On June 1, 2024, China’s Chang’e-6 spacecraft achieved a historic landing in the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin—a region long shrouded in mystery and scientific intrigue. This mission marked the first time any spacecraft had touched down in this ancient, shadowed expanse, opening a new era in lunar exploration. The South Pole-Aitken Basin, with its extreme age and depth, has preserved clues about the Moon’s origins and evolution that have eluded researchers for decades.

Unraveling a Lunar Mystery

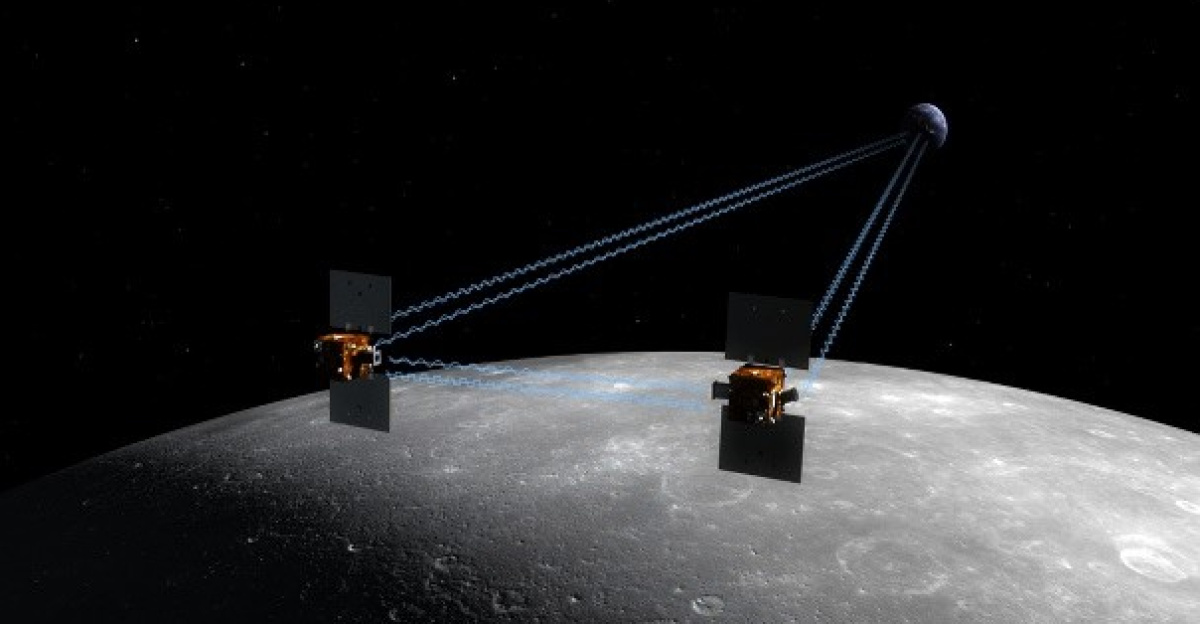

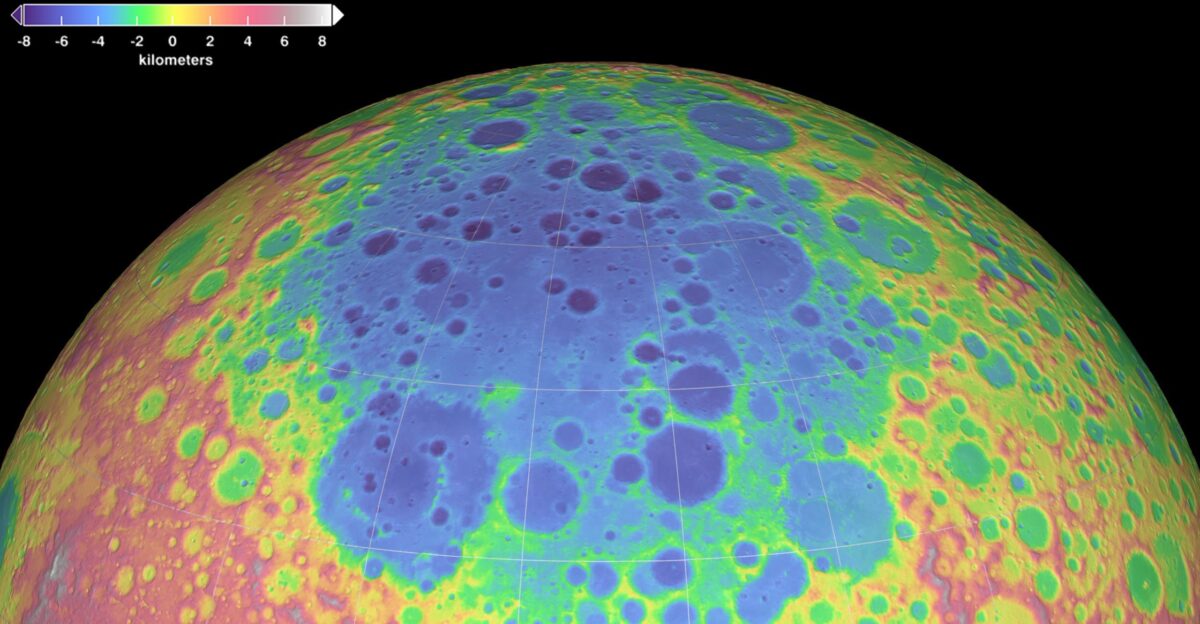

The South Pole-Aitken Basin is not only the largest confirmed impact structure on the Moon but also the site of a puzzling gravitational anomaly. Detected in 2019 by NASA’s GRAIL mission, this anomaly is a buried mass estimated to be five times heavier than Hawaii’s Big Island, located about 300 kilometers beneath the surface. Its immense gravitational pull subtly alters the orbits of passing satellites, raising questions about its origin—whether it is the remnant core of a colossal asteroid or a vast deposit of ancient magma.

Formed 4.25 billion years ago by a massive impact, the basin stretches 2,500 kilometers across and plunges 8 kilometers deep. The force of its creation excavated material from the Moon’s interior, offering scientists a rare window into the planet’s early history. For years, the basin’s unique geology and the unexplained gravitational anomaly have made it a prime target for international lunar research.

China’s Expanding Lunar Ambitions

China’s Chang’e lunar program has advanced steadily since its inception in 2007, with each mission building on the last. The 2020 Chang’e-5 mission returned samples from the Moon’s near side, but Chang’e-6 set its sights on the far side’s south pole—a region never before sampled by any nation. This bold move aimed to answer fundamental questions about the Moon’s composition and the forces that shaped it.

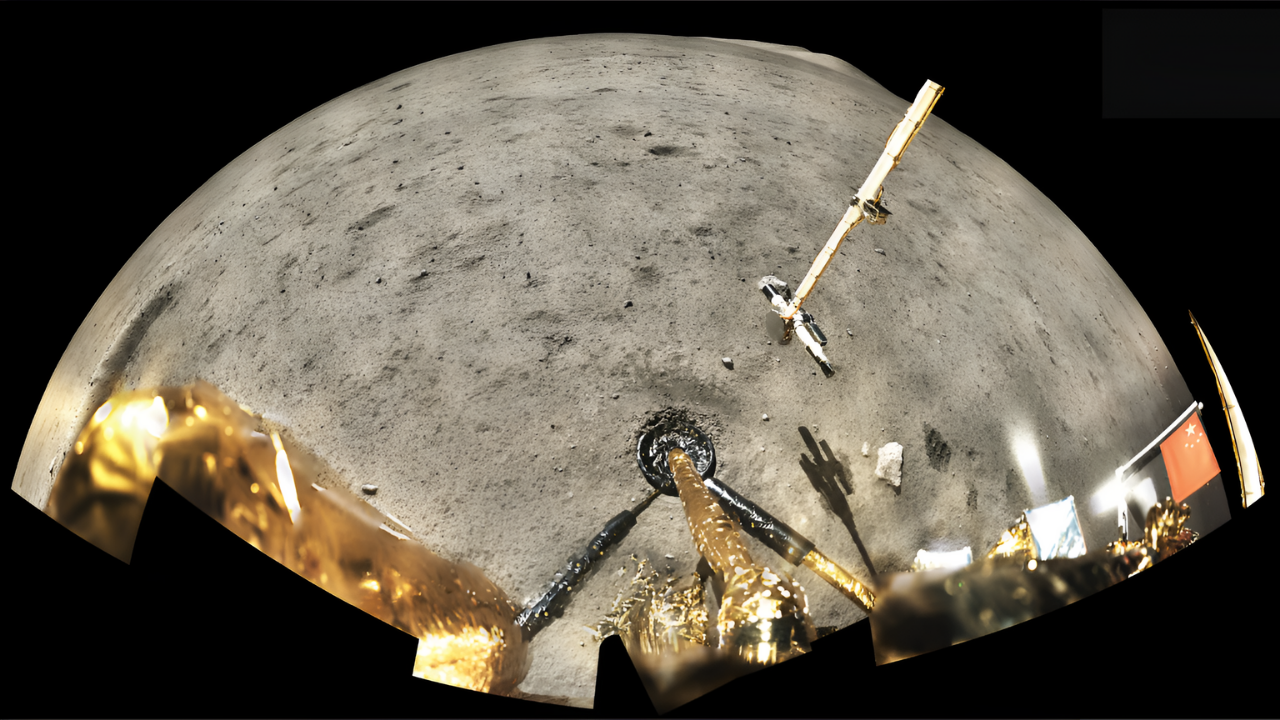

Landing in the Apollo crater within the South Pole-Aitken Basin, Chang’e-6 deployed robotic scoops and drills to collect nearly two kilograms of lunar soil and rock over a 48-hour period. The samples were then launched back to Earth, landing in Inner Mongolia on June 25, 2024. These are the first physical samples ever retrieved from this remote and scientifically significant region.

Breakthrough Discoveries in Lunar Geology

Upon return, Chinese laboratories began analyzing the Chang’e-6 samples using advanced spectroscopic and microscopic techniques. The focus was on identifying mineral compositions, isotopic signatures, and magnetic properties that could reveal the Moon’s geological history. In November 2025, researchers made a startling discovery: the presence of crystalline hematite and maghemite—forms of oxidized iron commonly known as rust.

This finding challenged decades of assumptions. The Moon, lacking both water and atmosphere, was believed to be chemically reduced, making the formation of rust-like minerals seemingly impossible. The discovery forced scientists to reconsider how such minerals could form in an airless environment. After extensive analysis, a new theory emerged: asteroid impacts may briefly create oxygen-rich conditions, allowing these minerals to crystallize before the environment returns to its usual state.

Implications for Science and Exploration

The detection of hematite and maghemite in the Chang’e-6 samples suggests that the Moon’s surface chemistry is more dynamic than previously thought. These minerals, with their unique magnetic properties, may help explain localized magnetic anomalies detected across the South Pole-Aitken Basin. While the deep gravitational anomaly remains unexplained, the surface findings have opened new avenues for research into the Moon’s magnetic and geological history.

The presence of oxidized iron also has practical implications. Researchers are exploring how these minerals could support future lunar construction, providing raw materials for building, oxygen production, or even water extraction. As China aims to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030, understanding the Moon’s mineral resources is becoming increasingly important for sustainable exploration.

Global Competition and Legal Uncertainty

China’s success with Chang’e-6 has intensified international interest in the Moon’s south pole. NASA and the European Space Agency have expressed interest in collaboration, while the U.S. Artemis program has accelerated its plans to establish a lunar base in the 2030s. The discovery of potential water ice in the region’s shadowed craters adds to the strategic value, as these resources could support long-term human presence.

However, the race for lunar resources is unfolding amid legal ambiguity. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prohibits national appropriation of celestial bodies, but it leaves questions about resource extraction unresolved. As more nations develop lunar capabilities, the need for clear international agreements on resource utilization is becoming urgent.

Looking Ahead

The Chang’e-6 mission has not only advanced scientific understanding of the Moon but also reshaped the geopolitical landscape of space exploration. With China planning further missions, including the Chang’e-7 rover to search for water ice, the Moon’s south pole is set to remain a focal point for discovery and competition. As scientists analyze the new samples and nations vie for lunar resources, the secrets of the Moon’s ancient past continue to shape the future of exploration.