For much of the twentieth century, a prevailing view in marine biology held that most major marine groups originated in sunlit, shallow waters and later colonized the deep sea. This perspective strongly influenced evolutionary thinking, conservation priorities, and exploration strategies. In May 2014, work on rocks uplifted in the Austrian Alps provided crucial evidence that complicates this narrative.

An international team including Ben Thuy of the National Museum of Natural History in Luxembourg documented nearly 2,500 fossils from Early Jurassic deep-sea deposits (about 180 million years old) near Glasenbach Gorge, some of which are the oldest known representatives of modern deep-sea groups. Their analysis indicates that in situ diversification in the deep sea contributed substantially to modern biodiversity: some lineages did not simply migrate downward from shallow refuges but originated and persisted in dark, deep-water settings for tens of millions of years.

Why Evidence Was Misleading

Before this work, most fossil data for marine animals came from shallow-water deposits, because old deep-sea crust is generally lost to subduction, taking much of its fossil record with it.

This preservation bias helped support the idea that deep-sea faunas were mainly “evolutionary refugees” that had colonized depth from the continental shelf, a pattern known as onshore–offshore diversification. Because very old deep-sea assemblages were almost unknown, the scarcity of ancient deep-sea fossils was often interpreted as evidence that such communities did not yet exist, rather than as a sampling problem. The Glasenbach material undermined the notion that the onshore–offshore model was a universal rule, showing instead that deep-sea lineages with modern affinities already existed by the Early Jurassic.

Uplifted Seafloor and Jurassic Deep Waters

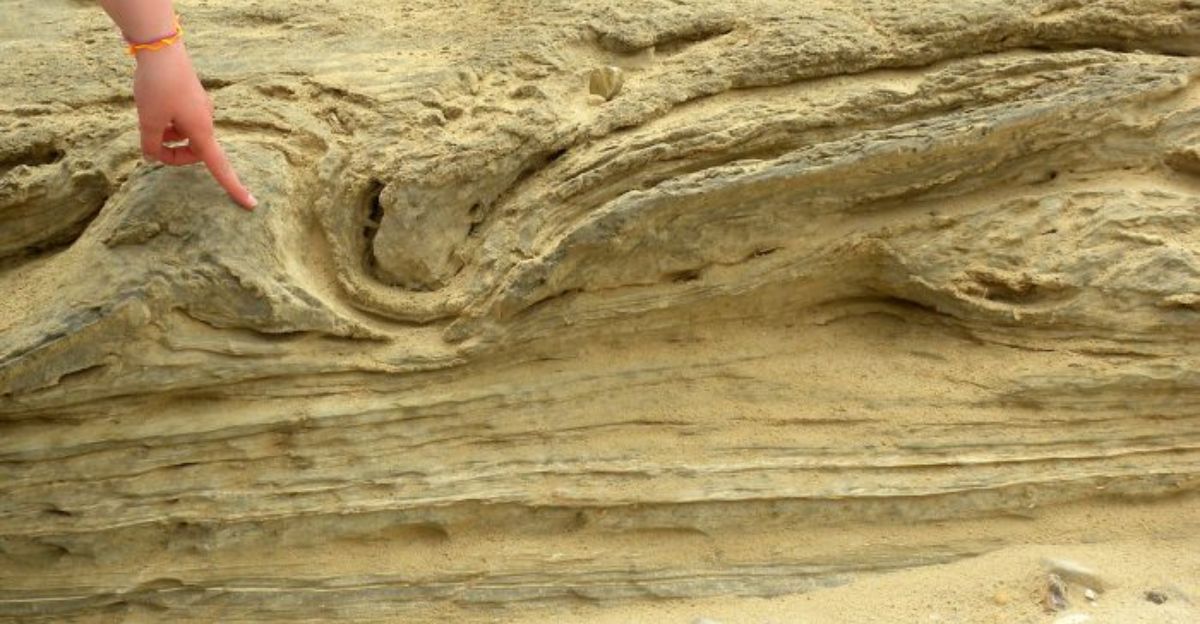

Plate tectonics provided access to this ancient deep-sea ecosystem: seafloor sediments were later uplifted during Alpine mountain building, exposing fossil-bearing rocks that had originally accumulated in deep water.

The Glasenbach assemblage includes at least dozens of species of echinoderms (such as sea stars and sea urchins), gastropods, brachiopods, and ostracods, associated with rock types and faunal composition consistent with bathyal conditions. Stratigraphic and biostratigraphic data place these deposits in the Early Jurassic, around 180 million years ago. Several of the taxa represent the earliest fossil occurrences of families or superfamilies that are still typical of modern deep-sea faunas, providing direct fossil evidence for ancient deep-sea communities rather than mixed shallow-water material.

Deep vs. Shallow Through Time

The researchers compared the Glasenbach deep-sea assemblage with coeval Early Jurassic shelf (shallow-water) faunas. For some groups, especially echinoderms and probably brachiopods, they found that more extant families or superfamilies have persisted in the deep-sea setting since the Early Jurassic than in corresponding shallow-water habitats, implying greater long-term continuity in depth preference at depth.

This does not mean deep-sea diversity always exceeded shallow-water diversity in raw species counts, but it does suggest that the deep sea has been an important long-term reservoir and source of higher-level diversity. The results support a scenario in which deep-sea environments can generate and maintain lineages that later expand onto continental shelves, complicating the idea that shallow waters are always the primary cradle of marine evolution.

Extinction and Environmental Stability

Analyses of the depth preferences of surviving groups show that more deep-sea echinoderm families and superfamilies retained their Early Jurassic deep-water distribution into the present than did coeval shallow-water groups retain their original shallow distribution.

This pattern is consistent with the idea that the deep sea’s relatively stable physical conditions—low temperature variability, muted light changes, and buffered chemistry—can reduce turnover compared with more environmentally variable shallow seas. However, the study cautions that similar percentages of extinct taxa occur in both settings, and that resilience inferred over geological timescales does not translate directly into resistance to rapid, human-driven disturbance.

Deep-Sea Origins in Multiple Lineages

Glasenbach is part of a broader body of evidence suggesting frequent deep-to-shallow evolutionary trajectories. Phylogenetic analyses of stylasterid corals show that this group originated and diversified in deep water, with at least three independent invasions into tropical shallow waters and one into temperate shallow waters; ancestral-state reconstructions recover a deep-water ancestor with probabilities above 0.96.

These molecular results align with fossil data indicating an early deep-water history for stylasterids. Similar deep-sea ancestry followed by later shallow-water expansion has been reported for other groups in separate studies, reinforcing that the classic onshore–offshore pattern is not universal and that deep-sea origins are more common than once assumed.

Rethinking Deep-Sea Conservation

These findings have direct implications for how society evaluates industrial use of the deep ocean. If deep-sea habitats can act as long-term sources and reservoirs of higher-level biodiversity that take millions of years to assemble, then disturbance from activities such as bottom trawling and mining could remove lineages or habitat structures that are not easily replaced.

The authors of the Glasenbach study emphasize that geological resilience and the ability to persist through past natural perturbations should not be interpreted as robustness to rapid anthropogenic change. Emerging stressors including climate-driven oxygen changes, warming, and potential mining-related impacts could severely affect communities adapted to relatively stable conditions over deep time.

Filling the Deep-Sea Data Gap

The Glasenbach fossils highlight how gaps in the deep-sea fossil record have shaped evolutionary theory. Because most of the deep ocean floor is young and older deep-sea sediments are sparse, many macroevolutionary models were built on data dominated by shallow-water deposits, leaving deep-sea dynamics underrepresented.

As more uplifted or otherwise accessible deep-marine strata are studied and molecular phylogenetics continues to refine relationships and ancestral habitats, additional revisions to long-standing views of marine evolution are likely. Given that the deep sea covers most of Earth’s surface and harbors a large fraction of marine biomass, clarifying its role as both a generator and a reservoir of biodiversity will be central to a more complete understanding of life’s history in the oceans.

Sources:

- “First glimpse into Lower Jurassic deep-sea biodiversity” – PLOS ONE (Public Library of Science).

- “Ancient Origin of the Modern Deep-Sea Fauna” – PLOS ONE (Public Library of Science).

- “Multiple Origins of Shallow-Water Corals from Deep-Sea Ancestors” – PLOS ONE (Public Library of Science).

- “Fossil discovery in Alps challenges theory that all deep sea fauna evolved from shallow water ancestors” – Phys.org.

- “Jurassic Fossils Suggest Deep-Sea Origins of Marine Life” – Scientific American.

- “180-Million-Year-Old Fossils Discovered in Deep Austrian Sea” – International Business Times.