Recycling aluminum cans is a powerful economic and social tactic with benefits beyond the environment. The story of a man who recycled almost 500,000 cans to buy a two-bedroom home exemplifies the relationship between financial empowerment and environmental stewardship. Among recyclables, aluminum cans are special because they can be recycled endlessly without losing quality and only require around 5% of the energy needed to make new aluminum.

Recycling such a vast amount of material yields significant financial gains, converting what many consider to be waste into funds for significant investments like real estate. This story challenges accepted notions of poverty, homelessness, and sustainability by promoting recycling as a valid means of achieving both financial success and environmental stewardship.

The Historical Background of Resourcefulness and Recycling

Recycling has a long history and was traditionally done more for practical reasons than out of concern for the environment. Reusing metals and materials has been done for centuries, long before mass production became the norm due to industrialization. Reduce, reuse, and recycle were highlighted as the cornerstones of sustainable living by the modern recycling movement, which gained traction in the 20th century.

The historical narrative of resourcefulness, maximizing value from available materials, that shaped early economies, is echoed in this man’s endeavor. The amount of recycling required to pay for a house demonstrates how communities used to prosper from both individual and group recycling initiatives, reviving an antiquated economic theory tailored to modern issues and urban life.

Economic Trends in Housing Affordability and Recycling

Unconventional financial strategies have been prompted by global housing affordability crises. Recycling initiatives, particularly those that focus on aluminum cans, are evolving into microeconomic instruments for those with low incomes and environmental concerns.

Recycling a single aluminum can generates a small financial return, but when hundreds of thousands of cans are recycled, the total amount of money raised increases significantly. This recycling-to-homeownership model offers two advantages: it reduces waste and makes asset acquisition possible, which is in unique alignment with the principles of the circular economy. By proposing alternate credit channels and wealth-building strategies separate from conventional banking or loan systems, it challenges established financial systems.

Psychological Aspects: Recycling as a Means of Identity and Empowerment

This man’s success is based on psychology that goes beyond financial gain. Recycling so many cans requires self-control, tenacity, and a reevaluation of oneself based on intentional environmental action. The act of collecting cans changes the way society perceives waste and turns it into a sign of empowerment and agency.

By encouraging a growth mindset and environmental identity that inspires ongoing action, it challenges the fatalistic narratives frequently connected to homelessness and poverty. This change in mindset is encouraging and a real-world illustration of how eco-friendly actions align with social inclusion and personal growth.

Implications for Sustainability and the Environment

Significant environmental benefits result from recycling 500,000 cans, including the preservation of natural resources, the saving of thousands of gallons of water, and a general decrease in greenhouse gas emissions. Aluminum cans make up a significant amount of recycled metals worldwide, and a closed-loop sustainability model is highlighted by their long-lasting recyclability.

The procedure reduces the amount of toxic leachate contamination and landfill overcrowding. Recycling is reinforced as a crucial sustainability lever by this example, which supports the ecological narrative that individual acts, when sufficiently scaled, make a meaningful contribution to addressing global environmental challenges.

Recycling at This Scale Presents Challenges

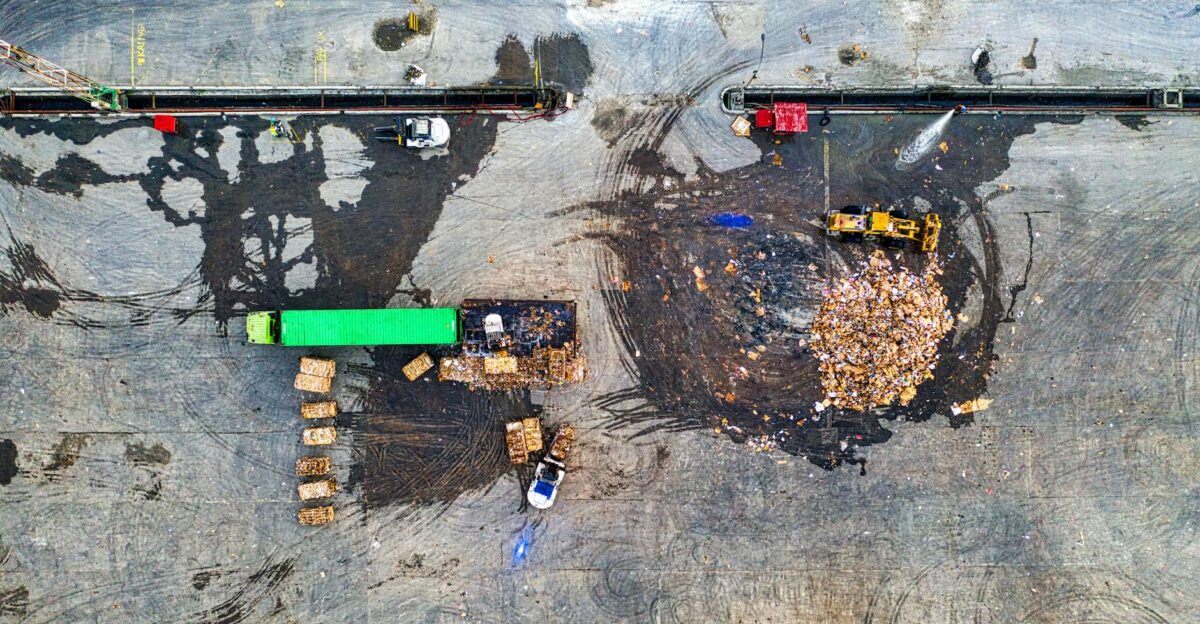

The logistical and physical demands of collecting almost half a million cans indicate difficulties that go beyond straightforward financial analysis. It calls for strong community networks or a single, unrelenting effort that is frequently underestimated in discussions of waste management. The time commitment and physical space required for collection, storage, and transportation highlight the labor intensity of large-scale recycling that is often disregarded.

This extrapolation highlights weaknesses in the current waste management infrastructure as well as areas for innovation that could democratize access to recycling incentives, such as better recycling facilities, mobile collection centers, or online marketplaces that link recyclers and buyers.

Innovative Technologies and Models for Recycling

Traditional recycling models are being revolutionized by emerging technologies such as digital redemption platforms, AI-powered sorting, and app-based community organizing. These developments make it easier for people to engage in recycling activities successfully and financially. For instance, real-time tracking of can collection and redemption values is possible through mobile apps, and automated sorting maximizes material quality while cutting expenses.

Anecdotal success stories can be turned into scalable, replicable frameworks that have a broader socioeconomic impact thanks to these technological advancements. These models promote inclusive environmental economies and sustainable urban development.

Second-Order Impacts on Social Policy and Urban Development

This model of recycling to home ownership suggests revolutionary avenues for urban development. Innovative recycling programs could simultaneously address the intertwined crises of waste management and affordable housing in cities. By incorporating environmental sustainability into social welfare, policymakers could provide subsidies or housing credits to encourage widespread recycling.

This two-pronged strategy can lessen the cycle of poverty, promote thriving communities, and lessen urban blight. By normalizing sustainable wealth creation through environmental engagement, such programs’ institutional support and social acceptance could have an impact across generations.

Contrarian Opinions and Criticism

Reliance on recycling for significant financial gains may be criticized for romanticizing individual effort over resolving structural injustices and diverting attention from systemic solutions required for the housing and poverty crises. Recycling could be portrayed as a cure-all, drawing focus away from more extensive socioeconomic changes.

Furthermore, the financial viability of such initiatives may be jeopardized by shifting commodity prices. However, these criticisms highlight the need to frame recycling initiatives as supplementary tactics rather than stand-alone solutions within larger policy and economic frameworks.

Comparative Analysis: Recycling as a Driver of the Economy

This example is mirrored in a number of instances around the world, including deposit-return programs in European nations that significantly increase recycling rates and give money to underserved populations, and Brazilian scrap collectors (also known as “catadores”) whose recycling efforts benefit families and communities.

These examples show how organized recycling initiatives support both environmental restoration and social mobility at the same time. The success stories improve livelihood and ecological metrics by offering scalable lessons on how to incorporate informal recyclers into formal economies.

Cultural Storytelling and the Ethics of Recycling

Recycling has cultural significance that is influenced by environmental ethics and local values. Reusing waste is a profound way for some cultures to show their respect for the natural world.

Enhancing the home-buying experience through recycling subverts popular consumerist narratives and fosters a society in which environmental stewardship and individual success coexist. Community pride, sustainable living, and a shift in success metrics from material excess to thoughtful consumption and stewardship are all possible with this ethic.

Economic Models that Describe the Value Creation of Recycling

Recycling creates value by reducing waste and closing resource loops, according to economic frameworks like environmental economics and the circular economy.

Recycling internalizes environmental costs that conventional linear economic systems have previously disregarded, turning “externalities” into assets. This conversion demonstrates a model where individual initiative is in line with the good of society by providing financial empowerment to individuals while reducing public expenses related to waste management and environmental degradation.

The Function of Institutions and Policies in Promoting Results

To maximize the social and economic advantages of recycling, institutional support is essential. By putting in place deposit-return programs or offering logistical assistance, municipalities lower obstacles for individual recyclers and foster enabling environments.

Recycling could be included in social grants or housing credit programs if public policies acknowledge it as a source of revenue, turning anecdotal successes into opportunities for broader use. Government, business, and community cooperation increases impact and builds resilient ecosystems for sustainable living.

Overcoming Psychological Obstacles by Reusing Achievement

Perceived inconvenience and low motivation as a result of the lack of immediate rewards are common psychological barriers to recycling. By proving real, life-altering advantages, this man’s success dismantles these obstacles and may encourage more widespread behavioral change.

His narrative can be used as an inspiration for creating social marketing campaigns that appeal to sense of self, belonging to a community, and hope for the future—all of which are critical for encouraging recycling habits among a variety of demographics.

Possible Consequences for Environmental Policy

This individual accomplishment backs environmental policies that encourage greater recycling infrastructure and extended producer responsibility. By showcasing their capacity to both economically empower citizens and meet environmental goals, it validates investments in community recycling centers and incentive return programs.

Social equity could be incorporated into sustainability objectives through policy frameworks influenced by such achievements, making ecological responsibility affordable for all socioeconomic groups.

Intersection of Resource Efficiency and the Circular Economy

The principles of the circular economy are demonstrated in this instance; waste converted into resources limits environmental degradation and lessens dependency on virgin materials. Resource efficiency promotes economic resilience in addition to energy conservation (recycling aluminum uses 95% less energy than new production).

By connecting environmental health with observable human benefits, this paradigm shift from linear “take-make-waste” to circular systems has the potential to redefine prosperity and social equity.

Framework Hypothesis: Recycling as a Microinvestment Approach

Large-scale recycling can be viewed as a micro-investment model in which cans serve as micro-assets with compound interest. This contradicts traditional ideas of capital formation that are centered on stocks, real estate, or financial investments. Instead, environmental assets increase their potential for value conversion and liquidity.

Recycling could develop into a recognized investment channel that democratizes wealth creation in line with ecological sustainability if it is combined with microfinance or digital currency systems.

Severe Instances of Recycling’s Global Impact

Extreme recycling efforts around the world, from massive ocean plastic cleanup projects to expansive urban recycling hubs, show how waste management can become a significant economic and environmental driver.

These massive projects are in line with the magnitude of impact demonstrated by this man’s accomplishment, which highlights a continuum between individual endeavor and group global action. These illustrations show how recycling can help address the problems of waste, poverty, and housing.

The Social and Psychological Ripple Effect

Such exceptional recycling initiatives have social and psychological effects on communities in addition to direct financial benefits. They inspire group action, increase environmental awareness, and reframe community values around tenacity and creativity.

This ripple effect demonstrates how a single person’s dedication to environmental action can change entire societies by fostering the social capital necessary for sustainable development.

Recycling as a Diverse Change-Catalyst

A compelling case for recycling as a multifaceted catalyst is crystallized by the story of a man who recycled almost 500,000 cans to purchase a two-bedroom house. It advances a comprehensive model of sustainable living and social empowerment by bridging the environmental, economic, and psychological spheres.

Adopting and institutionalizing such models could reshape routes out of ecological neglect and poverty as global issues intensify, creating resilient communities where environmental preservation and human agency co-create enduring value.