On a summer day in July 2025, UA Museums paleontologist Dr. John Friel was scanning the gravel bars of a Greene County creek when he stumbled on an unexpected prize.

Buried among the river pebbles, he found a duck-billed dinosaur’s tooth – an 84-million-year-old fossil that had lain unnoticed for millions of years.

News of this discovery immediately electrified Alabama’s scientific community.

Here, where ponds and streams often yield ancient shells and shark teeth, finding a dinosaur relic on a creek’s sandy bottom was truly a surprise.

Raising the Stakes

Typically, Alabama’s Cretaceous sediments are rich in marine fossils like ammonites and mosasaurs. But this tooth came from a land-dwelling hadrosaur, making it wildly unusual for the site.

In fact, Friel notes the creek cuts through sediment “formed roughly 84 million years ago when this part of Alabama was submerged under the sea”.

So the hadrosaur tooth turned up in a layer from the age of dinosaurs that was once deep ocean.

Experts say this makes the find exceptionally rare – a dinosaur apparently washed out to sea during the Late Cretaceous. It immediately raised the stakes: this was no ordinary fossil hunt.

Dinosaur Backdrop

Alabama has dinosaurs, but only in small numbers. Because the state has no Jurassic-age rocks, every dinosaur bone or tooth came from Late Cretaceous animals swept out into that inland sea.

Paleontologists emphasize that fossils of non-flying dinosaurs are very rare here: “Dinosaur fossils are very uncommon in Alabama”, and those found were likely “dinosaurs that died and were then washed out to sea”.

The few known dinosaur remains include hadrosaurs (duck-bills) and even tyrannosaurs, all dating to ~84–66 million years ago.

Mosasaurs and ammonites dominate the story, making this hadrosaur tooth an extraordinary missing piece of Alabama’s prehistoric puzzle.

Layers of History

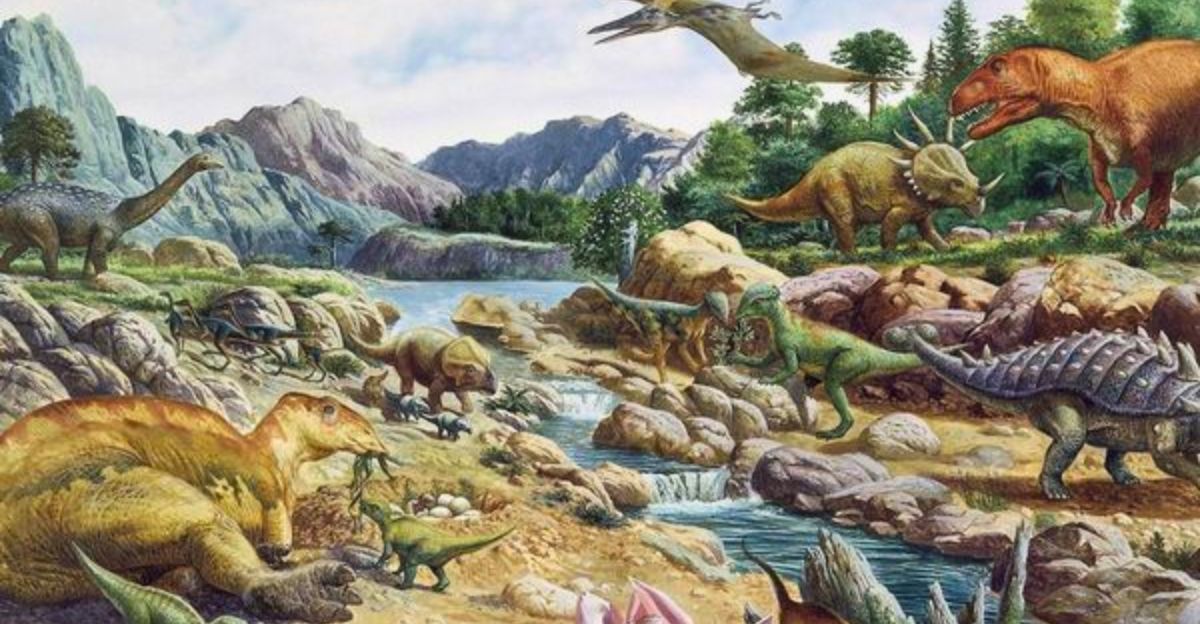

During the Late Cretaceous, the land where Greene County now sits was mostly underwater. A shallow sea covered much of present-day Alabama, allowing marine life to flourish.

Fossils from that time include abundant oysters, ammonites and marine reptiles in the chalks. Only the highest coastal plains were dry. Those rare land areas supported subtropical forests and dinosaurs like armored sauropods and duckbills.

When dinosaurs died near these shores, their bodies occasionally washed into the sea.

What survived the journey were the hardest parts – like teeth – washed out to sea, scavenged by sharks, then buried in that seafloor mud.

Tooth Found

The excitement reached a climax on July 26, 2025, when Dr. Friel spotted a gleaming find. Catalogued as ALMNH: Paleo:22015, the specimen turned out to be the base of a hadrosaur’s tooth.

For Friel, this was unprecedented. “I have been doing these trips for the past ten years,” he later said, “but this was the first time I have ever found a dinosaur fossil”.

Holding the shiny tooth, Friel knew immediately its significance.

It marked a rare direct link to the dinosaurs that roamed Alabama’s ancient shorelines and became a highlight of the museum’s collection.

Local Impact

The donated tooth now serves as hard evidence that Greene County once teemed with dinosaurs.

For scientists and educators, this is huge: it brings Alabama’s prehistoric world into the classroom and community. Museum staff say such discoveries broaden what local students and residents learn about their own land. In fact,

Alabama’s fossil enthusiasts are eager to showcase finds like this at schools and exhibits.

By placing the hadrosaur tooth on public display, the Museum can tell people here how diverse the state’s Cretaceous life really was.

Personal Discovery

Dr. Friel recalls the moment vividly. “When I first picked it up, I thought it was just another odd piece of bone… however, when I turned it over and saw that it had a shiny enameled surface, I was fairly certain it was a tooth”.

He laughed that day, saying he had hoped someone would unearth something dinosaurian, “but little did I know that I would be the lucky one to find a dinosaur fossil this year!”.

To Friel — a veteran educator who’s led thousands of people on creek digs — the discovery was thrilling.

Even after a decade of fossil hunts, he finds that moment of recognition “was like lightning striking twice” on the same summer day.

Scientific Validation

The hard facts of the find were confirmed quickly. Two university paleontologists on the trip examined the specimen and agreed it is indeed a hadrosaur tooth.

Curator Dr. Adiel Klompmaker explained how such a land animal’s tooth came to rest in a creek fossil layer: the hadrosaur likely died near the Cretaceous shoreline and its body floated out to sea, where scavengers ate the soft parts.

“The hard parts such as bones and teeth were scattered across the ocean floor and some got buried to be found ~84 million years later,” he said.

With this verification, the tooth became a new data point for understanding Alabama’s vanished ecosystems.

Bigger Picture

Hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) were widespread herbivores in the Late Cretaceous. Some North American species grew 30 to 50 feet long.

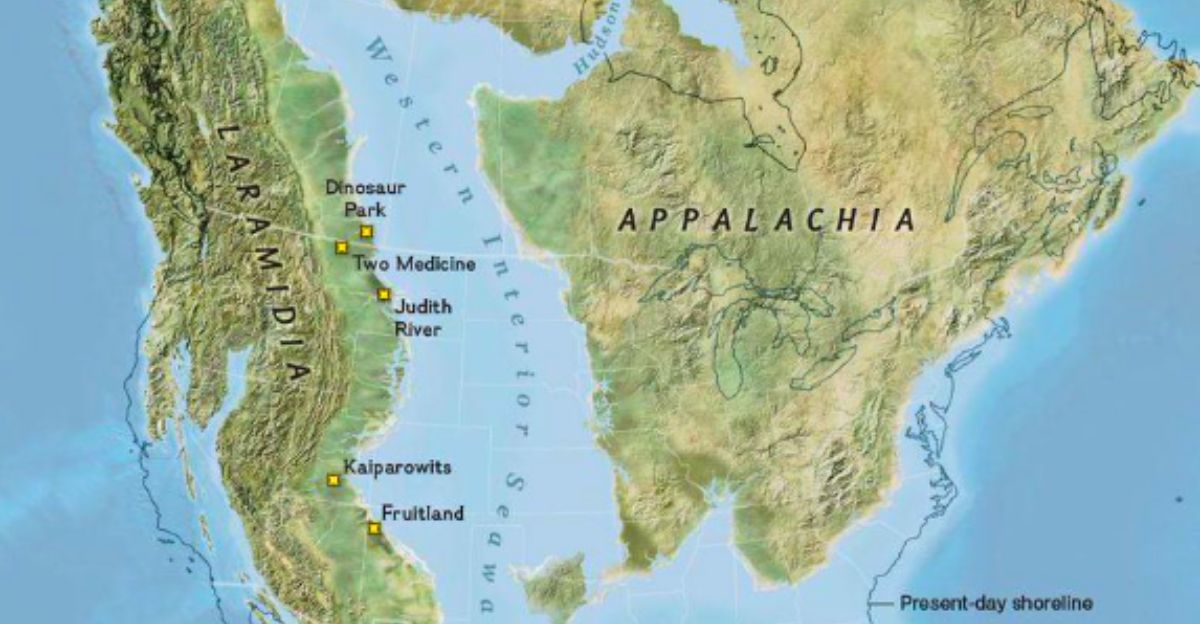

On the vast western landmass, thousands of hadrosaur fossils have been found. In the isolated East (Appalachia), remains are scarce. Alabama’s hadrosaur finds (like this tooth and others such as Eotrachodon) are among the only eastern examples.

In fact, an expert at the Yale Peabody Museum notes that while the West has been the fossil hotspot, “the eastern part of the country contains its share of treasures”.

This discovery thus opens a window on an ancient world otherwise poorly known in the Southeast.

Donation

Public fossil hunts like this one rely on sharing finds. Participants are encouraged to donate any scientifically important fossils for curation.

As Dr. Friel explains, “We only ask that participants donate exceptional finds like this dinosaur tooth… so they can be added to the paleontology collection and be made available to researchers or possibly used for public display”. In other words,

The hadrosaur tooth now belongs to the University’s collection.

It will be conserved for study and may eventually go into a museum exhibit, letting everyone see this rare piece of Alabama’s past.

Stakeholder Hopes

The museum honors those who contribute. In this case, Friel himself is listed as the collector of record, and he will receive an official certificate acknowledging the donation.

Such recognition encourages community members to participate in science.

The message is clear: your chance find can make it into the scientific record and even inspire new questions.

For visitors and citizen-scientists, knowing that an everyday fossil hunt could yield a dinosaur tooth motivates curiosity and stewardship of local natural history.

Leadership Continuity

The success of these excursions owes much to Dr. Friel’s leadership. For over 10 years, he has led Alabama Museum fossil trips and mentors new enthusiasts.

Over that time, he’s learned exactly which fossils are common (shark teeth, ammonite fragments) and which are extraordinary (mosasaur bones, dinosaur bits).

His enthusiasm is infectious – he promises first-time participants that they will find something exciting.

By working side-by-side with amateurs, Friel bridges academia and the public, ensuring that these digs are not just one-off events but a continuing tradition of discovery.

Strategic Expansion

Interest in Alabama’s fossils is growing. The museum now promotes its programs more widely and partners with local clubs. For example, enthusiasts from the Alabama Paleontological Society and other groups regularly join digs and share finds.

Each year, the number of participants climbs, and the museum posts discoveries on social media, sparking even broader engagement. As more unique specimens enter collections, Alabama’s fossil heritage takes on new relevance.

What was once considered a mostly marine record is now recognized as telling a richer story that includes creatures from land and sea alike.

Expert Voices

Experts underscore the rarity of this find. Dr. Klompmaker reiterates that virtually all dinosaurs in Alabama must have floated out to sea after death.

“What probably happened is that the hadrosaur died close to the shore… and then floated into the ocean, where it served as food for scavengers,” he said. “The hard parts… were scattered across the ocean floor and some got buried to be found ~84 million years later”.

In short, only the toughest bits—like this tooth—survived to fossilize.

This fragment now provides hard evidence for hypotheses about how Alabama’s land and sea life intersected in prehistory.

Looking Forward

The discovery opens new questions: How many more dinosaurs might Greene County’s creeks be hiding? Scientists hope future trips will turn up even more.

Clues abound – in fact, one of the UA researchers notes that only sporadically do new dinosaur fossils appear here. “Only once in a while does a new dinosaur fossil show up,” the museum report observes, yet already two dinosaur toe bones were found on an Alabama dig in 2024.

Every find adds a chapter to Alabama’s prehistoric story and fuels the anticipation that the next dig could change what we know.

Policy & Preservation

By law, fossils on private land in Alabama are not regulated, so donation is voluntary. (On federal lands, by contrast, the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act requires fossils to be managed by agencies.) In

Alabama’s museums follow scientific best practices. They carefully catalog and curate important specimens.

For example, Friel’s tooth has been accessioned into the Alabama Museum of Natural History’s collection, and the museum ensures it is preserved under proper conditions.

This stewardship approach – while not mandated by state law – reflects a growing emphasis on protecting fossils for research and public education.

Global Comparisons

Hadrosaur fossils abound in Western North America but are scarce in the East. In Late Cretaceous North America, a great inland seaway divided the continent.

The western land (Laramidia) produced rich fossil beds, while the eastern land (Appalachia) remained relatively isolated.

Paleontologist Chase Brownstein notes that “while the western United States has long been the source of exciting fossil discoveries, the eastern part of the country contains its share of treasures”.

Alabama’s rare tooth thus helps fill a continental gap. It suggests that creatures were traversing or drifting across the ancient seas more than previously documented, highlighting differences in dinosaur populations on each side of the seaway.

Environmental Echoes

This tiny tooth speaks of vast prehistoric landscapes. During the Cretaceous, Alabama’s environment was a complex mix of subtropical coasts and deep seas.

Southern Alabama’s chalk seas teemed with marine turtles, whales and sharks, leaving behind countless marine fossils. Simultaneously, higher ground hosted dense forests.

Armored dinosaurs and duckbills like our hadrosaur roamed those woodlands, alongside early tyrannosaurs.

Each fossil find, marine or terrestrial, adds detail to this picture. In this case, the hadrosaur tooth strengthens evidence that lush forests skirted an ancient shoreline rich in life both above and below the water.

Cultural Fascination

Exciting finds like this spark public imagination. As Dr. Friel observes, the museum’s fossil excursions “have proven to be exceedingly popular” and routinely fill every available spot.

School groups, families and retirees join in, always hopeful for a discovery. Museums report that when a dinosaur fossil is announced – even just a tooth – it creates a buzz in the community.

It connects people to a shared past and reminds them that science can happen anywhere, even in a rural creek.

By showcasing these finds in exhibits and programs, educators harness the awe of discovery to teach geology, biology and history to curious visitors of all ages.

Bigger Questions

Now safely in the museum’s collection, this tooth awaits study and perhaps public display.

It bridges science and community: a chance find that involved volunteers, educators and researchers alike. Each discovery of an ancient creature “rewrites” a bit of Alabama’s deep history.

It reminds us that the story of life on Earth is long and still unfolding. As experts put it, every new fossil emphasizes how much remains to be unearthed in our own backyard.

The hadrosaur tooth is more than a curiosity – it’s a clue that the secrets of Alabama’s past are still waiting in the stones.