Pacific sea surface readings in 2025 hinted at change under the radar. After months of ENSO-neutral (neither El Niño nor La Niña) signals, oceanographers now note a broad cooling pulse in the central Pacific.

Underwater thermometers show a layer of colder-than-average water extending 200 meters deep. Such subsurface chill often foreshadows atmospheric shifts weeks later.

Federal meteorologists are watching these trends closely: if that cold water reaches the surface, it could dramatically alter America’s winter storm patterns. For now, the full impact remains hidden, but the alarm has quietly been sounded.

Rising Stakes

Western states already face a dire summer-long drought, creating a high-pressure backdrop. Nearly 80% of the Pacific Northwest is in drought, with over half classified as severe or extreme.

States from Oregon to California have declared emergencies; Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek has ordered aid efforts in multiple counties.

Farmers already saw heavy crop losses, and reservoirs are low. As a result, every forecast now carries huge weight: a snowy winter could bring relief, but another dry season would deepen the crisis. Water managers and farmers alike are bracing for either outcome, knowing the stakes are far higher than usual.

Historical Context

La Niña – Spanish for “little girl” – is the cool phase of the Pacific’s El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle. It occurs roughly every 3–5 years.

During La Niña, trade winds strengthen, pushing warm surface water west and letting cold deep water rise off the Americas. This shifts global weather patterns: northern rain belts can get wetter, while the southern U.S. often turns drier.

Historical La Niñas have ranged from mild dips to major multi-year runs. For example, the “triple-dip” La Niña of 2020–2023 spanned three winters, helping dump record snows in some mountains while fueling years-long droughts in other regions.

Mounting Pressures

Even as ENSO stayed officially “neutral” through late summer, signs of change grew. NOAA reports that Pacific surface temperatures were near average, but crucially, below-normal heat was building deep below the surface.

In August, cooler-than-average water was observed across the central equatorial Pacific down to 200 meters. Ocean scientists note that such extensive subsurface cooling often foreshadows a La Niña onset.

The unseen chill now rising in the Pacific could soon force atmospheric shifts. Forecasters say we may only be weeks away from seeing the surface reflect these deep ocean changes.

The 71% Revelation

A formal forecast shift arrived on Sept. 11. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center issued a La Niña Watch, assigning a 71% probability for La Niña this fall. That was a dramatic leap from earlier outlooks – the highest confidence NOAA has had since the recent multi-year La Niña stretch.

“This is a significant shift, especially in the near term,” said CPC scientist Michelle L’Heureux.

Her remark captured the surprise: models and observations snapped quickly into sync. The forecast now stands dramatically different than it did just weeks before, signaling rapid climate re-alignment that has set off alarms from Sacramento to Seattle.

Regional Battleground

La Niña’s return sets up a weather tug-of-war across the West. Washington and Oregon – fresh off one of their driest years – could finally see heavy rain and snow, whereas the desert Southwest risks even more aridity.

Seasonal precipitation outlooks show above-normal snowfall chances for the Pacific Northwest and continued drought odds in California and the Colorado basin.

In terms, La Niña often drives Pacific storms farther north: mountain states and the northern Rockies get wetter weather, while the southern tier stays dry. Growers, forest managers and water suppliers in both zones are watching forecasts intently – each hoping their side of the forecast wins out.

Human Stories

Across the drought-stricken West, people are watching these forecasts with a mix of hope and anxiety. “We’re crossing our fingers, hoping for the rain to come,” said Oregon State Climatologist Larry O’Neill.

Washington climatologist Karin Bumbaco echoed the sentiment, cautiously noting that a La Niña forecast makes her “a little more optimistic” about winter precipitation.

Their cautious optimism reflects sentiments in dry farming communities and reservoir towns: years of water restrictions and farm losses have left residents desperate for normal rainfall. One east-side rancher sighed that “every snowflake is precious now,” underscoring how much is riding on this one winter.

Scientific Consensus

Behind the scenes, climate experts are unusually aligned on what’s coming. Every major forecast model now tilts toward Pacific cooling, and agencies from NOAA to international centers are on the same page: La Niña seems likely.

Leading climatologists note that even a weak La Niña can have outsized impacts. For instance, Columbia University’s Richard Seager points out that slight shifts in the jet stream or ocean currents could greatly change where storms go.

Another researcher emphasizes that La Niña events can influence hurricane seasons and global rainfall patterns. In short, the scientific community broadly agrees: we are likely transitioning out of neutral, even if uncertainties remain about intensity.

Macro Implications

This potential shift ends the longest ENSO-neutral span since 2019 and could change global weather in 2026. The World Meteorological Organization reports about a 60% chance of La Niña this Oct–Dec, mirroring U.S. projections.

North American outlooks match European and Australian models: most predict a cooling tropical Pacific. If these forecasts pan out, they could alter patterns worldwide – for example, a drier southern U.S. and wetter northern U.S. in winter, and shifts in monsoon or tropical cyclone behavior globally.

With many nations’ climate offices sounding similar alarms, it’s a synchronous alert: the Pacific is poised for broader change.

The Weakness Factor

There is a catch: this La Niña is forecast to be comparatively mild and brief. By mid-winter, NOAA’s outlook shows the chance dropping to roughly 54% for Dec–Feb.

Models expect the signal to fade after a few months. Experts warn that a “weaker La Niña” may not bring classic impacts everywhere. As one forecast put it, “A weaker La Niña implies it would be less likely to result in conventional winter impacts…”.

This means some areas might not get as much rain or snow as typical La Niña patterns would suggest. Western planners are thus preparing for a mixed bag: La Niña-like storms might materialize, but perhaps not with textbook consistency.

Agricultural Tensions

For farmers, the uncertainty is exasperating. Central Valley growers facing a 35% irrigation allocation debate whether to plant winter crops now or wait for rains that may never come. California fruit and nut producers watch forecasts while already factoring in the cost of fallow fields and costly feed.

In the Colorado River states, ranchers worry: without winter storms, pastures will remain parched and hay prices will skyrocket. Local water boards have spent the summer weighing each new forecast, but the need for water rights and schedules makes changes difficult. In short,

Every weather update feeds into a high-stakes gamble: planting decisions, water trades, and even livestock sales hinge on what falls from the sky next.

Strategic Pivots

Water managers are already shifting tactics based on the outlook. California’s Department of Water Resources has ramped up reservoir surveillance and modeling as snow and rain prospects evolve. Officials say they are drafting contingency plans for both prolonged drought and flood scenarios.

Similarly, Colorado River negotiators are discussing how to adjust releases if La Niña brings floods or maintains scarcity.

Some state governors and agencies are considering temporary water transfers, new conservation programs, or even expedited infrastructure projects. Essentially, the forecast is prompting a hedge: officials across the West are preparing multiple plans so that, whether it rains or not, they’ll have a strategy.

Recovery Attempts

This year’s drought declarations have already triggered unprecedented conservation drives. Cities have tightened outdoor watering rules, and farmers have fallowed fields at record levels. States poured money into new canals, groundwater recharge wells, and ditch linings.

Yet experts caution that even a successful La Niña winter won’t immediately undo years of deficit. Western reservoirs and aquifers were drained over the last half-decade, and replenishing them fully will take time.

Some hydrologists estimate that it could require back-to-back wet winters just to break even. In short, recovery — like the drought — will be a multiyear project, with 2026 likely the earliest hopes for lasting relief.

Expert Caution

Despite the optimistic turn in forecasts, many scientists urge restraint. Dr. Raghu Murtugudde (UMD) reminds us that weak La Niñas often have patchy, unpredictable effects. Stanford researchers also warn that climate change may be altering ENSO’s behavior, so past patterns could shift. In practice,

This means we might see weather unlike any we’ve seen in historical La Niñas. Forecasters stress that no prediction is certain: even with a 71% chance, every model and forecast comes with a sizable margin of error.

The message is: stay prepared, but don’t assume everything will change overnight.

The Waiting Game

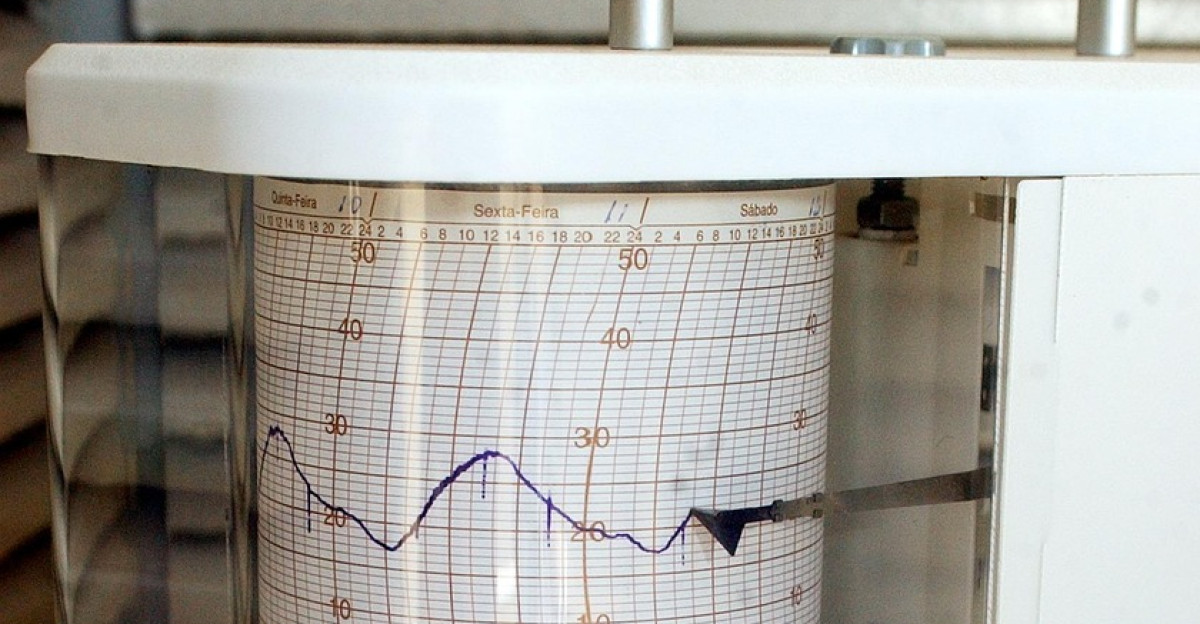

With fall underway, scientists will test the forecast by watching the Pacific. To officially confirm La Niña, ocean buoys must record sea surface temperatures at least 0.5°C below average for three consecutive months.

NOAA actually defines a La Niña when the three-month Niño3.4 index is below — 0.5°C for several overlapping seasonsdrought.gov. Early October’s readings will be critical.

If cool anomalies hold up, the climate community may declare La Niña at the next ENSO report. If not, the forecast could fizzle. In either case, researchers agree that this autumn’s measurements will mark a pivotal test of their seasonal predictions.

Policy Ramifications

The stakes extend to Capitol Hill. If La Niña underdelivers and drought deepens, new federal drought declarations may sweep the West, unlocking emergency aid for farmers and communities.

Congress is already hearing from embattled ag districts pushing for relief. Meanwhile, states are preparing legal defenses over water rights: tribal, urban and agricultural users could clash in court if demand worsens.

The administration faces pressure to fast-track water storage and conveyance projects. In short, political leaders are placing big bets on a forecast whose outcome could trigger billions in spending and policy shifts nationwide.

Global Ripples

Even global markets have taken notice. U.S. wheat and corn futures in Chicago jumped on the La Niña outlook, as traders priced in possible crop shortfalls. Farther afield, Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology sees parallel trends: some climate models there now show Pacific temperatures dipping toward La Niña levels as their spring arrives.

If both hemispheres cool together, world food production could be squeezed.

Grain exporters, shipping companies, and food buyers globally are watching for regional outcomes that could affect prices and supply chains. The synchronized Pacific cool-down means weather in the U.S. could influence harvests from Kansas to Karnataka.

Environmental Stakes

Environmental agencies are preparing too. In the Colorado River basin, wildlife refuges are calculating water deliveries for wetlands and endangered fish based on the new forecasts. Conservationists worry that any additional water will be diverted to farms and cities first, threatening habitat.

Endangered species recovery plans — from razorback suckers to riparian songbirds — could face setbacks if the winter is dry. On the other hand, a wet La Niña might cause flooding that damages some ecosystems.

Either way, legal battles over water in the West look poised to intensify, potentially redefining environmental water rights in the years ahead.

Cultural Shifts

Indigenous leaders in the Southwest report an unprecedented demand for traditional knowledge. Agencies like the Bureau of Reclamation are reaching out to tribes to learn about native weather lore and land management practices.

This surge in consultation underscores a growing respect: tribes’ long-term observations are being seen as vital intelligence. “Our ancestors knew these waters,” one tribal elder recently told a reporter.

This new collaboration could have a lasting impact, blending ancient wisdom with modern science. Regardless of how the winter unfolds, these partnerships may offer lessons that span well beyond a single rainy season.

Future Framework

Taken together, this La Niña forecast could mark a turning point in climate forecasting. If the 71% prediction proves accurate, it would boost confidence in seasonal outlooks and reshape planning in agriculture, infrastructure, and disaster preparation.

Conversely, if the forecast fails, public trust in long-range predictions could falter. As WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo notes, accurate seasonal forecasts translate into “millions of dollars of economic savings” and have even saved lives.

In that sense, how this winter plays out will influence trust in climate science for decades, far beyond the next snowfall or rainstorm.