Switzerland has quietly built what some engineers call a second country beneath its mountains, a vast web of over 1,400 tunnels and more than 2,000 kilometers of hidden passages. This underground world carries most of the nation’s goods and people through the Alps, keeping heavy traffic off fragile mountain roads. The crown jewel is the 57‑kilometer Gotthard Base Tunnel, the longest railway tunnel on Earth.

Together, these tunnels allow freight trains to pass straight through the mountains while most travelers above enjoy quiet valleys and crystal lakes. What seems invisible from the surface is a cornerstone of Swiss precision and sustainability, a high‑tech system that keeps the country running efficiently while preserving the Alpine environment from noise, fumes, and endless truck convoys.

The Underground Maze of Switzerland

Beneath Switzerland’s valleys lies an astonishing network of interconnected tunnels, rail lines, road passages, water pipes, and service shafts stretching over 2,000 kilometers. Each tunnel blends into the landscape through modest entrances that hide the sheer scale of what lies beyond.

Together, these corridors rival the reach of world‑class metro systems like Tokyo’s or London’s, yet they remain mostly unseen. This subterranean infrastructure forms a kind of invisible metropolis designed for motion, logistics, and safety rather than living.

The Vote That Changed the Mountains

In 1994, Swiss voters made history by passing the Alpine Initiative, a bold public decision to protect mountain regions by reducing truck traffic and shifting long‑distance freight onto trains. Driven by widespread concern over air pollution and noisy highways, citizens demanded a clean alternative.

“The people wanted peace and protection for their valleys,” said Franz Weber, one of the initiative’s early activists. This single vote launched 30 years of planning, engineering, and construction that transformed Switzerland’s transport system from top to bottom.

The Backbone of the Underground Nation

At the heart of Switzerland’s underground revolution lies the New Rail Link through the Alps (NRLA), a mega‑project uniting the Lötschberg, Gotthard, and Ceneri Base Tunnels. Together, these form a flat, high‑speed transport corridor connecting northern and southern Europe beneath formidable mountain ranges.

Engineers refer to it as the spine of the underground nation. Each tunnel works in perfect sequence, allowing heavy trains to avoid steep climbs and sharp turns.

The Gotthard Base Tunnel: 57 Kilometers of Silence

Stretching 57 kilometers beneath solid Alpine rock, the Gotthard Base Tunnel is not only the longest railway tunnel in the world, it’s also one of the most extraordinary feats of engineering ever completed. Two parallel tubes connect northern and southern Switzerland, slashing travel times and making freight transport almost frictionless.

A passenger passing through experiences only 20 minutes of darkness before emerging into daylight again. For many, it’s an invisible wonder, a quiet link that changes everything but feels like nothing. Construction took 17 years and cost over $12 billion, involving more than 2,600 workers.

28 Million Tons of Rock

Building the Gotthard Base Tunnel meant carving through 28 million tons of rock, enough material to fill several skyscrapers or build multiple Great Pyramids of Giza. Giant tunnel‑boring machines cut through granite, gneiss, and limestone under extreme pressure and heat.

Most of the excavated rock was recycled into concrete or used to reshape the landscape into new wetlands and hills, a rare example of eco‑conscious reuse in large‑scale construction.

A Rail‑First Strategy for the Alps

Switzerland’s transport policy is guided by a simple idea: protect the Alps by moving freight traffic from roads to rail. This national strategy, developed in the 1990s, became the moral and technological foundation of NRLA. Instead of building more highways, Switzerland doubled down on electric trains and advanced tunnels.

According to the Federal Office of Transport, “Our constitution literally enshrines the aim to preserve the Alpine environment from transit damage.” That means trucks crossing the Alps pay high distance‑based fees, while rail operators get top‑tier infrastructure and government support.

Trains as Climate Weapons

Freight trains are remarkably efficient: they use about one‑fifth the energy of heavy trucks per tonne‑kilometer and emit roughly a quarter of the greenhouse gases. By shifting most of its Alpine freight traffic to rail, Switzerland effectively turned its tunnels into a silent climate project.

“Every kilometer of freight moved by rail instead of road is a win for the planet,” notes the International Transport Forum. Each of the country’s base tunnels can replace thousands of daily truck journeys, eliminating huge amounts of CO₂ and diesel soot.

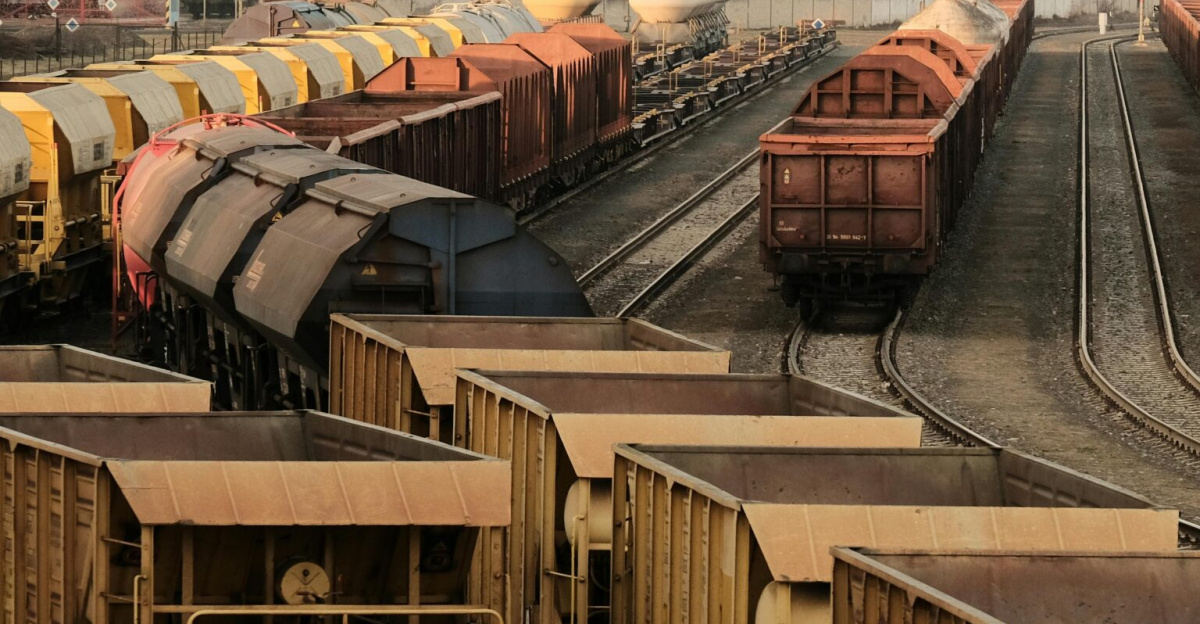

Bending the Freight Curve

Switzerland’s tunnels have turned a bold idea into measurable progress. Today, roughly 72–74% of all freight crossing the Swiss Alps moves by rail, far more than in neighboring countries like Italy and Austria, where most goods still travel by highway.

Every freight train that runs under the mountains replaces dozens of trucks that once rumbled over them. The Swiss Federal Audit Office describes this as “a rare case where environmental and economic interests align.” Logistics companies save time and fuel while mountain villages get cleaner air and quieter nights.

Fewer Trucks, Quieter Valleys

Before the tunnels took over, thousands of lorries crawled through narrow Alpine passes each day, filling the air with noise, fumes, and tension. Since the rail shift, life has changed dramatically for local residents.

Analysts say that without the NRLA system, at least 651,000 more trucks would have crossed the Alps in 2016, spewing about 0.7 million extra tons of CO₂ the following year. Children can play outside without the constant thunder of traffic, and tourism has flourished as the landscape feels natural again.

A Goal Still Out of Reach

Despite major progress, Switzerland hasn’t fully met its legal goal of limiting truck traffic below 650,000 crossings per year. Even today, the total hovers closer to 900,000, roughly 300,000 above target. “We’ve come far, but not far enough,” admitted a Swiss Federal Office of Transport specialist in 2019.

Critics argue that freight companies sometimes choose road routes through neighboring countries to avoid fees, dodging the system’s intent. Yet supporters remain optimistic. Continuous investment in rail automation and logistics hubs could close that gap within a decade.

The New Baseline Beneath the Mountains

By 2022, Switzerland’s balance between road and rail freight had stabilized, around 880,000 trucks per year compared with nearly 74% of goods now moved by train. This “74:26 ratio” has become the new normal, a strong but not yet ideal outcome. The Federal Statistical Office notes that these figures mark the lowest heavy‑vehicle counts in two decades.

The progress is significant, but room for improvement remains. Global trade continues to expand, and Switzerland’s north‑south routes still carry much of Europe’s freight flow.

Climate Adaptation in Solid Rock

Beyond emissions, Switzerland’s tunnels have become a hidden shield against climate chaos. Rising temperatures bring heavier rain, unstable slopes, and unpredictable snow seasons that can close surface routes for days. Underground, trains keep moving unaffected.

As extreme weather grows more common, this buried network doubles as disaster insurance, carrying people and goods through the Alps even when roads above are blocked. Engineers have learned to design tunnels not just for transport, but for safety, continuity, and climate defense.

How a Second Country Stayed Secret

For decades, the vast underground empire beneath Switzerland went largely unnoticed by the public. Most travelers only see a dark blur through their train window, unaware of the 2,000 kilometers of tunnels humming below. Construction happened deep inside mountains or secluded valleys, hidden from view.

Psychologically, people perceive it as brief darkness, nothing more. But beneath that illusion lies a continuous industrial heartbeat of light, motion, and precision. Workers lived for years in temporary camps near tunnel portals, quietly excavating a subterranean world that changed how an entire nation moves.

Life in Once‑Choked Mountain Villages

Before the Alpine Initiative, villages like Göschenen and Faido stood along some of Europe’s noisiest transit corridors. Endless truck columns rattled through, leaving diesel haze and danger on narrow roads. Since the tunnels opened, these same communities have transformed. Streets once dominated by haulers now host cyclists and market stalls.

The shift to rail didn’t just cut pollution, it restored the social fabric of communities long sacrificed to highway traffic. Local economies now thrive on tourism and small business instead of roadside fuel stops. The soundscape changed from roaring engines to cowbells and church bells.

A Project Measured in Decades, Not Quarters

Unlike most modern infrastructure projects that rush toward quarterly goals, Switzerland played the long game. From the first referendum in 1992 to the official opening of the Gotthard Base Tunnel in 2016, the NRLA unfolded over nearly 30 years.

That patience defines Swiss planning culture, slow, steady, precise, and deeply democratic. Each phase was approved by voters and executed with meticulous engineering oversight.

A Different Kind of Arms Race

Across much of the world, the solution to rising road congestion is simple: build more highways. Switzerland took the opposite path. Instead of widening roads, it dug deeper, literally. By investing billions in rail tunnels, it chose sustainability over short‑term convenience.

This quiet competition between modes mirrors a broader choice societies face everywhere: expansion or innovation. Switzerland bet on the latter, proving that reducing truck dependency doesn’t mean reducing economic mobility.

Why Other Nations Haven’t Copied Switzerland

If Switzerland’s underground success seems like a winning blueprint, why haven’t others followed? The answer lies in politics, geography, and culture. Switzerland is small, wealthy, and built on a tradition of direct democracy that lets citizens vote on massive public projects.

Other countries face greater fragmentation, multiple rail networks, short election cycles, and powerful trucking lobbies that oppose change. Geography also matters: few nations sit at such a vital crossroads between North and South Europe, where big freight flows justify such expense.

Lessons from the Underground Nation

Switzerland’s tunnel system offers lessons far beyond the Alps. It shows that climate progress doesn’t always come from flashy tech or global agreements, sometimes it’s built quietly, meter by meter.

The country applied practical tools: truck tolls based on mileage, strict emissions laws, reliable rail investment, and public accountability. “We didn’t wait for the world to agree. But the Swiss model also reveals limits: tunnels and trains alone can’t change freight behavior without firm rules and economic nudges. The success depends on balance, infrastructure plus smart policy.

The Revolution You Hardly Notice

For most passengers, traveling through the Alps feels effortless, a train glides into a tunnel, phones lose signal, coffee cups stay steady, and daylight returns 20 minutes later. But that peaceful moment hides a revolution beneath it: more than 2,000 kilometers of precision‑engineered passageways, built to reduce emissions, noise, and stress on the planet.

Each ride through the Gotthard Base Tunnel is a journey through decades of human ingenuity, one that silently replaces thousands of trucks and millions of liters of diesel. Switzerland has proven that the future of transport doesn’t always roar, sometimes it hums in darkness, deep below the mountains, where a nation quietly found a greener way forward.

Sources:

Ecoticias, Switzerland has excavated a “second country” beneath the Alps, 16 January 2026

Times of India, Switzerland has built an underground world so vast that it competes with metro systems, 14 January 2026

Wikipedia, Gotthard Base Tunnel, last updated (page active since) 29 May 2004

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO), Transalpine goods transport, (current online edition, accessed 2026), no specific day given

About Switzerland (Federal Administration), Freight transport, 25 September 2025