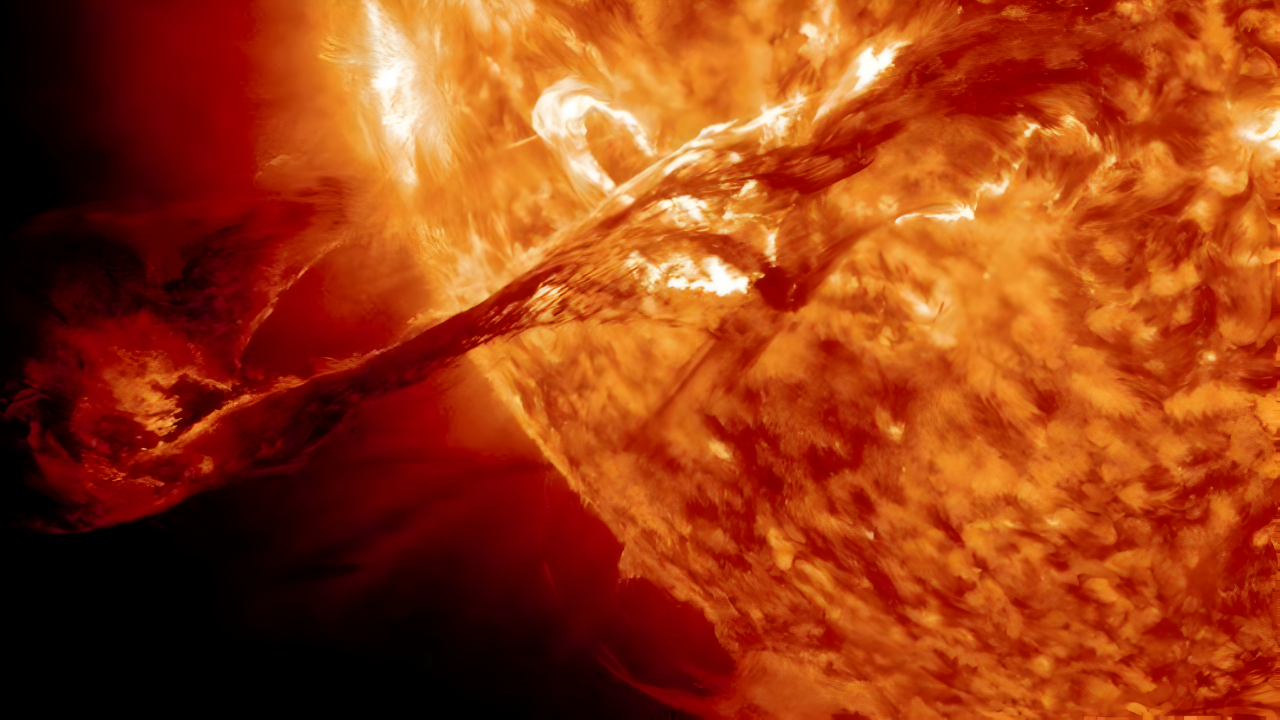

The Sun unleashed an unusually intense eruption on December 6, 2025, sending a blast of charged particles hurtling toward Earth and setting off a global readiness effort across aviation, satellite operators, and power-grid managers. Detectors registered an M8-class solar flare at 20:39 UTC, followed by a powerful “cannibal” coronal mass ejection (CME) expected to drive a G3-Strong geomagnetic storm around December 9. Scientists say the event is unlikely to be catastrophic but could cause short-lived disruptions to communications, navigation systems, and some electrical infrastructure, even as it creates rare aurora displays far beyond their usual range.

A rare cannibal CME and a strong geomagnetic forecast

This solar eruption stands out not only for its size but for the structure of the CME driving toward Earth. A “cannibal” CME occurs when multiple eruptions from the Sun merge, with a faster-moving ejection overtaking one or more earlier ones. As the CMEs combine, their magnetic fields and energy can reinforce each other, creating a more complex and potentially stronger impact when they encounter Earth’s magnetic shield.

In this case, forecasters classified the flare as M8-class, near the top of the medium-strength M scale but still below the most extreme X-class events. Even so, the merged CME is expected to carry a more intense and better-organized magnetic field than many single eruptions. That configuration, especially if oriented southward when it reaches Earth, can couple efficiently with the planet’s magnetosphere and drive a G3-Strong storm on NOAA’s five-level scale. A storm at this level can cause intermittent navigation and radio issues, increased drag on satellites in low-Earth orbit, and stronger-than-normal currents in power lines at higher latitudes.

Communications and navigation feel the first effects

The first signs of trouble arrived quickly. Within hours of the flare, high-frequency radio users in the Pacific region reported a 15–20 minute loss of communication on December 6. Shortwave signals below about 20 MHz were affected as the flare’s radiation temporarily disturbed the upper atmosphere, disrupting the paths that radio waves normally follow over long distances.

As the CME itself approaches, NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center has warned of additional radio and GPS irregularities, particularly for systems that rely on precise timing and stable ionospheric conditions. Aviation is a central concern: long-distance flights, especially those crossing oceans or flying over polar regions where ground-based alternatives are sparse, depend heavily on high-frequency radio and satellite navigation. Airlines and air traffic managers are preparing for possible further blackouts, with contingency plans that include rerouting some high-latitude flights and using alternative communication channels where available.

For everyday users, the most noticeable effects, if they occur, are likely to be brief glitches in GPS accuracy and occasional satellite-based communication delays. Experts emphasize that these impacts would be temporary but may cause delays or rerouting in transportation networks and some inconvenience in navigation-dependent services.

Satellites, power grids, and aviation on alert

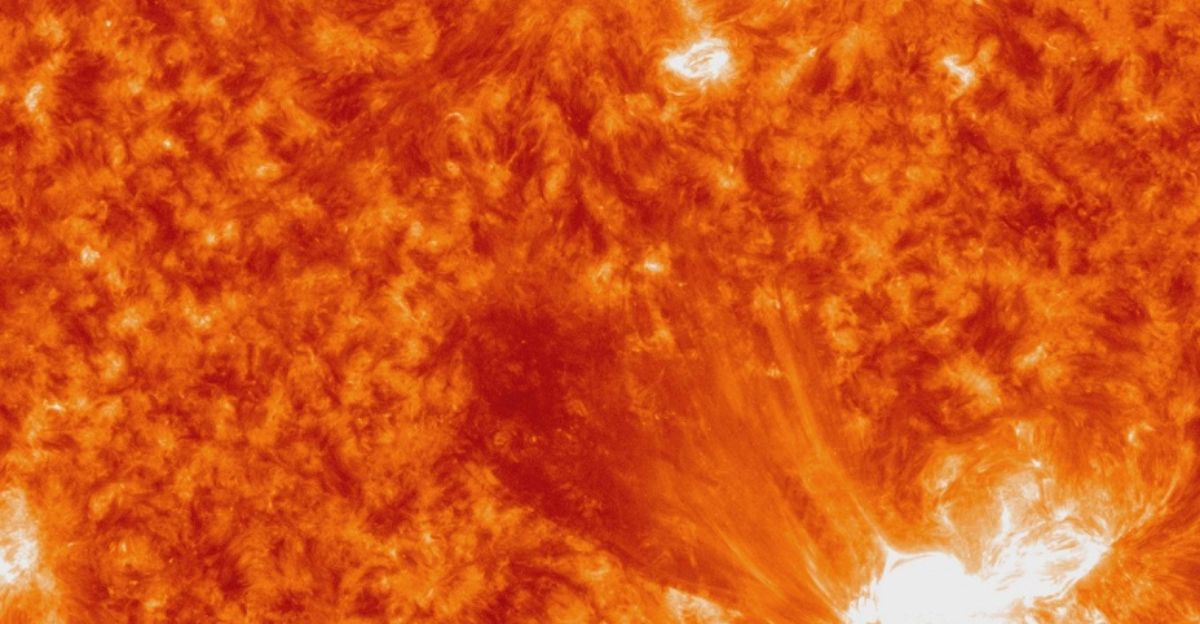

In orbit, operators of satellites are closely tracking space-weather forecasts. When geomagnetic storms intensify, energy deposited in the upper atmosphere causes it to expand slightly, increasing drag on spacecraft flying in low-Earth orbit. That drag can alter their paths and require more frequent adjustments to maintain altitude and orientation. Charged particles from the CME can also induce electrical anomalies in satellite electronics, leading to resets or momentary outages that control teams must correct.

On the ground, utilities in northern regions are preparing for geomagnetically induced currents—weak but widespread electrical currents that can flow through power lines and transformers when Earth’s magnetic field is strongly disturbed. These currents can heat components and, in extreme cases, damage high-voltage transformers. For a G3 storm, grid operators do not expect widespread failures but are ready to apply measures such as adjusting voltages and reconfiguring networks to keep any disturbances localized and short-lived.

Aviation authorities, meanwhile, are reviewing and updating procedures for operating through periods of degraded radio coverage. High-frequency radio links are vital for aircraft traveling over oceans and polar areas that lack continuous line-of-sight connections to ground stations. With disruptions already seen over the Pacific, airlines are on heightened watch for further communications issues as the main body of the CME interacts with Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field.

Brighter skies, modest economic risks, and public perception

While the storm brings operational challenges, it also delivers a spectacle. Forecasters expect auroras to be visible much farther south than usual, potentially reaching U.S. states such as Oregon and parts of the Midwest and boosting interest in aurora-focused tourism. Communities that normally see only occasional displays may experience vivid, sustained lights as charged particles funnel along Earth’s magnetic field lines and collide with atmospheric gases.

Economically, a single G3 event is not expected to produce major, lasting damage. However, forecasters and regulators note that repeated storms during the ongoing peak of Solar Cycle 25 can cumulatively raise costs for sectors that rely on satellites, GPS, and radio. Industries such as logistics, telecommunications, and agriculture, which depend on precise positioning and real-time data, may see higher operational expenses from workarounds, insurance claims, and contingency measures when storms become frequent.

For the public, reaction spans fascination and anxiety. Spectacular aurora images tend to dominate public attention, but social media also amplifies concerns about widespread blackouts or long-term infrastructure failure. Specialists in space weather underline that while risks are real and require planning, the current storm falls within a range that modern systems are designed to withstand, especially with advance warning and established protective procedures.

Looking to the peak of Solar Cycle 25

NASA, NOAA, and partner agencies are using this event as both a test and a learning opportunity. Through the Space Weather Prediction Center, they are issuing real-time alerts to power-grid operators, airlines, satellite companies, and emergency managers, while comparing forecasts with actual impacts to refine their models. The aim is to improve timing and intensity predictions, which are crucial for deciding when to power down sensitive equipment, adjust satellite orbits, or alter flight routes.

Scientists also stress that while solar storms can strongly affect technology and infrastructure over short periods, they are distinct from longer-term climate influences. Events like this underline society’s dependence on space-based systems and highlight the importance of continued investment in monitoring satellites, ground sensors, and forecasting capability.

As Solar Cycle 25 moves toward its maximum, more frequent and occasionally stronger storms are expected. This latest M8-class flare and cannibal CME serve as a reminder that the Sun’s changing mood can ripple quickly through modern life—from quiet shifts in satellite orbits to bright curtains of light in night skies far from the Arctic. The experience gained in managing this storm will feed directly into preparations for the next, as agencies, industries, and communities adapt to an era of heightened solar activity.

Sources

NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center G3 Geomagnetic Storm Watch, December 6, 2025; SWPC solar flare classification and radio blackout guidance

NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory Solar Cycle 25 reports; Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) coronal mass ejection monitoring

SpaceWeatherLive M8.1 solar flare bulletin, December 7, 2025; Royal Observatory of Belgium Solar Influences Data Analysis Center

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) geomagnetically induced currents power grid impact analysis; NOAA electric power transmission space weather effects documentation