A rhinoceros skeleton buried beneath Canada’s High Arctic for 23 million years has emerged as the northernmost member of its family ever documented, fundamentally reshaping understanding of ancient polar ecosystems and mammal migration patterns. Recovered from the Haughton Crater on Devon Island, Nunavut, the fossil represents roughly 75 percent of a complete skeleton—an extraordinary level of preservation that allows scientists to reconstruct the animal’s anatomy, behavior, and environment with unusual precision.

The species, formally named Epiaceratherium itjilik, challenges long-held assumptions about Arctic climate history and reveals that regions now locked in permafrost once supported diverse, temperate forests inhabited by large herbivores. Published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, the discovery extends beyond paleontology, offering insights into ancient climate dynamics, mammal evolution, and intercontinental migration during the Early Miocene epoch.

A Crater That Preserves Deep Time

Haughton Crater, a 23-kilometer-wide impact structure formed approximately 31 to 32 million years ago, provided the geological conditions necessary for exceptional fossil preservation. After the asteroid collision, the crater filled with water during the Early Miocene, creating a lake environment where fine-grained sediments accumulated on the bottom. Low-oxygen conditions in these lake deposits slowed decomposition, allowing the rhinoceros remains to undergo only partial mineralization while retaining three-dimensional bone structure.

Permafrost processes later brought fossils closer to the surface through repeated freeze-thaw cycles, a phenomenon known as cryoturbation. This natural exposure enables researchers to discover new specimens each field season without excavation. The combination of rapid burial, stable cold temperatures, and protective sediment layers made the crater an archive of life from a radically different Arctic.

Forests Where Ice Now Rules

The presence of a browsing rhinoceros confirms that Devon Island once hosted a temperate, forested environment fundamentally unlike today’s polar desert. During the Early Miocene, the region supported vegetation comparable to modern southern Ontario or northern New York, with trees including birch, larch, and pine. Winters brought cold and darkness, but summers were warm enough to sustain complex ecosystems with diverse plant and animal communities.

Epiaceratherium itjilik was a small, hornless species roughly the size of a muskox—far smaller than modern African or Asian rhinoceroses. Its dental structure indicates it fed on leaves and soft vegetation rather than grasses, consistent with a wooded habitat. The animal shared its environment with other species, including Puijila darwini, an otter-like mammal representing an early stage in seal evolution. Together, these fossils document a lost world where terrestrial herbivores and semi-aquatic carnivores coexisted in Arctic forests.

The species name reflects both scientific classification and cultural collaboration. “Itjilik,” meaning “frosty” in Inuktitut, was chosen in consultation with Jarloo Kiguktak, a former mayor of Grise Fiord and an Elder who participated in multiple research expeditions to the crater. This approach honors Indigenous language and recognizes that the fossil was found on Inuit homelands.

Proteins That Outlast DNA

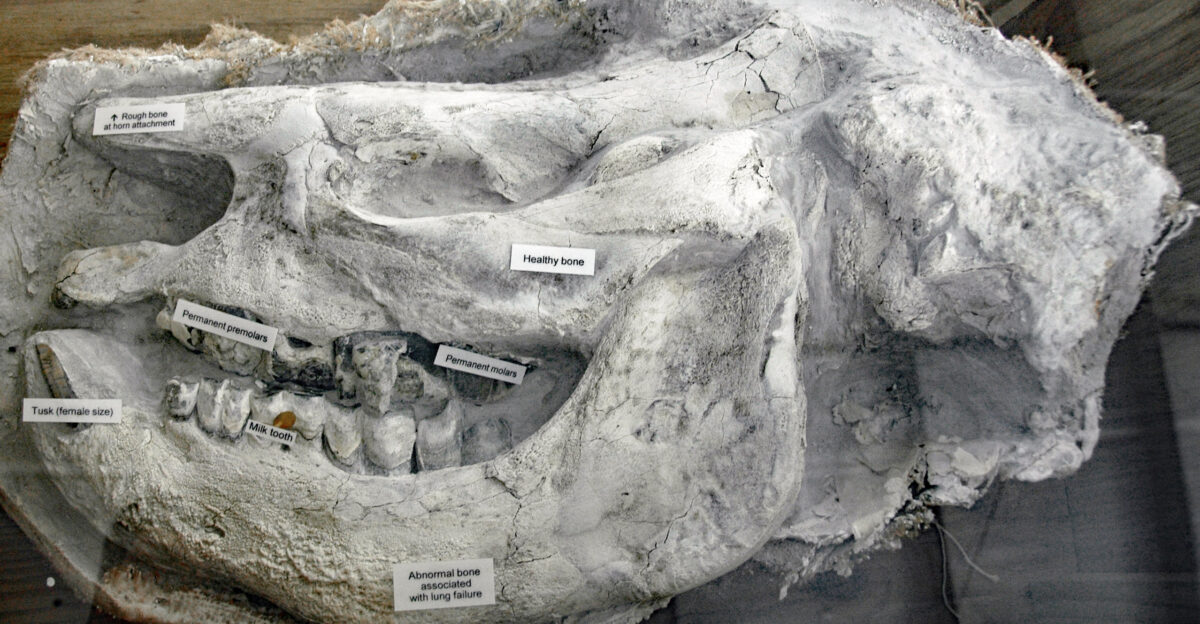

In a separate but related breakthrough, scientists successfully extracted and sequenced enamel proteins from a closely related Early Miocene rhinoceros tooth from the same region, dating between 21 and 24 million years ago. These proteins represent the oldest mammalian proteome ever recovered—ten times older than any ancient DNA sample. Unlike DNA, which degrades rapidly, tooth enamel proteins can survive geological timescales under cold, stable conditions.

The protein sequences allowed researchers to estimate when Arctic rhinos diverged from other rhinocerotid lineages, placing the split between approximately 41 and 25 million years ago during the Middle Eocene-Oligocene. This molecular evidence also suggests a more recent divergence between the two main rhinoceros subfamilies, Elasmotheriinae and Rhinocerotinae, occurring around 34 to 22 million years ago. These findings align with anatomical evidence and demonstrate that paleoproteomics can provide phylogenetic information far beyond the reach of traditional DNA analysis.

Rewriting Migration and Evolutionary History

Epiaceratherium itjilik belongs to a genus of small, hornless rhinoceroses previously known only from Europe. Its presence in the Canadian High Arctic raises questions about how it crossed from Eurasia to North America. Scientists had believed that land connections between the continents disappeared approximately 10 million years before this species existed. The discovery provides evidence that animals may have continued crossing via seasonal ice bridges or intermittent land routes during the Early Miocene, extending the timeline for intercontinental mammal exchange.

More than 50 rhinoceros species are recognized in the fossil record, with only five surviving today. Epiaceratherium itjilik represents a period of evolutionary experimentation when rhinoceroses occupied diverse habitats across multiple continents. As climate shifted over millions of years, species like the Arctic rhino vanished through natural environmental transitions—long before human influence. The fossil demonstrates both the adaptability of early rhinoceroses and the inevitability of extinction when habitats disappear. As permafrost continues to thaw and Arctic landscapes erode, paleontologists anticipate additional discoveries that will further illuminate the deep history of polar ecosystems and the species that once thrived there.

Sources:

“Discovery of an extinct rhino from Canada’s High Arctic” – Canadian Museum of Nature (news release)

“Rhinos Lived in High Arctic 23 Million Years Ago” – Sci.News

“Ancient rhino teeth unlock 20-million-year-old secrets in Canada” – ArcticToday

“Rhino discovery shows Arctic ‘big centre’ for mammal evolution, researchers say” – Nunatsiaq News

“Hornless rhino roamed Canadian High Arctic 23 million years ago” – Reuters (via multiple outlets)

“Scientists Discover a 23-Million-Year-Old ‘Arctic Rhino’ in Canada” – SciTechDaily