As China rebalances its soybean imports away from its historical reliance on U.S. supplies toward South American alternatives, notably Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, the changing global soybean trade scenario in 2025 indicates a significant economic and strategic disruption for the United States.

China’s strategic imperatives to diversify supply sources and increase domestic soybean self-sufficiency, along with the ongoing trade tensions and tariffs resulting from the protracted U.S.-China trade war, are the driving forces behind this decision. South American producers currently account for the majority of China’s soybean imports, which are expected to reach 106.4 million tonnes for the 2024–2025 marketing year, significantly surpassing U.S. exports.

Trade Dynamics in the Past

Historically, the United States has controlled the world market for soybean exports, especially to China, which purchases around 60% of the world’s soybeans. American soybeans were the go-to option for many years, but starting in the middle of the 2010s, growing trade tensions that resulted in retaliatory tariffs changed the situation.

When China levied a 25% tariff on American soybeans in 2018, it was encouraged to look for other suppliers in South America. The main benefit was Brazil, which quickly increased its capacity to produce and export soybeans in order to satisfy China’s enormous demand.

Impact of Tariffs and Trade Tensions

Soybean flows were significantly impacted by trade politics. By 2025, China’s import duty on U.S. soybeans, including VAT and MFN taxes, increased to about 34% due to tariffs triggered by the U.S.-China trade war. With billions of dollars in lost sales and a decline in demand for American soybeans in the most significant buyer market in the world, the economic impact on American farmers is severe.

Notably, American soybean shipments to China fell sharply in the first half of 2025, accounting for only around 25% of China’s imports, compared to a majority share in previous years. American producers were forced to look for other markets, including Egypt, Mexico, and some parts of Asia, as a result of this tariff-induced trade barrier, but these markets are unable to match China’s volume or prices.

Supply Surge in South America

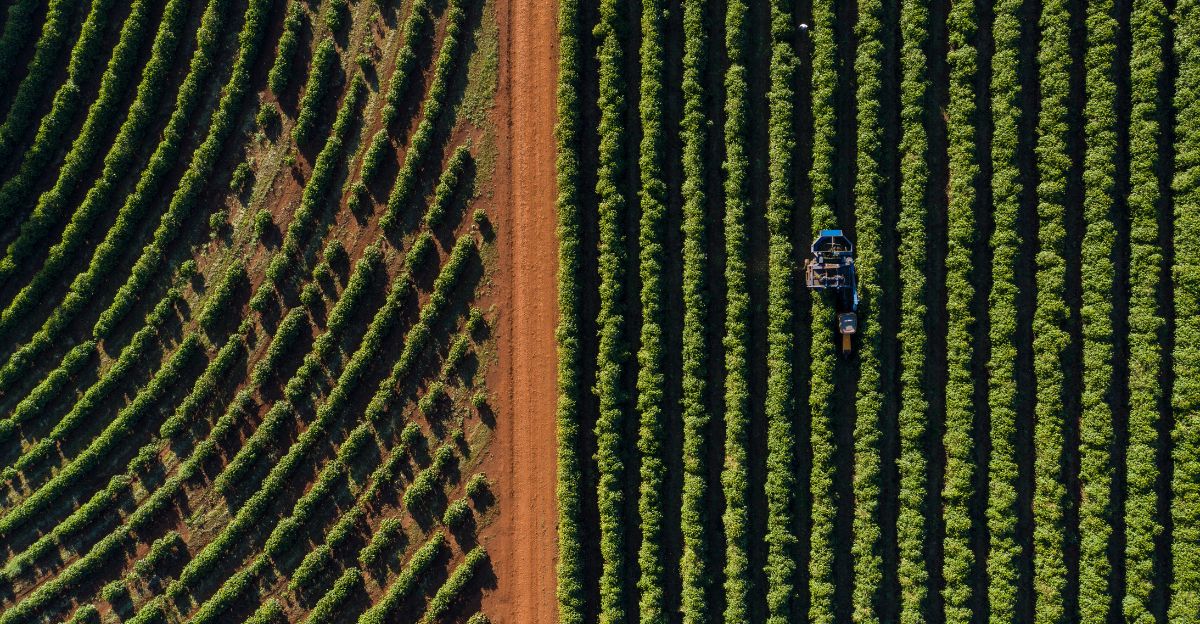

South American nations, primarily Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, responded by rapidly increasing their soybean exports to China. Brazil reached a record high in 2025 when its soybean exports to China reached over 10 million tonnes per month in July, accounting for almost 90% of China’s soybean imports in that month alone.

Brazil’s established position as China’s go-to source for soybeans is highlighted by this increase. Higher commodity prices and increased agricultural export earnings are part of these nations’ economic windfall, which motivates significant investments in infrastructure and production efficiency. An emerging agricultural superpower shift is depicted by this market capture amidst geopolitical tensions, in which South America takes advantage of trade disruptions in the United States to strengthen its economic ties with China.

The Strategic Diversification of China

China’s shift to South American soybeans is a strategic diversification based on longer-term economic planning, not just a response to tariffs. China’s Five-Year Agricultural Plan through 2027 calls for expanding domestic soybean production, decreasing dependency on U.S. commodities, and enhancing food security through diversified supply chains.

This strategic change ensures resilience against geopolitical threats and trade disruptions. Furthermore, China’s consumption patterns are changing; domestic policies aim to balance imports with increasing domestic production, while rising demand for edible oils and animal protein drives soybean import volumes. This two-pronged strategy simultaneously challenges American export leadership and promotes sustainable long-term imports from preferred South American partners.

Economic Toll on U.S. Agriculture

The economic consequences for U.S. farmers are profound and enduring. Missing out on China’s soybean market leads to billions in lost revenue annually, eroding farm income and jeopardizing rural livelihoods. The U.S. faces reduced market prices due to surplus inventories and must rely on less lucrative or smaller alternative markets. This shift not only impacts farmers but also the supply chain encompassing processors, exporters, and rural communities dependent on soybean-related commerce.

Furthermore, diminished export volumes undermine U.S. negotiating power in global agricultural trade and reduce the geopolitical leverage that soybean export dominance once conferred, representing a multi-layered economic and political setback.

Social and Environmental Aspects

There are also complex social and environmental repercussions to this change in bilateral trade. Due to land clearing and agricultural expansion, Brazil’s soybean boom, which is driven by China’s demand, puts further strain on the Amazon rainforest and other delicate ecosystems. Degradation of the environment puts biodiversity loss and the effects of the global climate at risk.

On the other hand, U.S. producers are more vulnerable to economic strain and the dangers of rural depopulation, which could drive some smaller farms out of business. Thus, trade-driven changes in agriculture trigger intricate ecological and demographic changes across continents, raising the stakes beyond economics to include social cohesion and environmental sustainability.

Psychological and Strategic Implications

From a strategic psychology perspective, the trade disruptions trigger cognitive and emotional stress across U.S. farming communities, eroding trust in government policy efficacy and global trade reliability. These economic uncertainties promote risk-averse behaviors, less innovation investment, and a sense of marginalization among farmers reliant on exports.

On the international stage, China’s diversification recalibrates power dynamics, signaling to other importers the vulnerability of overreliance on a single supplier amid geopolitical tensions. This shift fosters a more multipolar global trade system with distributed risks, which may recalibrate global alliances and agricultural diplomacy for decades.

Solutions and Strategic Responses

To counteract these losses, the U.S. must diversify its export markets aggressively and innovate in soybean cultivar development, value-added processing, and sustainable practices to regain a competitive advantage. Policymakers should pursue trade dialogues to reduce tariffs and barriers while investing in rural economic resilience and supply chain modernization. Alternative markets in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America represent critical growth areas.

Domestically, increasing soybean yields and exploring biofuel and industrial applications could expand demand. Strategic government coordination around agricultural diplomacy is crucial to reclaiming market share and rebuilding lost trust in vital export partners.

Opportunity in Crisis

Though framed as a setback, the China shift could catalyze an overdue agricultural renaissance in the U.S., pushing farmers and policymakers toward sustainability, diversification, and innovation. Reduced dependency on China forces exploration of new crops, niche markets, and resilient farming systems, which are less vulnerable to geopolitical volatility.

This crisis can drive ecosystem-friendly practices, agro-tech adoption, and domestic market expansion, rebalancing rural economies for the 21st century.

The Evolution of Agriculture in Brazil

Brazil’s boom in soybean exports provides a powerful example of how nations take advantage of geopolitical divisions. In order to establish itself as China’s main supplier of soybeans, Brazil made significant investments in technology, transportation, and credit systems over the course of two decades, transforming its agricultural infrastructure.

This change was persistent and strategic, taking advantage of the tariff dispute between the United States and China. Brazil’s capacity to increase production while effectively handling export logistics is a stark reminder to American producers not to become complacent, as it demonstrates how trade diplomacy and competitive agility can quickly realign global commodity flows.

Speculative Future Situations

In the future, a prolonged trade stalemate between the United States and China may solidify South America’s hegemony in soybean exports, forcing the United States to either innovate or give up more ground. A sudden normalization of trade relations, on the other hand, might permit a partial recovery of the U.S. market, but with a permanently reduced share because of new supply chains that have become ingrained.

Increased Chinese investment in South American agriculture is another hypothetical effect that might have an impact on the world’s food supply by forming a new geopolitical bloc. However, U.S. farmers may choose to bioengineer soy varieties with new characteristics that appeal to non-Chinese consumers, launching a new era in agriculture.

Unexpected Data Findings

According to recent data, China imported 12.2 million tonnes of soybeans in August 2025 alone, setting a record. The majority of these imports came from Brazil, giving China supply security and generating surplus beyond immediate consumption needs. Because China can maintain a surplus buffer, it can withstand global shocks and trade barriers without suffering immediate harm, undermining U.S. leverage.

In contrast, American soybean exports to China have decreased to less than 4% of monthly imports in specific 2025 periods, indicating a sharp decline in market share in real time. This information demonstrates how quickly changes in trade policy and geopolitics can significantly impact commodity markets.

Ag and Tech Markets

The interaction between geopolitics and advanced agri-tech is an unusual viewpoint to take into account. China’s interest in Brazil’s soybeans encourages investments in South American agricultural technology, such as drone surveillance, precision farming, and biotech advancements, hastening Brazil’s agricultural modernization.

At the same time, American ag-tech companies are under pressure to innovate faster in order to recover their competitive edge through supply chain transparency through blockchain verification and yield enhancements. Global agricultural power may be redefined beyond conventional production metrics toward tech-savvy, data-driven farming supremacy as a result of this technological race associated with geopolitical trade shifts.

In Conclusion

The multibillion-dollar damage to U.S. soybean exports caused by China purchasing from rivals is more than just a financial setback; it represents a complicated realignment of global agricultural trade, geopolitical influence, and strategic diplomacy. The longer-term environment necessitates strategic adaptation, diversification, and innovation, even as American farmers experience immediate financial hardship and market displacement.

China’s skillful manipulation of South American suppliers demonstrates how trade wars and economic nationalism alter commodity flows, establish new agricultural power centers, and shape narratives around global food security. Policymakers, producers, and other international stakeholders who want to predict and address trade disruptions in the twenty-first century effectively must have a thorough understanding of these dynamics.