A single dawn gunshot in the grey moat of Vincennes fortress ended the life of a Bourbon prince—and detonated one of history’s most quoted political verdicts: “It was worse than a crime; it was a blunder.”

This 1804 execution helped unite Europe’s monarchs against Napoleon and still warns how one decision can redraw the political map.

A reader-driven hunt for the greatest political errors

British columnist John Rentoul invited readers to nominate the “greatest political errors of all time,” turning social media suggestions into a curated top ten.

The final list spans nearly a millennium, from 1066 to 2010, and blends military, diplomatic, and domestic misjudgments, each illustrating how apparently rational choices can unleash far‑reaching and unintended consequences.

A list stretching from Hastings to modern Westminster

Rentoul’s ranking, published in The Independent, runs from King Harold Godwinson’s fatal haste before the Battle of Hastings to Ed Miliband’s narrow victory over his brother David for Labour leader.

Each entry captures a moment when leaders misread risk, underestimated opponents, or misjudged public mood, with outcomes that permanently altered national or international politics.

1. Harold’s exhausting march before the Battle of Hastings

In 1066, Harold Godwinson had just defeated a Norwegian invasion at Stamford Bridge when he marched his army south to confront William of Normandy.

He pushed already exhausted troops roughly the length of England in less than three weeks. Many historians argue that fatigue and limited reinforcements weakened his forces before the decisive Battle of Hastings.

2. Ship Money and the road to civil war

In 1636, Charles I extended “Ship Money,” a levy historically linked to naval defence and coastal towns, into a broader tax imposed without parliamentary consent. For critics, this became emblematic of royal autocracy and constitutional disregard.

The controversy deepened mistrust between crown and parliament, feeding tensions that helped push England toward civil war and the king’s eventual downfall.

3. The Treaty of London that pulled Britain into World War

Another entry is Britain’s decision to sign the 1839 Treaty of London, guaranteeing Belgian neutrality. When Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914, this commitment was central to Britain’s decision to enter the First World War.

The pledge, intended to stabilise Europe, instead helped draw Britain into a conflict that produced immense casualties and long‑lasting political trauma.

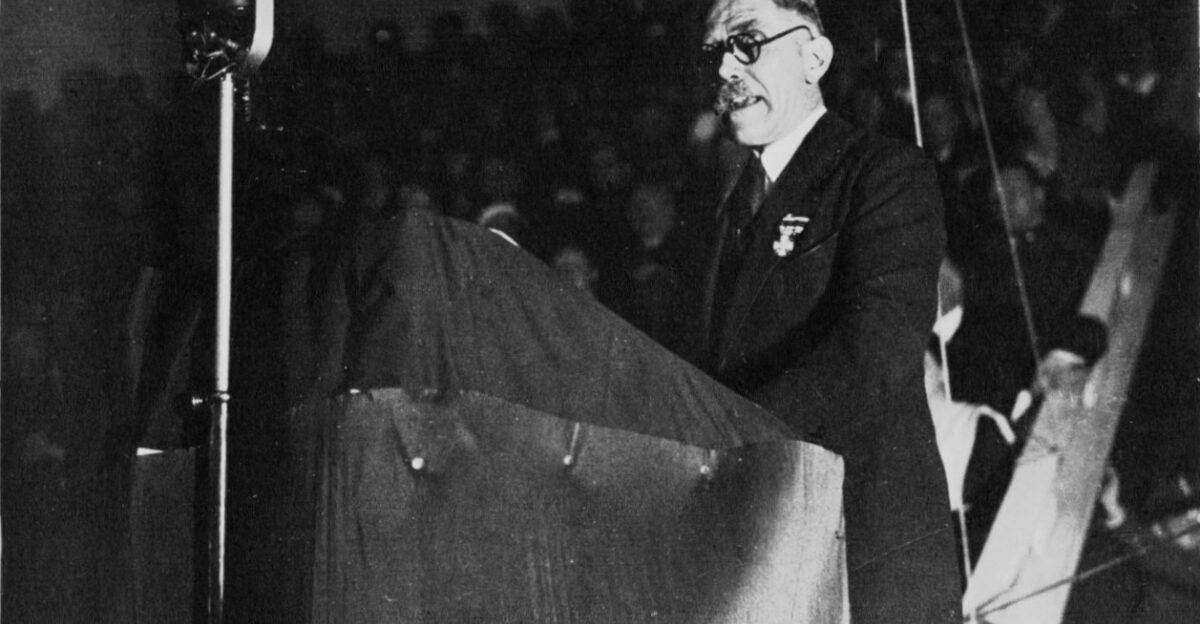

4. Von Papen’s fatal belief that he could control Hitler

In 1933, conservative politician Franz von Papen supported appointing Adolf Hitler as German chancellor, believing a cabinet dominated by non‑Nazis could restrain him. Within months, Hitler sidelined his supposed handlers, neutralised parliamentary opposition, and built a dictatorship.

Historians routinely cite von Papen’s miscalculation as a classic example of elites thinking they can “manage” extremist leaders—and being proved disastrously wrong.

5. Britain’s jet engines that helped power Soviet MiGs

Perhaps the most surprising case is Clement Attlee’s post‑war government authorising exports of Rolls‑Royce Nene and Derwent jet engines, plus technical data, to the Soviet Union in 1946 and 1947.

Soviet engineers reverse‑engineered the designs, feeding into development of the MiG‑15, one of the first successful swept‑wing jet fighters that would later challenge Western aircraft in the skies over Korea.

6. How the Nene decision changed the balance in the air

By the early 1950s, MiG‑15s powered by derivatives of the Nene engine were fighting United Nations aircraft in Korea, creating serious problems for slower, earlier‑generation jets.

Aviation historians argue that access to British turbojet technology accelerated Soviet fighter development, giving Moscow an unexpected advantage at a critical moment in the early Cold War and illustrating the strategic risk of short‑term export decisions.

When secrecy turns into self‑sabotage

Modern politics is full of examples where tools designed for control or record‑keeping end up exposing leaders’ own misjudgments. Hidden recordings, confidential memos, and private messages can all become evidence when public scrutiny intensifies.

The broader lesson echoed by historians is that attempts to manage information from behind closed doors often amplify, rather than contain, the eventual fallout when mistakes surface.

Elections misread rather than mistimed

Not every electoral error is about the date of a vote. Analysts often point to leaders who call elections with misplaced confidence, misreading opinion polls or the depth of public frustration.

In such cases, the blunder lies less in the timing and more in the failure to understand shifting expectations—reminding governments that voter sentiment can move faster than party strategies adapt.

Underestimating public demands for a voice

Across many democracies, pressure has grown for direct public input on big constitutional or international questions. When leaders appear to sidestep that demand—whether on treaties, autonomy arrangements, or major reforms—they risk fuelling long‑term resentment.

Commentators warn that even legally sound decisions can backfire politically if citizens feel crucial changes were made without a clear, visible mandate.

Party choices that reshape national politics

Leadership contests and internal rule changes may seem like domestic party business, yet they often have national consequences.

Choosing a leader whose message, style, or coalition‑building skills do not match the wider electorate can shape opposition strategies, coalition options, and future policy debates. Strategists note that what happens inside parties rarely stays there; it frequently defines the broader political landscape.

The political errors Rentoul chose not to include

Rentoul acknowledges several popular suggestions that he ultimately excluded. These include Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasing Hitler, the decision to hold the 2016 Brexit referendum, and the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

He argues that, however controversial, he is reluctant to classify democratic votes themselves as “mistakes,” drawing a line between elite decisions and outcomes directly chosen by voters.

Why “worse than a crime” became the ultimate verdict

The phrase “worse than a crime; it was a blunder,” long associated with Talleyrand or Joseph Fouché, has been reused frequently in modern commentary to describe political miscalculations.

Analysts note that it captures moments when leaders manage to be both morally wrong and strategically self‑defeating. The Enghien execution remains the archetypal example: a ruthless act that also weakened Napoleon’s wider position.

Experts on misreading extremist leaders

Historians of interwar Germany highlight von Papen and his allies as a warning about trying to harness radical movements for short‑term advantage.

Educational summaries from public broadcasters emphasise that conservative elites believed they could “control Hitler and get him to do what they wanted,” a belief rapidly disproved once he used state power to dismantle checks, intimidate opponents, and centralise authority.

Defence analysts on the Nene–MiG‑15 export gamble

Defence and aviation writers have described Britain’s Nene engine exports as a serious strategic miscalculation. Commentaries note that British officials assumed domestic industry would stay ahead, underestimating Soviet engineering capabilities and determination.

Within a few years, MiG‑15s derived from British technology were matching or outperforming some Western aircraft, forcing costly responses and highlighting the dangers of underpricing long‑term security risks.

Recurring patterns: overconfidence and short-termism

Across these cases, familiar patterns emerge. Leaders overestimate their ability to manage events, underestimate opponents’ capacity to adapt, or focus heavily on short‑term political or economic gains.

The resulting damage—civil war, authoritarian consolidation, or military disadvantage—often becomes fully visible only years later. That time lag makes robust internal challenge and careful scenario planning especially important inside governments.

Why judging the “greatest” errors is inherently subjective

The ranking itself is openly subjective. Readers proposed many alternatives, from constitutional changes to devolution arrangements, revealing how personal background, national identity, and political values shape people’s views of what counts as a catastrophic blunder.

Rentoul presents the list as a starting point for debate rather than a definitive table, encouraging continued argument about consequences and responsibility.

Which current decision might join this list next?

The unresolved question is which contemporary decision will be viewed, decades from now, as a comparable turning point.

Choices on artificial intelligence, energy transitions, financial regulation, or great‑power rivalry all carry the potential for unintended consequences. History suggests that some actions taken today with confidence could later be remembered not merely as controversial, but as genuine political errors of the highest order.

Sources:

The Independent – “The Top 10: Greatest Political Errors of All Time” by John Rentoul

Encyclopaedia Britannica – “Ship Money” entry and coverage of the English Civil Wars

BBC Bitesize – “The Battle of Hastings – Norman Conquest” KS3 History overview

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – “Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Rise to Power, 1918–1933”

Standard aviation histories on the Rolls‑Royce Nene engine, the MiG‑15, and the Korean War air campaign