It’s 2 a.m. Thursday in northwestern Kerr County. Weather alerts are buzzing across phones—not because of another routine thunderstorm, but because four months after a catastrophic flood killed over 100 people in a single night, the forecast is pointing toward the same vulnerable canyons.

Governor Abbott has already positioned Black Hawk helicopters, rescue teams, and seven state agencies on standby. For 75,000 residents in the target zone, the reality is sobering: this could happen again.

When November Weather Turns Dangerous

Late November typically brings dry, stable weather across Texas. This Thursday won’t be typical. National Weather Service forecasters are monitoring atmospheric moisture levels approaching 1.75 inches of precipitable water—a benchmark usually reserved for peak July heat.

Unseasonable warmth across the South is the culprit, allowing the air to hold substantially more moisture than it should for this time of year. When that moisture collides with the Hill Country’s terrain, the conditions become dangerous.

Storms Stacking Over Vulnerable Ground

What makes this system particularly concerning is a meteorological phenomenon known as “training”—when successive storms move along the same track, dumping rain repeatedly over the same areas. Forecasters expect 1 to 3 inches regionally, but in the training zones, isolated totals could reach 6 to 8 inches.

The National Weather Service warns that rainfall rates may hit 3 inches per hour during the heaviest bursts. When you combine that intensity with the Hill Country’s already-saturated ground, water has nowhere to absorb—it simply runs downhill fast.

Why This Geography Matters

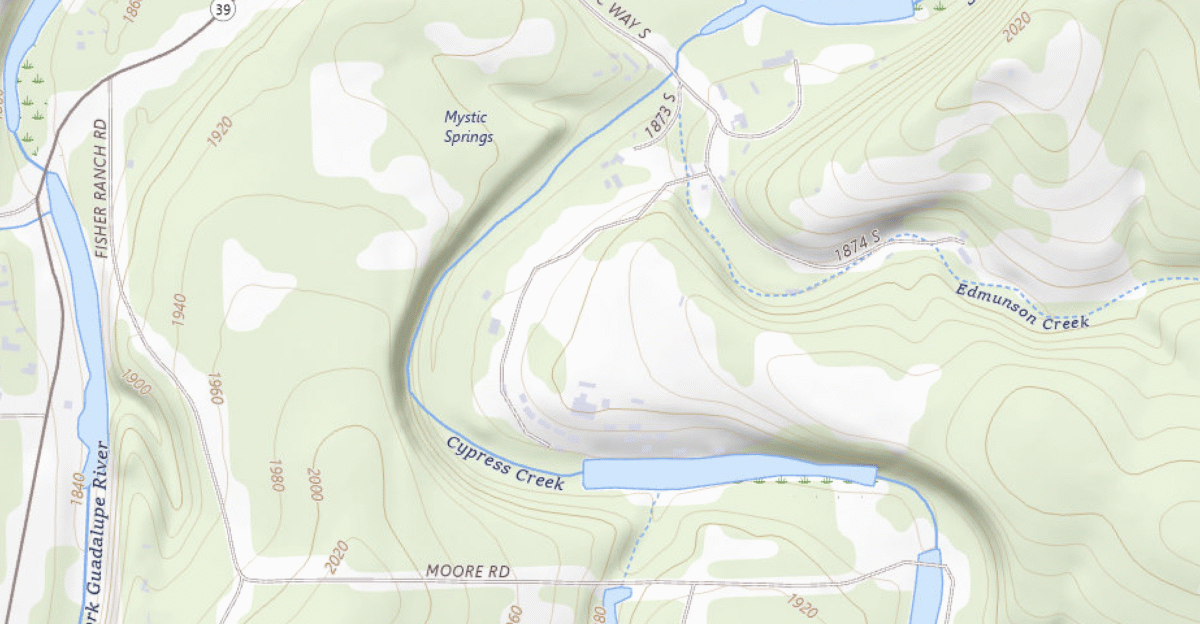

The Texas Hill Country’s dramatic landscape—narrow limestone canyons, rocky substrate, shallow soil—creates a perfect storm environment for flooding. Water can’t soak into the ground; it races downhill through creeks and into rivers that respond within minutes, not hours.

In July, this dynamic played out with terrifying speed. The Guadalupe River at Hunt went from 11 feet to 37 feet in less than an hour. Residents who witnessed it described the water behavior of the river as it had never exhibited before.

The Same Vulnerable Areas Face Threat Again

Now, as storms track toward those same headwater forks, the risk profile is impossible to ignore. Forecasters are monitoring storms as they position themselves over the northwestern forks of the Guadalupe—the exact location where Camp Mystic is situated.

The Flood Warning specifically mentions the Guadalupe near Hunt—the same location, the same vulnerability. For a community still recovering, the targeting feels cruelly precise.

The Human Cost Still Fresh

On July 4, campers sleeping in riverside cabins at the century-old all-girls camp woke to rising water with almost no warning. By dawn, 27 young people were dead. Across Kerr County, over 100 people lost their lives that day, part of 135 deaths across Central Texas.

Those families are still grieving. Survivors are still processing. And this week, as another storm system approaches, the vulnerability feels raw.

What Went Wrong in July

July’s flood exposed critical gaps in emergency response. According to CNN and the Associated Press, communication breakdowns meant residents didn’t receive alerts until hours after water had already crested.

When a firefighter requested an emergency alert at 4:22 a.m. as water was rising, dispatch delayed it for approval. The first CodeRED alert didn’t go out for 90 minutes. Some residents got messages after 10 a.m.—too late. Those failures weigh heavily on officials.

How the Response Is Different Now

This week’s response is fundamentally different. Governor Abbott activated Level III emergency readiness on Wednesday, positioning swiftwater rescue teams from Texas A&M, Black Hawk helicopters from the National Guard, and rescue boats from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Seven state agencies are running 24-hour operations. The mobilization reflects a determination not to repeat those failures. Officials are treating this threat with the utmost urgency.

The Deadliest Hours: Pre-Dawn Thursday

The window of most significant danger is Thursday before sunrise, when heavy rain converges with zero visibility. The Hill Country contains over 100 low-water crossings—spots where roads dip through creek beds that sit dry most of the year. During flash floods, they become perilous.

Six inches of moving water can knock someone off their feet; two feet can lift a vehicle. When darkness combines with fast-moving water, people can’t judge the depth or strength of the current.

The Life-Saving Rule Everyone Must Follow

Most flash flood deaths happen in vehicles during exactly these conditions. The National Weather Service’s “Turn Around, Don’t Drown” message isn’t just cautionary language—it’s the single rule that actually saves lives. If water crosses a road, turning around immediately is the only safe choice.

Emergency responders are clear: once water starts moving through Hill Country canyons, rescue becomes extraordinarily difficult. The safest place is high ground, reached before the water rises.

Layered Hazards Beyond Flooding

The storm system brings secondary threats that compound the danger. Damaging winds could down trees and power lines. Large hail threatens vehicles and structures. Isolated tornadoes are possible as the system’s rotation evolves. Multiple regions across Texas face these hazards on Thursday and Friday.

For residents, multiple ways to stay informed are essential—such as weather alert radios, smartphone notifications, and local news coverage—because missing a pre-dawn warning could mean missing the alert that matters most.

Another System Approaching

Thursday’s storm system won’t be the end. Forecasters are already tracking a second system scheduled to arrive Sunday night into Monday, November 24-25. While that follow-up event carries a lower risk level, the timing is problematic: the Hill Country’s soil will still be saturated from Thursday’s rain.

Water won’t have been fully absorbed. Creeks and rivers that rise on Thursday may not recede before Sunday’s rainfall arrives.

Understanding the Shift in Seasonal Weather

Climate patterns are changing in ways meteorologists are beginning to understand but not yet fully predict. Ongoing unseasonable warmth across the South is fundamentally altering seasonal rainfall patterns.

Warmer air holds more moisture—a principle known as the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship—enabling storms to produce more precipitation when atmospheric conditions are favorable. A precipitable water value of 1.75 inches in November is approaching mid-summer benchmarks.

How Communities Are Preparing

Across the Hill Country, on Thursday, residents are taking measured steps informed by the experience of July. Phones are charging overnight. Weather apps are set to the highest alert levels. Families are having difficult conversations: which rooms are highest in the house? Which neighbors have second stories? Which roads lead to high ground?

Some families have decided not to stay home. They’re packing belongings and driving to hotels in San Antonio or Austin, choosing not to spend another night listening to rain and wondering about the outcome.

The Lesson That Matters Most

The difference between weathering this storm safely and facing tragedy comes down to one principle: treating warnings as immediate action steps, not suggestions to consider. For the 75,000 people in the target zone watching Thursday’s forecast, that’s the hard-learned lesson from July: move early, don’t hesitate, trust the warnings.

The storm is coming. The preparation is ready. The outcome depends on decisions made before the rain arrives.