Deep in Ethiopia’s Afar region, Hayli Gubbi slumbered for 12,000 years—the entire Holocene epoch, spanning all of recorded human civilization. Then, on Sunday, November 23, 2025, it exploded. Around 8:30 AM UTC, ash rocketed 9 miles skyward in a column that caught the sparsely populated region completely off guard.

The eruption lasted for hours, shattering a silence so complete that no evacuation plans existed, no sirens sounded, and no one remembered what to do. A sleeping giant had finally stirred.

A “Sudden Bomb” Descends

Residents felt it first—a loud explosion, followed by a shock wave rippling through the villages near the volcano. “It felt like a sudden bomb had been thrown with smoke and ash,” said Ahmed Abdela, an Afar resident, to reporters. Within minutes, the sky darkened. Ash buried grazing lands and covered villages, including Afdera.

Mohammed Seid from the Afar regional government confirmed the toll: “Many villages have been covered in ash, and as a result their animals have little to eat.” Fortunately, no human deaths or livestock losses were recorded—only the beginning of a livelihood crisis.

Where Earth’s Plates Collide

Hayli Gubbi sits in one of Earth’s most geologically restless zones: the Rift Valley, where three tectonic plates—African, Arabian, and Somali—are slowly pulling apart at 0.4 to 0.6 inches yearly. This is the Afar triple junction, where Earth’s crust stretches and thins, allowing hot rock from deep within to rise and melt into magma.

The East African Rift System, which includes this region, hosts some of the planet’s most active volcanoes. Understanding why Hayli Gubbi erupted means understanding this violent planetary machinery.

Magma Stirring Beneath

Scientists didn’t expect Hayli Gubbi to erupt—nothing in its known history suggested it would. Yet clues emerged. In July 2025, nearby Erta Ale volcano erupted in ash. Satellite data revealed massive magma intrusion spreading outward beneath the surface, reaching almost 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) below Hayli Gubbi.

Researcher Juliet Biggs observed white clouds at the summit and measured ground uplift of several centimeters—subtle signals that something deep was changing. The mountain was waking up.

A Rare Explosive Blast

Shield volcanoes like Hayli Gubbi typically ooze lava flows, not towering ash columns. Yet on November 23, it did exactly that. The reason lies in chemistry: the volcano taps into silica-rich magma (trachyte and rhyolite), not just basaltic lava. Silica-rich magma is thicker, trapping more gas inside.

When pressure builds and releases suddenly, you get an explosive eruption with an umbrella cloud. “To see a big eruption column like that is really rare in this area,” Biggs noted to researchers.

The Ash Cloud Races Across Continents

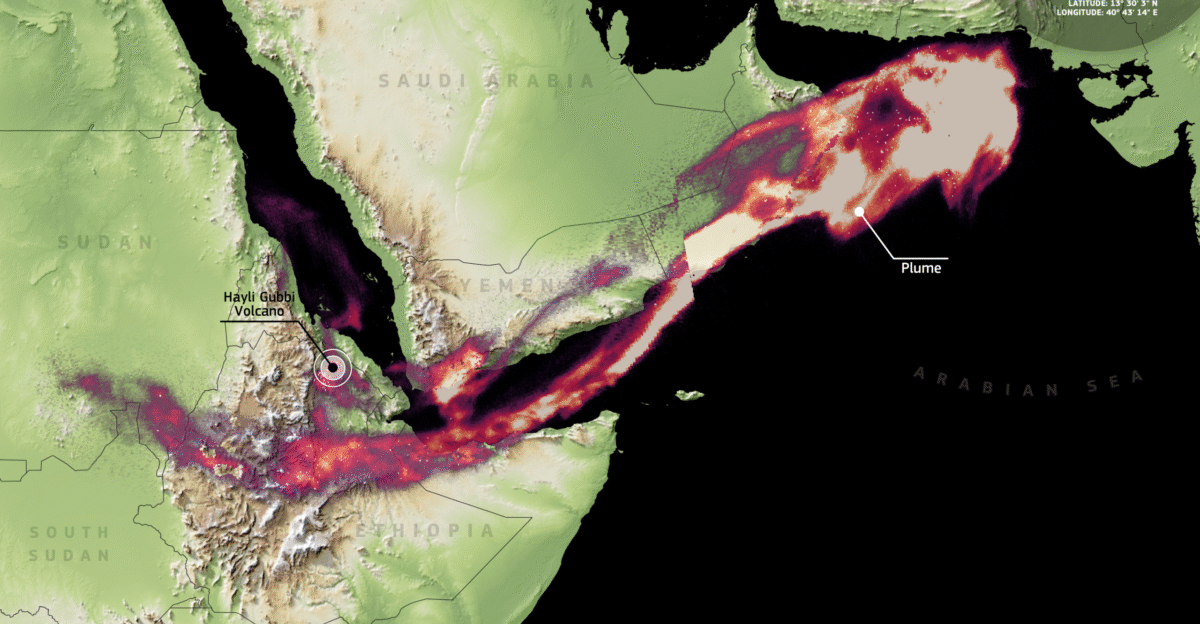

The eruption column didn’t stay put. Subtropical jet streams grabbed it and carried ash eastward at tremendous speed. By Monday, the plume had drifted over Yemen and Oman, crossing the Arabian Sea. By Tuesday, it had swept across northern Pakistan and northern India, traveling thousands of kilometers in days.

The Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre confirmed the plume extended approximately 3,700 kilometers from Ethiopia to the Arabian Sea. Satellite data captured sulfur dioxide spreading across the region—volcanic emissions leaving their mark on the upper atmosphere.

Aviation Grounded and Routes Disrupted

Volcanic ash is a pilot’s nightmare: abrasive particles infiltrate engines, contaminate fuel, reduce visibility, and pose serious safety hazards. Airlines scrambled. Air India cancelled at least 11 flights; Akasa Air suspended multiple Middle Eastern routes on November 24-25. Pakistan’s aviation authority issued volcanic ash advisories—a first in the nation’s history.

IndiGo redirected flights, and carriers worldwide rerouted planes on longer routes, burning extra fuel and disrupting thousands of passengers. The ash had closed invisible corridors in the sky.

A Population Breathing Concern

Millions across Yemen, Oman, India, and Pakistan were potentially exposed to the ash plume drifting overhead. In Delhi, already burdened by severe pollution, authorities initially worried the volcanic ash would worsen conditions.

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) offered reassurance: ash was dispersing at high altitude and moving rapidly eastward, making significant ground-level impact unlikely.

Livestock Herders Face Crisis

For Afar pastoral communities, the eruption was catastrophic. The economy depends almost entirely on livestock herding—cattle, camels, goats, sheep grazing across drylands. Grazing lands near the volcano were buried in ash. Animals had no vegetation to eat, forcing herders to move herds to unaffected areas or improvise food sources.

The Afar is already harsh: scorching heat, sparse rainfall, limited resources. Ash-covered pastures trigger malnutrition in livestock, herd mortality, and economic collapse for families dependent on animals.

No Warning, No Precedent

Unlike volcanoes with documented eruption histories, Hayli Gubbi arrived with no warning system. The Smithsonian’s Global Volcanism Program confirms zero Holocene eruptions—no recorded activity during all 12,000 years of human history. Local residents had no evacuation drills.

The nearest village had never experienced such an event. “It really just shows how understudied this region is,” Biggs told researchers. The volcano may have erupted during the past 12,000 years, leaving no trace in records of a remote, sparsely populated terrain.

Was This One Time or the Beginning?

Why did Hayli Gubbi erupt after 12,000 years of silence? Earth scientist Derek Keir, who was in Ethiopia during the eruption, collected ash samples Monday that may provide answers. Ash composition and lava flows could reveal whether true dormancy existed or if eruptions went unrecorded.

More broadly: Does this eruption signal a new active phase in the Rift Valley?

Other “Dead” Volcanoes Could Wake

If a 12,000-year-dormant volcano can suddenly erupt, what about thousands of supposedly “extinct” or “dormant” peaks worldwide? Experts caution that human definitions of dormancy don’t match geological timescales. A volcano quiet for 5,000 or 10,000 years may still harbor active magma plumbing.

The Afar alone contains dozens of volcanic peaks, most classified as dormant based on historical records spanning only hundreds of years—a geological blink.

The Rift Valley’s Violent Reshaping

Hayli Gubbi is part of grander geological drama. The Afar triple junction—where three tectonic plates diverge—is one of only two places on Earth where a mid-ocean ridge can be studied on land; Iceland is the other.

Over millions of years, the Afar will be flooded by the Red Sea, creating a new ocean basin as Africa and Arabia separate. The current rifting process is reshaping the landscape: deep valleys between elevated ridges, shaped by normal faults and volcanic activity

Communities Bracing for Uncertainty

In the days following eruption, residents of nearby villages faced ongoing challenges. Ash coated crops, water sources, and animal feed. Respiratory issues emerged as families breathed fine volcanic particles. Water contamination became a concern as ash and sulfur dioxide settled into wells.

Scientists deployed monitoring equipment to track the volcano. Seismic networks were enhanced. Satellites maintained constant watch. The Afar, after 12,000 years of quiet, faces new reality: the volcano is no longer sleeping.

What Experts Say Comes Next

Volcanologist Simon Carn at Michigan Technological University and researcher Juliet Biggs are analyzing ash samples to determine if Hayli Gubbi was a one-off eruption or signals a new eruptive phase in the Rift Valley. If the latter, neighboring Erta Ale could intensify.

The eruption has fundamentally shattered assumptions about dormancy: 12,000 years of silence no longer guarantees safety. Thousands of supposedly “extinct” volcanoes worldwide now require urgent reassessment. The sleeping giants, it seems, were never truly asleep