It’s not every day that the entire flight history of a continent gets turned on its head, yet that’s precisely what happened in the deserts of Arizona. A team of Smithsonian paleontologists has uncovered Eotephradactylus mcintireae, now confirmed as North America’s oldest known pterosaur.

Dating back an astonishing 209 million years, this tiny airborne pioneer predates all previously known flying reptiles on the continent, rewriting the timeline of Triassic flight evolution. Unearthed at Petrified Forest National Park, this fossil offers far more than ancient bones; it unlocks fresh mysteries about the dawn of powered flight in a world so distant that it challenges everything we thought we knew.

From Bones to Breakthrough

For years, volunteers and researchers tirelessly sifted through the dense PFV 393 bone bed in northeastern Arizona, hoping for a breakthrough. Then Suzanne McIntire, a dedicated FossiLab volunteer, uncovered a tiny jaw fragment that would rewrite history. Its tightly packed teeth nestled in a delicate lower jaw revealed something extraordinary — not an amphibian or turtle as initially thought, but a previously unknown small pterosaur.

This single find transformed decades of routine fossil sorting into a groundbreaking scientific discovery. McIntire’s unwavering dedication mirrors the remarkable journey of these ancient bones — from forgotten fragments buried in time to a revelation reshaping our understanding of prehistoric flight.

Brick by Brick: Establishing the Age

Pinpointing the age of the fossil demanded a meticulous, multi-layered approach. Scientists applied radiometric dating to the volcanic ash layers surrounding the find, alongside detailed analysis of the stratigraphic context, to confidently date it to approximately 209 million years ago … deep within the late Triassic Norian stage.

Such precision is exceptionally rare; only a handful of early pterosaur fossils worldwide boast such firmly established timelines. Smithsonian paleontologist Ben Kligman hailed the discovery as “a snapshot of a dynamic ecosystem,” offering an extraordinary glimpse into the ancient world where this tiny flyer once soared.

What It Took to Fly: Anatomy Unveiled

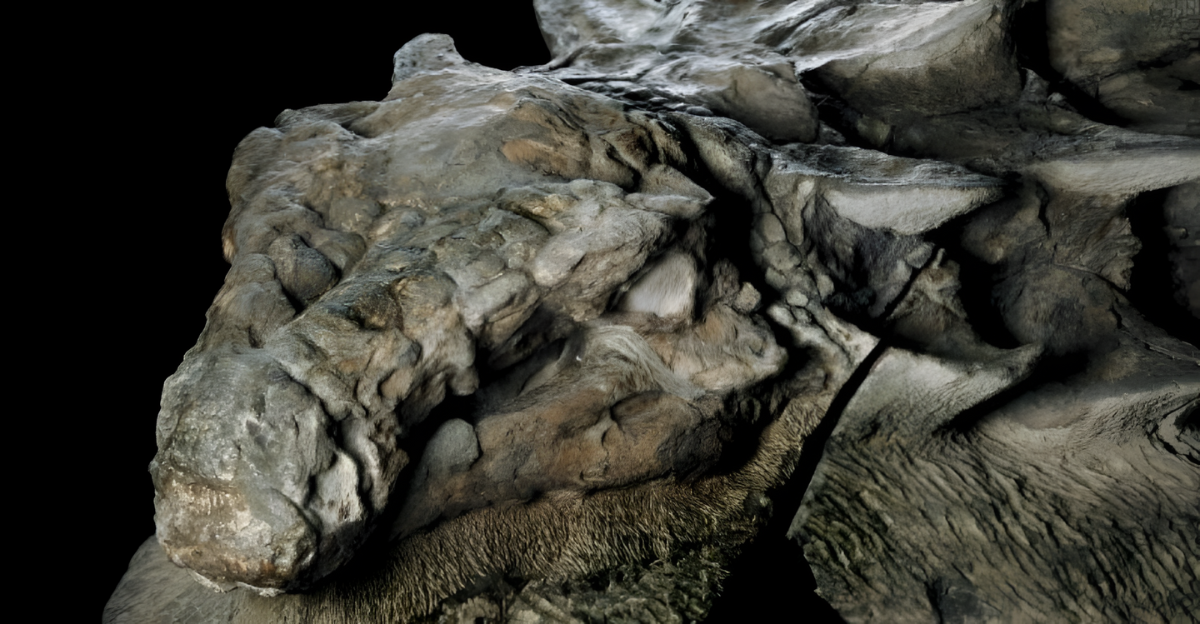

Eotephradactylus mcintireae showcases hallmark pterosaur features: a membrane wing stretched across an elongated fourth finger, hollow bones, and a lightweight frame. Yet the toothy jawbone – heterodont, worn, and elegant in miniaturized form – clinched its identity.

Roughly the size of a small seagull, this early pterosaur appears capable of launching, gliding, and even perching long before birds evolved. The find pushes back the known geographic and ecological reach of prehistoric flight on this continent.

Naming the Ash‑Winged Dawn Goddess

The species name honors the rock and the individual: Eotephradactylus combines Greek for “dawn goddess” and “ash‑winged,” a poetic nod to volcanic ash that preserved the remains. McIntireae recognizes Suzanne McIntire’s consistent fossil prep efforts that brought the jaw to light.

McIntire had spent about 18 years among countless fragments, proving that slow, careful work often yields revolutionary results. The name captures the story of preservation and people.

Why So Rare? Fossilized Flight

Pterosaur bones are incredibly fragile – thin, hollow, and prone to breaking apart. Usually, they crumble long before they can turn into fossils. But at PFV 393, something special happened. Periodic river floods and volcanic ash quickly buried these delicate bones, creating a natural time capsule.

This rare combination of fine flood mud and ash sealed the fragile remains, even preserving tiny teeth. Thanks to this perfect preservation, PFV 393 became a fossilization hotspot – an almost impossible place for such fragile creatures to survive through time.

A Treasure Chest of Triassic Diversity

The PFV 393 bone bed is one of North America’s richest and most diverse late Triassic fossil sites in northeastern Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park. Over the years, scientists have uncovered remains from at least 16 vertebrate species here, including early frogs, turtles, armored reptiles, crocodile-like predators, and even sharks … seven of which are entirely new to science.

This vibrant fossil hotspot isn’t just a collection of isolated bones; it reveals a thriving prehistoric ecosystem. Finding Eotephradactylus among this diverse cast allows paleontologists to piece together how species interacted and coexisted, offering a rare, detailed snapshot of life more than 200 million years ago.

The Detective Work Behind Identification

Smithsonian paleontologist Ben Kligman compares the identification process to flipping through a “mental Rolodex” filled with Triassic-era anatomical clues. Every detail of the jaw – tooth sockets, curvature, wear patterns, and spacing – was scrutinized under a microscope and meticulously compared to those of amphibians, reptiles, and archosaurs.

“By a process of elimination, and recognizing features unique to pterosaurs, it became clear this was no ordinary fossil but a groundbreaking discovery,” Kligman explained. This painstaking detective work highlights the deep expertise and relentless patience required to reclassify a tiny bone and reveal a new branch of prehistoric life.

A World in Ecological Transition

The bone bed vividly captures a transitional moment near the end of the Triassic. Some ancient lineages—like giant amphibians and armored reptiles—still thrived alongside emergent groups such as frogs, turtles, and pterosaurs.

Kligman notes that although dinosaurs existed then, they are absent from this ecosystem, likely due to habitat preferences, emphasising that these smaller vertebrates dominated before dinosaur supremacy. The site captures the direct overlap of old guard and evolutionary newcomers.

Why Precision Dating Matters

Previous North American Triassic pterosaur finds, fragmentary and poorly dated, left significant gaps in evolutionary timelines. By tying Eotephradactylus to a specific ash layer dated to 209 million years, researchers could precisely position it in the early diversification of pterosaurs.

Kligman emphasized that this is the only early pterosaur globally with such tight geological anchoring, making it crucial to map when and how powered flight emerged and spread across Pangaea.

Arizona Then vs. Arizona Now

Back in the Late Triassic, the region now known as Arizona was a lush, river-crossed floodplain near the equator of the supercontinent Pangaea. The climate was tropical and periodically violent, with floods and volcanic ashfalls reshaping the landscape.

That setting fostered vibrant biodiversity, from armored amphibians to early reptiles and Eotephradactylus swooping over ancient waterways. Today’s desert is deceptive, as beneath it lies a buried world of green channels and ash-laden riverbeds.

Size Matters: A Tiny Aeronaut

With a wingspan of roughly one meter, close to the size of a modern seagull, Eotephradactylus mcintireae was a master of precision flight. Unlike the massive Pteranodon that would soar the skies tens of millions of years later, this early pterosaur relied on speed, maneuverability, and sharp turns to survive.

Paleontologists suggest it hunted armored fish, aquatic insects, and small invertebrates along Triassic riverbanks, using keen eyesight and quick wingbeats to snatch prey midair or from the water’s surface. According to Smithsonian researchers, its discovery helps fill a crucial gap in the pterosaur fossil record, revealing that even in their earliest forms, these reptiles had already evolved specialized roles within their ecosystems.

Such ecological diversity so early in their history hints at a rapid evolutionary rise following their first appearance in the Late Triassic.

Fragility Seen as Fortune

Pterosaur bones are so thin and hollow that they seldom persist in the fossil record. Kligman notes how exceptional it is that such slender pieces survived and fossilized intact. Those jaw and wing fragments owe their preservation to the site’s rapid burial and extraordinary chemistry.

In that sense, Eotephradactylus owes its existence in a scientific context to extraordinary geological fortune.

A River Ecosystem Under Pangaea

Arizona lay just above the equator during this period, hosting a mosaic of rivers, wetlands, and floodplains under tropical warmth. Fish, including early sharks, shared the habitat with frogs, turtle precursors, rauisuchians, and phytosaurs. Eotephradactylus likely wheeled through the skies before diving toward rivers and streams to snatch unsuspecting aquatic prey within this thriving web of life.

The late Triassic landscape teemed with evolutionary experimentation, with new species emerging and ancient ones adapting. The PFV 393 fossil bed freezes this dynamic world in its final act, moments before the sweeping extinction events that would redraw Earth’s biological map.

Modern Tools Meet Ancient Bones

The researchers used micro‑CT scanning to study the jaw and teeth without damaging them, revealing fine features like cusp counts, wear grooves, and tooth implantation patterns. These scans confirmed heterodont dentition and heavy wear consistent with a hard‑bodied diet.

This shows how modern imaging gives new life to ancient specimens, allowing discovery even from fragmentary remains. No chisel, no break – digital tools brought clarity where traditional methods might have been too crude.

What Triassic Teeth Reveal

Worn teeth, including multicusped forms in the jaw, hint at diet and feeding methods. Heavy wear patterns suggest Eotephradactylus regularly consumed armored fish or invertebrates with tough exteriors. This tells a bigger story about this pterosaur not being an insectivore but part of freshwater food webs rich enough to support predatory flying reptiles.

Fossil teeth serve as time capsules, allowing paleontologists to reconstruct ancient diets with the same precision that biologists use when examining modern stomach contents.

Volunteers at the Heart of the Find

The Smithsonian’s FossiLab volunteers spend thousands of hours extracting and cleaning minute fossils from sediment blocks. McIntire’s discovery wasn’t heroic in a single moment; it came through years of careful cataloguing alongside professional paleontologists.

As Kligman remarked, “volunteer efforts … brought this jawbone to the attention of paleontologists”, a testament to citizen science and collaborative discovery at its best.

A Snapshot Before Mass Extinction

This fossil assemblage captures the final state of a world just before a major evolutionary reset. Around 201 million years ago, a mass extinction event wiped out many dominant Triassic lineages. Eotephradactylus and its contemporaries lived shortly before that transition.

As Kligman said, the PFV 393 bone bed acts as a “prehistoric time capsule,” documenting what life looked like just before dinosaurs rose to global dominance.

What Lies Ahead in the Badlands

Excavations at Petrified Forest National Park are far from over, and Eotephradactylus may prove to be only the first of many remarkable finds. Ongoing work, from meticulous lab preparation to high‑resolution micro‑imaging and expanded field digs, reveals even more about Triassic biodiversity in North America.

The research team now focuses on smaller vertebrates and species rarely appearing in the fossil record. With each new specimen, they close gaps in evolutionary history, bringing the distant past into ever‑sharper focus.

A New Flight in Paleontology

Eotephradactylus mcintireae doesn’t just add a page to North America’s fossil record; it rewrites an entire chapter on early powered flight, ecological shifts, and the origins of modern vertebrate communities. This seagull‑sized pterosaur, sealed for 209 million years in a blend of volcanic ash and river mud, was brought to light through the persistence of researchers and volunteers.

Its discovery delivers a striking truth … even the smallest fossils can revolutionize science. It’s a vivid reminder that long before birds ruled the skies, Arizona’s horizon was alive with the first daring fliers of prehistory.