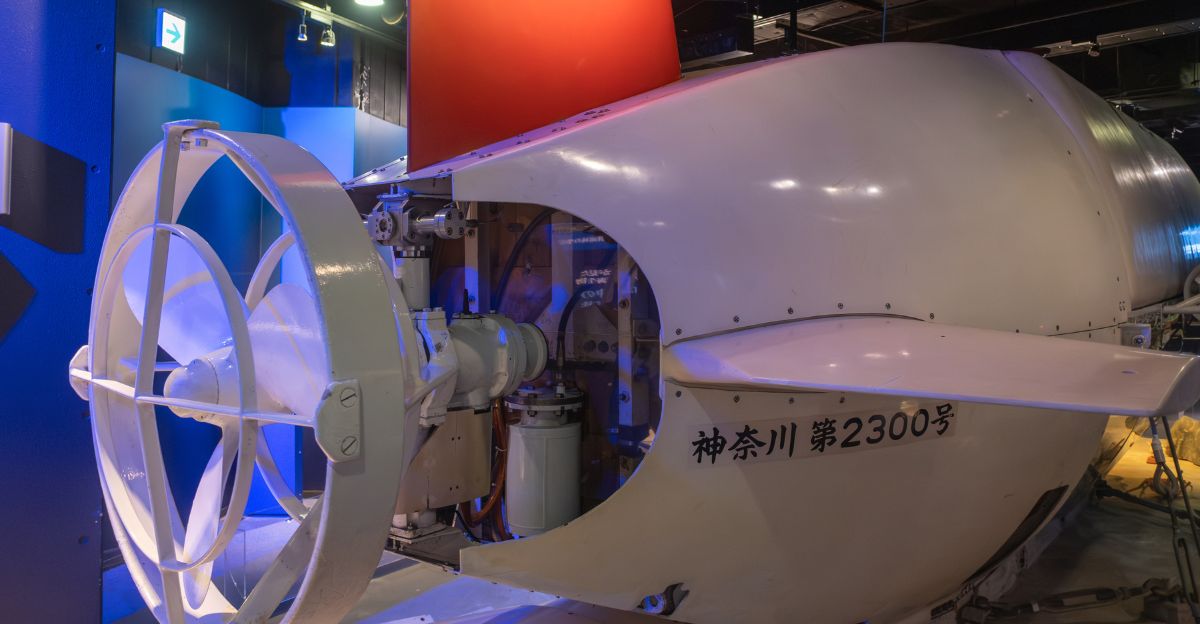

On August 6, 2025, China’s manned research submersible Jiaolong resurfaced in the Chukchi Sea, about 186 miles northwest of Alaska.

This was not routine. Jiaolong became the first Chinese crewed vessel to dive under Arctic pack ice—a significant technical achievement that showcases Beijing’s growing Arctic presence. The submersible, run from mothership Shen Hai Yi Hao, descended to study the seafloor and gather geological data.

Western experts noted immediately that this location put Chinese operations at distances military planners call strategically important.

Alaska’s Exposed Frontier

Remote Alaskan Arctic towns face direct exposure to growing Chinese and Russian activity. Utqiagvik, America’s northernmost city, sits just 143 miles south of where Chinese research ships now operate regularly.

Barrow, Prudhoe Bay, and other settlements lack enough Coast Guard help or emergency response. On August 31, 2025, Chinese research vessel Zhong Shan Da Xue Ji Di came within 143 miles of Utqiagvik.

The U.S. Coast Guard rushed to respond, but the Chinese ship finished its work first. Local leaders were concerned about outside monitoring and potential threats to critical systems.

The Monitoring Dilemma

Coast Guard leaders admitted the challenge of tracking Chinese activity. With only two working icebreakers for the entire Arctic, the service cannot watch continuously.

A Coast Guard official said in September 2025: “Multiple vessels operating at once creates challenges we’ve never faced.” The service deployed USCGC Healy, USCGC Waesche, and the upcoming USCGC Storis to respond, but these ships cannot be everywhere.

Beijing understood this gap: five coordinated vessels meant some would escape American observation. Alaska-based Navy and Coast Guard personnel felt frustrated by limited resources.

The Submersible Dimension

Jiaolong’s success opened new Arctic competition angles. The submersible reaches depths of 23,000 feet, allowing it to explore the Gakkel Ridge and features that surface ships cannot reach.

A second Chinese submersible, Fendouzhe, made 43 Arctic dives in summer 2025, reaching 17,322 feet. Together, both vessels completed nearly 50 dives under Arctic ice—more than any non-Russian nation had done.

These operations gathered seafloor maps, rock samples, and images that could guide future resource extraction or military moves. The U.S. has no equivalent research submersibles, and it relies on foreign assistance for polar science.

The DHS Warning Crystallizes

In November 2024, the Department of Homeland Security issued a formal warning: Chinese military and research ships operated in “unprecedented numbers” near Alaska. The warning came with the Icebreaker Collaboration Effort (ICE) Pact between the U.S., Canada, and Finland.

It named Beijing’s Arctic strategy as a homeland security threat. The DHS report noted Chinese vessels spent “extensive time” in American extended continental shelf waters and completed “nearly four dozen” submersible dives.

This warning made Arctic competition a domestic security issue, triggering budget talks and prompting the Trump Administration to accelerate icebreaker purchases and Arctic defense plans.

The Real Vulnerability: Data Gaps

While attention focused on the presence of Chinese ships, a bigger threat emerged: China’s Arctic information collection efforts. Through five icebreakers, two research submersibles, and dozens of surveys, Beijing gathered detailed seafloor maps, temperature readings, ocean currents, and biological samples from Arctic regions where America has little recent data.

This information edge could matter greatly: optimizing submarine routes under ice, finding resource sites, predicting environmental shifts, or finding underwater targets.

American oceanographers warned that China would hold better Arctic datasets than the U.S. by 2026—a dramatic reversal that would affect strategy for decades.

U.S. Officials Express Frustration

Behind closed doors, American military and intelligence leaders expressed anger over years of delayed Arctic spending. A senior Navy strategist, speaking anonymously to the Alaska Dispatch News in September 2025, stated: “We’ve warned about Arctic power for a decade.

China built five icebreakers then. We built zero.” Officials fumed that Arctic Command and NORAD warnings did not create a budget priority until China’s deployment forced action.

Congress inquired why America’s icebreaker fleet had shrunk instead of growing over the past decade. Leaders admitted reacting after Chinese vessels arrived, rather than planning ahead to stop them.

The ICE Pact Acceleration

The Trump Administration fast-tracked the ICE Pact after the summer 2025 Chinese deployment. The three-nation deal with Canada and Finland committed $500 million toward icebreaker building and Arctic structures.

Finland, with advanced polar technology and shipbuilding skills, became the main builder of new U.S. icebreakers. The first new polar icebreaker under the ICE Pact was launched in 2028, with additional ships following every two years.

The newly commissioned USCGC Storis, delayed by budget constraints, entered service in August 2025. This brought the U.S. operational icebreakers to three, still far below the numbers of Russia and China. Officials deemed the speed necessary but insufficient without Congress maintaining steady funding.

The NATO Response Complicates Dynamics

NATO members, primarily Iceland and the Nordic nations, responded to Arctic tensions by increasing submarine-hunting patrols and deploying anti-submarine warfare assets to the GIUK Gap and surrounding Arctic waters.

The annual NATO exercise Dynamic Mongoose expanded in 2025, with more nations and a wider operating area. NATO also restructured Arctic command, putting Nordic nations under expanded Atlantic and Arctic commands.

These moves aimed to boost teamwork and coverage but risked escalating tensions with Russia and China, who viewed NATO’s Arctic expansion as hostile. Since Russia and China coordinate their Arctic activities, NATO’s actions against one nation might trigger a response from both, making the region more complex and dangerous.

China’s Long Game Reshapes Expectations

For Beijing, 2025 showed capability, not maximum effort. Chinese planners said Arctic operations are expected to grow annually through the 2020s, with the addition of more icebreakers, submersibles, and research ships.

The Northern Sea Route—an Arctic shipping corridor—stays central to China’s Belt and Road plan. Less ice and longer open seasons mean that year-round Arctic work becomes profitable by 2030, making current spending a smart long-term investment.

Western experts debated whether China focuses on science, business, or military goals—but agreed that Beijing combines all three, making old definitions obsolete. American strategists worried: China has built Arctic power through 20-year plans, while America responds to yearly budget fights.

Who Controls the North?

As Arctic ice melts faster than most climate models predicted, one question reshapes global power: Which nation will control polar trade, security, and resources? Summer 2025 suggested an answer that surprised few but worried many policymakers: not the United States.

China and Russia demonstrated their power, teamwork, and willingness to lead Arctic action—while America showed its limits, reactive moves, and scarce resources. Whether this changes depends on the choices made in the next five years.

If America maintains strong Arctic investment through politics and competition, American power is restored. If trends continue, the Arctic’s shift from an unreachable frontier to a contested zone will occur under Beijing and Moscow’s rules. The ice melts. The question is whether America shows up.