2025 has hit U.S. manufacturing harder than most years in recent memory. Thousands of layoffs swept through cities from Detroit’s auto plants to Dallas’s electronics hubs, shaking communities that have relied on factories for generations.

Since 2000, the nation has lost more than 4.5 million manufacturing jobs—a 26% decline—but this year’s cuts were particularly concentrated across automotive, electronics, and packaging industries. “Automation and global competition have fundamentally changed the landscape,” said Dr. Emily Chen of the Brookings Institution. The losses have left some states struggling far more than others.

Here’s what’s happening in America’s industrial heartland.

Historic Shifts and Industry Hotspots

Manufacturing in the U.S. has been shrinking for decades. Employment peaked at 19.6 million workers in 1979 but had dropped to 12.7 million by 2024. At the same time, production grew, with U.S. manufacturing GDP rising 45% from 2000 to 2024. Factories now produce nearly twice as much per worker thanks to robotics and digital tools, but these gains have come at a human cost.

Some industries were hit especially hard. Electronics manufacturing lost 786,000 jobs since 2000, printing shed 452,000, and apparel fell by 421,000. Only food, beverage, and tobacco manufacturing expanded. Dr. Chen points out that regions that thrived on labor-intensive work now face persistent declines, while states with specialized industries have fared better. These historic shifts show just how uneven America’s manufacturing recovery—or decline—has been.

State-by-State: Where the Losses Hit Hardest

Michigan led all states in job cuts, losing between 3,000 and 5,000 positions. General Motors eliminated 1,200 roles at Detroit’s Factory Zero and paused battery production at Ultium, affecting over 1,000 workers. Stellantis plant shutdowns and Dana Thermal Products’ closure in Auburn Hills compounded the blow. “It’s not just numbers—it’s families and entire communities,” said Detroit resident Marcus Hill, whose brother lost his job at Factory Zero. “We’ve seen this before, but it feels different now with electric vehicles changing everything.”

Pennsylvania lost over 2,500 jobs, with reductions at Boeing, Philips Respironics, and International Paper, as well as closures in metal fabrication and food processing. Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois also saw thousands of cuts, particularly in automotive and food processing. In Illinois, a three-month strike at Boeing’s St. Louis-area facilities affected more than 3,200 machinists. At the same time, Stellantis’s plans for 5,000 new jobs in Belvidere offered a rare bright spot amid the turmoil.

Southern States and Regional Challenges

The South was not spared. Tennessee lost up to 1,500 positions, including temporary halts at GM’s Ultium battery plant in Spring Hill. South Carolina, despite experiencing manufacturing GDP growth, shed roughly 2,500 jobs as automation and offshoring led to the elimination of labor-intensive roles. Texas, Iowa, and New Jersey each lost between 1,000 and 3,000 jobs, with electronics, agriculture, and pharmaceuticals among the hardest-hit sectors.

These regional trends highlight a stark reality: even thriving manufacturing economies are vulnerable to technological and global pressures. The losses are not uniform, but they touch communities large and small, threatening long-standing local industries and forcing workers to adapt quickly or relocate.

The Skills Gap and Unfilled Jobs

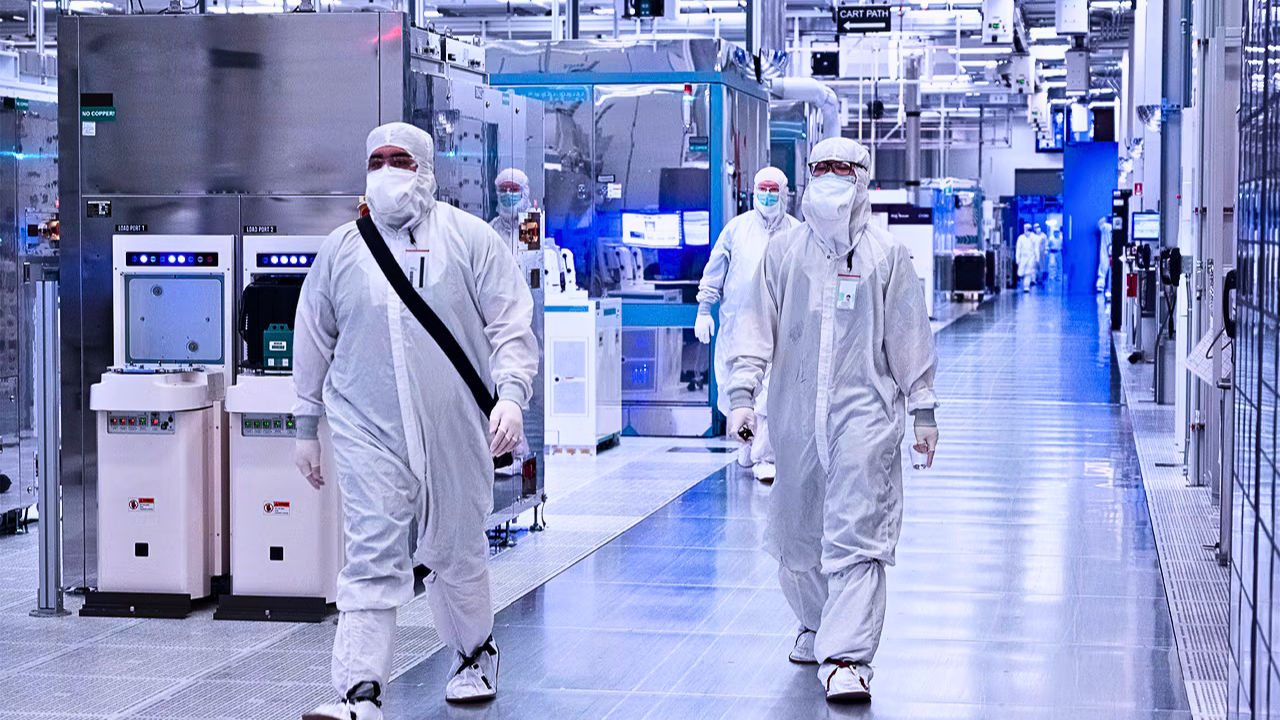

Even as layoffs mount, manufacturers warn of a growing skills gap. By 2030, as many as 2.1 million manufacturing jobs could go unfilled, potentially costing the U.S. $1 trillion in lost output. Retiring Baby Boomers, pandemic aftershocks, and a shortage of technical training have left factories struggling to find workers with expertise in robotics, CNC machining, and data analytics. “Ninety-four percent of executives say the skills gap is a serious problem,” noted Dr. Chen.

Companies are responding with apprenticeships, partnerships with schools, and digital training programs. In Minnesota, local manufacturers and technical colleges launched fast-track programs for displaced workers. John Peterson, a workforce coordinator in Hibbing, Minnesota, emphasized, “We need to make sure people have the skills to compete in today’s factories. Otherwise, these job losses will be even harder to recover from.”

Global Context and the Road Ahead

The U.S. is not alone in facing industrial upheaval. Germany and Japan have also seen manufacturing employment shrink as automation and global supply chains reshape their industries. Some countries have managed smoother transitions by heavily investing in workforce retraining and advanced technologies.

Looking forward, U.S. manufacturing faces an uncertain future. Automation, offshoring, and demographic shifts suggest that factories will continue to produce more with fewer workers. While sectors like food and beverage remain resilient, traditional industrial communities must adapt or risk further decline. Policymakers and industry leaders now confront a clear choice: invest in skills and innovation, or risk leaving millions behind in the next wave of industrial change.