The vast ring of water encircling Antarctica holds more heat than any other part of the global ocean, quietly shaping the planet’s climate and potentially its future. Since the Industrial Revolution, the Southern Ocean has absorbed over 90% of the excess heat trapped by human-caused greenhouse gases, accounting for roughly 80% of total ocean heat uptake worldwide. That immense reservoir has helped limit surface warming so far. But new research suggests that under some successful climate scenarios—where emissions fall and carbon is pulled from the atmosphere—that stored warmth could return to the surface in a burst lasting more than a century.

Hidden Risk in a “Best-Case” Future

Climate simulations highlight a paradox. If governments cut emissions sharply and adopt large-scale carbon removal, global temperatures would gradually decline. Yet the same models show that this cooling could destabilize the Southern Ocean’s layered structure, triggering an abrupt release of stored heat back into the atmosphere. In this scenario, the planet would experience a renewed warming of about 0.1–0.2 degrees Celsius per decade for around 100 years, comparable to today’s human-driven warming rate.

Scientists stress that this outcome is not guaranteed. It emerges under specific assumptions about how quickly carbon dioxide concentrations rise, then fall, and how the ocean responds. But the behavior appears consistently across different modeling approaches, enough that researchers around the world now treat it as a serious possibility that needs closer examination.

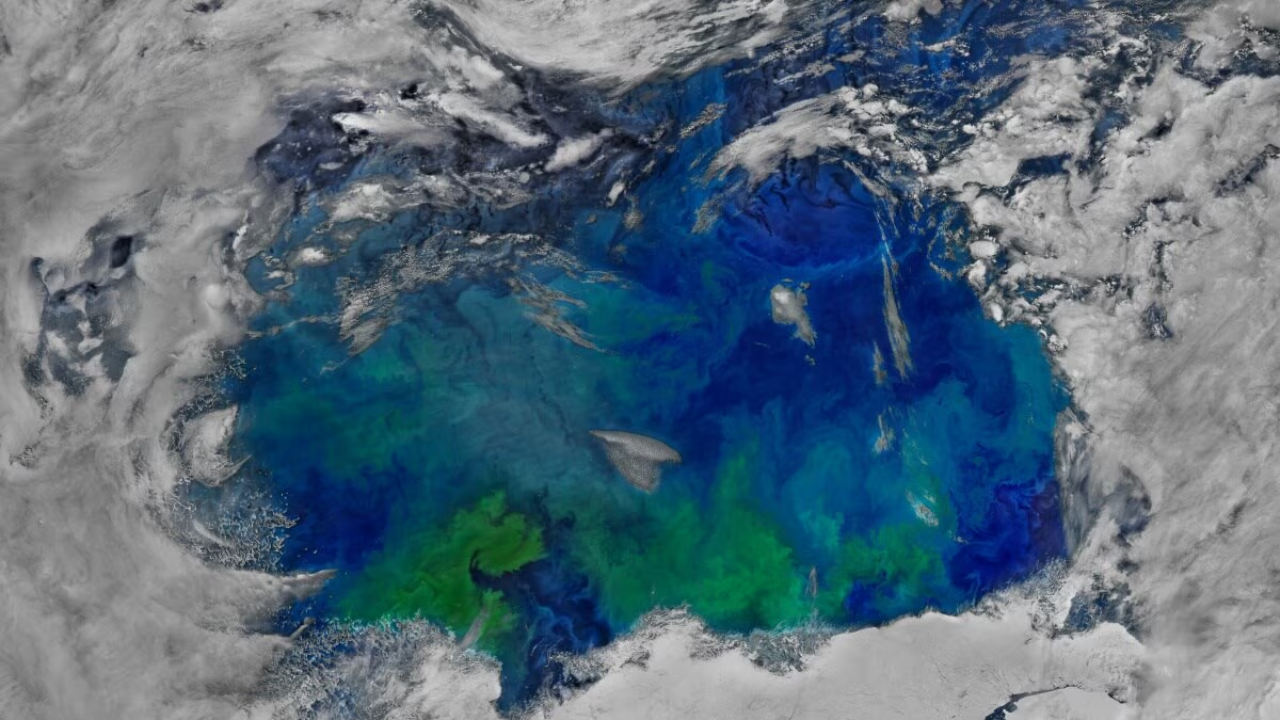

Why the Southern Ocean Became a Heat Reservoir

The Southern Ocean is unusually effective at soaking up heat because of its circulation patterns and cleaner skies. Powerful currents funnel relatively warm waters from lower latitudes toward Antarctica, while deep, cold waters upwell to the surface, where they can absorb solar energy and additional heat from the atmosphere. The Southern Hemisphere’s atmosphere also contains fewer industrial aerosols than the north, meaning less sunlight is reflected back to space and more reaches the water’s surface.

These physical and chemical conditions make the region a global heat sink. As fossil fuel use has pushed atmospheric carbon dioxide from about 280 parts per million before industrialization to over 420 parts per million today, that sink has grown. The more greenhouse gases accumulate, the more excess warmth the ocean must absorb. This creates a central dilemma: continuing high emissions increase the size of the underwater heat store, but reversing those emissions could eventually trigger its release.

Inside the Study and Its “Thermal Burp”

The warning about a century-long “thermal burp” comes from work led by scientists at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre in Germany and the University of Liverpool, published in AGU Advances in December 2025. The team used the University of Victoria climate model, an intermediate-complexity system that simulates the atmosphere’s energy and moisture balance, ocean circulation, sea ice, land ecosystems, and ocean chemistry over many centuries.

They examined a standard scenario in which atmospheric carbon dioxide gradually doubles over 70 years, then declines as net-negative emissions pull more CO₂ out of the air than human activities add. In the simulations, surface temperatures rise during the initial buildup, then cool as concentrations fall. Centuries into this cooling phase, however, the Southern Ocean’s water column becomes unstable.

According to study coauthor Svenja Frey, this instability occurs when cold, salty surface water overlies warm deep water that has become relatively light, making the vertical structure prone to sudden mixing. Once deep convection begins, heat from the ocean interior is transported upward and released to the atmosphere over more than 100 years. The models show that this thermal pulse does not carry a corresponding surge of CO₂ into the air, because much of the carbon remains chemically bound in seawater; the main impact is temperature, not greenhouse gas levels.

Global Stakes Around Antarctica

Any major change in the Southern Ocean reverberates worldwide. The waters around Antarctica help regulate Earth’s temperature, influence major ocean currents, and interact with ice sheets that hold enough frozen water to raise sea levels by many meters. A prolonged heat pulse from this region could accelerate melting of Antarctic ice, disrupting sea level projections and threatening coastal communities.

Warmer waters and altered circulation would also stress marine ecosystems that have evolved under stable, cold conditions. Fisheries could face shifts in species ranges and productivity. On land, the additional warming would interact with weather systems and climate zones already under pressure from today’s trends, creating new challenges for agriculture and infrastructure in multiple regions.

Unanswered Questions and Policy Choices

Researchers emphasize that the “burp” is a scenario, not a forecast. Climate scientist Kirsten Zickfeld notes there is still large uncertainty in how the Earth system responds when societies move into net-negative emissions and the planet begins to cool. Models have been tuned and tested mostly under warming conditions; far less work has explored the dynamics of large-scale cooling and long-term carbon removal.

Even so, the findings sharpen a policy tension. Net-negative emissions and carbon removal are widely seen as necessary if the world overshoots temperature limits such as 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius. Yet the same measures might, centuries later, help trigger an ocean-driven rewarming. The study’s authors argue this does not weaken the case for reducing emissions. Instead, they say the priority should be avoiding emissions in the first place, limiting the total heat stored in the ocean and the scale of future carbon removal needed.

The work also highlights gaps in today’s observing systems. Current monitoring focuses on tracking heat entering the ocean, not on detecting early signs that deep layers are becoming unstable. Expanding sensor networks, satellite measurements, and international observation programs in the Southern Ocean will be crucial for understanding whether the modeled behavior is beginning to unfold.

The timing of any such event, if it occurs at all, likely lies centuries ahead, beyond the lifetimes of people making decisions today. But the path to that future is being set now, as governments decide how quickly to cut fossil fuel use and how aggressively to pursue carbon removal. The Southern Ocean’s hidden heat raises a long-term question: whether a better understanding of this potential risk will change current climate strategies, or simply add urgency to efforts already underway to limit warming and improve knowledge of the planet’s most remote waters.

Sources Grist, November 2025

AGU Advances, December 2025

Live Science, November 2025

Eos (AGU), October 2025

Nature Climate Change, July 2024

IPCC National Academies Report, 2024

NOAA Ocean Heat Content, 2025