For generations, the ancient Egyptian city of Akhetaten—built by the controversial Pharaoh Akhenaten—was shrouded in the legend of a devastating plague that supposedly brought about its sudden collapse. Now, after a sweeping 17-year investigation of more than 11,000 burials, researchers have upended this long-held belief, revealing a story not of epidemic catastrophe, but of chronic hardship and systematic labor exploitation.

Challenging a Century-Old Plague Myth

The narrative of Akhetaten’s demise has shaped both scholarly and popular understanding for over a century. Museums around the world have displayed artifacts and crafted exhibits based on the idea that a divine plague punished Akhenaten’s religious revolution. This theory, repeated in textbooks and dramatized in media, became accepted fact despite scant direct evidence. As Dr. Gretchen Dabbs of Southern Illinois University notes, the association between Akhetaten and plague “became a ‘fact’ through repetition,” prompting a widespread need to revise educational materials and public displays as new findings emerge.

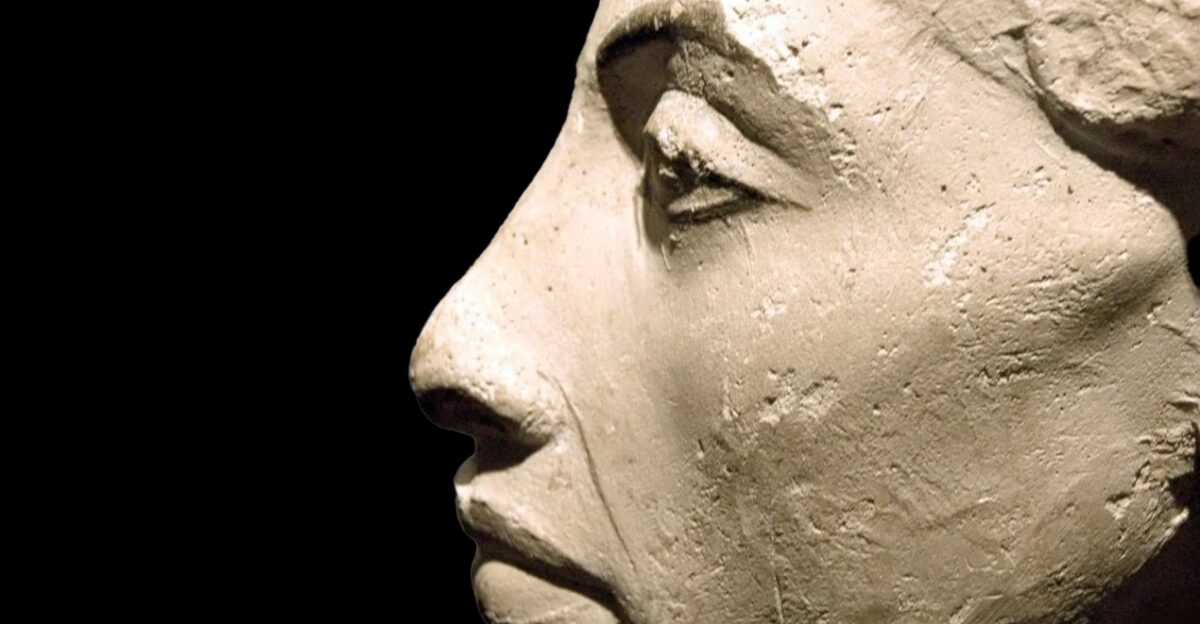

A City Built on Radical Change

Akhetaten, meaning “Horizon of the Aten,” was established around 1346 BCE as the centerpiece of Akhenaten’s unprecedented shift to monotheism, focusing worship on the sun disk Aten. The city rose rapidly along the Nile’s east bank, stretching eight miles and constructed largely from mud brick. Yet this bold experiment was short-lived: after Akhenaten’s death around 1332 BCE, the city was systematically abandoned, its fate long attributed to a mysterious epidemic.

Bioarchaeological Breakthroughs and the Absence of Epidemic

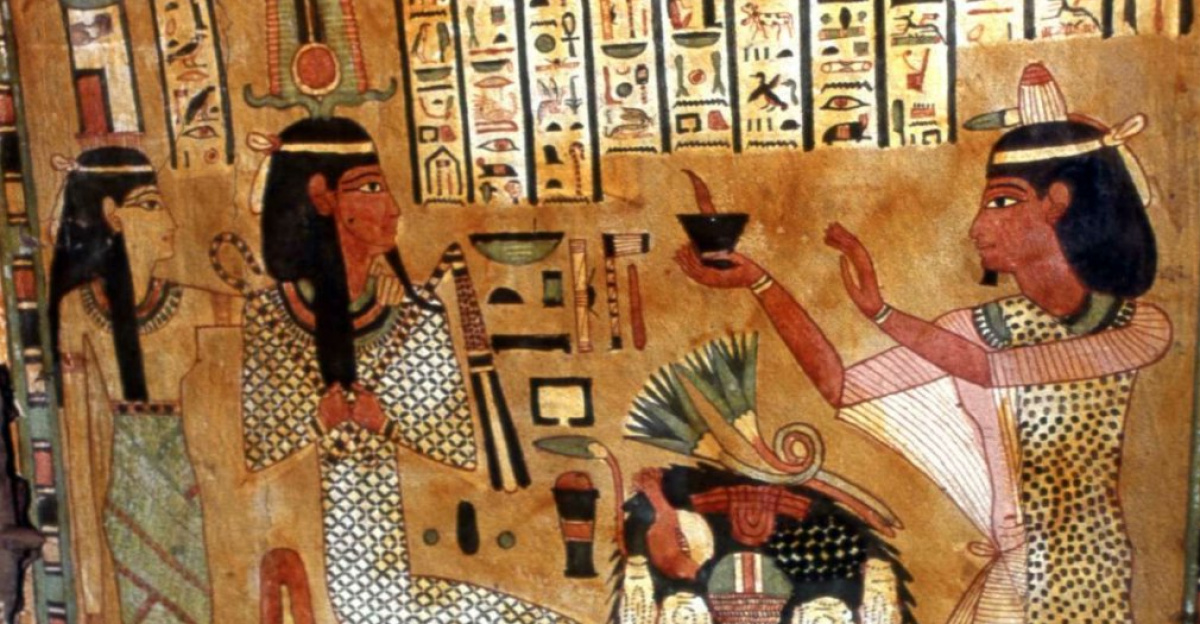

Recent advances in bioarchaeology have enabled researchers to identify the telltale signs of ancient epidemics—such as mass graves, hurried burials, and sudden mortality spikes—with far greater precision. Applying these methods to Akhetaten, a team led by Dr. Dabbs and Dr. Anna Stevens of Monash University meticulously analyzed over 11,000 burials from four major cemeteries, excavated between 2005 and 2022. Contrary to the plague narrative, they found no evidence of mass or chaotic burials. Instead, bodies were interred with care, accompanied by grave goods and wrapped according to tradition. Mortality patterns remained consistent with ordinary life, not the abrupt devastation of an epidemic.

While regional texts from the Late Bronze Age mention disease outbreaks elsewhere—such as the Hittite “plague prayers” and references in the Amarna Letters—none specifically cite an epidemic within Akhetaten itself. Dr. Dabbs cautions against using evidence from other locales to make claims about Akhetaten, emphasizing the importance of local data.

Revealing the Real Hardships: Labor and Malnutrition

The skeletal remains from Akhetaten tell a different story—one of chronic hardship rather than sudden disaster. Many skeletons bore marks of childhood malnutrition, including linear enamel hypoplasia, and signs of intense physical labor, such as spinal trauma and degenerative joint disease. Adult statures were notably short, reflecting long-term undernutrition. These findings point to a population enduring food insecurity, heavy workloads, and limited resources—conditions that produce chronic stress and elevated mortality, but not the abrupt patterns of epidemic disease.

One cemetery, the North Tombs Cemetery, revealed a striking demographic anomaly: most individuals buried there died between the ages of five and twenty-five. This youth-heavy pattern suggests a workforce cemetery, likely for laborers subjected to grueling conditions. The “plague” myth, researchers argue, may have obscured the reality of systemic labor exploitation at Akhetaten.

Debate and Disciplinary Reckoning

Not all scholars are ready to abandon the epidemic theory. Some point to royal family death clusters and religious iconography—such as statues of Sekhmet, the goddess of pestilence—as possible indirect evidence of disease. Others note that certain fast-acting diseases may leave little trace in bone. However, the comprehensive analysis of burial practices and mortality patterns at Akhetaten has shifted the consensus toward explanations rooted in social and economic factors rather than epidemic catastrophe.

The study’s rigorous methodology—combining paleodemography, taphonomy, and advanced statistical analysis—sets a new standard for investigating ancient disasters. It also prompts a broader reckoning within Egyptology, raising questions about other long-standing “facts” that may rest on circumstantial or misinterpreted evidence.

A New Framework for Understanding the Past

The Akhetaten findings are already reshaping museum exhibits and educational materials worldwide, as institutions move to correct the historical record. The research highlights the value of syndemic theory, which examines how multiple health and social problems interact to produce elevated mortality, rather than seeking a single catastrophic cause. For Akhetaten’s residents, it was the intersection of malnutrition, harsh labor, and inadequate living conditions—not plague—that proved most deadly.

This paradigm shift underscores the importance of testing dramatic historical narratives against local, material evidence. As Dr. Dabbs and her colleagues demonstrate, even the most entrenched stories can—and should—be revised in light of new data. The legacy of Akhetaten now stands as a testament to the power of scientific inquiry to rewrite history, offering a more nuanced and evidence-based understanding of the ancient world.