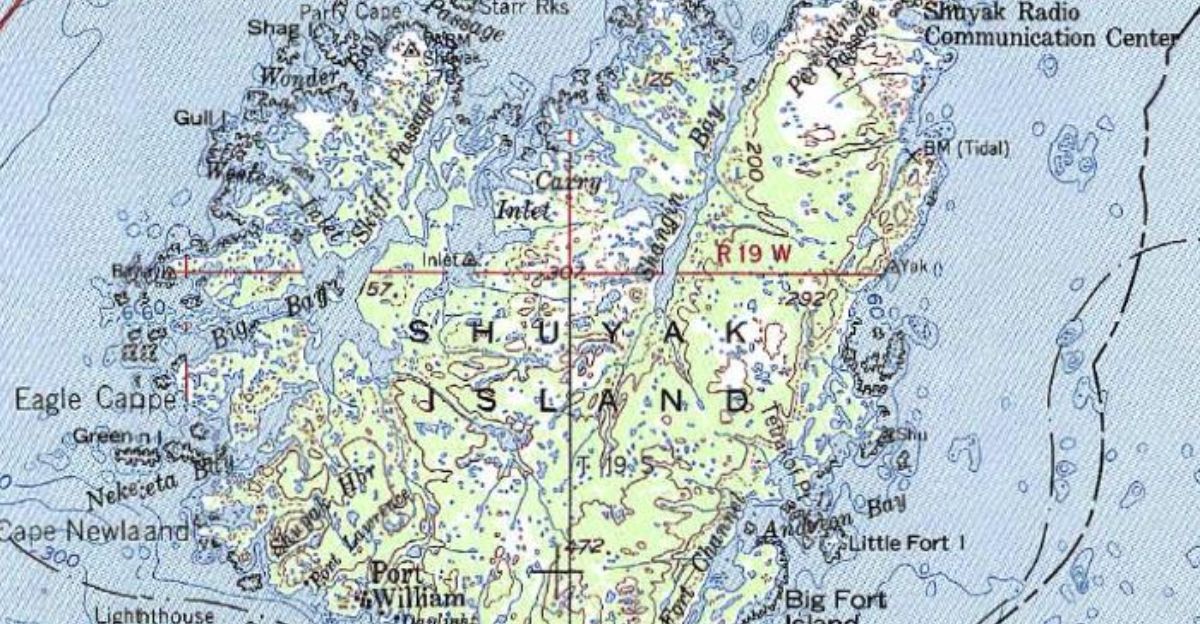

Far from the modern world, Alaska’s remote Shuyak Island has yielded a secret buried for millennia – a 7,000-year-old Arctic village unlike anything seen before. Hidden beneath windswept grass and coastal soil, archaeologists from the Alutiiq Museum uncovered dwellings, tools, and clues that pushed the timeline of life in the far north back centuries.

The find challenges long-held beliefs about who first braved this unforgiving land, how they adapted to its brutal winters, and why their story vanished. Once a thriving community in one of Earth’s harshest frontiers, it lay silent, its history sealed away until now.

A Discovery Born From Disaster

The road to this discovery began in an unlikely place – the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. As part of ongoing environmental surveys, archaeologists returned to Shuyak Island year after year, combing its windswept coastlines and forested hills. The finds were small at first, hints rather than revelations.

But in the spring of 2025, everything changed. From beneath the moss and soil, entire villages emerged. One so ancient, it rewrote the story of Arctic settlement.

Artifacts That Whisper Across Millennia

From beneath windblown grass came stone tools, hearths, and the remains of ancient dwellings, objects untouched for nearly seven millennia. Each artifact carries the weight of a human hand, a moment preserved by the soil. Together, they form the earliest known evidence of continuous habitation on Shuyak Island.

These finds link modern Alaska Native heritage to an unbroken story stretching back thousands of years, reshaping what we know about the first people to thrive here.

The Hidden Homes Beneath the Earth

The largest site revealed 11 house pits, semi-subterranean homes built partially underground and insulated with sod. These were not crude shelters but carefully engineered spaces, designed to trap warmth in an unforgiving climate. Archaeologists estimate the village may have supported 200 to 300 residents, a remarkable number given the island’s isolation.

This was no transient encampment; it was a permanent, organized settlement capable of sustaining life in one of the most challenging environments on Earth.

When the Coastline Rewrites History

Patrick Saltonstall, curator at the Alutiiq Museum, says the findings overturn decades of accepted thought. “You go in thinking one thing, but the archaeology tells a more complex story,” he explained.

Once dismissed as marginal, the eastern coastline is now revealed as a vibrant hub of activity. Here, people built lives deeply tied to the rhythms of land and sea in ways we are only beginning to understand.

A Shore Once Overlooked, Now Revealed

The oldest site lay along Shuyak’s eastern shore, a stretch largely overlooked by earlier research. Yet here, ancient people found everything they needed: abundant marine life, inland resources, and protection from storms. The location suggests not chance, but deep knowledge of survival in the Arctic.

Generations before written history, these settlers understood the island’s bounty and how to harness it, leaving behind a settlement that endured for centuries before vanishing into time.

The Date That Changes Everything

Radiocarbon dating revealed the site’s staggering age – nearly 7,000 years – making it one of the oldest recorded habitations in the Arctic. The find forces archaeologists to redraw migration maps and reconsider how early communities organized themselves in the far north.

Evidence now shows that these were not scattered bands but sophisticated societies, thriving in the Arctic far earlier than previously imagined.

When Oral History Meets Science

In the Alutiiq language, Shuyak is Suu’aq, which translates to “rising out of the water,” according to the Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository. Oral histories passed down for generations tell of ancestors living in the Kodiak Archipelago for at least 7,500 years.

Now, science confirms these traditions, anchoring them in physical evidence. The land holds both memory and proof, connecting present-day Alaska Natives to a lineage that stretches deep into prehistory.

Survival in a Land That Gives Nothing Freely

Life on Shuyak demanded skill and adaptability. Residents fished icy waters, hunted sea mammals, gathered berries, and crafted tools from stone and bone. Their homes, built partially below ground and covered with sod, offered protection from fierce winter storms.

Every aspect of their existence was shaped by the need to survive in a place that gave nothing freely, yet rewarded knowledge and resilience.

The Silence That Followed

By the late 1700s, Shuyak’s villages had fallen silent. The arrival of the Russian fur trade brought upheaval, and by the 19th century, no Native communities remained on the island. For centuries, its story lay hidden beneath grass and moss, the memory of its people preserved only in oral tradition, until archaeologists began to uncover the truth piece by piece.

A Wilderness With a Forgotten Past

The Kodiak Archipelago is dotted with ancient sites, but none match Shuyak’s age or its power to reshape Arctic history. Over time, the island transformed from a thriving Native homeland to a fishing hub and, later, a state park.

Today, visitors see untouched wilderness, but beneath the surface lies evidence of a civilization that once flourished here, its story only now returning to light.

Unearthing the Final Secrets

Archaeologists race against time to unravel Shuyak’s ancient secrets before they are lost forever to wind, rain, and relentless erosion. Each discovery tears back the veil on a saga of fierce survival, brilliant ingenuity, and an unyielding bond to the land, one that began nearly 7,000 years ago and still pulses beneath Alaska’s surface, waiting to reveal its final, haunting truths.