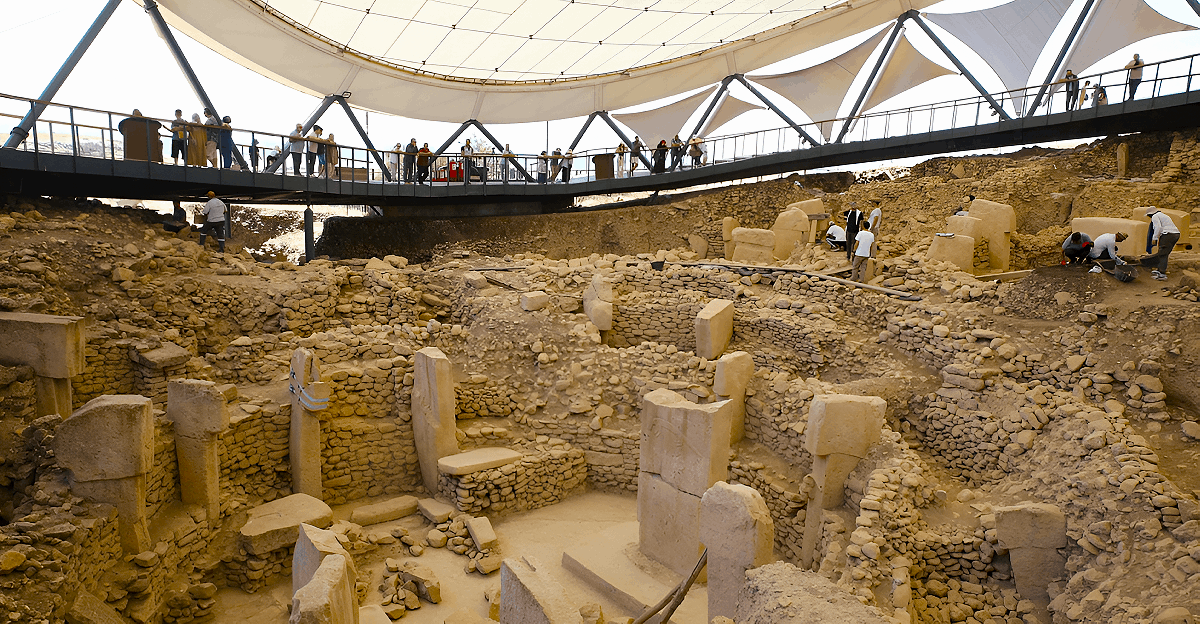

At Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, researchers have found old carvings that could be the world’s oldest solar calendar, much older than any other known calendar.

This ancient site, built about 12,000 years ago, reveals new surprises about early humans. Large stone pillars carved with V-shaped symbols might show how people tracked the days of the year.

Klaus Schmidt first studied the site in 1995 and is now known as one of the earliest massive monuments ever built.

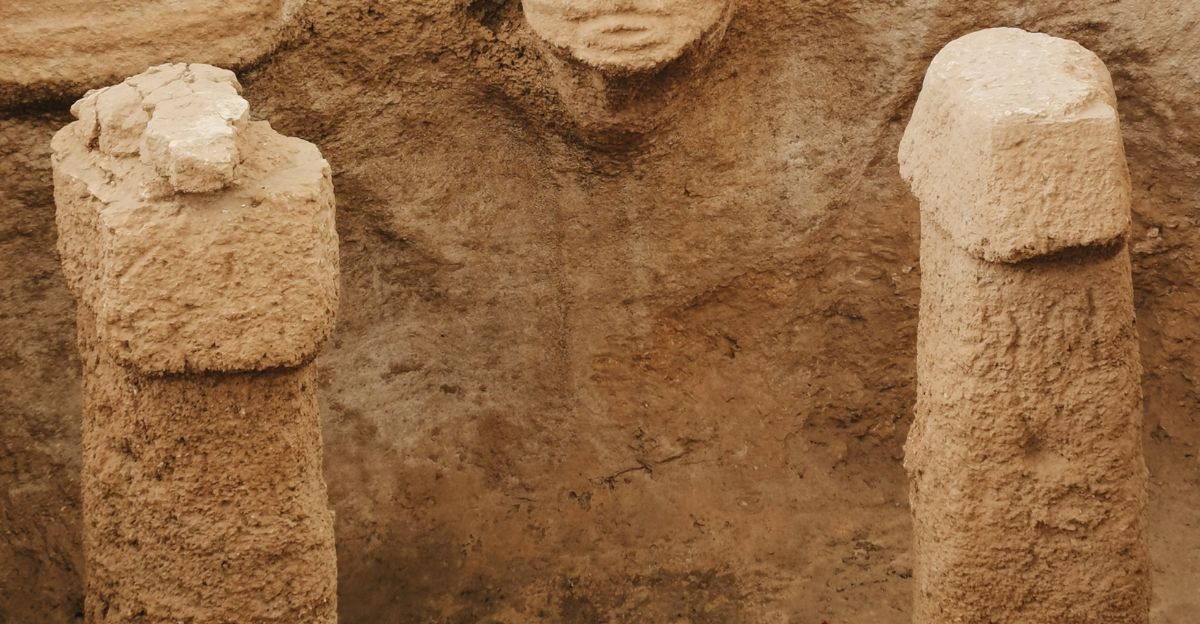

Calendar Symbols

Martin Sweatman from the University of Edinburgh believes these V-shaped carvings are more than decoration. He says, “We can interpret these V-shaped symbols and little box symbols on the pillar to be counting the days of the year like a calendar.”

He counted 365 Vs on one stone—one for each day of the solar year. The marks form a detailed time system based on the moon’s phases and the sun’s path, which experts call a lunisolar calendar.

A special V-mark on a carved bird shows the summer solstice, and similar marks appear on other statues that could be sky gods.

Archaeological Context

Göbekli Tepe was built before people widely farmed, when hunter-gatherers still dominated the region. This place comprises circles of giant limestone pillars, some weighing up to 60 tons, and all moved there without wheels or metal.

Experts believe only about 5% of the site has been dug up, but they’ve already found at least 20 different stone circles. How the monuments are laid out shows that ancient builders could do complex math, and pictures carved into the stones include all kinds of wild animals in the area.

Research Background

Martin Sweatman has been studying these symbols for years, especially after finding that many are connected to the stars and planets. For example, his work on the “Vulture Stone” suggests that the people at Göbekli Tepe tracked comets and the sky in great detail.

Sweatman says, “It tells us so much about what the people back then were capable of if we’re correct. It tells us that they were good naked eye astronomers, much more advanced in their knowledge of astronomy than generally given credit for.”

These studies mix math, archaeology, and astronomy to find real patterns.

The Calendar Discovery

According to Sweatman, the builders used the V-shaped symbols to create a 365-day calendar, even marking 12 months and the extra 11 days the sun takes to catch up with the moon yearly.

He explains, “Since both the moon’s and the sun’s cycles are depicted, the carvings could represent the world’s earliest so-called lunisolar calendar, based on the phases of the moon and the position of the sun – pre-dating other known calendars of this type by many millennia.”

The special V-symbols that show important events suggest ancient people tracked the sky in detail to help with farming, religion, and social events.

Comet Connection

Some scientists, including Sweatman, think the calendar might also be a record of a massive comet impact about 13,000 years ago.

He says, “The detailed engravings at Göbekli Tepe narrate the event and record when fragments from a comet collided with Earth approximately 13,000 years ago.”

This disaster may have caused significant climate changes and driven early people to settle down and start farming. Pillars at the site may even show pictures of the deadly meteor shower itself.

Regional Impact

Sweatman also suggests the comet disaster pushed people living at Göbekli Tepe to watch the skies closely and change how they lived.

He notes, “It appears the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were keen observers of the sky, which is to be expected given their world had been devastated by a comet strike. This event might have triggered civilisation by initiating a new religion and motivating agricultural developments to cope with the cold climate.

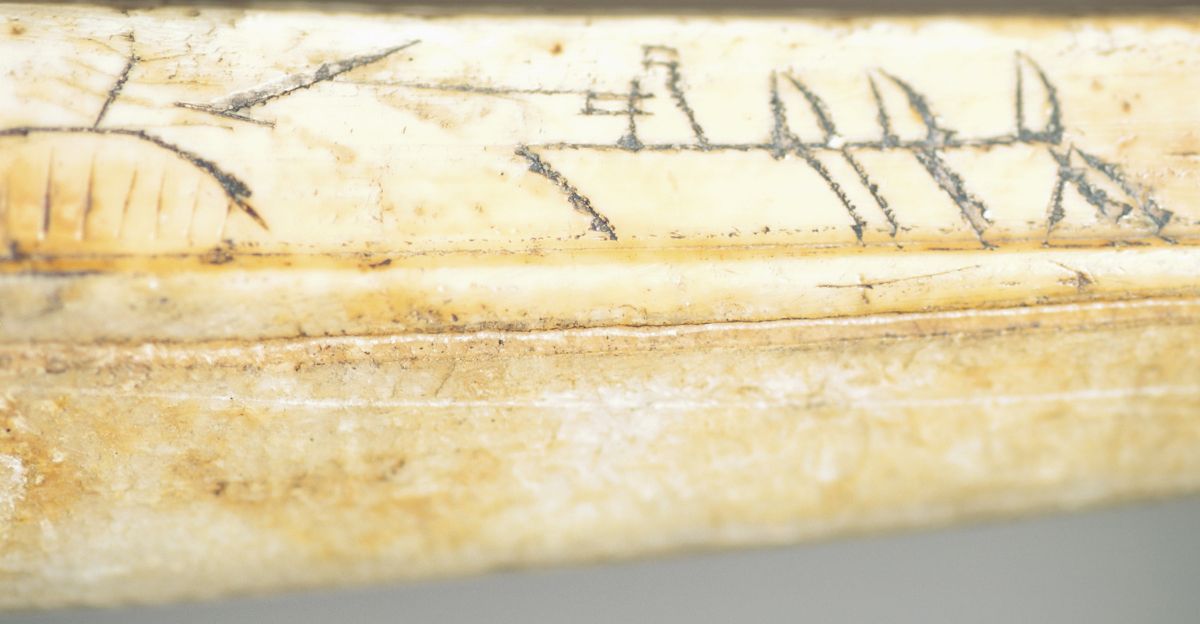

Possibly, their attempts to record what they saw are the first steps towards the development of writing millennia later.” The move from wandering to settled villages happened in this region soon after the impact.

Scientific Methodology

Sweatman’s research uses math to show how unlikely these marks happened by chance, saying the odds are as low as one in 380 million.

This careful counting and pattern-checking help back up the theory. Other experts are now looking for similar patterns at Göbekli Tepe’s many monuments.

Sweatman says, “If accurate, it could represent the first and oldest known example of a lunisolar calendar that notes the phases of the moon and the position of the sun in the sky.”

Broader Implications

If the research is correct, ancient people were highly skilled at observing and recording the stars and seasons, long before writing was invented.

“It tells us that they were good naked eye astronomers, much more advanced in their knowledge of astronomy than generally given credit for,” says Sweatman.

This could mean even more early science is waiting to be rediscovered at other ancient sites worldwide.

Alternative Calendars

Even though Göbekli Tepe may be the oldest, other old sites also show people watching the sun and stars.

Nabta Playa in Egypt (from about 7,000 years ago) has stones marking the summer sunrise; Germany’s Goseck circle (around 4900 BCE) acted as a stone observatory, and ancient Egyptian calendars followed the sun by 3,100 BCE.

But Göbekli Tepe’s system seems to go back further than all these examples.

Scholarly Criticism

Not everyone agrees with Sweatman’s calendar idea. Some archaeologists think the V symbols are just art, not a calendar.

Sweatman admits, “Archaeologists at the site did not receive the idea well. To my knowledge, archaeoastronomy is not taught as a component of any archaeology degree. Consequently, some archaeologists don’t even understand the difference between astronomy and astrology.”

Some critics say that math fitting into ancient art doesn’t always work because people might have had other reasons for their carvings.

Excavation History

Klaus Schmidt’s discovery in the 1990s changed our view of early human culture. Schmidt recognized the site’s importance when he realized mysterious “tombstones” were ancient stone circles.

With his German and Turkish teams, he found more and more rings and pillars, showing how advanced these early builders were.

Ongoing digs keep finding new clues about how the site was used and why it was built.

Construction Mysteries

Building Göbekli Tepe required knowledge and teamwork we didn’t expect from early humans.

Workers used stone hammers to carve out fifty-ton pillars, moved them across dirt without wheels, and set them upright with precision.

The careful placement of pillars in circles shows they could plan and measure accurately—even though they didn’t have writing or modern math.

Cultural Context

Göbekli Tepe was built when people started experimenting with farming and animal herding in the Fertile Crescent.

Experts think the site was a place for religious ceremonies and bringing groups together.

The many animal carvings reflect life in a world full of wild animals, just before farming changed the land forever.

Future Research

With only a small part of the site uncovered, experts think even more ancient calendars or sky maps could be found.

New scanning methods and nearby digs at places like Karahan Tepe may reveal how the people of the region all kept track of the heavens.

Each new find could change what we know about early science.

Modern Investigations

Modern technology, like 3D scanning, now lets scientists explore Göbekli Tepe’s carvings in fine detail.

Scans can uncover marks hidden by shadows or wear, letting us see details missed before.

Working at more sites nearby helps researchers compare findings and see the bigger picture of the region’s early cultures.

Archaeological Networks

Göbekli Tepe’s discovery made researchers look for similar sites across Turkey and the surrounding region.

Now, they find related stone circles and patterns, showing that people shared ideas and knowledge over large distances instead of just learning everything in one place.

The more archaeologists look, the clearer the network of early innovation becomes.

Public Reception

People everywhere are fascinated by the idea of the world’s oldest calendar, and social media has helped make Göbekli Tepe famous.

While some stories about the site are exaggerated online, schools and museums now include it when teaching about history, showing how important it is for understanding what ancient humans could do.

Historical Precedent

Debates about Göbekli Tepe are part of a tradition—big discoveries often challenge what we thought was possible.Ancient cave art and the Antikythera mechanism were found, both showing that people were smarter and more scientific than experts had believed.

Göbekli Tepe may become a new example of how the past can surprise us.

Challenging Assumptions

Whether or not Göbekli Tepe’s carvings really make up the first calendar, the site proves that early humans understood astronomy and math much more clearly than once thought.

Sweatman’s research offers strong hints that they recorded sky cycles on stone. These findings remind us that with new technology and open minds, we can keep unlocking ancient knowledge and rewriting the story of civilization.